Curious what happens when Safari launches with a new profile? Me too, so I fired up a proxy, and watched.

Here is what I found…

Here is what I found…

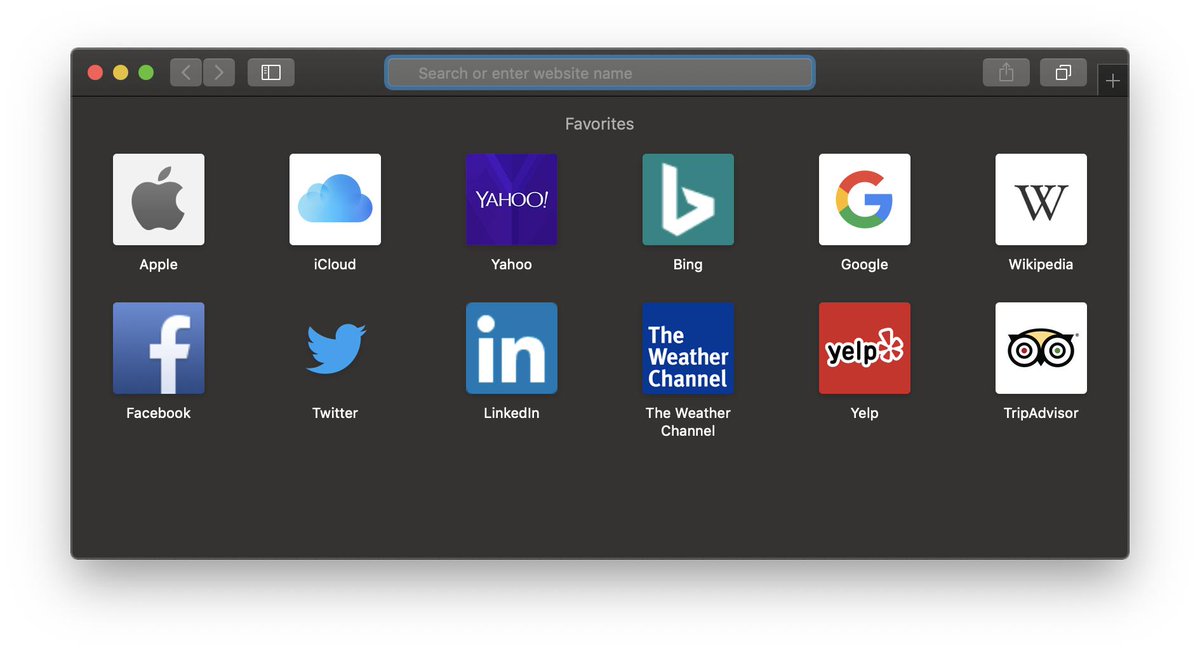

To kick this thread off, lets take a close look at that initial loading screen. For setup, I temporarily set aside the Library/Safari folder, thus giving myself a fresh profile on the subsequent launch. Check out those icons. Where do you think they're hosted/stored?

Safari launches with default 'favorites', each represented by a favicon. I assumed these would be local resources—I was wrong. Here's a look at the structure of requests produced by the proxy application. You'll notice overlaps between hosts and earlier favicons.

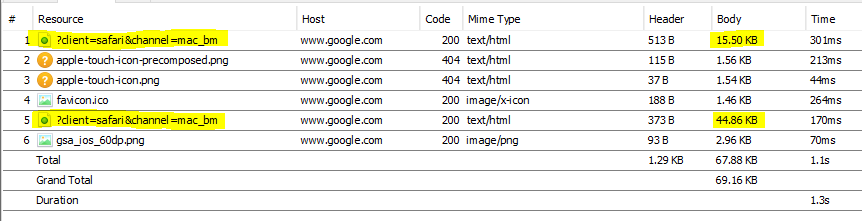

Safari issues numerous requests for just about each icon. The first is to apple.com, the page itself. I assume this then crawls the markup for meta tags containing links to Apple-ready icons. Oddly enough, this page does not have any relevant meta tags.

What you would expect to find is a link tag like <link rel="apple-touch-icon" href="icon.png">. iOS used to add effects to icons, but you could avoid that with a 'precomposed' image. Since iOS 7.0, effects are no longer added, so precomposed icons are less common.

All that said, Safari still looks for the precomposed icon and the default when a tag for neither is found. This bring us to our next request, for the 404'd precomposed image. Lastly, it issues a request for apple-touch-icon, which succeeds in loading the image. A cookie is set.

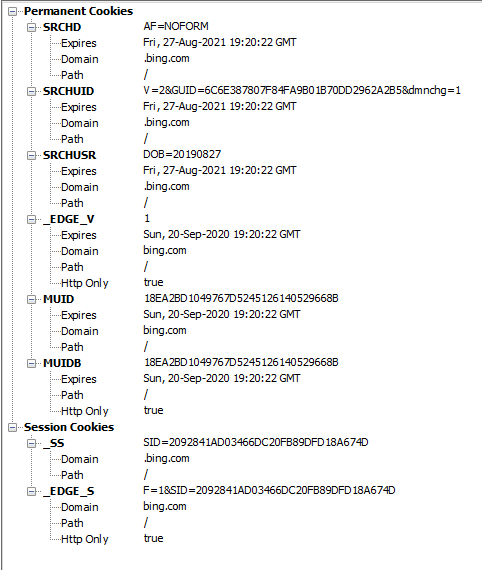

So for the first image, we issued 3 requests. Further, we acquired our first cookies before even using the browser. Next up, we'll need that Bing icon. Bing also lacks the meta tags, but has a precomposed image. Bing too will set several cookies.

This process repeats for the rest of these icons. For each, the domain is pinged. The markup (I assume) is crawled. If/when no relevant meta tags are found, Safari begins to look for known files. I suspect looking for known filenames first would save more data.

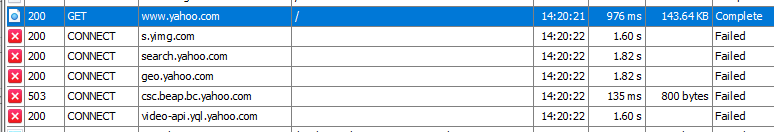

Our trip to gather up the Yahoo icon results in some failed DNS-prefetch and preconnect calls. These will be found in the <head> of the Yahoo site.

The next request is for google.com. Safari wasn't able to find either icon by its filename, but did see a meta tag in Google's source. Note, it requested the Google page twice; once with one ua-string, and again with the standard Safari ua-string. Also, more cookies!

I'm going to skip a bit here as this becomes redundant. Safari makes many other requests for icons on the first-run page. It is safe to assume each of these hosts sets one or more cookies, with few exceptions.

I'll end this thread with the following image, which shows hosts that were contacted during the first run of Safari on a fresh profile: Apple, Bing, Yahoo, Google, Wikipedia, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Weather, Yelp, Trip Advisor, and subsidiary host like abs.twimg, etc.

If you enjoyed this thread, be sure to check out previous first-run threads:

Opera

Vivaldi

Brave

Chrome

Firefox

Edge

Opera

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1165353213308129281

Vivaldi

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1165358155922059266

Brave

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1165391211999518720

Chrome

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1165493206441779200

Firefox

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1165858896176660480

Edge

https://twitter.com/jonathansampson/status/1166138692509065218

@threadreaderapp compile

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh