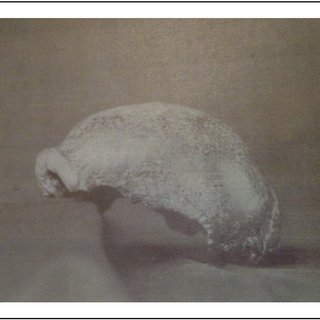

Today I visited a skull that is arguably my favorite fossil in paleoanthropology’s history, the Gibraltar Neanderthal from Forbes Quarry. Here’s why (a short #histsci thread):

The skull was discovered in 1848 and considered noteworthy enough to be presented at a meeting of the Gibraltar scientific society. They likely viewed the skull as simply human (though perhaps a slightly odd one) and left the specimen on a shelf to collect dust.

Over the next few years, it was packed away and shuffled around, before resting in a cabinet of the local library. Then, an event occurred—8 years later and 2,000 kilometers away—that brought the skull into the limelight: a similarly oddly shaped skull was uncovered in Germany.

Upon studying the German specimen, an expert in London put out a plea for more fossils. Future discoveries could determine whether the skull’s odd characters were ‘merely an individual peculiarity,’ or, in fact, features of a new kind of human.

This call for more fossils made the Forbes skull seem suddenly relevant, and the wish was granted. Freed from the cabinet, the Forbes skull was sent to London, where a publication was quickly fired off about the ‘Pithecoid Priscan Man’ (apelike, ancient man) from Gibraltar.

This Pithecoid Priscan Man proved that the German specimen was not ‘a mere individual oddity.’ Additionally, the Gibraltar skull was of ‘infinitely higher value’ than because it contained nearly the entire face, precisely the piece missing from the German skull.

Names were even considered to label it a new species, including the name Homo calpicus, after the Latin word for the rock of Gibraltar. One scientist joked: ‘Walk up, Ladies and gentlemen, walk up! and see the ‘grand priscan, pithecoid...wild Homo calpicus of Gibraltar.’

Around this time, the little skull even met Charles Darwin. Darwin called the fossil 'wonderful' when his friend brought it by his house one Thursday in September of 1864. bit.ly/2nOt2Zw

Within a year of the announcement that the Forbes skull was an object of immense scientific importance, however, it retreated back into the shadows again, tucked into a back room of the Royal College of Surgeons, collecting dust.

The specimen languished for decades before being rescued in the 20th century and brought to its current home, the @NHM_London, where I first visited it in 2014 as it sat on display in an exhibition entitled Treasures; a somewhat ironic turn of events considering the skull’s story

It never received the name Homo calpicus, but instead is now classified as Homo neanderthalensis (a story for another day).

The specimen was found, lost, found again, and lost again, before resting in the spotlight. But what does the twice forgotten fossil teach us? It serves as a reminder, it seems to me, that timing and luck are factors in scientific discoveries.

In 1914, an anthropologist claimed that "no Neanderthal specimen has a more remarkable history." Little did he know, the story continues. The fossil is still teaching us things—this year, we finally saw the genome of the fossil: bit.ly/2Mi2jy1

And that's a tiny taste of why I find the Gibraltar Neanderthal such a fascinating specimen. Its story was not a straight line, but instead full of twists and turns—and it's not over yet.

If you want to know more about a fossil that was lost, then found, then lost again, check out my paper on the wild Homo calpicus of Gibraltar (bit.ly/2U5mCjA) or see @DrAlexMenez’s great book: Almost Homo calpicus.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh