Just over a year ago, @PdxInteractive released the grand strategy game "Imperator Rome". Because I have nothing better to do on a Thursday, I decided to make a THREAD dedicated to how South Arabia is represented in this game (1/n)

As the title implies, the game focuses on the rise of Rome and starts some decades a/Alexander's death and the rise of the Diadochi kingdoms in the Mediterranean and Middle-East in 304 BCE. Like most Paradox games, there are a MASSIVE amount of factions, between Britain and India

This is what the Arabian Peninsula looks like. My impression is that most of the factions here are based on Greek and Latin descriptions of the region, with some areas "painted in", with some areas being rather unhistorical (e.g. Thamud) @Folk_Kootstra might know more about this?

Let's look at South Arabia more specifically. Seeing how the game is set in 304 BCE, the most egregious problem is the presence of Himyar. The Himyarites came into being at the end of the 2nd century BCE, 200 years after the start of the game.

The area called "Himyar" should in fact probably be split between Saba and Qataban. In the reddit thread I suggested having the Himyarites appear when certain in-game conditions are met.

One of the other things that could be improved is the representation of the mountainous areas of Southwest Arabia. One of the major reasons why large-scale farming & urbanization was possible was due to the rainfall made possible by the Sarawāt and Haraz mountain ranges.

In-game, this doesn't really shine through. The highest mountains in Yemen are over 3 000 meters high, but the game kind of makes it look like a minor highland. Compare Southwest Arabia to the Apennines in Italy and the Zagros in Western Iran.

Speaking of urbanization, another thing that stands out is the lack of cities in South Arabia. Of course we don't have the same data as for Greek and Roman cities, but there were massive urban centers in Yemen, at least according to Strabo.

Speaking of cities! Right now the capital of Saba isṢanʿā (which should really be Ṣanʿaw or sth like that), but at this period it should be Mārib. I'd really like to see that changed in a future update.

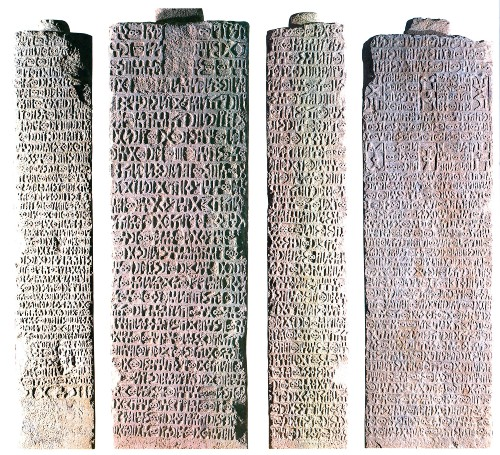

There are also some ways to add more flavor: a great idea would be have a game mechanic for the Marib dam, including its maintenance/repair/restoration. Keeping the dam in proper order was both politically and religiously important for the rulers of South Arabia.

The game could represent this by having players choose whether or not to invest in maintaining and/or repairing the dam at certain intervals, with potentially catastrophic results if they choose to ignore it.

A final suggestion I would make (for now) would be to replace the Latinate names of South Arabian locales with their (reconstructed) forms. So instead of Emporion we'd get Makhā, instead of Felicita we could go with Qaniya(t), and Mariaba should of course be Marib.

Anyway, I'd recommend everyone to try out the game. It's a lot of fun and despite my nitpicking, it feels really great to restore the Kingdom of Saba to include all of South Arabia and to enact revenge on Aksum. Would recommend, 10/10.

Oh, and before I forget: a link to the subreddit thread, where I go into some more details: reddit.com/r/Imperator/co…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh