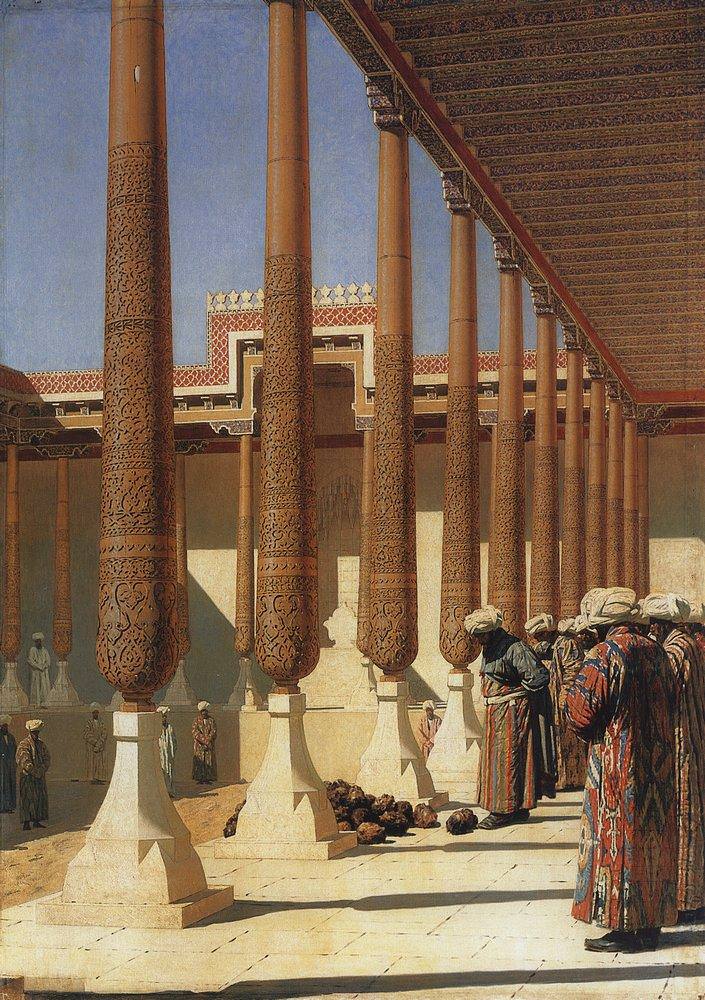

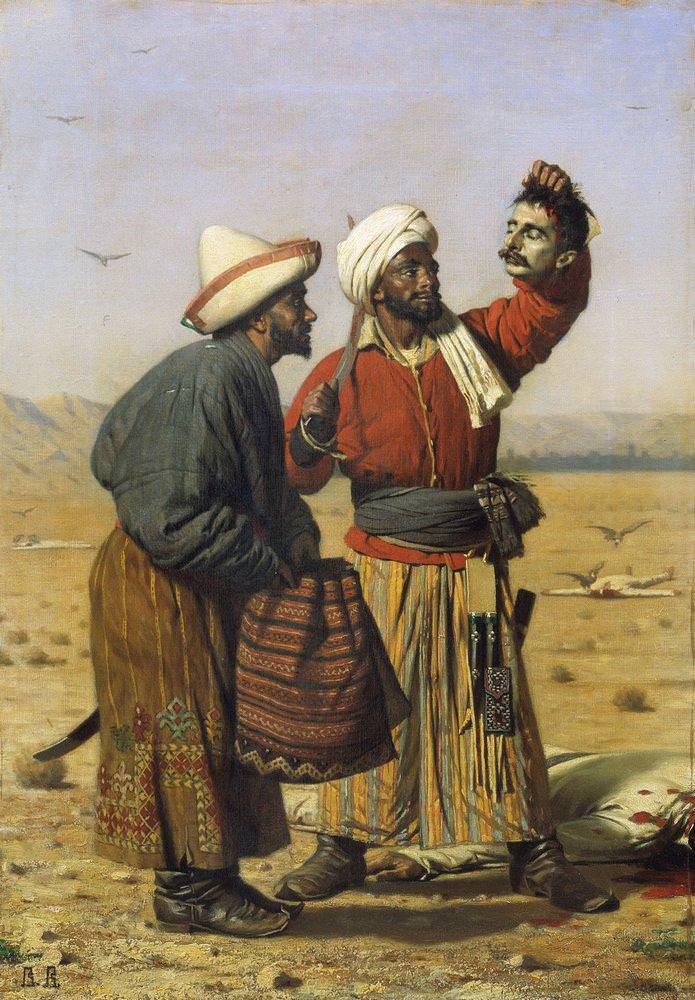

“To all great conquerors, past, present and to come.”

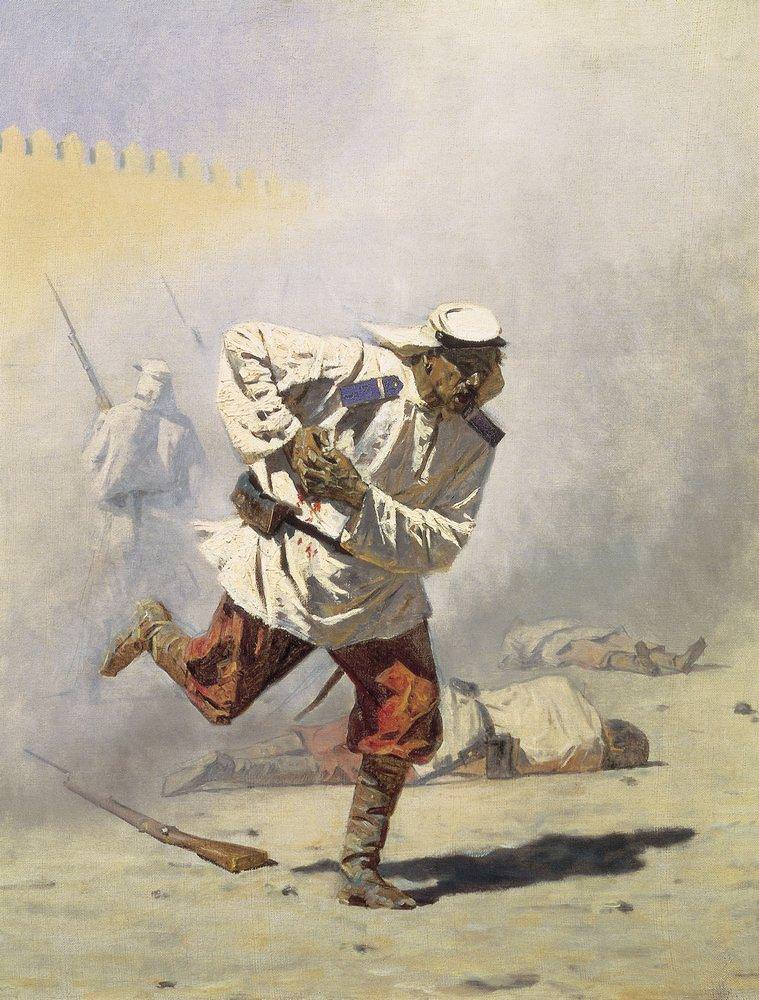

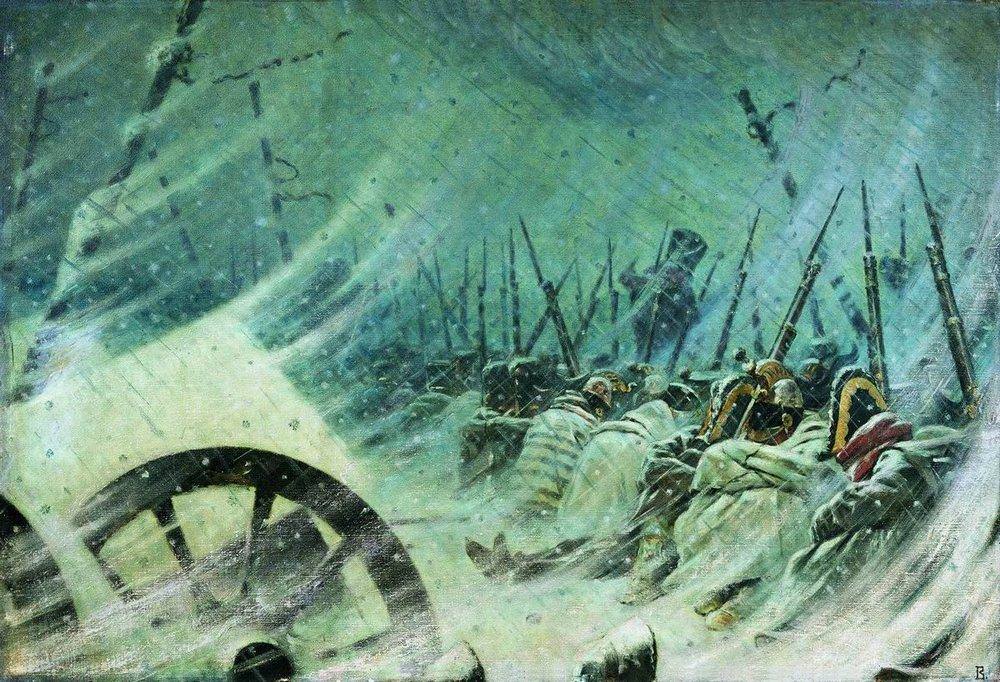

“I have seen a priest performing the last religious rites on a battle-field over a mass of killed, plundered, mutilated soldiers..."

ugh sorry

artchallenge.ru/gallery/en/47.…

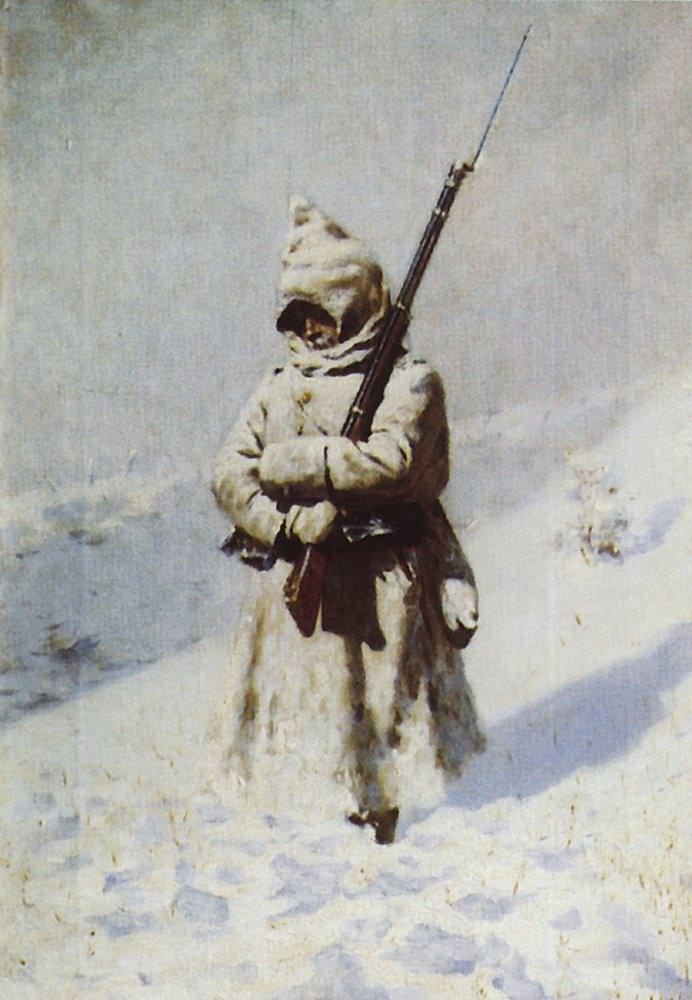

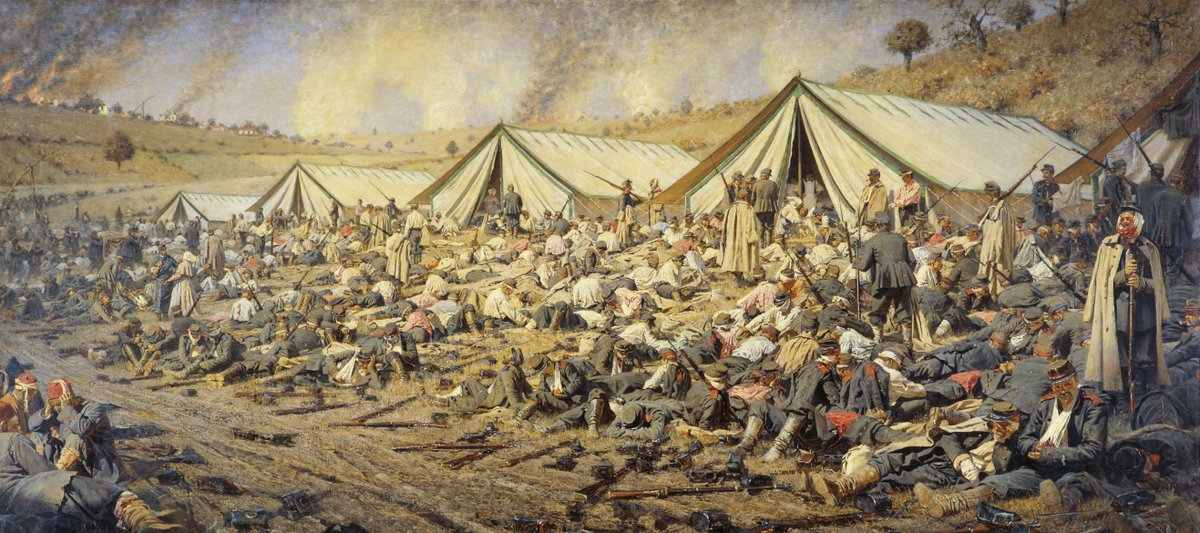

Take, for example, the 1877 Battle of Shipka Pass, which Vereshchagin witnessed firsthand, during the Russo-Turkish War - in which the artist's own brother was killed.

For them, it is an iconic event on a par with the “300 Spartans” at Thermopylae, or the 20th Maine at Gettysburg.

A few years ago, I even documented an anti-immigrant militia that draws its name from the event: nbcnews.com/storyline/euro…

Thanks so much for reading!

except drive the car to a super sketchy place to encounter a self-described "Bulgarian special boy" and his rifle

so the weird grammatical errors and mistakes (“dress jogging” ugh) are the result of this

and yes i know he was technically a field marshal

feel free to say hi

What is a painting or other work of art that has moved you or challenged your beliefs? And why?