Before the International Style (modernism) in architecture, our ancestors knew how to adapt the room heights according to the climate, achieving maximum effect (comfort) for the least effort (energy). Today we trust in the grid and so build 8-9 ft rooms from Bermuda to Reykjavik.

In warm climates you need ample ceiling height, as hot air rises the difference in temperature at floor level and ceiling level in a tall room can be as much as 4 degrees c all other things being equal. Here, a comfortable looking gentleman in an 1817 room in Rome, height, ca 5m.

In Brazil, homes were traditionally built with a minimum of 3m ceilings. In the 20th c. an effort was made to conserve building material, and so rooms shrank in size, 20cm each decade, until the modern 2.6m. The only problem was, temperatures rose 1 degree c per 20cm reduction!

As humans are comfortable only in very narrow temperature ranges, small changes make a huge difference. Even the poorer had tall ceilings and could live with comparative comfort, not so much today, and at a huge expenditure in money, time, (fossil fuel) energy, materials.

Conversely, in colder climates, lower ceilings meant higher temperatures. Here are log houses from Russia and Sweden. The efficiently constructed fireplace created an interior draught that sucked fresh air in and expelled smoke, dust. Fans or mechanical ventilation not needed.

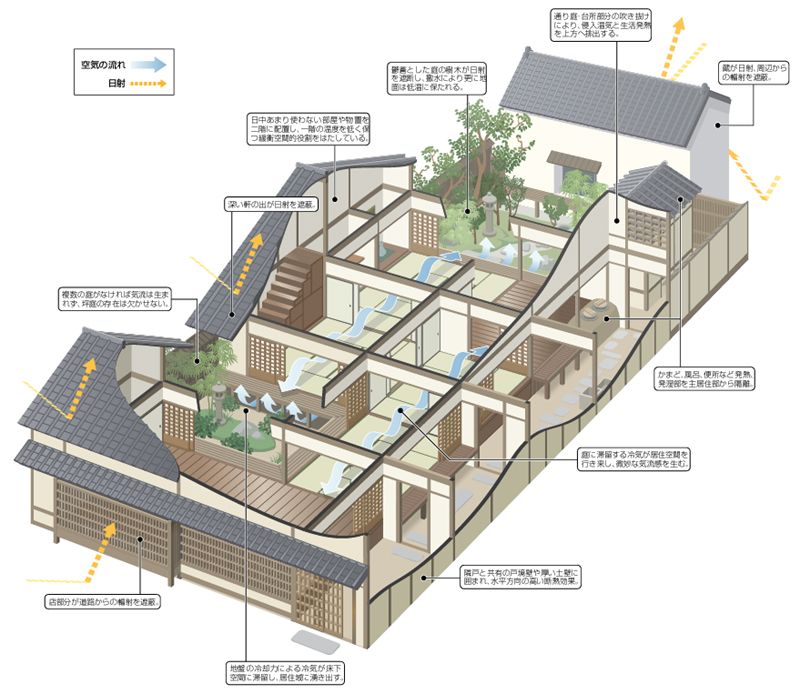

In Japan, with hot summers and relatively cold winters, a different technique was called for. Wooden houses allowed for perfect fine tunings of openings depending on exact climate and orientation. Thsi traditional room built to maximize airflow, livable in summers without AC.

By building with nature and climate instead or regardless of it, by adapting our waking hours to the rhythm of the sun we can achieve remarkable levels of comfort—even superior—compared to what we have today in our modern homes built to international, industrial standards.

So far I have mentioned how room height affects temperature, but indoor comfort is also dependent on humidity. Let's see what role materials play in making your room naturally more or less comfortable to be in. Stay to see the grande finale tying all these methods together.

Modern homes are full of materials that have no effect on air humidity: plastics, particle board furniture, PVC wallpaper, vinyl flooring, whereas traditional homes made of natural materials (hygroscopic) such as wood, earth, straw, brick, that helped regulate indoor humidity.

Using wood for your interiors will not only create better indoor air (no off-gassing of formaldehyde, common with particle boards, paints, drapes etc.) it will also help regulate indoor humidity, buffering moisture when air humidity is high and releasing moisture when it is low.

Research shows that wooden interiors can cut the highs and the lows of the humidity cycles by 40-60%, creating a more stable and comfortable indoor climate throughout the day. You can add mud/earth for an even higher effect and comfort. Virtually free, unlike modern dry wall.

Earth plasters, solid rammed earth walls, or earth and mud infill function as a great buffer material for both moisture and heat, research has shown it to have a hugely beneficial impact on the perceived comfort of indoor climates, making it an ideal choice for hot humid summers.

Let's go to Japan. Traditionally, the Japanese urban home (the machiya) combined all of these materials with a construction fine tuned to encourage cross breezes and interior air flow. Humidity was regulated by using wood, woven grass mat floors, earth plaster walls, etc.

During the hot and humid summers of Japan, these houses regulated indoor temperature and humidity—without using any form of mechanical or electrical devices—to a remarkable degree. But the best is yet to come: they knew how to command up a breeze!

The machiya were narrow townhouses with a short front to a paved street. Towns were crowded and densely populated. A machiya was built with a narrow corridor—the tooriniwa—connecting the street with the entire length of the house all the way through to the garden at the back.

The tooriniwa had generous skylights, tenmado that brought natural light in all through the deep house. It went from bare earth (humidity) to the roof (air flow, tall ceilings) allowing the wind to reach even the deepest rooms of the house. Indoor climate control built as a room.

On hot and humid windless days the Japanese had one final trick: uchimizu (打ち水), the scattering of water on the pavement in front of the house (we moderns have a technical term for it: evaporative cooling).

As cool water hits hot pavement, the air temperature can drop up to 13 degrees c in a few seconds, this creates a minute change in the local air pressure, pushing the cooler air into the house, forcing the stale hotter inside air to rise and escape: a breeze. Almost like magic.

It is possible to build far more energy efficiently and comfortable using traditional techniques and materials. Homes can be built for the fraction of the cost of our modern houses, employing locals using only, renewable, local materials: with good care they can last centuries.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh