A few thoughts about the Fourth Flood… what we’re seeing right now isn’t anything like Harvey or Allison; its not even Tax Day or Memorial Day. But it’s still showing us some really issues we need to deal with.

Right now, the @hcfcd website (with its live stream gauges and really useful new live inundation feature) is showing all the bayous within their banks. harriscountyfws.org

The @RiceUniversity SSPEED Center’s Flood Alert System on Braes Bayou is predicting that flows past the Med Center will peak around 2:00 pm. (We need one of these predictive systems on every bayou!)

…but my Twitter stream is full of pictures of streets underwater and people are worried about their houses. This isn’t bayou flooding; it’s localized flooding, from water that hasn’t made its way to the bayou. Its one of our biggest flooding problems.

There’s been some really progress here — the City of Houston has been upgrading storm sewers, and neighborhoods built after 1980s infrastructure regulations do a lot better than older neighborhoods — but there’s a lot more we as a region could do.

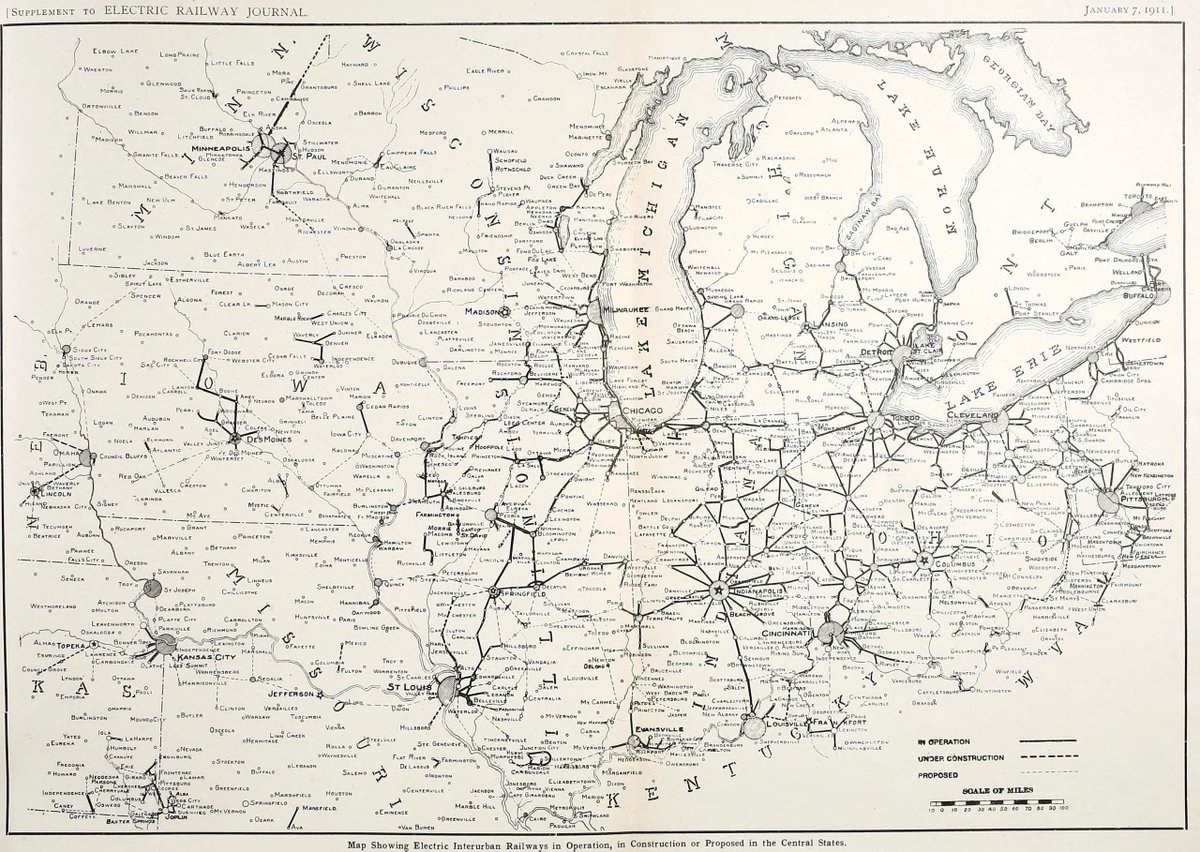

For one thing, our mapped floodplains are not really relevant for this flooding. Here’s the Memorial City area. Left: FEMA floodplains. Right: modeled local flooding. Look how much the floodplains don’t include! But we don’t have this analysis for most neighborhoods.

Also, other than anecdotal information, we don’t have a really good understanding of what happens to our roadway system in a storm like this. What streets are impassable? What neighborhoods are cut off, and what routes are remain open?

First responders would be able to do their jobs much better if they had this information live. Residents would be less likely to be stranded. And we might identify streets or bridges that could be reconstructed at a higher elevation to keep crucial connections open.

There’s also a lot more we could do to reduce flooding the next time this happens. There are surely small scale drainage projects all over the region that could help, in addition to (and complementary to) the large scale bayou-focused projects.

Better maintenance of ditches and storm sewers would help, too, along with ways to keep debris out of them. (I’ve heard from places like Independence Heights that flooding is worse on trash days since trash bags and cans block the ditches.)

There’s also a whole set of lot-by-lot strategies — grading to move water away from and around houses, front yards depressed to act as really small scale detention — that could do a lot of good in those pre-1980s neighborhoods.

Those tools haven’t been fully analyzed or understood, but if they were, and permitting/financial assistance programs were in place to make it easy for homeowners to implement them, it could prevent flooding that neither large scale projects or new building regulations can.

If we take the things the region is already doing like bayou projects and buyouts and building regulations (all important, and effective) and add more strategies, we can significantly reduce the impact of flooding, not just in big events but in smaller ones like today.

… it feels like we’re at a moment where the county and the city and everyone involved are open to that, and the public will support it. Houston can really innovate here — and make days like today a bit less scary.

More information from the Greater Houston Flood Mitigation Consortium (a really amazing group of local and statewide experts which I’m project manager for): houstonconsortium.com/p/report

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh