Thread.

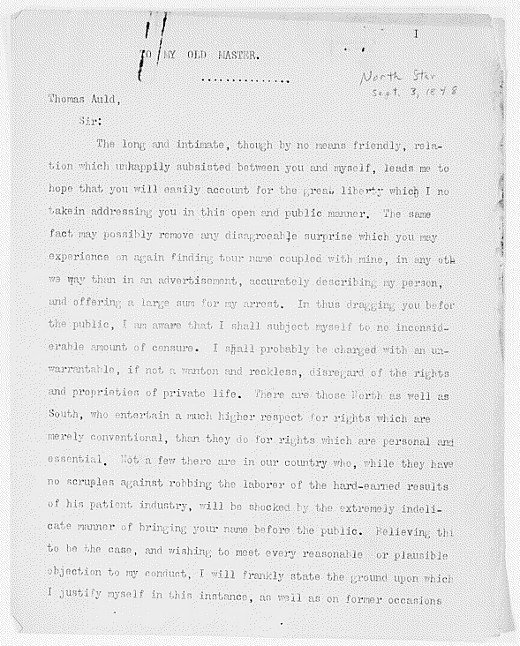

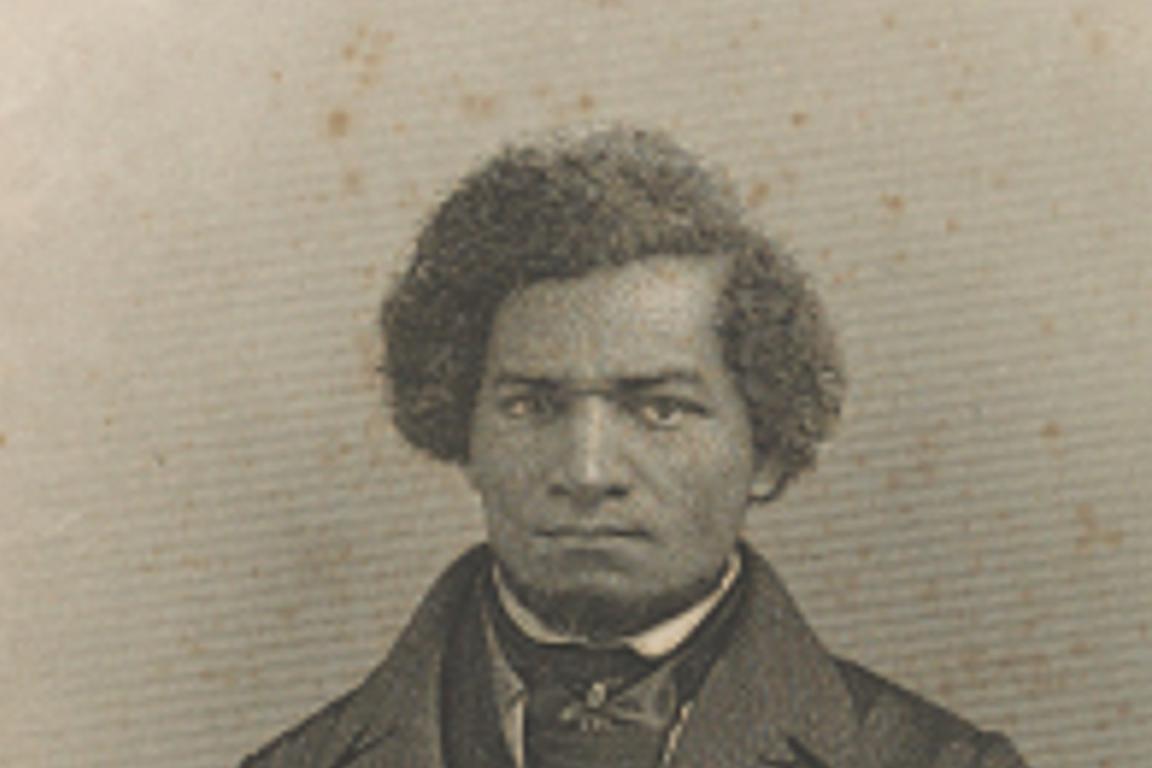

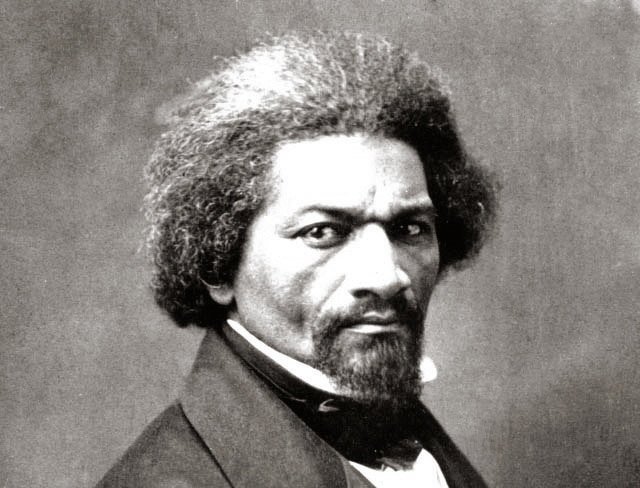

This incredible letter was written by Frederick Douglass in September of 1848, and it was addressed to Thomas Auld - a man who had been his slave master for several years:

This incredible letter was written by Frederick Douglass in September of 1848, and it was addressed to Thomas Auld - a man who had been his slave master for several years:

1) Sir:

The long and intimate, though by no means friendly, relation which unhappily subsisted between you and myself, leads me to hope that you will easily account for the great liberty which I now take in addressing you in this open and public manner.

The long and intimate, though by no means friendly, relation which unhappily subsisted between you and myself, leads me to hope that you will easily account for the great liberty which I now take in addressing you in this open and public manner.

2) The same fact may possibly remove any disagreeable surprise which you may experience on again finding your name coupled with mine, in any other way than in an advertisement, accurately describing my person, and offering a large sum for my arrest.

3) In thus dragging you again before the public, I am aware that I shall subject myself to no inconsiderable amount of censure. I shall probably be charged with an unwarrantable if not a wanton and reckless disregard of the rights and proprieties of private life.

4) There are those North as well as South, who entertain a much higher respect for rights which are merely conventional, than they do for rights which are personal and essential.

5) Not a few there are in our country who, while they have no scruples against robbing the laborer of the hard-earned results of his patient industry, will be shocked by the extremely indelicate manner of bringing your name before the public.

6) Believing this to be the case, and wishing to meet every reasonable or plausible objection to my conduct, I will frankly state the ground upon which I justify myself in this instance, as well as on former occasions when I have thought proper to mention your name in public.

7) All will agree that a man guilty of theft, robbery, or murder, has forfeited the right to concealment and private life; that the community have a right to subject such persons to the most complete exposure.

8) However much they may desire retirement, and aim to conceal themselves and their movements from the popular gaze, the public have a right to ferret them out, and bring their conduct before the proper tribunals of the country for investigation.

9) Sir, you will undoubtedly make the proper application of these generally admitted principles, and will easily see the light in which you are regarded by me. I will not therefore manifest ill temper, by calling you hard names.

10) I know you to be a man of some intelligence, and can readily determine the precise estimate which I entertain of your character. I may therefore indulge in language which may seem to others indirect and ambiguous, and yet be quite well understood by yourself.

11) I have selected this day on which to address you, because it is the anniversary of my emancipation; and knowing of no better way, I am led to this as the best mode of celebrating that truly important event.

12) Just ten years ago this beautiful September morning, yon bright sun beheld me a slave—a poor degraded chattel—trembling at the sound of your voice, lamenting that I was a man, and wishing myself a brute.

13) The hopes which I had treasured up for weeks of a safe and successful escape from your grasp, were powerfully confronted at this last hour by dark clouds of doubt and fear, making my person shake and my bosom to heave with the heavy contest between hope and fear.

14) I have no words to describe to you the deep agony of soul which I experienced on that never to be forgotten morning—(for I left by daylight). I was making a leap in the dark. The probabilities, so far as I could by reason determine them, were stoutly against the undertaking.

15) The preliminaries and precautions I had adopted previously, all worked badly. I was like one going to war without weapons—ten chances of defeat to one of victory.

16) One in whom I had confided, and one who had promised me assistance, appalled by fear at the trial hour, deserted me, thus leaving the responsibility of success or failure solely with myself.

You, sir, can never know my feelings.

You, sir, can never know my feelings.

17) (...) I embraced the golden opportunity, took the morning tide at the flood, and a free man, young, active and strong, is the result.

I have often thought I should like to explain to you the grounds upon which I have justified myself in running away from you.

I have often thought I should like to explain to you the grounds upon which I have justified myself in running away from you.

18) I am almost ashamed to do so now, for by this time you may have discovered them yourself. I will, however, glance at them.

19) When yet but a child about six years old, I imbibed the determination to run away. The very first mental effort that I now remember on my part, was an attempt to solve the mystery, why am I a slave?

20) and with this question my youthful mind was troubled for many days, pressing upon me more heavily at times than others. When I saw the slave-driver whip a slave woman, cut the blood out of her neck, and heard her piteous cries, I went away into the corner of the fence ...

21) ... wept and pondered over the mystery. I had, through some medium, I know not what, got some idea of God, the Creator of all mankind, the black and the white, and that he had made the blacks to serve the whites as slaves. How he could do this and be good, I could not tell.

22) I was not satisfied with this theory, which made God responsible for slavery, for it pained me greatly, and I have wept over it long and often.

23) At one time, your first wife, Mrs. Lucretia, heard me singing and saw me shedding tears, and asked of me the matter, but I was afraid to tell her. I was puzzled with this question, till one night, while sitting in the kitchen ...

24) ... I heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa by white men, and were sold here as slaves.

The whole mystery was solved at once.

The whole mystery was solved at once.

25) Very soon after this my aunt Jinny and uncle Noah ran away, and the great noise made about it by your father-in-law, made me for the first time acquainted with the fact, that there were free States as well as slave States.

26) From that time, I resolved that I would some day run away. The morality of the act, I dispose as follows: I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons.

What you are, I am.

You are a man, and so am I.

What you are, I am.

You are a man, and so am I.

27) God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bound to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine.

28) I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence.

29) In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me, and in no way lessened your means for obtaining an honest living.

Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner. I therefore see no wrong in any part of the transaction.

Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner. I therefore see no wrong in any part of the transaction.

30) It is true, I went off secretly, but that was more your fault than mine.

Had I let you into the secret, you would have defeated the enterprise entirely; but for this, I should have been really glad to have made you acquainted with my intentions to leave.

Had I let you into the secret, you would have defeated the enterprise entirely; but for this, I should have been really glad to have made you acquainted with my intentions to leave.

31) (...) Since I left you, I have had a rich experience. I have occupied stations which I never dreamed of when a slave. Three out of the ten years since I left you, I spent as a common laborer on the wharves of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

32) It was there I earned my first free dollar. It was mine.

I could spend it as I pleased. I could buy hams or herring with it, without asking any odds of any body. That was a precious dollar to me.

I could spend it as I pleased. I could buy hams or herring with it, without asking any odds of any body. That was a precious dollar to me.

33) You remember when I used to make seven or eight, or even nine dollars a week in Baltimore, you would take every cent of it from me every Saturday night, saying that I belonged to you, and my earnings also.

34) (...) After remaining in New Bedford for three years, I met with Wm. Lloyd Garrison, a person of whom you have possibly heard, as he is pretty generally known among slaveholders.

35) He put it into my head that I might make myself serviceable to the cause of the slave by devoting a portion of my time to telling my own sorrows, and those of other slaves which had come under my observation.

36) This was the commencement of a higher state of existence than any to which I had ever aspired. I was thrown into society the most pure, enlightened and benevolent that the country affords.

37) Among these I have never forgotten you, but have invariably made you the topic of conversation—thus giving you all the notoriety I could do. I need not tell you that the opinion formed of you in these circles, is far from being favorable.

38) They have little respect for your honesty, and less for your religion.

(...) The transition from degradation to respectability was indeed great, and to get from one to the other without carrying some marks of one's former condition, is truly a difficult matter.

(...) The transition from degradation to respectability was indeed great, and to get from one to the other without carrying some marks of one's former condition, is truly a difficult matter.

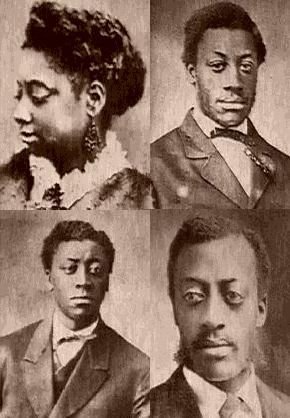

39) (...) So far as my domestic affairs are concerned, I can boast of as comfortable a dwelling as your own. I have an industrious and neat companion, and four dear children—the oldest a girl of nine years, and three fine boys, the oldest eight.

40) The three oldest are now going regularly to school—two can read and write, and the other can spell with tolerable correctness words of two syllables: Dear fellows!

They are all in comfortable beds, and are sound asleep, perfectly secure under my own roof.

They are all in comfortable beds, and are sound asleep, perfectly secure under my own roof.

41) There are no slaveholders here to rend my heart by snatching them from my arms, or blast a mother's dearest hopes by tearing them from her bosom.

42) These dear children are ours—not to work up into rice, sugar and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel—to train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can ...

43) ... to make them useful to the world and to themselves.

Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control.

Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control.

44) I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market.

45) You well know that I wear stripes on my back inflicted by your direction; and that you, while we were brothers in the same church, caused this right hand, with which I am now penning this letter, to be closely tied to my left ...

46) ... and my person dragged at the pistol's mouth, fifteen miles, from the Bay side to Easton to be sold like a beast in the market, for the alleged crime of intending to escape from your possession.

All this and more you remember, and know to be perfectly true.

All this and more you remember, and know to be perfectly true.

47) At this moment, you are probably the guilty holder of at least three of my own dear sisters, and my only brother in bondage. These you regard as your property. They are recorded on your ledger, or perhaps have been sold to human flesh mongers.

48) Sir, I desire to know how and where these dear sisters are. Have you sold them? or are they still in your possession? What has become of them? are they living or dead?

49) And my dear old grandmother, whom you turned out like an old horse, to die in the woods—is she still alive?

Write and let me know all about them.

Write and let me know all about them.

50) (...) Your wickedness and cruelty committed in this respect on your fellow-creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back, or theirs.

51) Your mind must have become darkened, your heart hardened, your conscience seared and petrified, or you would have long since thrown off the accursed load and sought relief at the hands of a sin-forgiving God.

52) (...) I will now bring this letter to a close, you shall hear from me again unless you let me hear from you. I intend to make use of you as a weapon with which to assail the system of slavery (...)

53) ... as a means of concentrating public attention on the system, and deepening their horror of trafficking in the souls and bodies of men.

54) I shall make use of you as a means of exposing the character of the American church and clergy—and as a means of bringing this guilty nation with yourself to repentance.

55) In doing this I entertain no malice towards you personally. There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant.

56) Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other.

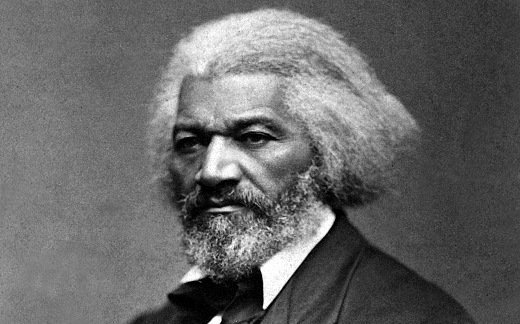

I am your fellow man, but not your slave,

FREDERICK DOUGLASS."

I am your fellow man, but not your slave,

FREDERICK DOUGLASS."

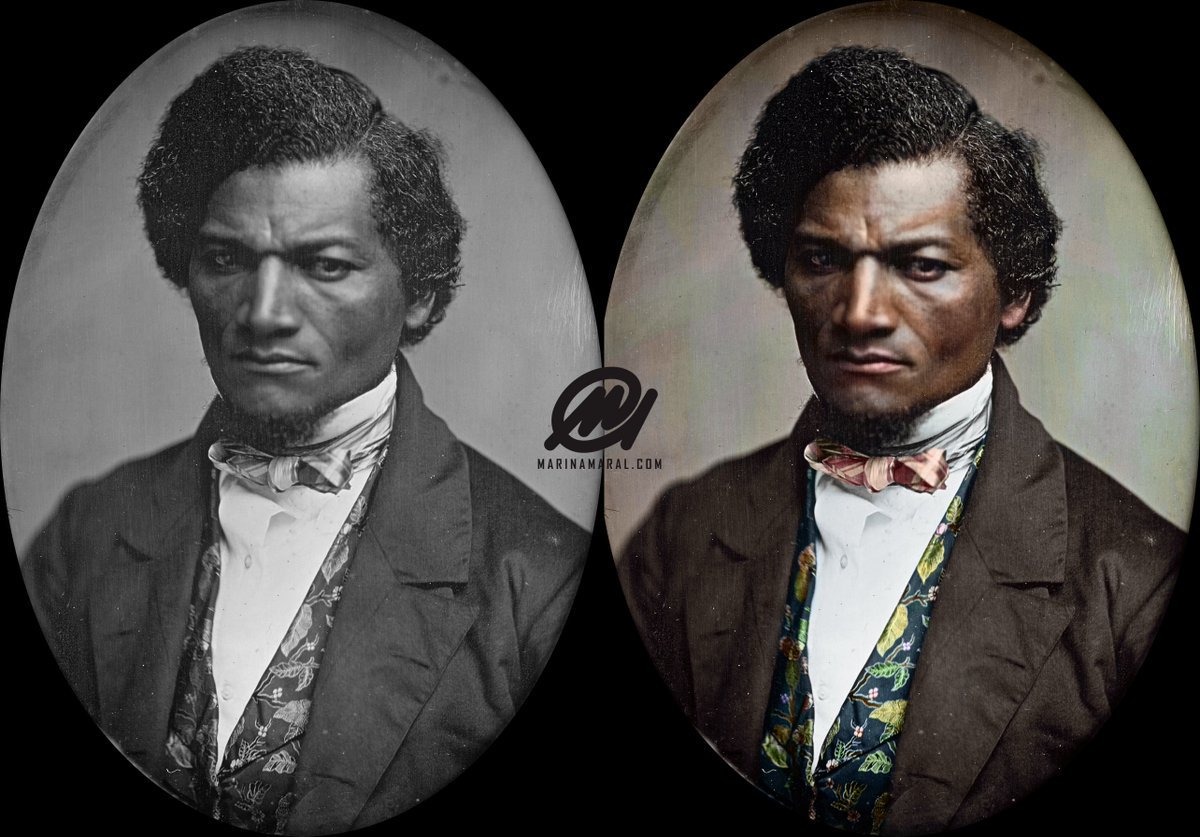

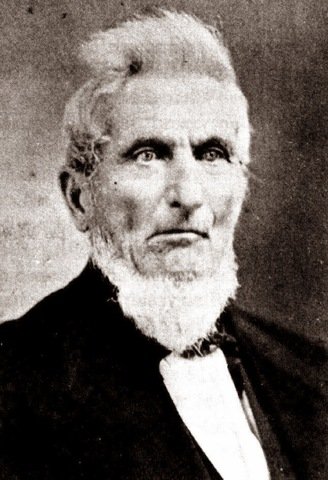

57) In 1877, near the end of Thomas's life, he and Frederick Douglass did meet again. An account of the meeting was written and published by Frederick Douglass in a newspaper.

58) "I had by my writings made his name and his deeds familiar to the world in four different languages, yet here we were, after four decades, once more face to face--he on his bed, aged and tremulous, drawing near the sunset of life ...

... and I, his former slave, United States Marshal of the district of Columbia, holding his hand and in friendly conversation with him in a sort of final settlement of past differences preparatory to his stepping into his grave ...

... where all distinctions are at an end, and where the great and the small, the slave and his master, are reduced to the same level."

59) "Hearing myself called by him "Marshal Douglass," I instantly broke up the formal nature of the meeting by saying, "not Marshal, but Frederick to you as formerly."

We shook hands cordially, and in the act of doing so, he, having been long stricken with palsy...

We shook hands cordially, and in the act of doing so, he, having been long stricken with palsy...

60) ... shed tears as men thus afflicted will do when excited by any deep emotion...

After he had become composed I asked him what he thought of my conduct in running away and going to the north.

After he had become composed I asked him what he thought of my conduct in running away and going to the north.

61) He hesitated a moment as if to properly formulate his reply, and said: "Frederick, I always knew you were too smart to be a slave, and had I been in your place, I should have done as you did."

62) I said, "Capt. Auld, I am glad to hear you say this. I did not run away from you, but from slavery; it was not that I loved Caesar less, but Rome more."

63) Before I left his bedside Captain Auld spoke with a cheerful confidence of the great change that awaited him, and felt himself about to depart in peace."

END

END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh