The traditional way of showing that your shop is open for business in Japan is by hanging a cloth curtain, a noren (暖簾 or のれん), in front of it, a tradition dating back at least to the 8th century. Practical, economical, and beautiful. Let's have a look.

In an era before printed advertising, plastic paints and expensive showy signage, the noren was an efficient way of shielding the entrance to your shop from the dusty street, cold winter winds or harsh summer sun. The earliest and most traditional noren were made of linen.

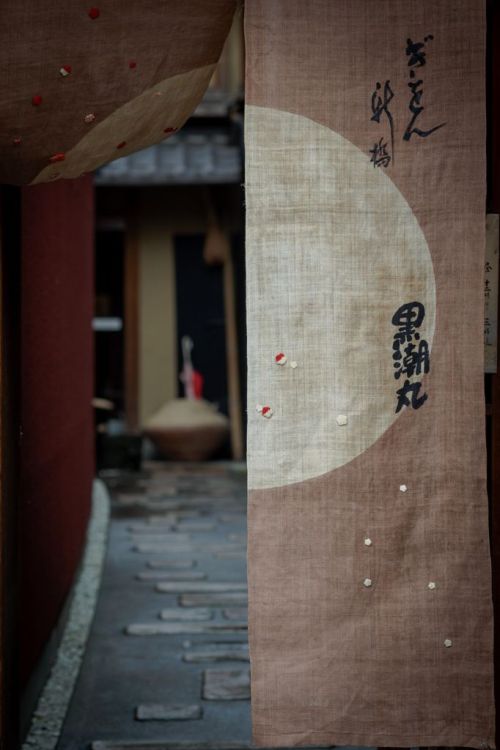

At first they were plain, or with simple shapes or patterns, but as literacy really took of in the 17th century people could write the name of the master, the logo of their business, or any character that symbolized their craft or wares.

Until the 20th century, the color of the noren signaled the business of the store. White was color of sugar, so it became the standard noren color for sweet shops, confectionaries, and also apothecaries (as sugar was a standard ingredient in many bitter medicines, then as now).

Brown and yellow was the color of tobacco sellers, and also the color of tea houses as the tea drunk by ordinary people was brown, but as more people took to green tea in the 20th century the color for tea shops has now become green instead of brown.

Purple used to be very rare, not only was it a difficult color to produce, but it was also used to enforce repayment of loans: shops who borrowed money had to put out a purple noren, until they payed back. Today we see it sometimes, for example in this sake museum in Kyoto.

However the most famous color is the navy blue, or indigo noren. Traditionally used by kimono stores, liquor stores, or soba, ramen, udon restaurants.

Indigo was also the preferred color of sushi restaurants, as the natural plant dye to make the color had an insect repellant ingredient, and the indigo blue came to represent freshness, free from insects.

Even the color of the image or writing in the noren had symbolic meaning: red was always avoided, as red writing in accounting meant deficit. Hence, writing would usually be in black, or sometimes white. This noren also has the kamon, or family/clan crest inspired logo.

Nowadays many noren are made of cotton, which is a bit heavier material than the traditional linen. But still there is a Japanese idiom, 暖簾に腕押し, "push against the noren", similar in meaning to the English "flogging a dead horse", as an action that is a waste of effort.

An iconic use of noren is the sento (public bath houses) and onsen (hot spring baths), that uses the symbol for hot water, either 湯 or ゆ. Few modern bathhouses dispense of the noren to this day!

Today noren usually disregards the traditional colors, and is more used to express the logo or graphic identity or brand of the shop, even when their logo itself is highly traditional, as this kamon, used by a business in Kyoto.

Noren can also be used indoors, as temporary doors or to divide large rooms into smaller sections, or to provide stage backgrounds for performances or entertainments in shops. In Japanese museums it is common to see them used as information boards.

Foreign brand stores that want to blend in with the traditional Japanese streetscape has really taken to the traditional noren, even though they prioritize branding over choice of colors. Here are some foreign brands in Kyoto: Hermes, Leica, Starbucks.

The traditional noren made of linen could be easily manufactured at home, from a handful of seeds and a free patch in the family garden, a truly sustainable way of advertising your business.

Noren is also an effective means to preserve ancient crafts: in Kyoto for example, craftsmen are kept in business and by a government program that offers financial support for businesses that use their products for their noren, supporting weavers, dyers, artists, calligraphers.

For absolute noren purists there is the nawanoren, of woven hemp ropes, probably the oldest form of noren dating back over 1500 years. Very stylish, but it demands a certain level of confidence in the customer to enter a shop like this.

Another specialist noren is the hanayomenoren, which was hung in front of the family altar when a daughter of the bride was married. It would only be used during a week, and then presented to the bride in her new family. A local tradition, very rare today.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh