The Bashkir language is spoken by the Bashkirs (no shit), a Turkic people who predominantly live in contemporary Central Russia.

Their words for "straw" and "pencil" are related, but ended up in Bashkir in very different ways. Time for another weird etymology!

Their words for "straw" and "pencil" are related, but ended up in Bashkir in very different ways. Time for another weird etymology!

These words are halam and kələm respectively. Look pretty similar right? Let's start with the latter.

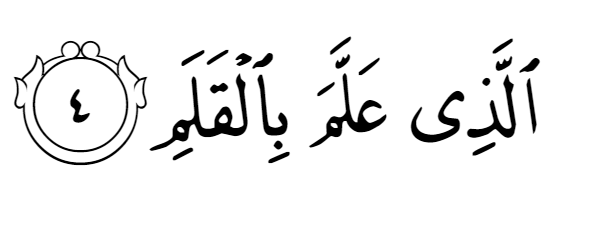

Kələm ended up in Bashkir through an Iranic language or directly from Arabic, where it means a writing tool. The Quran says God "taught men by the pen" (qalam)

Kələm ended up in Bashkir through an Iranic language or directly from Arabic, where it means a writing tool. The Quran says God "taught men by the pen" (qalam)

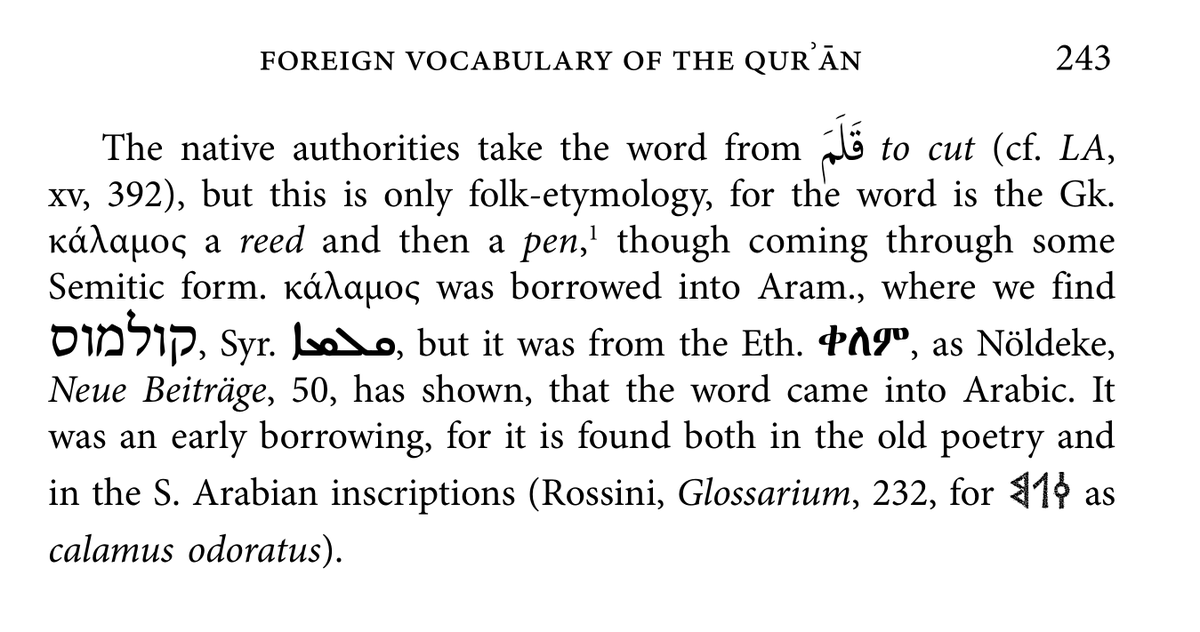

However, there is an interesting story behind this word. The famous scholar Theodor Nöldeke pointed out that qalam is a Greek loanword, from kalamos. Jeffery (below) agrees with him, suggesting that the word probably entered Arabic through Ge'ez, an Ethiopic language.

The Greek word, however, goes back to an Indo-European root *ḱl̥h₂mos, whose descendants we find as Latin culmus, Germanic *halmaz (whence also English ha(u)lm) and Slavic *solma. These all mean "straw".

Sometime after Bashkiria was annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th century, the Russian word for straw солoма (soloma) found its way into the Bashkir language. Typical for Bashkir is tyrbubg word-initial s > h (e.g. Tatar süz, Bashkir hüz). This is why we get halam.

So there you have it! The originally Indo-European word for "straw" found itself into the Turkic Bashkir language through both Slavic and Semitic detours.

Happy weekend!

Happy weekend!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh