I'd like to share some reflections on the death of a patient. I’ve thought about her a lot.

She gave me explicit consent to tweet the details of her case, about four hours before she died. Her hope was that someone might benefit from her experience.

/1

She gave me explicit consent to tweet the details of her case, about four hours before she died. Her hope was that someone might benefit from her experience.

/1

She came to hospital as octogenarians often do: with generalized weakness, falls, poor oral intake, fever, hypotension.

Her WBC was 17,000. Blood cultures grew E. coli.

Sepsis. Fixable enough.

/2

Her WBC was 17,000. Blood cultures grew E. coli.

Sepsis. Fixable enough.

/2

But she also complained of pain in her groin and thigh. It was new, progressive and debilitating.

Even moving around in her hospital bed was agonizing.

/3

Even moving around in her hospital bed was agonizing.

/3

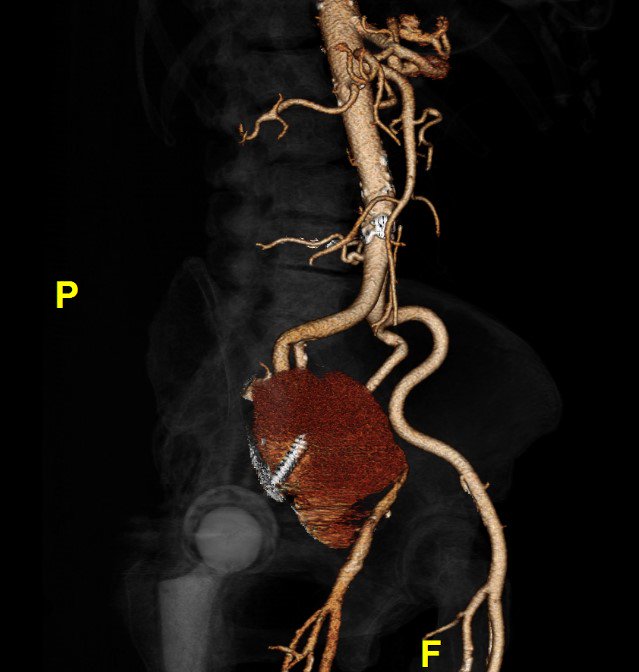

A month earlier, she’d been found to have a large pseudoaneurysm arising from her external iliac artery.

(And yes, that’s a screw from a previous hip replacement traversing it.)

She underwent stenting and returned home.

/4

(And yes, that’s a screw from a previous hip replacement traversing it.)

She underwent stenting and returned home.

/4

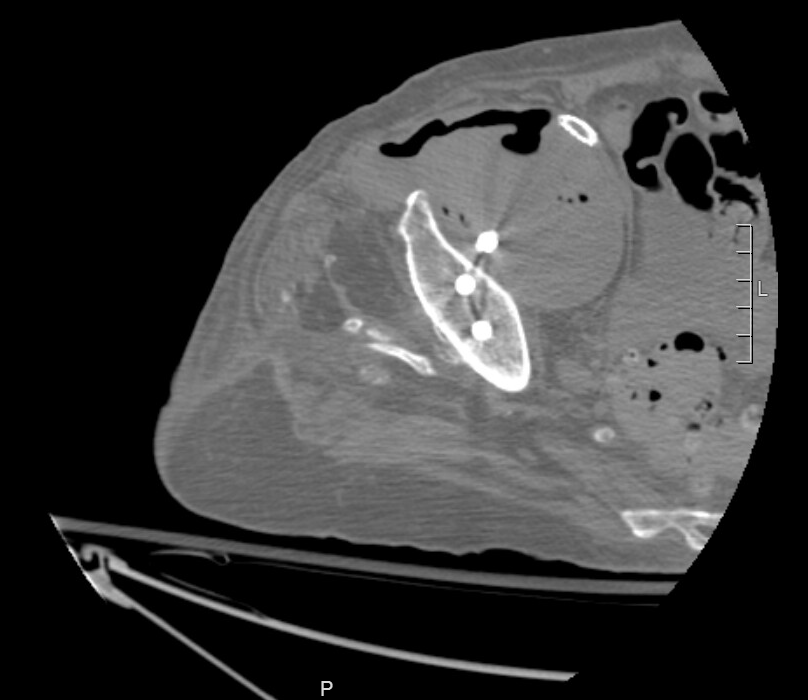

Because she was septic and in pain, we scanned her again. The new CT showed extensive gas within the pseudoaneurysm.

It was now infected, and that was a big problem.

/5

It was now infected, and that was a big problem.

/5

We continued antibiotics. She improved. We got her pain under reasonable control with hydromorphone and various other meds.

But then came the big question: “Now what?”

/6

But then came the big question: “Now what?”

/6

She wanted no more surgery. Her mind was now sharp, and she was clear about that.

But antibiotics alone weren’t going to cure the infection; they would only suppress it.

The best option, we suggested, would be antibiotics for the rest of her life.

/7

But antibiotics alone weren’t going to cure the infection; they would only suppress it.

The best option, we suggested, would be antibiotics for the rest of her life.

/7

We discussed this option at length. She didn’t want it either. She explained why.

Pain was one reason. Meds helped a little, as long as she didn’t move around much. But our drug options were limited, and pain was going to be a persistent problem.

/8

Pain was one reason. Meds helped a little, as long as she didn’t move around much. But our drug options were limited, and pain was going to be a persistent problem.

/8

Her even greater concern, looking forward, was quality of life.

Over the preceding months, she’d lost her mobility and independence. She wasn’t going to get them back and she knew it.

/9

Over the preceding months, she’d lost her mobility and independence. She wasn’t going to get them back and she knew it.

/9

She foresaw being confined to her apartment, in pain, struggling with her walker.

No more walks outside. No trips to the grocery store. No playing bridge with her friends, as she had done for years.

She wasn’t interested in living like that.

/10

No more walks outside. No trips to the grocery store. No playing bridge with her friends, as she had done for years.

She wasn’t interested in living like that.

/10

We discussed palliative care: stopping antibiotics, increasing her pain meds, and keeping her comfortable while the infection took its course. Her family would keep vigil at her bedside for as long as it took.

She wasn’t interested in dying like that.

/11

She wasn’t interested in dying like that.

/11

She knew she was nearing the end of her life. What she wanted, she told us, was for it to end peacefully, with her mind still sharp, and her family and friends present. She wanted medical assistance in dying (MAiD).

/12

/12

We held a family meeting. Relatives came from near and far.

They were unconditionally supportive. As it turned out, she’d discussed the prospect of MAiD, were it ever to become an option, several times in recent years.

So that became the plan.

/13

They were unconditionally supportive. As it turned out, she’d discussed the prospect of MAiD, were it ever to become an option, several times in recent years.

So that became the plan.

/13

I saw her every day after that. Managed her pain. Listened to her stories. Learned about family members who’d died, and whose deaths had influenced her decision now.

Never once did she reconsider. I grew very fond of her, especially her wit and clear-eyed stoicism.

/14

Never once did she reconsider. I grew very fond of her, especially her wit and clear-eyed stoicism.

/14

After the requisite waiting period and medical assessments, the day had come.

I visited her at 7:30 that morning. She was alone but upbeat, eating Cheerios and toast from her tray.

(I still regret that this was her last meal. Wish I’d brought her a fresh bagel with lox.)

/15

I visited her at 7:30 that morning. She was alone but upbeat, eating Cheerios and toast from her tray.

(I still regret that this was her last meal. Wish I’d brought her a fresh bagel with lox.)

/15

A few hours later, her room was packed with family and friends. It was literally a party.

There was talking and laughing and cognac in Dixie cups. The mood was anything but funereal.

They gathered around her bed. I took a group photo. Everyone was smiling.

/16

There was talking and laughing and cognac in Dixie cups. The mood was anything but funereal.

They gathered around her bed. I took a group photo. Everyone was smiling.

/16

I then watched as a colleague reviewed everything one last time, confirmed her wishes, explained what would happen, and answered everyone’s questions.

“Okay, I’m ready,” she said. Her composure was remarkable.

“Goodbye everyone. Thank you for everything. I love you all.”

/17

“Okay, I’m ready,” she said. Her composure was remarkable.

“Goodbye everyone. Thank you for everything. I love you all.”

/17

She received midazolam and dozed off peacefully, her children holding her hands and stroking her head.

Next came propofol, an anaesthetic.

Then rocuronium, a muscle relaxant.

Finally, potassium chloride, to stop her heart.

Five minutes after saying goodbye, she was dead.

/18

Next came propofol, an anaesthetic.

Then rocuronium, a muscle relaxant.

Finally, potassium chloride, to stop her heart.

Five minutes after saying goodbye, she was dead.

/18

There were tears, of course. All around. But mostly the atmosphere in the room was one of serenity and gratitude, and a genuine sense of having done the right thing.

/19

/19

I’m no MAiD expert, and I get that some people are opposed to it for various reasons. But I’ve been a doctor for 25 years, and I’ve seen enough deaths to know a good one from a bad one.

This was, without exaggeration, the best death I have ever witnessed.

/20

This was, without exaggeration, the best death I have ever witnessed.

/20

We all die eventually. This patient helped me realize that when my time comes, I'll be fortunate if MAiD is an option.

And I will always be thankful to her, her family, and a very skilled colleague for helping me appreciate just how good a “good death” can be.

/ end

And I will always be thankful to her, her family, and a very skilled colleague for helping me appreciate just how good a “good death” can be.

/ end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh