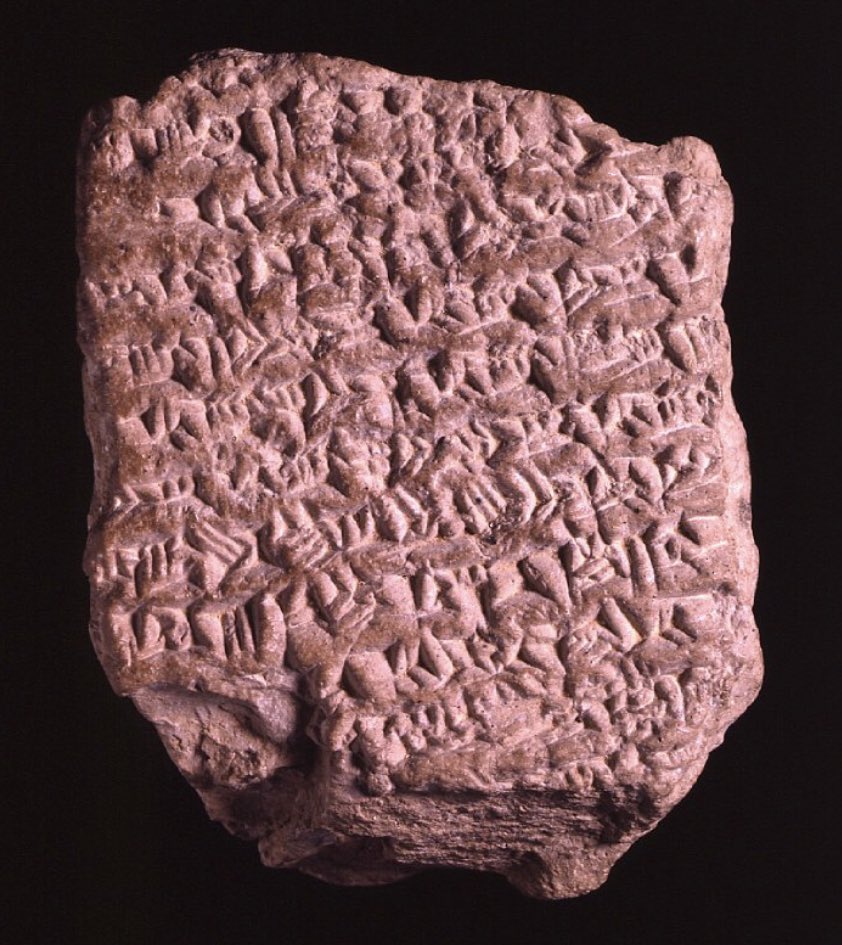

I opened a lecture on the history of astronomy in ancient Mesopotamia today by acknowledging that cuneiform tablets, to an untrained eye, can look like dog biscuits. But what they lack in aesthetics, they make up for in content.

Especially when it comes to the sky. Thread.

Especially when it comes to the sky. Thread.

2,000 years before Pythagoras realised that the morning and evening stars were one and the same — the planet, Venus — a scribe in Uruk describes a festival of the morning and evening Inana, the Sumerian goddess of love and war associated with Venus cdli.ucla.edu/search/archiva…

Not that every accomplishment needs to be measured against those of “Classical” civilisations, but I am sick to death of hearing that astronomy, medicine, poetry, etc were born in Ancient Greece, as if science and scholarship were and are a uniquely Western enterprise

In the Old Babylonian period (c2000-1600 BCE), scholars began systematically to record celestial phenomena and their related terrestrial events. These took the form of omens, most of which were concerned with the moon and lunar eclipses britishmuseum.org/research/colle…

Eventually, celestial omens were compiled into a “canonical” compendium, Enūma Anu Enlil, which was copied in pretty much the same form for centuries and which sat within a constellation of related scholarly texts, like commentaries

It was 70 tablets long with thousands of omens

It was 70 tablets long with thousands of omens

To quote @SethLSanders who manages to capture in one concise Tweet just how salient this text was in scholarly circles

https://twitter.com/sethlsanders/status/1148074653845356545?s=21

To oversimply a very complex history because this is a Tweet, the observational framework structured by omens develops into the framework for observational astronomy that appears in the first millennium BCE.

Enter, Astronomical Diaries.

Enter, Astronomical Diaries.

Astronomical Diaries are *so* cool.

They record daily astronomical observations in detail, like the position of the moon, occurrences of eclipses, and the location of planets in the sky.

They also record earthly affairs like the price of barley and the level of the Euphrates

They record daily astronomical observations in detail, like the position of the moon, occurrences of eclipses, and the location of planets in the sky.

They also record earthly affairs like the price of barley and the level of the Euphrates

Cuneiform Astronomical Diaries record observations of stuff happening in the sky and stuff happening below, from the mundane to the major.

Including the death of Alexander the Great.

“...first part of the night, Mercury was 14 fingers above Saturn...The 29th, the king died.”

Including the death of Alexander the Great.

“...first part of the night, Mercury was 14 fingers above Saturn...The 29th, the king died.”

Reading cuneiform astronomical texts, one is often reminded of the opening lines of a Babylonian epic known as Enūma eliš that divides the world into sky above and earth below.

“When on high, the heavens we’re not named, and below the earth had no name.” lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/csar/fil…

“When on high, the heavens we’re not named, and below the earth had no name.” lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/csar/fil…

What I love about the Late Babylonian Astronomical Diaries is that they record and make sense of the same phenomena that we observe today.

From the position of Venus in the night sky to Halley’s comet, we can see the world through ancient eyes and our own at the same time.

From the position of Venus in the night sky to Halley’s comet, we can see the world through ancient eyes and our own at the same time.

IMHO this is what makes the history of science extremely fucking cool

Cuneiform tablets might not be the most beautiful artefacts from the ancient world, but they open up a window onto some of the earliest attempts to make sense of the universe in a systematic way - of science-ing.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh