I've been on the fence about the climate divestment movement for several years, but this @newrepublic story about @Stanford from @BenFranta clarified the stakes for me. 1/20 newrepublic.com/article/158086…

Over the years, many of my best students have been leaders in the divestment movement. I've focused, instead, on the design and implementation of government climate policies. But those two worlds are crashing together. 2/20

If I've learned one thing, it's that the story university elites tell about their relationship with incumbent industries bears almost no relationship to what those companies do in the real world. Behind every high-minded energy seminar is a torrent of lobbying money. 3/20

At the same time, any path to deep decarbonization will require many incumbents to completely re-tool their industries to focus on climate solutions, not simply go out of business. Trillions of dollars of capital needs to be deployed in short order. 4/20

Some seriously hope that climate-minded shareholders will help drive accountability during that transition. I know that answer doesn't satisfy my activist students, however, in no small part because there are few signs of success anyone can point them to. 5/20

I also find myself in the middle of the sponsored research debate. Big Oil's influence over university research agendas is alarming. At the same time, it's not clear to me that it's better for universities to refuse to engage with all incumbents on climate solutions. 6/20

.@BenFranta takes a harder line on shareholder activism and research funding than I do, and not without reason. (Ben, let's find a time to talk about this. I think there's a lot more nuance here than you've acknowledged.) But I'm not here to push back. 7/20

Rather, I mention my discomfort with parts of Ben's argument because I think he makes a point that's so powerful it should convince others who don't share all of his views to reconsider divestment. He's pushed me to think in a different way. 8/20

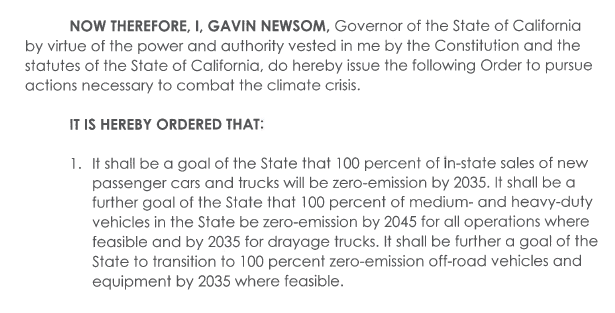

Here's one of the Stanford Deans making the case that divestment would put university research funding at risk: 9/20

I earned two of my degrees @StanfordEarth, which depends heavily on funding from the oil industry. So while I appreciate the Dean's concerns, the fact that he and other faculty members react in fear on this issue is all the reason I need to support divestment. 10/20

Faculty members' fear of the consequences of taking a political position on climate shows, unequivocally, that the funding they get from incumbent industries comes with too many strings—whether explicit or implicit. 11/20

(By the way, the @StanfordDaily has been killing it on this and so many other controversial topics on campus.) 12/20 stanforddaily.com/2020/05/28/not…

Anyway tl;dr, climate policy is complicated, academia is fraught, and broad-based fear of taking a position that is contrary to funders' economic interests demonstrates that the Stanford community has crossed a line. 13/20

Let me also acknowledge my own biases here. 12 years ago I worked for the Program on Energy and Sustainable Development, last year I got a grant from the Precourt Institute for Energy, and my PhD advisor runs the Energy Modeling Forum. 14/20

I'm proud of the work I've done at Stanford as a student climate activist, as a former research employee, and now as an adjunct faculty member. Part of the reason is that I've never been afraid of the political consequences of my work. Some of my colleagues clearly are. 15/20

I'm a pluralist at heart on these issues, perhaps because I've found it impossible to do serious and ambitious climate work when the research community has a single bright line rule—whether that's "all oil money corrupts" or "don't criticize California policymakers." 16/20

I would also encourage my friends who support the divestment movement to think about how other industries in the climate space—including the carbon offsets lobby and its environmental NGO sponsors—have operated in a way that is similar to Big Oil. 17/20

Point is that I sincerely believe the climate community needs to prioritize nuance and I'm reluctant to join this imperfect (but important) political movement. That decision is now clear for me, thanks in no small part to Ben. 18/20

https://twitter.com/BenFranta/status/1266238153204985857

Also, I am now realizing a lifelong dream: having a former (and amazing!) student change my mind. I am truly an Old. Please come to my office hours to hear stories about the Waxman-Markey bill, the Clean Development Mechanism, or the rise and fall of progressive rock. 19/20

The kids are alright. 20/20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh