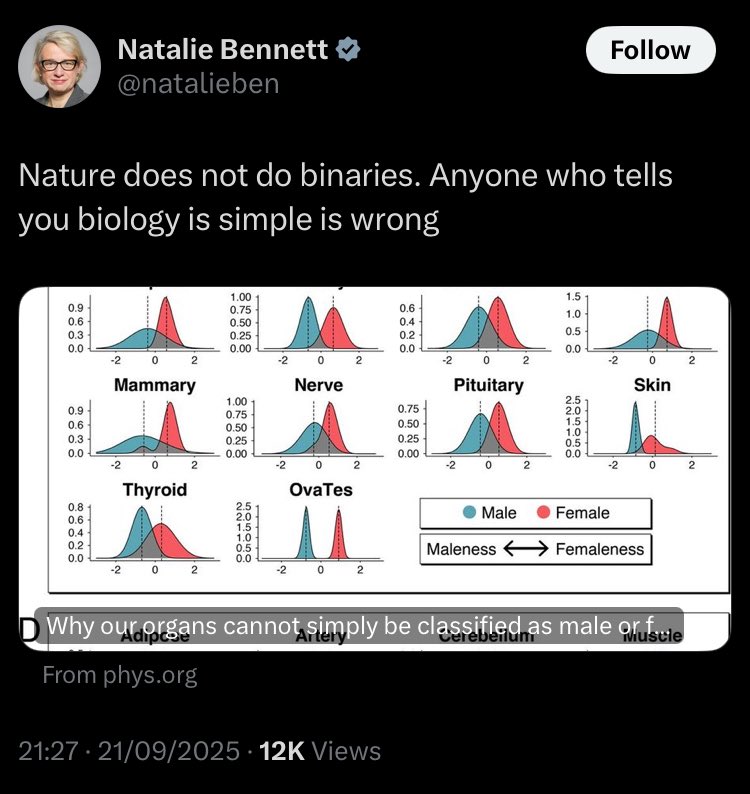

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: Oh look, half the people have a dangly thing between their legs and the other half are way less weird looking. I wonder if this division is important?

RW: Nah, I don’t think so.

RW: Nah, I don’t think so.

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: But look, the majority of the little people seem to be associated with two big people, one of each type, and the really little people spend a lot of time inside then fixed via their mouth to just one type of big person.

RW: I don’t see it.

RW: I don’t see it.

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: If you look at all the other life around these parts, they also seem to be divided into two main groups of body type. This seems pretty universal, now I look deeper. Are you sure this isn’t important?

RW: Ignore it.

RW: Ignore it.

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: I really think I should consider whether I’ve discovered something fundamental here. Someone might give me a prize.

RW: I think we should group people not according to whether they *have* dangly or undangly bits, but whether they *want* dangly or undangly bits.

RW: I think we should group people not according to whether they *have* dangly or undangly bits, but whether they *want* dangly or undangly bits.

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: <doubtful look>

RW: Yes, that makes a lot more sense as a categorisation.

Scientist: OK, but I’m going to carry on studying the Danglies and Undanglies. <gets labcoat on and runs after passing Dangly>

RW: Yes, that makes a lot more sense as a categorisation.

Scientist: OK, but I’m going to carry on studying the Danglies and Undanglies. <gets labcoat on and runs after passing Dangly>

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon RW: <calling> Hang on, how do you know that person is a Dangly?

Scientist: <points to dangly bits>

RW: That’s a bit presumptuous though.

Scientist: <bats dangly bits>

RW: What if this person is really an Undangly?

Scientist: <eyes dart between RW and gently swaying dangly bits>

Scientist: <points to dangly bits>

RW: That’s a bit presumptuous though.

Scientist: <bats dangly bits>

RW: What if this person is really an Undangly?

Scientist: <eyes dart between RW and gently swaying dangly bits>

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon Scientist: I’ve discovered something cool about Danglies. Wanna hear?

RW: You can’t call them that.

Scientist: W..what? Do you remember back there when I swatted one of them?

RW: That wasn’t a Dangly.

Scientist: It dangled.

RW: You can’t call them that.

Scientist: W..what? Do you remember back there when I swatted one of them?

RW: That wasn’t a Dangly.

Scientist: It dangled.

@JaneSpeakman1 @HJJoyceEcon RW: That’s not how we recognise Danglies. We recognise them by their internal sense of Dangliness.

Scientist: I can’t see inside their heads.

RW: They don’t have Dangly brains.

Scientists: <backing away slowly> But you clearly have a lot of dangle going on in your head. I’m off.

Scientist: I can’t see inside their heads.

RW: They don’t have Dangly brains.

Scientists: <backing away slowly> But you clearly have a lot of dangle going on in your head. I’m off.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh