We are often told that that the raids by chOzha emperor rAjendra I on the shrIvijaya-s were due to the latter's "interference with trade". Unfortunately, the exact nature of interference has been, for long, elusive to us.

It has been elusive for even the erudite nIlakaNTha shAstri as we had always relied on Indian documents. So what was this “interference”? An interesting (& rather hilarious) answer is found in the work of Tansen Sen & Noboru Karashima.

In getting the historical context, we have to appreciate the role of shrIvijaya as a leading entrepot state in the Indo-Chinese trading world; serving as a transit point for ships sailing from cIna coasts to various cities in the Indosphere-in Southeastern Asia & India.

This role of shrIvijaya as an entrepot state par excellence can be traced to the last decades of the seventh century. We know this from the accounts of bauddha monks such as the cIna Yijing, vajrabodhi (from kA~nci) & the renowned amoghavajra of bAhlikadesha (Uzbekistan).

Yijing left cInadesha on a ship bound for shrIvijaya where he spent 6 months studying saMskRta & would hop between various S.E.Asian cities before he finally got a chance to leave for bhArata & would reach Nalanda, Bihar where he spent a good 17 years. iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/nsc…

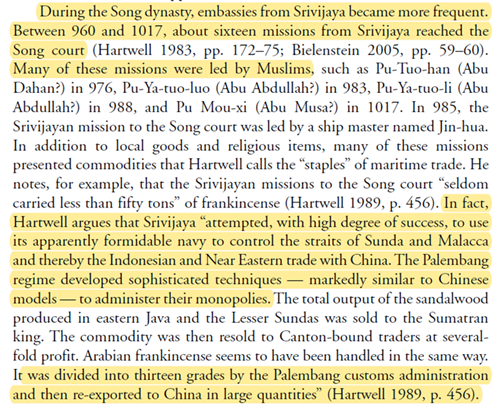

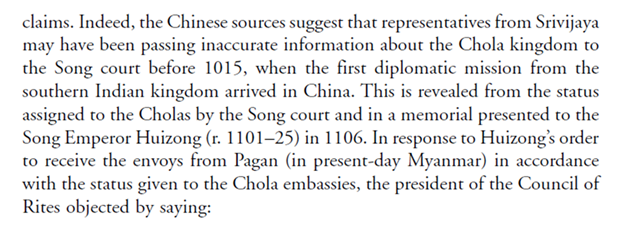

Coming back to shrIvijaya, Tansen Sen points out that diplomatic missions from shrIvijaya to cInadesha became rather frequent during the Song dynasty. There were 16 such missions in the period between 960 & 1017 CE. Sen notes the shrIvijaya ambition to monopolize trade.

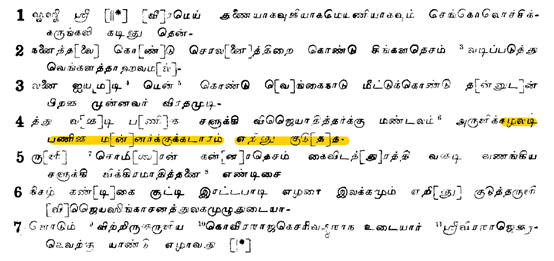

Now, before we move on, let us sort out a few key dates here. The chOzhas sent their very 1st mission to cInadesha in 1015. rAjendra-I launched two raids in the years 1017 & 1025 on shrIvijaya. But in 1068, vIrarAjendra invaded kadAram (shrIvijaya) before reinstating its ruler!

This is rather puzzling. Why would he send the chOzha military across the seas & then immediately reinstate the king? nIlakaNTha shAstri reads the inscription (SII, Vol.3, Inscription No.84) as indicating that vIrarAjendra reclaimed kadAram for the abdicated shrIvijayan ruler.

Whether this was done to favor the shrIvijaya king or was it hostile in intent like the raids of 1017 & 1025, I am not too sure. But in any case, it confirms that shrIvijaya was a dependent protectorate of the chOzhas by & in 1068.

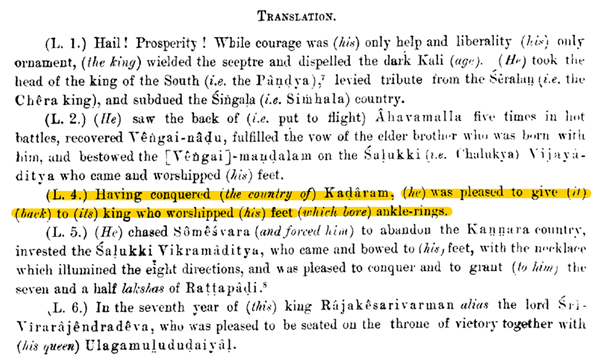

We now look to the Songshi, the official historical account of the Song dynasty of the cIna-s, one of 25 such documents chronicling the histories of various dynasties. It is funny that we should get our motive behind the 1017/1025 raids from a letter in the Songshi dated 1106.

It is a letter (a “memo” of sorts) to the Song Emperor Huizong, expressing an objection by a Minister to the royal order to receive diplomats from the Pagan Kingdom (蒲甘—púgān, Myanmar) with same honors as chOzha (注輦—zhùniǎn) embassies. chinesenotes.com/songshi/songsh…

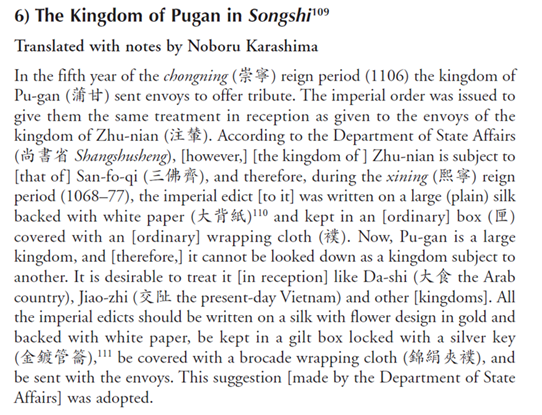

In the letter, the zhùniǎn (chOzha) are described as a vassal of the Sānfóqí (三佛齊—shrIvijaya)!! The Chinese had thought in 1106 that the mighty chOzhas were the vassals of the shrIvijayas despite the fact that this of course is complete nonsense!! What’s going on?!

Sen surmises that for a century or even a little more, the shrIvijayans had been using their status as the primary entrepot/transit state to pass false data to the Song officials that the chOzhas were their vassals & had even done the same to siMhaladesha!

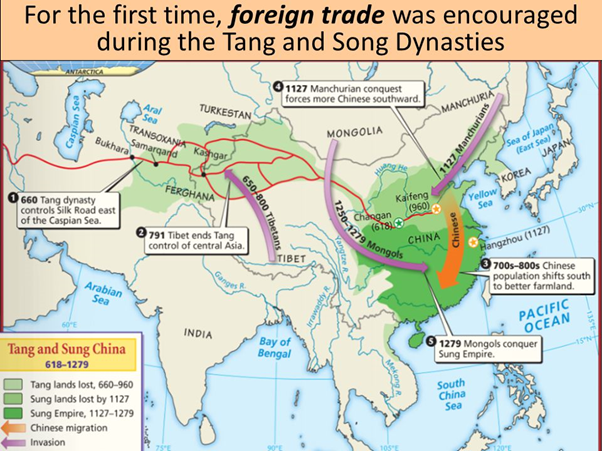

To understand how something ludicrous could happen, we have to understand that the Song world was rather distant from the chOzha world & communications were not quite like what they were today. So, what were the consequences of such false intelligence? slideplayer.com/slide/5815859/…

Sen explains that chOzha traders lost preferential access to Song markets as the cInas perceived them as a militarily weak dependency, having been “tricked” by the shrIvijayans into believing so. & even after the raids, the cInas continued (till 1106 as seen above) believing it!

However, the raids did wield tremendous damage to the shrIvijayans at that time & post-raids, we are informed that they did not manage to send embassies to cIna (their trading fleet & economy being rather wrecked).

The geopolitical lessons from this rather funny story may seem to be irrelevant in light of how communications & intelligence works today. But it is perhaps interesting to see how states/economies/trade worked once & how the cInas had always responded when they smell weakness.

@threadreaderapp Unroll

From chapter 3, "THE MILITARY CAMPAIGNS OF RAJENDRA CHOLA AND THE

CHOLA-SRIVIJAYA-CHINA TRIANGLE" by Tansen Sen in "Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia" (2009).

CHOLA-SRIVIJAYA-CHINA TRIANGLE" by Tansen Sen in "Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia" (2009).

Please also see Appendix II of the above-mentioned book, "Chinese Texts Describing or Referring to the Chola Kingdom as Zhu-nian" by Noboru Karashima & Tansen Sen.

Some lessons to keep in mind:

1. 1st-mover advantage in building relationships; shrIvijaya's headstart in setting the narrative (as blatantly false & BS it was)++

1. 1st-mover advantage in building relationships; shrIvijaya's headstart in setting the narrative (as blatantly false & BS it was)++

2. Ought to have established occasional high-level contact with the cInas, which may have resulted in clarity instead of sending chOzha traders with little royal official presence.++

2'Cont'd: This was definitely one of those situations where the chOzhas should have sensed disproportionate influence of shrIvijayans & "gotten rid of the middleman" sooner. Allowing an intermediary to set the discourse/relationships for that long is a recipe for disaster.++

3. Failing to be fully brutal by not annihilating the shrIvijayas for what they tried to pull; even "magnanimously giving back" the kingdom to an abdicated shrIvijayan ruler decades after these episodes.

4. Of course there was some efforts by rAjendra at proper diplomatic contact in 1020, just 5 years before the 2nd raid, as already noted here:

However, that had failed since the lead envoy died (suspicious much??).

However, that had failed since the lead envoy died (suspicious much??).

https://x.com/GhorAngirasa/status/1099670660547149825

5. The raids did achieve a 10-year disruption of shrIvijayan missions to cInadesha, but after this long absence, the shrIvijayans were able to convince the cInas with little effort that the chOzhas were their vassals all the way till 1106, despite relying on chOzha mercy in 1068!

6. While the shrIvijayans were persistent in their being pests to the chOzhas, the chOzhas were not persistent or brutal enough in their response.

7. Finally, it is interesting (although I lack data to conclude anything of significance) to note Muslim role in the shrIvijayan missions to China! (Although shrIvijaya was largely Hindu-bauddha, Islam seems to have penetrated the high state offices.

//End

//End

https://x.com/GhorAngirasa/status/1099670630545281024

@threader_app Compile

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh