The Fixed-term Parliaments Act diagram in this BBC story is reasonably good. But it seems to based on what I call the "more deferred duty to resign" theory of the Act. That's not the best theory. bbc.co.uk/news/uk-493912… (1)

The problem is the little box that asks "Can MPs agree on alternative PM?". You only need to ask that question if you think the PM needn't resign unless and until someone else has a majority (or something). But that's a flawed way of thinking about it. (2)

You could have a minority group that was not far short of a majority, that could govern at least for a period—like Labour in 1974, say. The big question is whether you think the FTPA now locks such a minority government out (as the BBC diagram implies). (3)

I don't think it does, or should. It's far better to see the PM as having a duty to resign as soon as he's definitely lost the confidence of the Commons, rather than being entitled to hang on till someone else has it. (4)

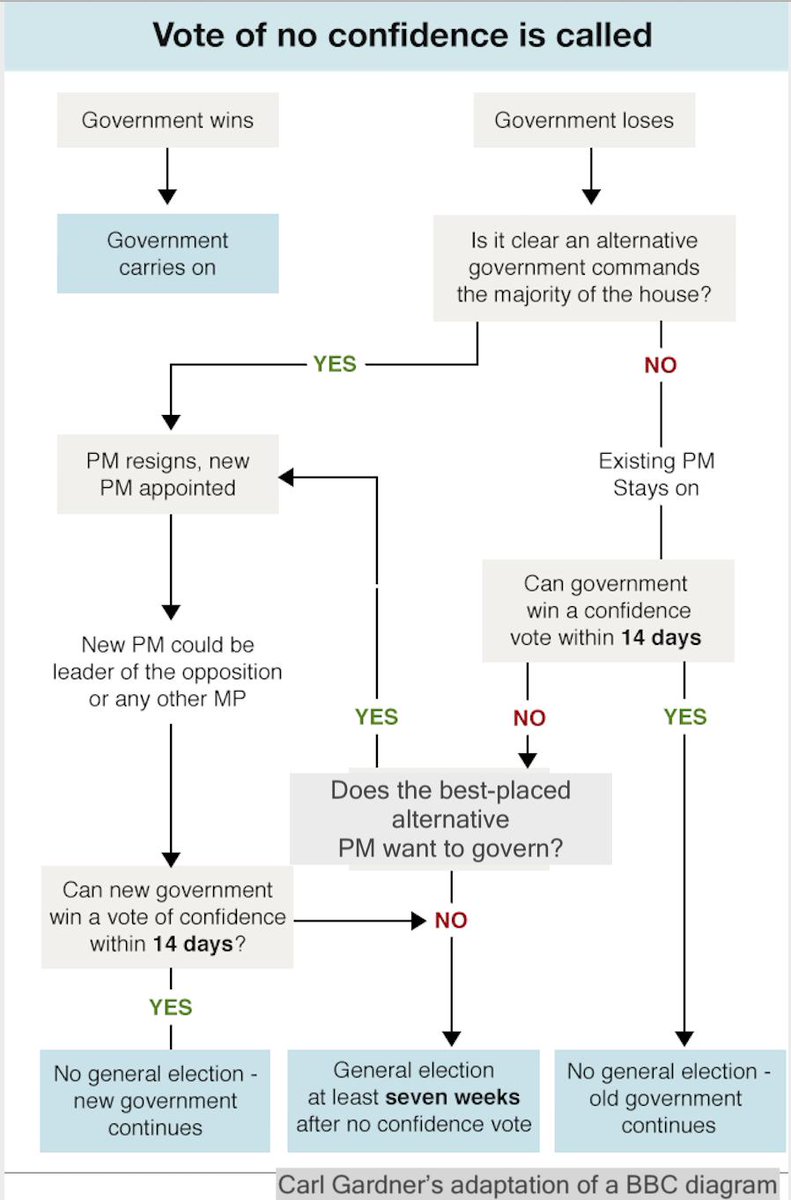

So here’s my version of the diagram. This represents the “less deferred duty to resign” theory of the FTPA, which I think is correct. (5)

This has two advantages over the BBC's diagram. First, it aligns with what we know about precedent. It allows for incoming minority governments, which is something we have had in the past. So this is a descriptively more accurate theory. (6)

Second, this theory aligns much more closely with the traditional idea that the government needs to have the confidence of the Commons. On this theory, the PM needs to resign once this confidence is definitively lost. So it's a normatively more desirable theory. (7)

If the PM has lost the confidence of the House and all credible alternatives want an election, fine—on my theory, you get one. But a no-confidenced PM shouldn't have the unilateral right to lock them out. That's the problem with the BBC diagram and the "more deferred" theory. (8)

Important, in working out whether you agree with the BBC's implied theory or my explicit one, to put out of your mind any partisan considerations such as the identity of any incumbent and alternative PM. (9/9)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh