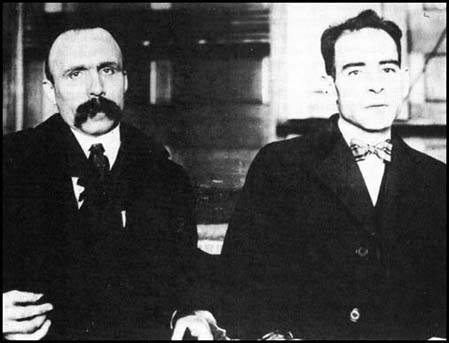

This Day in Labor History: August 23, 1927. The state of Massachusetts executed two Italian immigrant anarchists by the names of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti for the murder of two men in 1920. Let's talk about one of the most unjust trials in labor history.

Sacco and Vanzetti were anarchists, men deeply affected by the terrible labor and social conditions of the early 20th century. Both immigrated from Italy in 1908, though they didn’t meet for nearly a decade.

The seeming inability for the capitalist system to treat working people with dignity and respect drove many to desperation.

By the 1890s, anarchism was a growing threat in the United States, perhaps most personified by Leon Czoglosz’s assassination of President William McKinley in 1901.

Although that and other incidents convinced enough upper and middle-class Anglo-Saxons to enact limited reforms during the Progressive Era, the fundamental conditions of working-class urban life had changed little by 1920.

Sacco and Vanzetti both followed the teachings of Luigi Galleani, an anarchist theorist who advocated violence to overthrow the state. The Galleanists did in fact use violence in the United States.

They were believed to be the group behind the bombing of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s home in 1919. Kind of too bad they didn't finish the job.

Palmer, already cracking down on radicalism with the help of his young eager assistant by the name of J. Edgar Hoover, built upon this incident to intensify the Red Scare, that nation-wide crackdown on radicalism in all forms during and after American entry into World War I.

It was in this atmosphere that men like Sacco and Vanzetti were suspects in murders like that which took place on April 15, 1920, when armed robbers attacked a company payroll, killing two men.

Although the evidence was indirect, the police suspected the greater Boston anarchist community, which was suspected in a series of other robberies to fund their activities.

The police also discovered that one anarchist, Mario Buda had worked in two shops subjected to similar robberies. Upon questioning, Buda let slip that the local anarchist community had an automobile under repair, leading police to stake out the repair shop.

The police convinced the garage owner to notify them when the anarchists arrived to pick up the car. When 4 men did, including Buda, Sacco, and Vanzetti, they sensed a trap and fled, but Sacco and Vanzetti were soon picked up.

Both had guns at their homes; Sacco having a loaded .32 Colt similar to that used in the killings.

I’m not going to get into the details of the case, they are easy enough to read about if you want. Suffice it to say that the evidence was dicey that these two men committed the crime.

It is at least possible that Sacco was directly involved, but Vanzetti was an intellectual and not a man of action; as John Dos Passos wrote in his defense of the men, “nobody in his right mind who was planning such a crime would take a man like that along.”

Given the firearm evidence, the case against Vanzetti was far weaker than that against Sacco.

The trial was a farce. The judge, Webster Thayer, was a conservative who had openly called for a crackdown against Bolsheviks and anarchists and held deep prejudice against immigrants. Taylor asked for the assignment so he could make an example of Sacco and Vanzetti.

After denying an appeal motion, Thayer famously told a lawyer, “Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?”

He told reporters that “No long-haired anarchist from California can run this court!” Despite his bias, Thayer controlled the trial proceedings until the executions.

What can’t be denied is that Sacco and Vanzetti called for violent revenge due to their arrest, trial, and conviction. And their friends delivered. Mario Buda set off a bomb on Wall Street after their indictment, killing 38 people. He then fled the country, returning to Italy.

Neither Sacco or Vanzetti ever renounced the sort of violence that they were accused of committing. Vanzetti called for the murder of Thayer. In 1932, a bomb blew up Thayer’s home in Worcester, Massachusetts, injuring his wife and housekeeper.

Sacco and Vanzetti’s case became the cause celebre of the 1920s. Not everyone claimed their innocence, but the behavior of Thayer and the unfair trial led to worldwide calls for a retrial.

Although anarchists and other radicals dominated the defense committee, the case caught the attention of many around the world who thought justice poorly served. People ranging from Albert Einstein to Edna St. Vincent Millay to H.G. Wells thought it a miscarriage of justice.

Even Benito Mussolini was ready to request clemency from the governor of Massachusetts if he thought it might do some good.

Among others, future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter called for a new trial. Thayer refused all these requests and Sacco and Vanzetti were executed on August 23, 1927.

Back on Sunday to discuss A. Philip Randolph and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh