Here's a quick thread about how the travails of Cathay Pacific could be just the tip of the iceberg for Swire Group, as it tries to reconcile its British colonial legacy and Beijing's creeping control over Hong Kong:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Once upon a time, economic life in Hong Kong and Shanghai was dominated by the hongs, mostly British-owned trading houses which monopolized China's trade with the British empire.

Most were established in the mid-19th century, in the period when Britain was using opium and the rhetoric of free trade to extend its influence in China:

https://twitter.com/davidfickling/status/1017658014394826753?s=20

Many disappeared or changed over the years.

HSBC started out as a hong, and Li Ka-shing's CK empire grew on the back of its takeover of the old Hutchison and Whampoa hongs.

Just two still retain the form of British-run family businesses, though: Swire and Jardine Matheson.

HSBC started out as a hong, and Li Ka-shing's CK empire grew on the back of its takeover of the old Hutchison and Whampoa hongs.

Just two still retain the form of British-run family businesses, though: Swire and Jardine Matheson.

China's Communist Party has long given the Opium Wars a central role in its historical iconography. For Xi Jinping, the era was one of "humiliation and sorrow", in the words of a 2017 speech in Hong Kong marking its return to China: scmp.com/news/hong-kong…

That meant that as the 1997 handover approached, the tai-pans who ran the remaining hongs had to decide how to survive in the new era. Jardines had started life as an opium trader; Swire, too, benefited from the hated "unequal treaties" that opened China up to trade.

In a way it was a little like the grand wagers on the future of Asia made by the protagonists of James Clavell's novels about the era. In my view, Swire bet on the wrong horse.

Jardines' approach was to diversify away from Hong Kong and China and towards southeast Asia. Most of its businesses are now listed in London and Singapore and incorporated in Bermuda, although HQ is still in Hong Kong.

HSBC did more or less the same thing with its takeover of the UK's Midland Bank and reincorporation in London:

Li Ka-shing, too, has built an empire whose assets are mainly in Europe and North America, leaving him arguably as exposed to Brexit as a Chinese crackdown in Hong Kong.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Only Swire decided to throw its lot in with Beijing, tying up with Citic Ltd. (the investment company set up with Deng Xiaoping's blessing); buying Coke bottling plants, offices, malls, and food businesses in the mainland; and working to build its mainland aviation network too.

It was clear even in the 1990s that this strategy wouldn't work if Swire continued to be run by expat Old Etonians the way it had been since the 19th century.

As Cathay built up its mainland presence with the takeover of Dragonair, it promoted a group of Hong Kong-born executives to top jobs, among them Philip Chen and Augustus Tang.

Astonishingly, despite the obvious liability of looking like a relic of British colonialism in Hong Kong in the 21st century, that didn't really get very far.

Swire is still largely run by "Swire boys", expat Brits who've bounced around Asia since the 1980s/1990s.

Swire is still largely run by "Swire boys", expat Brits who've bounced around Asia since the 1980s/1990s.

Cathay Pacific, treated as the crown jewel of Swire despite a pretty small share of earnings, has a weirdly ritualized 30-year apprenticeship path for CEOs.

Incoming boss Augustus Tang will be just the third ethnic Chinese CEO in its >70-year history:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Incoming boss Augustus Tang will be just the third ethnic Chinese CEO in its >70-year history:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

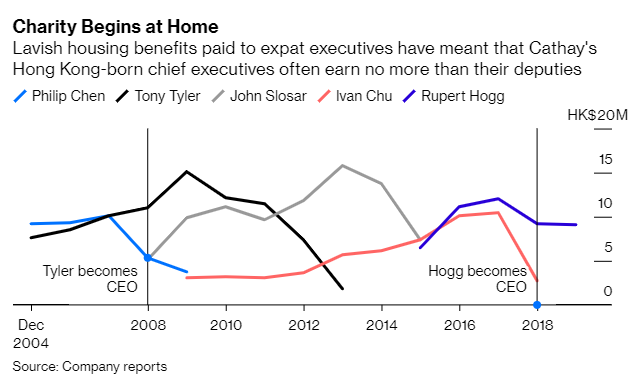

That's not all. Swire boys tend to get lavish housing benefits which means that even when there's been ethnic Chinese CEOs at Cathay, their expat deputies have often been equally well-paid, or better:

Meanwhile the ethnic Chinese representation on the board of the listed holding co. Swire Pacific, at about 36%, is now the lowest it's been since 2003.

(Jardines is arguably worse, with just four Asian faces on the board alongside three members of the founding Keswick family)

(Jardines is arguably worse, with just four Asian faces on the board alongside three members of the founding Keswick family)

In a way it seems churlish to draw attention to Swire's failure to promote Hong Kong talent at a time when Hong Kong's very freedoms are under assault from Beijing. China's crackdown is clearly the bigger issue for Hong Kong itself.

But for Swire, the retention of this stodgy British culture is an unforced error. Thanks to the decision to throw its lot in with China, it has one of the highest exposures to mainland China of local companies on Hong Kong's Hang Seng index:

If you're going to throw your lot in with a government that sees anti-colonialism as part of its DNA, it would be a really good idea to not look like a relic of British colonialism. But Swire has singularly failed to do this.

It's hardly surprising that Swire, and Cathay, have been so quick to bow to Beijing's demands. The business is deeply dependent on the Chinese government's goodwill.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

But more circumspect bosses might have seen how the British-dominated Swire boys culture needlessly aggravates this relationship, and might also have seen the simply commercial benefits of removing the bamboo ceiling and giving more power to Asian executives who know the region.

Former Cathay CEO Ivan Chu might be a good way to start this. His role is currently more or less lieutenant to Swire executive chairman (and great-great-great grandson of the founder) Merlin Swire:

He was born in Hong Kong and grew up with memories of the 1967 protests, then kicked around China for a few years after university before joining Swire in 1984.

As well as being a Swire loyalist, he's also a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which technically makes him a sort of politician/legislator though in effect the CPPCC is like a Rotary Club for China's wealthy and powerful.

Swire remains on a collision course with Beijing unless it plays its cards very carefully. The big risk waiting in the wings would be if Cathay's 30% shareholder Air China made Swire an offer it couldn't refuse for control of the airline: bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

Just as Swire itself is a symbolic thorn in the side of Beijing's self-image, Cathay Pacific remains a potent symbol of Hong Kong's unique status that China would be quite happy to see erased:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

If Swire wants to have continued relevance as an emblem of how Hong Kong is proudly different to mainland China, it really needs to make itself look a bit more like Hong Kong itself, rather than a throwback to the British Empire. (ends)

PS here's the article! bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

PPS this is a great deep dive by @Jamie_Freed into Swire's unique, antiquated corporate culture: uk.reuters.com/article/uk-cat…

PPPS you should also read this great piece from @JournoDannyAero on change at the top of Cathay: amp.scmp.com/news/hong-kong…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh