After graduation he built radios for government troops in China's interior.

When the communists gained control of China, he decided not to return.

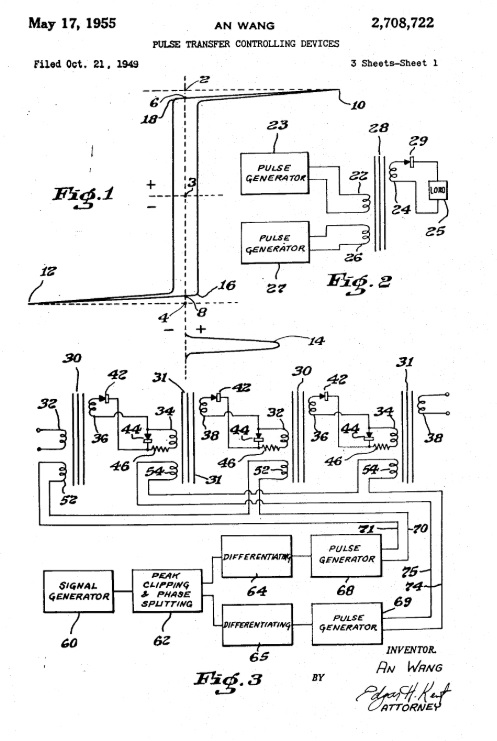

Due to Harvard's policy at the time, Wang could patent and own his invention, the pulse transfer controlling device.

patents.google.com/patent/US27087…

He contacted anyone who might need memory cores and slowly built orders.

IBM incorporated the memory core in its new line-up of computers and when Wang's patent was issued in 1955, they opened negotiations.

Wang accepted $400k cash and a contingent payment of $100k

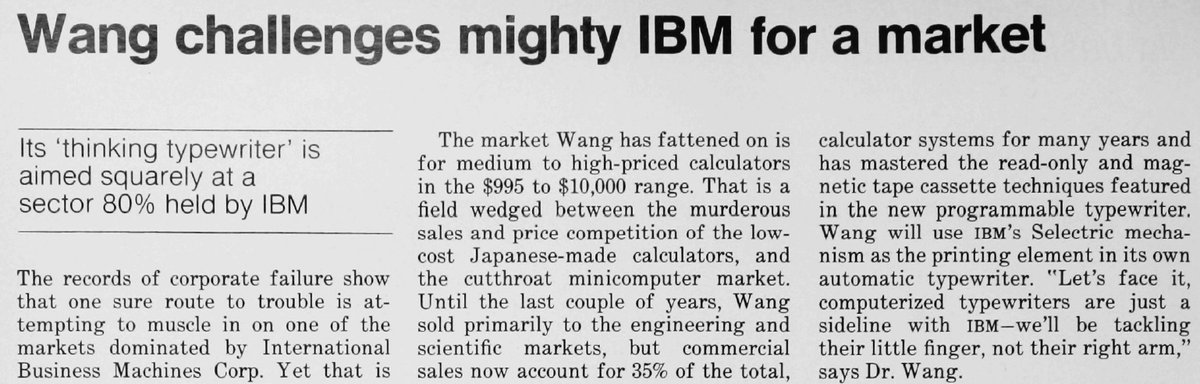

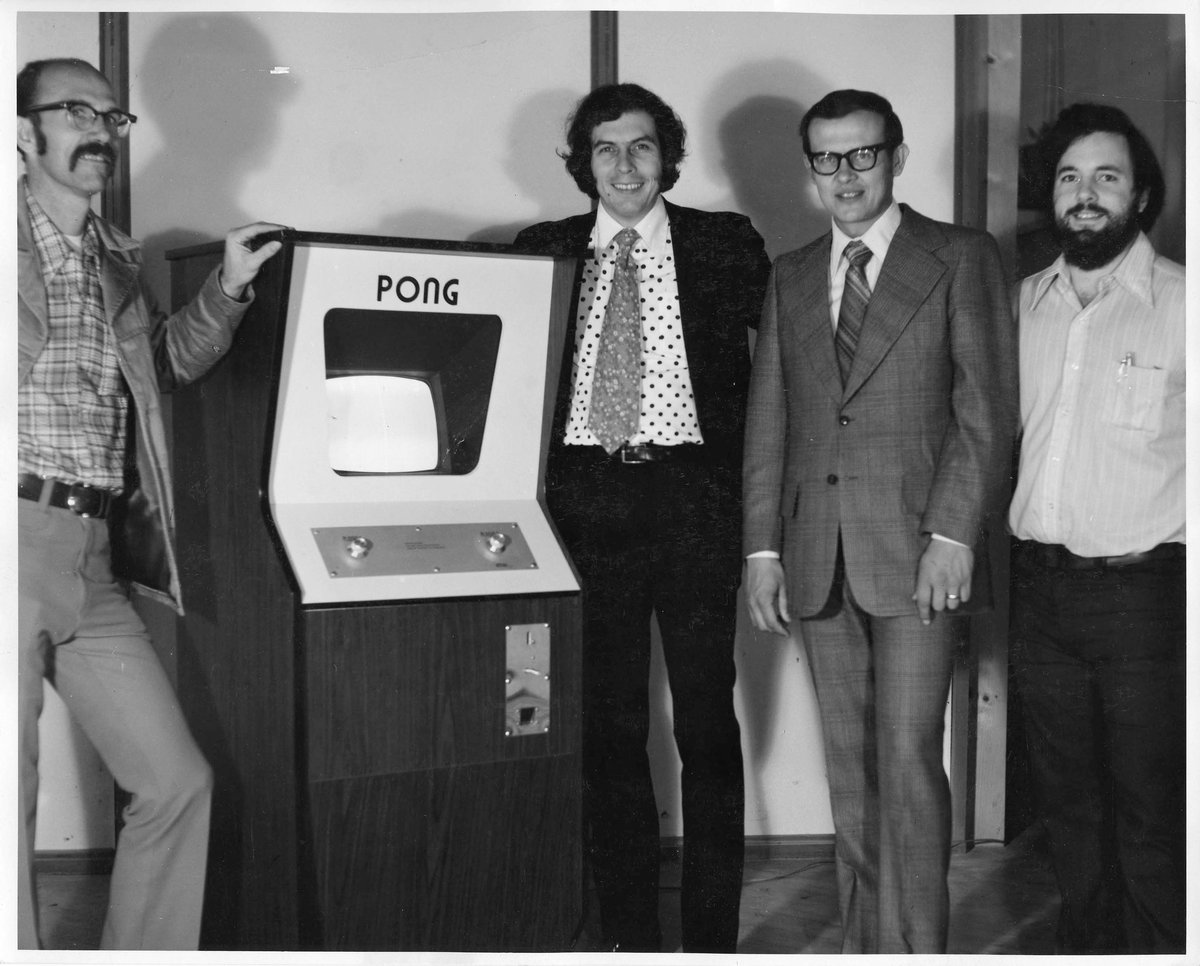

He was also surprised by IBM's slow pace and became convinced that faster, more nimble firms could compete against the corporate giants.

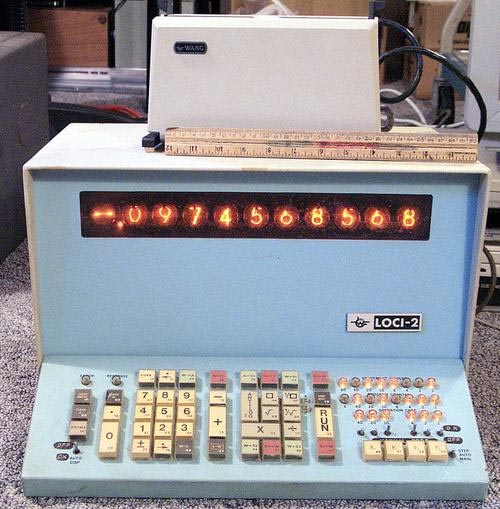

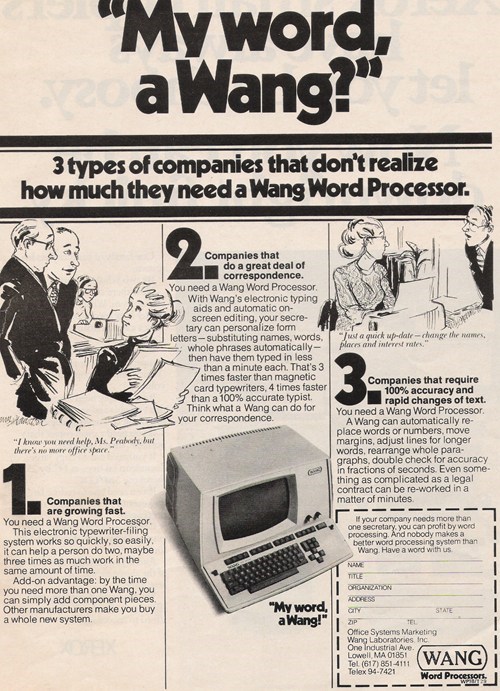

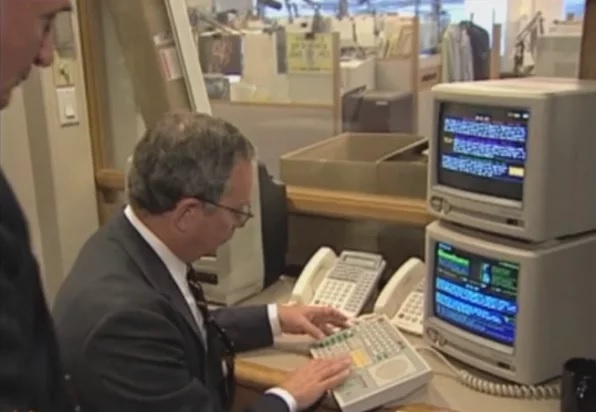

80% of the largest 2,000 US companies owned Wang equipment

"Nobody is hungrier than Wang!"

Brand recognition among managers jumped from 4% to 80%.

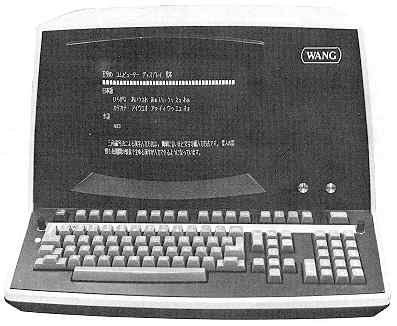

"Wang: we're gunning for IBM"

Even for the 80's that was a bit outrageous.

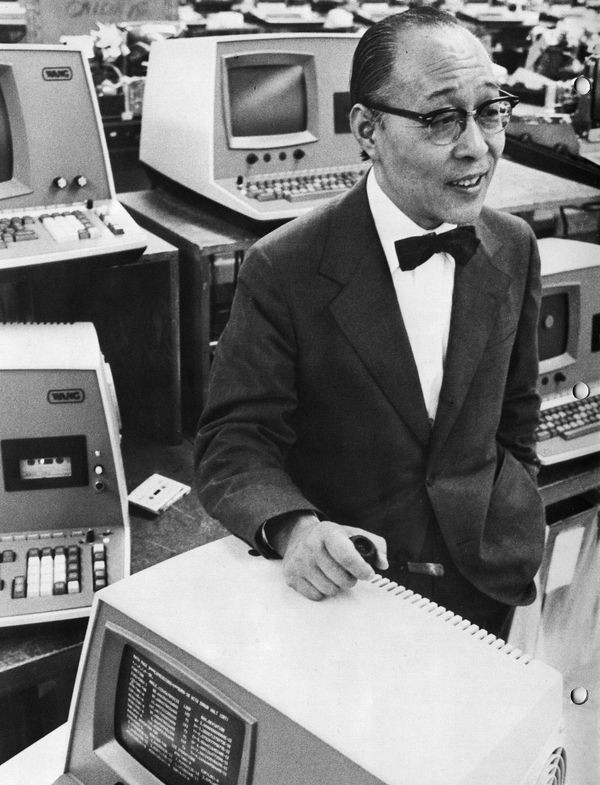

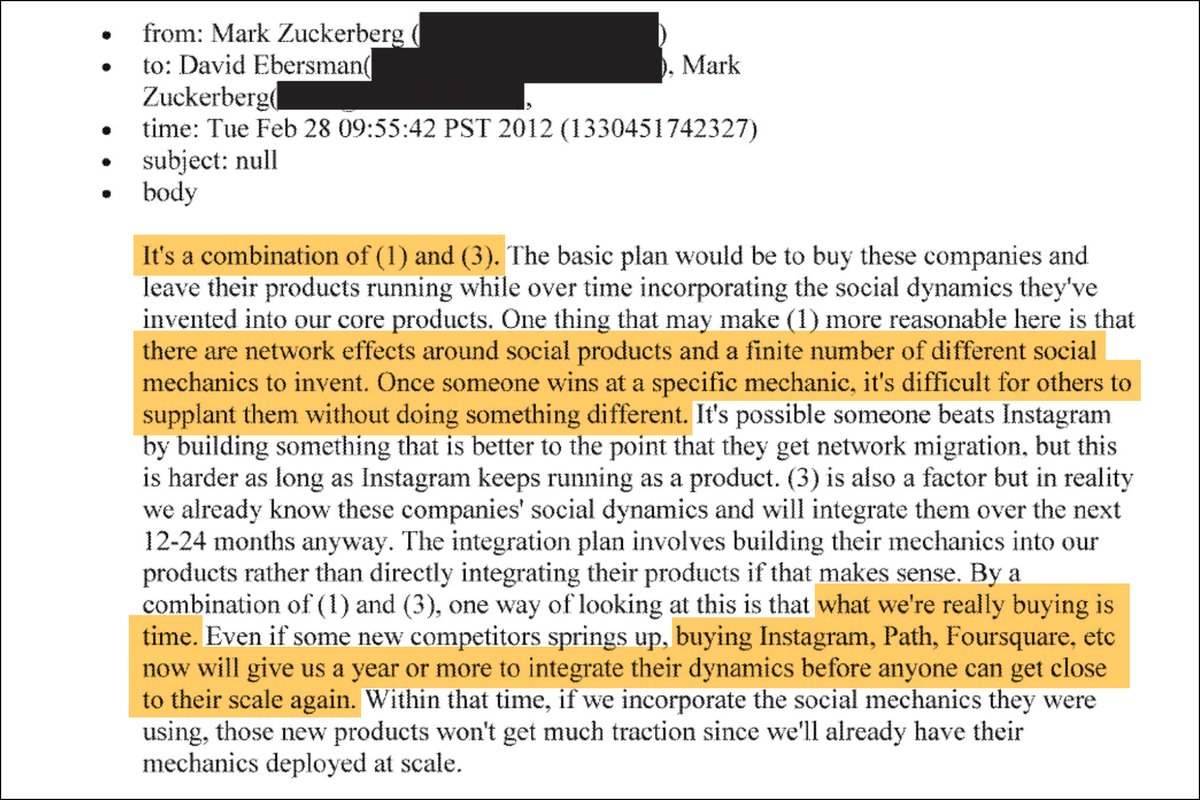

He was still obsessed with IBM and kept a chart with the growth of both firms. In the 1990's, he believed, his firm would overtake them.

Fred realized this and announced a line-up of 14 new products. But most of them were vaporware.

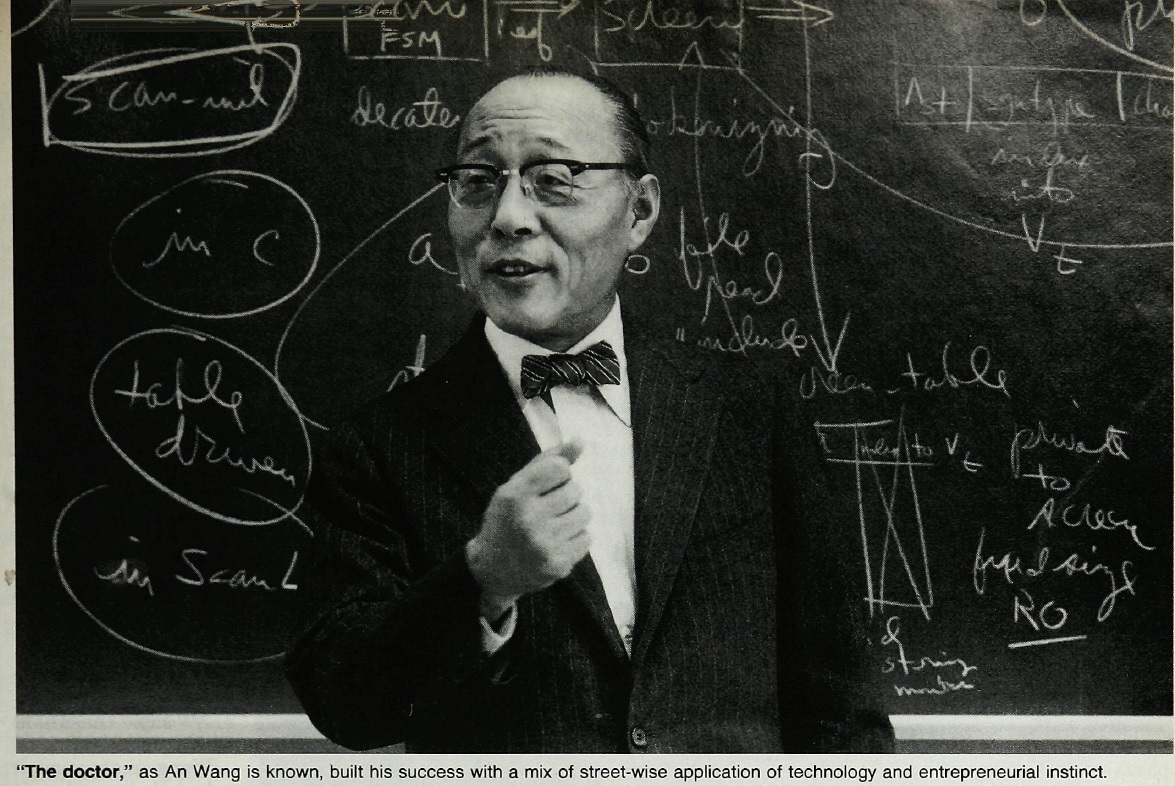

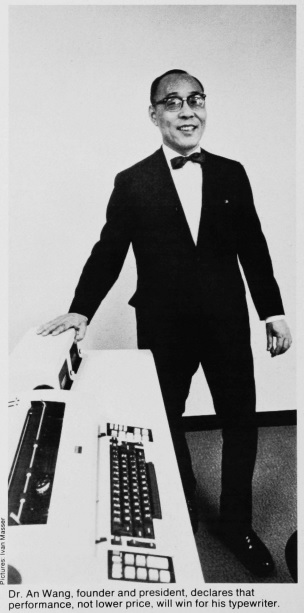

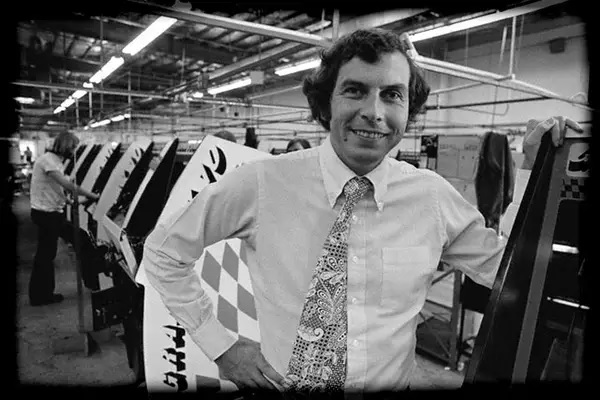

Dr. An Wang.

This time, the Doctor had missed the revolution.

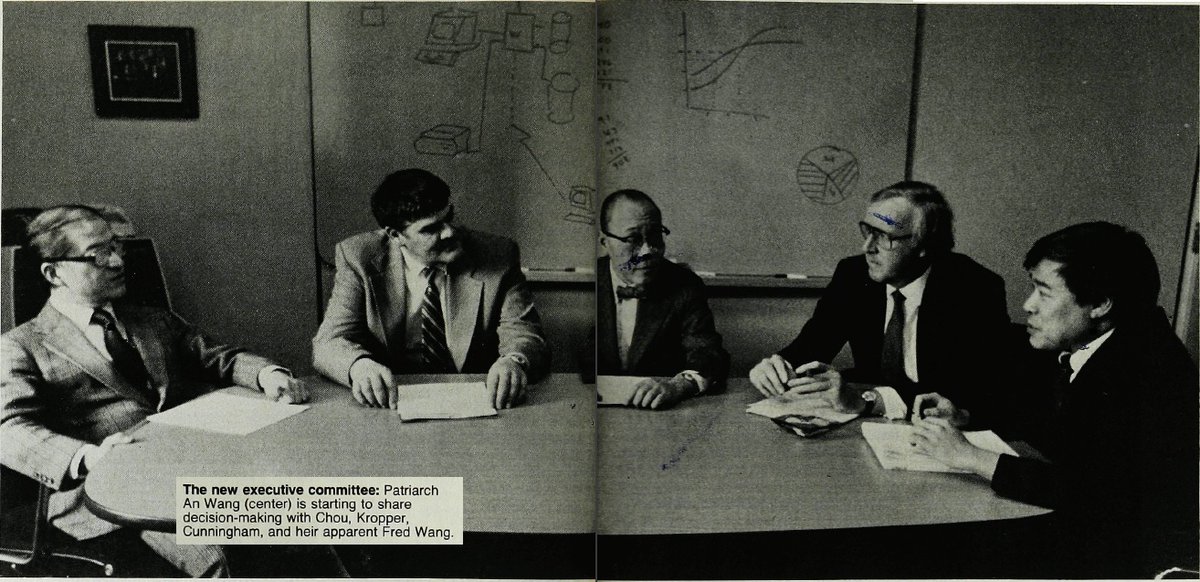

"All other things being equal, my children should be more highly motivated than a professional manager because of their substantial ownership."

"He is my son. He can do it," he told skeptical board members and employees.

Wang was careful to retain control and had dual share classes that gave him more voting power.

Back from the hospital, Wang fired his son who accepted the decision stoically.

"It was a very difficult decision. I am sorry," Wang told him.

He would pass away from cancer in 1990. Wang Laboratories filed for bankruptcy in 1992.

"The geniuses seldom build great management teams, for the simple reason that they don't need one, and often don't want one. When the genius leaves, the helpers are often lost."

Despite his Icarus-like fall, it is worth remembering how much he achieved. Nobody thought he would reach the pinnacle of business in the first place.

"I founded Wang Laboratories... to show that Chinese could excel at things other than running laundries and restaurants."

He sure did.

The auctioneer wanted to start bids at $3mm but "the silence was deafening"

So instead he started at $100,000. The final bid was only $525,000. Sold.

"You have to risk failure to succeed. The important thing is not to make one single mistake that will jeopardize the future."

"Success is more a function of consistent common sense than it is of genius."