The reason we can't build cheap rail anymore is because we always want to start with the perfect, latest, cleverest and shiniest technology. Far more complex and far more expensive than what any town on Earth can afford today. The solution is to build only the most basic system.

Start low tech, on existing streets, with horse drawn carriages if necessary. Build several small towns (centers in the city) round every spot where you want the railway to stop. Build ridership at the same time you build the railway, if at all possible.

Once you have the line down and people see that the railway company is committed to operations, the city will adapt to it: people who work along the line will want to live there. People who live along the line will want to work there.

Starting low tech means not investing in expensive to maintain, complex technical systems prone to breaking down: slow running trains on narrow streets means that it will make the city fractal: creating many stops, many points of interactions. It can run on streets or alleys.

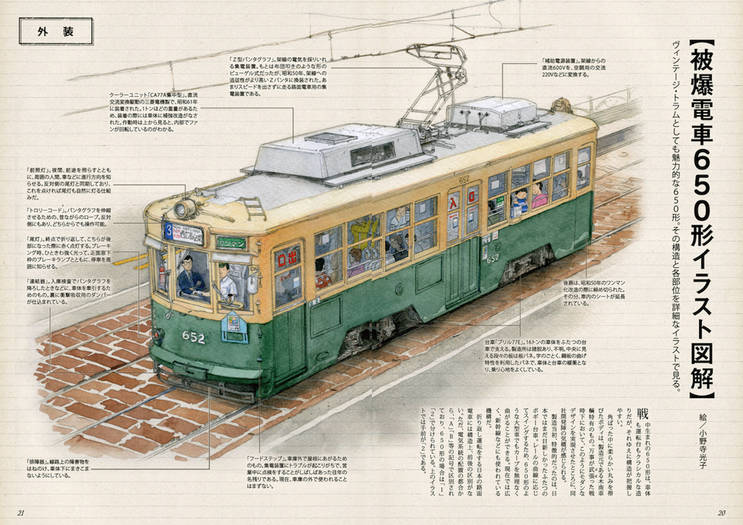

Low tech means incredibly robust systems: in 1945, within three days of being hit point blank by a nuclear bomb Hiroshima trams were cleaned up and put back into service, staffed by high school girls. Feel free to compare with your modern system.

If we must have public transport (or any kind of transport above walking actually: I'd rather we did not!), let it be small. Let it be slow. Let it be anti-fragile. Let it be owned and managed by the community it works in. Let it be so adaptable that it can fit in everywhere.

You can fit a low tech system into a complex modern system, but you can never do the opposite. You can even go steam train in your city center should you wish, but you can't ever properly integrate a bullet train in your cosy town center by the sea.

Low tech means people scaled. People will feel that they can relate to a locally adapted will integrated system. Even if it is just a scraggly line run down the main street for a mile or two. You'd find it hard to not have your local tram turn into a mascot for local tourism.

You can scale a small low tech system: just put in an extra stop where needed. Move an old stop 200m down the street if necessary. Add a line if one gets congested or make a new one altogether. Put in more cars or take some away. If your town grows taller your trams can grow too.

Bigger cities have plenty of parks that are largely underutilized and often neglected. They make great scenic shortcuts for small scaled rail systems, creating new routes through central city parks while preserving a maximum of green space. Remember, rail is space friendl(ier).

Human scaled rails need human scaled stations and stops creating a great opportunity for charming tiny vernacular buildings, perfect for local carpenters, steering money away from large construction companies and environmentally unfriendly constructions draining local budgets.

Local businesses loves local railways. Make sure there are plenty of tiny spots, small squares and tiny buildings around the station and stops: businesses will flock to it. The synergy effect is obvious, thriving trains creating thriving shops, leading to a bigger ridership etc.

Like it or not, but we humans are social animals. We thrive when we do good things together and we ought to do more things together. Human scaled railways bring people together (unlike cars!) and even if that was the only benefit, trains would be worthwhile. (ht: @DrJoshMadden)

@DrJoshMadden Small local railways can also access places that large state run or high tech systems can't or don't want to go. Like the famous Ascensor da Glória (Elevador da Glória), a funicular/tram cross-cross over system in Lisbon that goes up some very steep streets.

Usually at this point someone asks about how compatible these old trams were with disabled and users with wheelchairs. We know because we still employ humans to provide services far more user friendly than any mechanical system.

A human scaled system relies on human interactions, employing locals as ticket inspectors (no need to invest in ticket machines) and conductors. And see what smart uniforms we can provide them with. We fool ourselves when we automate the most valuable jobs in our communities.

"But what about buses?" Well buses are better than nothing but not as good as rail. Buses also require a street network and then you get cars and cars are poison. Rail is also always more logically laid out and feels far more reliable than a bus route: citylab.com/transportation…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh