The past is complicated. So is the present. Reading in @nature on the Shum Laka aDNA: Archaeological samples in a colonial museum used to argue that today's population of Cameroon are not descended from past peoples in the area. doi.org/10.1038/s41586…

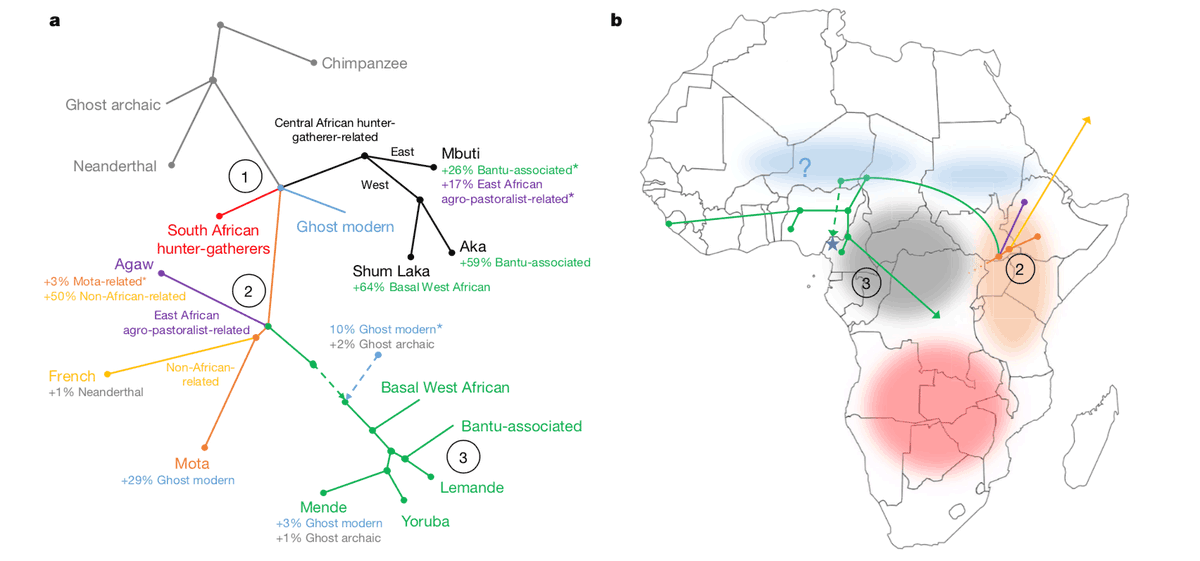

The authors emphasize discontinuity in their overall interpretation, yet data show substantial evidence of some population continuity both regionally and locally. Small fractions of ancestry from "ghost" groups are highlighted, but small fractions from modern groups downplayed.

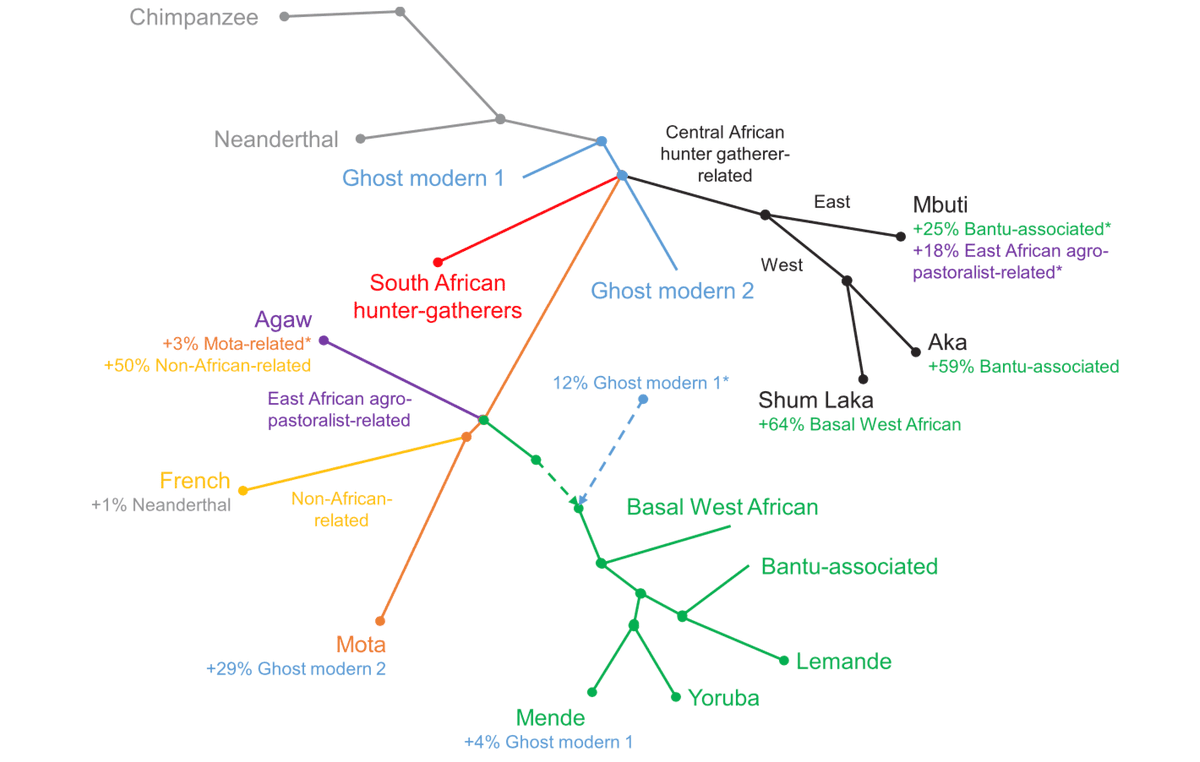

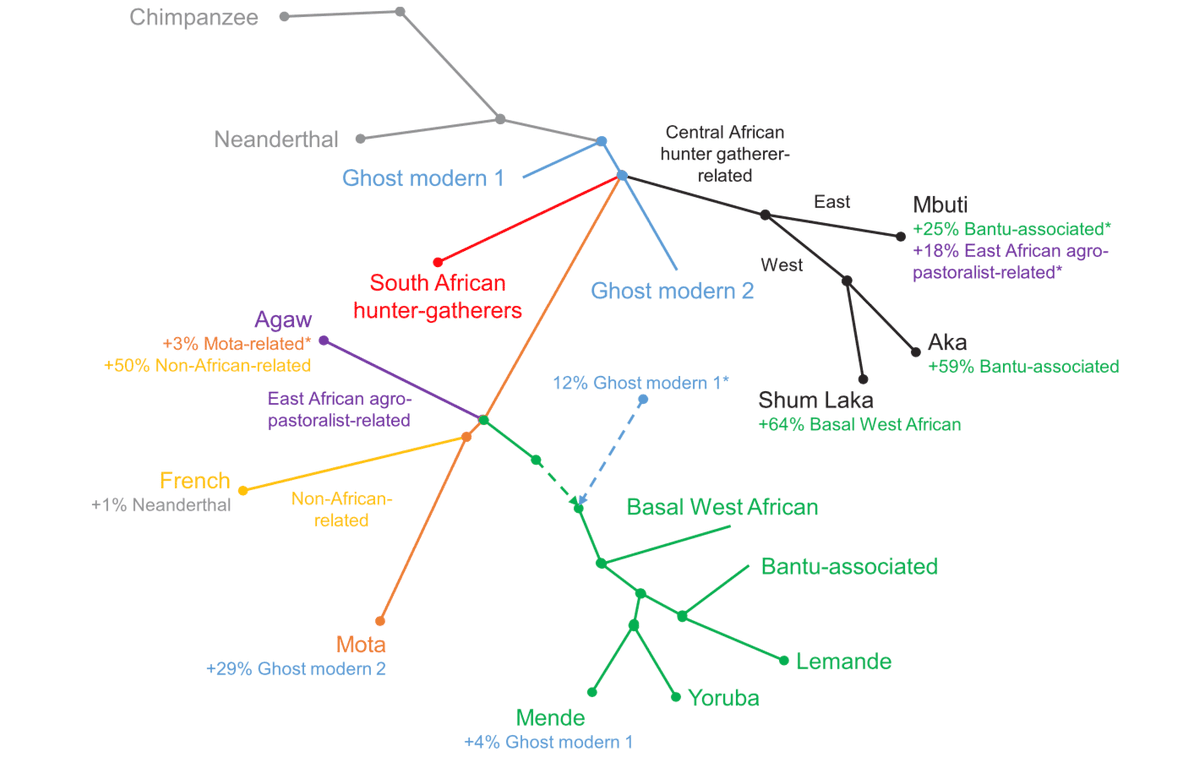

I'm fascinated by the concept of a tree seeming to show groups a part of a pure history of divergence, yet each group shows most of its heritage came from elsewhere in the tree. Shum Laka appears as a pure representative of an ancient group, with 64% from some other group.

The obvious question is why would you illustrate the 36% as the main pattern determining the place in the tree, instead of the 64%? In addition to the old unanswered question: What are these "basal" ancestry components if not a statistical artifact?

My thought today is that the contemporary and historical political complexity, and the unanswered questions about the models, are now the interesting and challenging scientific issues. Deeply redacted SNP samples of ancient genomes are not getting at these questions.

Also, why the heck is it "ghost modern" and not "basal modern". And don't these geneticists know that "basal" is a no-no term in phylogenetics?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh