If you object to historical research because of the implications you think it has for present-day institutions or ideals, the history isn't "politicized." Your response is.

The same can of course be said for *approving* of historical research because of its perceived present-day implications -- whether these issue in demands for change or celebrations of the status quo.

The point is that how we *respond to* history is almost inevitably "political."

Blaming historians for this, or judging research by it, is foolish.

Insisting that they produce research that *has* no implications -- or, what is often meant, conservative ones -- is utterly vain.

Blaming historians for this, or judging research by it, is foolish.

Insisting that they produce research that *has* no implications -- or, what is often meant, conservative ones -- is utterly vain.

When the response to archival research is, "This delegitimizes America!", a historian, as a historian, can only reply: "So what? I'm not responsible for sustaining your beliefs."

If the demand is to *produce* work that "legitimizes" America, it's not history that's being requested. It's propaganda.

All of these are very simple points. Every one of them has been ignored in right-wing responses to 1619. And in responses to work on the Roman Empire. And the Middle Ages. And the Scientific Revolution. And the Enlightenment.

In a recent thread, I alluded to a crisis in public history, by which I really meant the public reception of academic history, or of history based on academic work. This crisis turns on the misunderstanding -- and willed misrepresentation -- of basic historiographical concepts.

In this it is part of a broader crisis of expertise, as scientists were quick to remind me. In both instances, the fact that research has implications for the present -- implications that are subject to political contestation -- is used to discredit the research as "politicized."

However I do think that history -- perhaps like all the discrete disciplines wrapped up in this crisis -- has a specific relationship to the public, and to the particular interests at stake in the politics of responding to the past. So it's not *just* a question of expertise.

For one thing, I suspect relatively few "critics" of climate science think they know *more* about climate than scientists. My sense is that they dismiss the scientific consensus as "politicized" or "self-interested" and leave positive counterclaims to "dissident" scientists.

With history, by contrast, my sense is that a great many people think they know better than historians the history of their country, their religion, their civilization -- precisely because it *is* "theirs". Their identity is wrapped up in it, and in a particular narrative of it.

This is what makes work like 1619 both important and contentious. It is not just engaged in teaching new facts but in changing a narrative that is central to many people's sense of who they are, what kind of people they are, what their values mean.

The conservative response it has provoked testifies to this. The objections have next to no relation to the ways it was researched or to the factual claims made. Some pedantic quibbling aside, they centre almost wholly on its implications for how America is seen and sees itself.

In this it is not just revealing of the politics of history in the US but also indicative of the nature of responses to other historical research. And it is distinct from resistance to scientific work on climate change, notwithstanding the vital relevance that has for all of us.

The specificity of this problem to history may supply a unique opportunity -- to make the work of historians not merely accessible (in the form of new narratives) but also conceptually *transparent* to a public that clearly perceives its own stake in the past.

But this depends not only on offering a new narrative but also on showing the work that goes into making narratives in the first place. Like scientific work, this is not work anyone can *do*. But to a great extent it is work that most people can -- perhaps need to -- understand.

This means that a lot hinges on how new narratives are presented and, especially, how the academic work behind them is *represented*. More than represented: brought into the public realm.

On this front, I've seen a one or two criticisms of 1619 that do hit home. Here I must offer the caveat that I am not a specialist in early American history or slavery, though my work has touched glancingly on both. Anyway, I am a professional historian and an experienced reader.

So, one thing that was noticeable -- and a strength -- of 1619 is that the pieces cite many of the historians whose work is used.

One thing I didn't (as a nonspecialist) immediately notice, but should (as a historian and magazine reader) have guessed, is that many more weren't.

One thing I didn't (as a nonspecialist) immediately notice, but should (as a historian and magazine reader) have guessed, is that many more weren't.

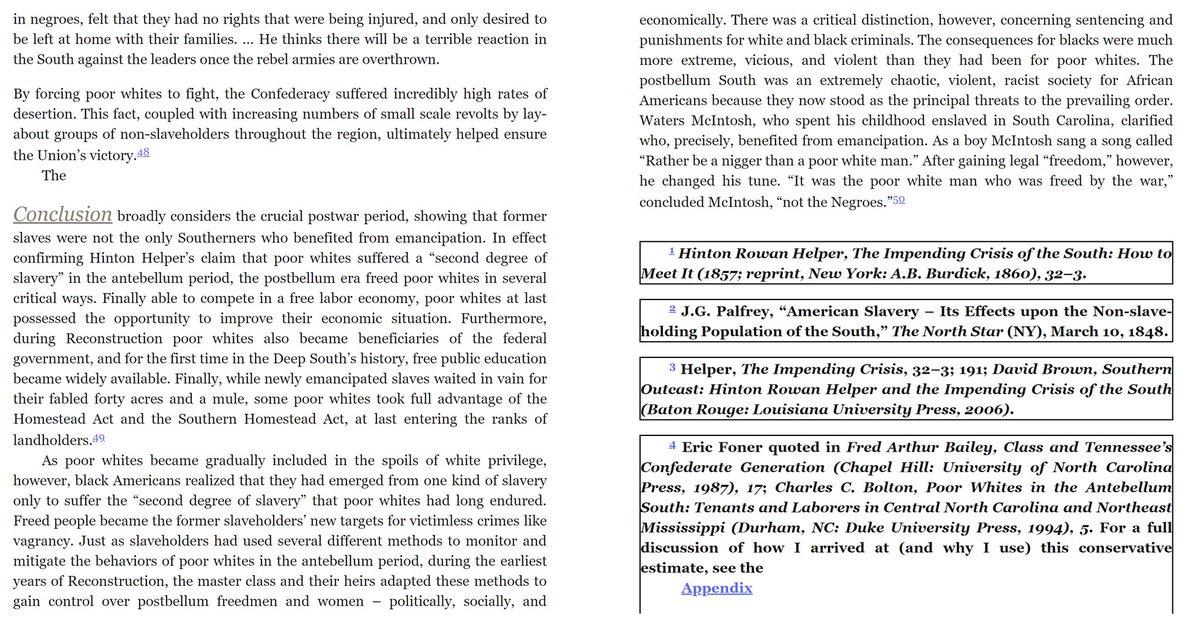

Here's an example. The first image below is from the lead piece in 1619, by Nikole Hannah-Jones. The second is from the introduction to @KeriLeighMerrit's book Masterless Men.

Now, I have no idea how the editorial process works at NYT Magazine. And I know very well that mass-media publications routinely assimilate the work of scholars without giving them specific (read: any) credit. They don't "do" footnotes.

But there are at least three things that need attention, I think.

One is the basic principle of giving credit where it's due. This is no mere academic hangup, and house style is really not an excuse here.

One is the basic principle of giving credit where it's due. This is no mere academic hangup, and house style is really not an excuse here.

The second, closely related, is that in fact credit *was* given to several historians, in the body of the text. In the instances I've seen (I haven't read every piece) these were more often men than women, more often senior than junior, and more often at prestigious universities.

So we have here either an authorial or an editorial decision to accord credit for scholarship only patchily and unevenly, with the field seemingly tilted towards those in positions of relative power. Reading from the sidelines, I admit, this is an unfortunate irony.

But third -- besides wronging Merritt and other scholars, more than reason enough for a rethink -- this is also a colossal missed opportunity. Its a missed opportunity to make visible not just the *upshot* of scholarship but the processes and the scholars themselves behind it.

One of the best features of 1619 is its presentation. The way the whole thing flows, and the way related stories appear as pockets -- rabbit-holes -- within a larger project. It's evocative of the research process, wherein the pursuit of a big question branches out unpredictably.

Surely so innovative and evocative a presentation creates rather than closes off avenues to the scholars themselves. Why not at least link to them or their work? Why not find ways to bring them in, perhaps even interactively?

The irony here is that some of the scholars involved, like Merritt, are *already* doing the work of reaching publics on social media. They are not locked away in Ivory Towers. They are out there. In a project geared to changing a *public* narrative, why not *use* that strength?

Anyway, I guess these are properly questions for @NYTmag and @nytimes. Perhaps there are ways of redressing these problems now; there was talk yesterday of a #1619Syllabus, for example.

Finally: getting this right is about crediting the *work* that went into it.

But it is also about making these projects *work* better, so that instead of inviting predictable charges of "politicization", they make scholars visible and their work transparent to the public.

But it is also about making these projects *work* better, so that instead of inviting predictable charges of "politicization", they make scholars visible and their work transparent to the public.

*It's

who will rid me of these pestilent typos

who will rid me of these pestilent typos

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh