I'm a specialist in the destruction of art during war, and I know that Trump's targeting of #IranianCulturalSites wouldn't just be a clear war crime... it wouldn't even work. A thread.

https://twitter.com/artcrimeprof/status/1213865718908903424

Destruction of cultural sites increases the resistance of enemy troops, cuts off the possibility of cooperation from civilians, and exponentially multiplies the difficulty of reestablishing peace.

Cultural destruction is a good tactic only for insurgents, like the Islamic State, who want a low-risk way to clear territory by frightening civilians + cutting their ties to their homes, so they flee/become refugees.

Or maybe, like the Nazis, you're aiming for genocide, and want to destroy both a population and any traces of their culture. E.g., the Nazis destroyed huge amounts of Polish and Russian cultural sites, like 85% of historic Warsaw.

But if you want to wage war against an enemy army instead of an entire population, and you want the area to recover politically and economically after the conflict is over, destroying culture is a sure way to fail.

We learned this lesson the hard way. During the Iraq War, Coalition forces were blamed for preventing the looting of the Bagdad Museum (nytimes.com/2009/02/24/wor…) and for damaging the site of ancient Babylon by turning it into a military camp (nytimes.com/2005/01/16/wor…).

Actions like these reduced trust from local populations and gave propaganda talking points to the enemy.

And peace is exponentially harder to achieve if cultural sites have been destroyed. Civilians who can no longer make a living in hotels/restaurants/other business that depended on the flow of tourists to a destroyed site are more likely to become disaffected/turn to insurgency.

For these very reasons, late last year the Army launched a new initiative to train museum directors, curators, and archaeologists, among others, as commissioned officers of the Army Reserves to be deployed to war zones to secure cultural heritage. nytimes.com/2019/10/21/art…

Respecting culture wins wars. And as those who have stooped to the deliberate destruction of cultural monuments have learned, the more important these monuments are to their cultures, the greater the chance that they will rise again.

The shrines, mosques, and ancient sites destroyed by the Islamic State have were recreated digitally almost as soon as the bombs exploded: nytimes.com/2017/02/15/art…

The historic center of Warsaw, methodologically destroyed by the Nazis with explosives and flamethrowers as part of a planned Germanization of Poland, has been meticulously reconstructed: whc.unesco.org/en/list/30/

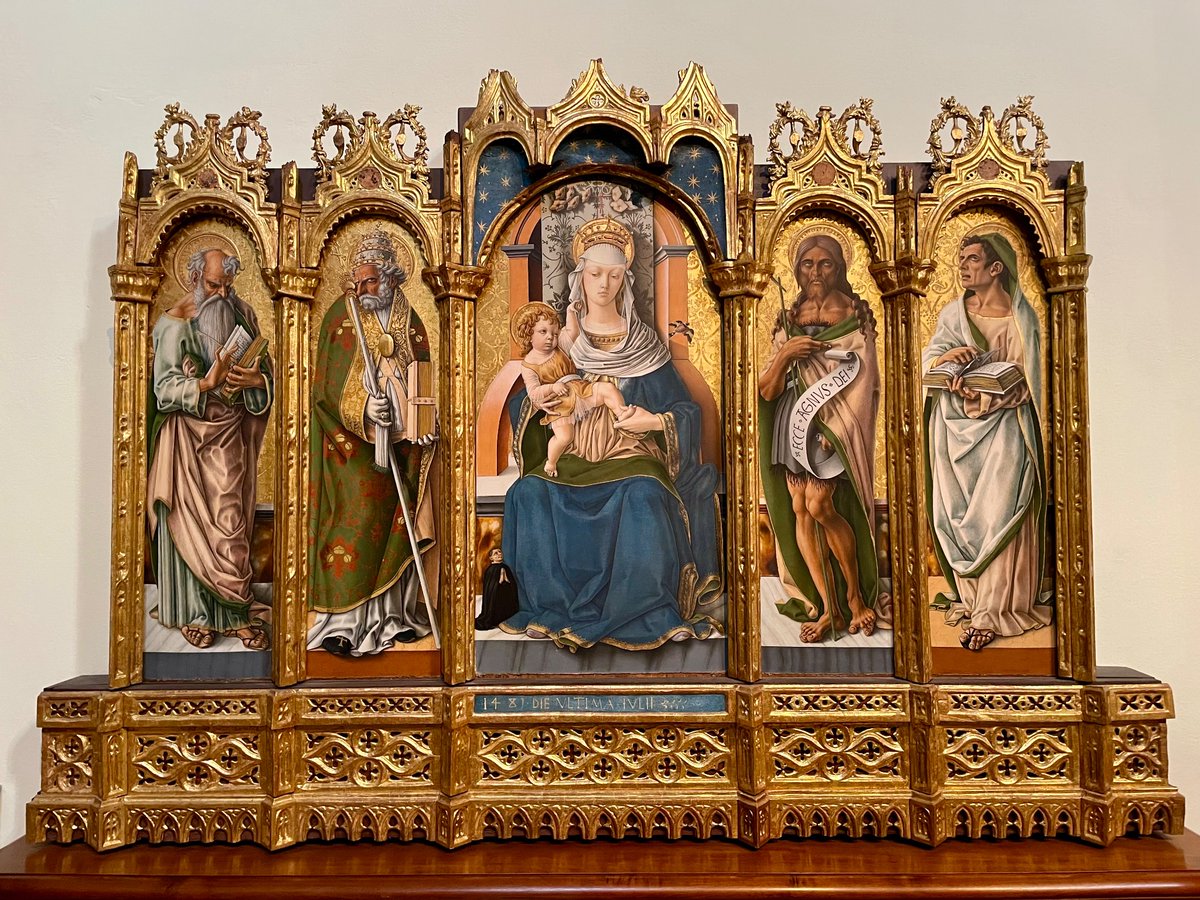

Malians rebuilt shrines destroyed by jihadists: theguardian.com/world/2016/feb…

PS, the Islamic extremist Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi is currently serving a nine year sentence for smashing these centuries-old shrines in the name of Al Qaeda - the International Criminal Court convicted him as a war criminal: nytimes.com/2017/08/17/wor…

There's universal agreement that the deliberate destruction of cultural property during conflict is a war crime. Not because all those flinty-eyed war hawks who wrote the law are secretly dedicated museum-goers. It's because destroying culture is a really good way to lose a war.

Just a reminder that this is the same administration that has already defended burning art as a war tactic (when justifying destroying art made at Guantánamo, even if by detainees who are being released): nytimes.com/2017/11/27/opi…

My op-ed on this, now out at @TheCrimeReport: thecrimereport.org/2020/01/07/mem…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh