The Most Read article in @AmJEpi is a simple, but important, 2013 paper on gun ownership & suicide death in the US.

Critics argue you can’t make cause & effect conclusions based on ecological studies, but is that always true?

Let’s discuss! #epiellie

academic.oup.com/aje/article/17…

Critics argue you can’t make cause & effect conclusions based on ecological studies, but is that always true?

Let’s discuss! #epiellie

academic.oup.com/aje/article/17…

So let’s start with some background. What is an ecological study?

It may sound like it’s about the environment, but that’s not really true.

In epidemiology, an ecological study is one where all data about groups not individuals.

It may sound like it’s about the environment, but that’s not really true.

In epidemiology, an ecological study is one where all data about groups not individuals.

What does that mean?

For example, we might know how much chocolate per capita is eaten in countries around the world and we might also know how many Nobel Prize winners each country has had.

nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

For example, we might know how much chocolate per capita is eaten in countries around the world and we might also know how many Nobel Prize winners each country has had.

nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

When we compare those two numbers, we see something surprising...

the more chocolate a country eats, the more Nobel Prize winners they have! 😱🥳

the more chocolate a country eats, the more Nobel Prize winners they have! 😱🥳

Does that mean if we want to be great scientists we should start gorging on chocolate?

Well, I’m not going to tell you not to eat chocolate, but it’s not that simple because of a problem called the Ecological Fallacy....

Well, I’m not going to tell you not to eat chocolate, but it’s not that simple because of a problem called the Ecological Fallacy....

Okay, what does this new term mean?

The ecological fallacy is a mistake in reasoning that we can make when we assume that a process or relationship at the group level also applies at the individual level—sometimes they do apply but often they don’t!

The ecological fallacy is a mistake in reasoning that we can make when we assume that a process or relationship at the group level also applies at the individual level—sometimes they do apply but often they don’t!

In the chocolate study, *even if it’s true* that we could increase a *country’s* Nobel Prizes by increasing the average chocolate eating, the ecological fallacy tells us we can’t conclude an *individual* can increase their own chance of a Nobel Prize by eating more chocolate.

As a side note, also note we can make a mistake by thinking the reverse — the Aggregation Fallacy is when we incorrectly assume things that happen to individuals will also happen to groups.

A summary of these terms here 👇🏼

A summary of these terms here 👇🏼

Okay, but what does this have to do with our gun study? Well, this study was an ecological study.

The authors looked at the frequency of gun ownership at the state-level in the US and the frequency of suicide deaths by firearm & by non-firearm means.

These are group data!

The authors looked at the frequency of gun ownership at the state-level in the US and the frequency of suicide deaths by firearm & by non-firearm means.

These are group data!

What they found was pretty darn compelling!

States with higher gun ownership had more suicide deaths & more firearm suicide deaths than states with low gun ownership, but the *same* frequency of non-firearm suicide deaths.

States with higher gun ownership had more suicide deaths & more firearm suicide deaths than states with low gun ownership, but the *same* frequency of non-firearm suicide deaths.

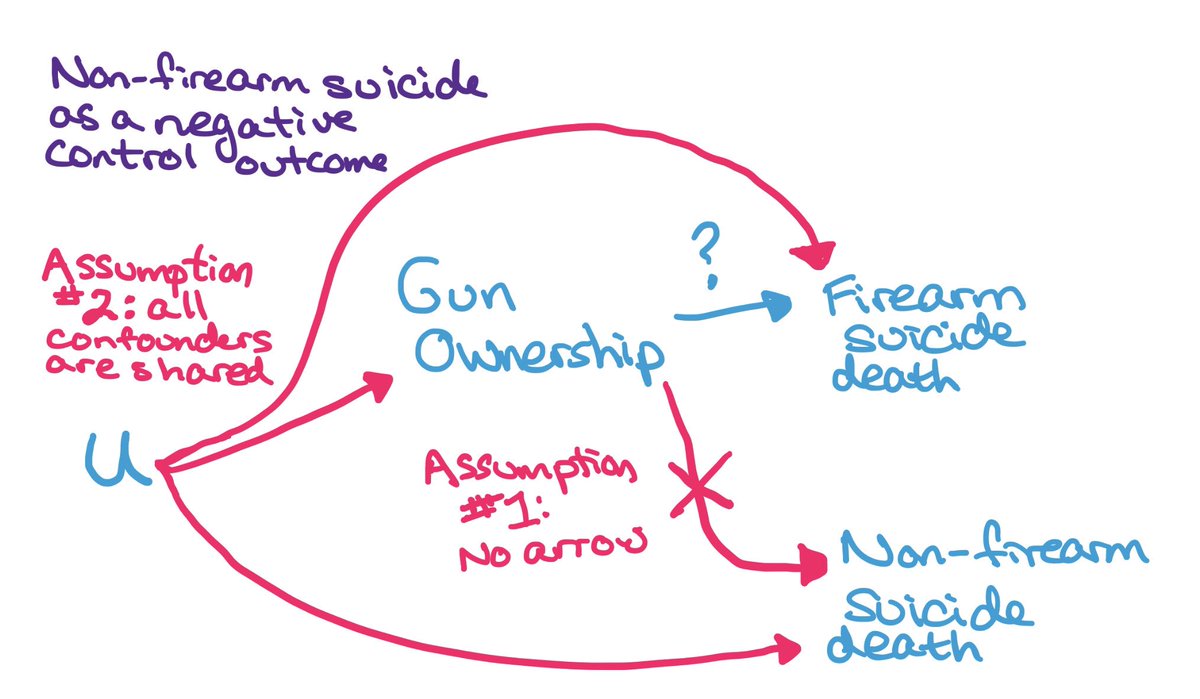

In this ecological study, non-firearm suicide deaths are acting as a “negative control outcome”: the authors believe that gun ownership shouldn’t affect suicide deaths by non-firearm means, and that they believe that any & all gun-suicide confounders are shared by method👇🏼

If our assumptions are right, then when we control for all the shared confounders & find that gun ownership & non-firearm death are not associated, this should provide support that our model for the relationship between gun ownership & firearm death has no unmeasured confounding.

This isn’t my subject area of expertise, so personally I’m not sure I can judge these assumptions. But what do you think?

First, are all confounders likely to be shared?

(Click to expand #epiquiz poll options)

First, are all confounders likely to be shared?

(Click to expand #epiquiz poll options)

Second, do you agree that we should expect non-firearm suicide deaths not to be causally related to gun ownership?

(Click to expand #epiquiz poll options)

(Click to expand #epiquiz poll options)

To conclude state-level cause & effect, we need to make all the causal inference assumptions:

•no unmeasured confounding

•positivity

•well-defined interventions

•no unmeasured confounding

•positivity

•well-defined interventions

If you believe the two assumptions in the polls, then it seems reasonable to conclude that there is no unmeasured confounding here... although the graph is actually not adjusted at all, but maybe there is no confounding 🤷🏼♀️?

Positivity means that all states could have had any level of gun ownership. I’m not sure how feasible that is, but certainly all states could have some levels off gun ownership.

Lastly, well-defined interventions means we know why & how state gun ownership levels change. That’s a bit tricky, and we may not be comfortable with it.

But, given all of those assumptions, at the *state* level, are you ready to conclude that having a higher percentage of the population owning guns is a cause of increased firearm-related suicide?

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

What about the flip side? Are you ready to conclude that having lower gun ownership is *protective* for firearm suicide deaths at the state level?

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

What about the ecological fallacy? It isn’t always relevant but we need to assess it.

To help, let’s consider the classic example of the relationship between religion and suicide postulated by Emil Durkheim in 1897 based on ecological (region-level) data.

To help, let’s consider the classic example of the relationship between religion and suicide postulated by Emil Durkheim in 1897 based on ecological (region-level) data.

He noticed suicide death was more common in Protestant than Catholic areas & concluded Protestants were more likely to attempt suicide.

But later studies showed he had likely made an ecological fallacy: increased death in Protestant areas was among *Catholics*, not Protestants.

But later studies showed he had likely made an ecological fallacy: increased death in Protestant areas was among *Catholics*, not Protestants.

One explanation is that it was more difficult to be a Catholic minority in a Protestant region leading to more deaths.

Another is there was pressure to not record suicide death among Catholics in Catholic areas, but this was reduced in Protestant areas.

jstor.org/stable/2096361…

Another is there was pressure to not record suicide death among Catholics in Catholic areas, but this was reduced in Protestant areas.

jstor.org/stable/2096361…

So, could that be what’s happening here? Is the ecological fallacy an issue?

Would it be likely that the increase in firearm suicide deaths is among people who are *not* the gun owners?

What about among people who don’t even have access to the gun owners?

Would it be likely that the increase in firearm suicide deaths is among people who are *not* the gun owners?

What about among people who don’t even have access to the gun owners?

So, what do you think?

Putting together the assumptions for state-level conclusions & whether the ecological fallacy is a concern here, are you okay concluding *individual* gun ownership is a cause of firearm suicide death in the US?

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

Putting together the assumptions for state-level conclusions & whether the ecological fallacy is a concern here, are you okay concluding *individual* gun ownership is a cause of firearm suicide death in the US?

(Click to expand #epipoll quiz options)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh