Some ideas about OZYMANDIAS, by Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1818.

1) I met a Traveller from an antique land

Shelley began writing Ozymandias after the British Museum acquired a statue of that figure (Ramesses II). It’s important that this poem describes a statue *in situ*...

1/

1) I met a Traveller from an antique land

Shelley began writing Ozymandias after the British Museum acquired a statue of that figure (Ramesses II). It’s important that this poem describes a statue *in situ*...

1/

Not in a museum. The framing device allows for a reading of the statue in its original location.

An important theme of the poem is how meaning is made and changes: the meaning of the statue is different if you see it in the desert, and different to what Ozy himself intended.

2/

An important theme of the poem is how meaning is made and changes: the meaning of the statue is different if you see it in the desert, and different to what Ozy himself intended.

2/

We don’t really use the word “antique” as an adjective in everyday speech now. It means old, but it means more than old I think. Shakespeare uses the word specifically to reference the classical world, the ancient past, and I think it has that meaning here too.

3/

3/

There’s a deliberate warning of time going on here: the land itself is “antique”, but the traveller has seen the statue thousands of years after its construction and the downfall of Ozymandias’ domain. We’re being taken out of “historical” time with clear chronology...

4/

4/

And into a vaguer realm more associated with myth.

2) Who said, “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

This line has been nagging at my English senses and I think I know why. The arrival of the statue is syntactically backward. I’ll try to explain what I mean:

5/

2) Who said, “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

This line has been nagging at my English senses and I think I know why. The arrival of the statue is syntactically backward. I’ll try to explain what I mean:

5/

The ”natural” way of describing the scene would be to describe the desert first:

“In the desert, a huge statue stands, with two vast legs of stone but no trunk.”

Shelley reverses that, delaying the sense of the line until the end.

6/

“In the desert, a huge statue stands, with two vast legs of stone but no trunk.”

Shelley reverses that, delaying the sense of the line until the end.

6/

Two — two what?

Two vast — two vast what?

Two vast and trunkless — that’s even less clear

Two vast and trunkless legs — ok...

Two vast and trunkless legs of stone — GOTCHA.

7/

Two vast — two vast what?

Two vast and trunkless — that’s even less clear

Two vast and trunkless legs — ok...

Two vast and trunkless legs of stone — GOTCHA.

7/

Remember: that warping of time from line 1, and the theme of making and changing meaning. We don’t start off seeing this scene with the statue in its entirety; we have to make the journey to its antique realm along with the poem.

8/

8/

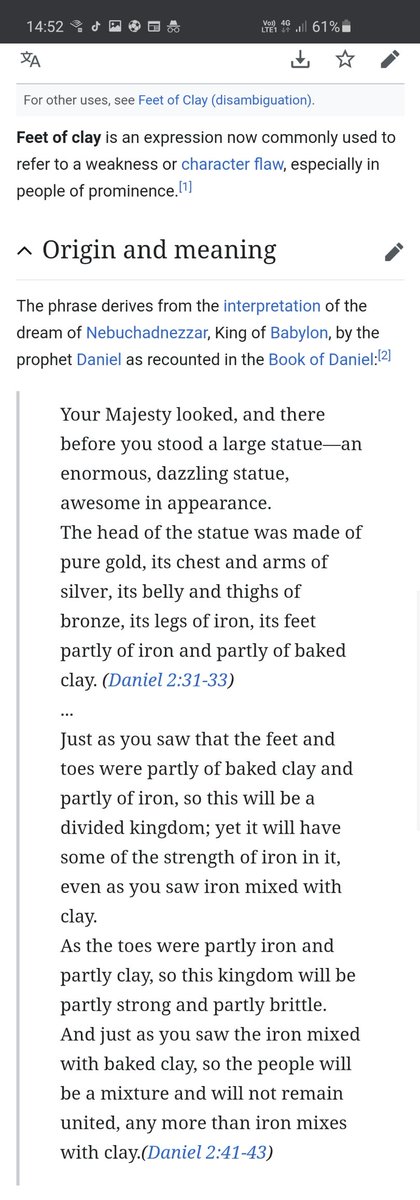

You probably knew this but I realised that "legs of stone" is a play on "feet of clay", an expression deriving from a VERY apt biblical reference.

Seriously, read this:

9/

Seriously, read this:

9/

So LEGS OF STONE = FEET OF CLAY, which invokes a STATUE that despite its grand appearance represents a DIVIDED KINGDOM and FRAGILE RULE.

I *love* a good intertextual ref.

10/

I *love* a good intertextual ref.

10/

More soon!

Line 2 also begins Shelley’s strategy of showing the TRANSIENT NATURE OF POWER by contrasting words relating to power and strength with words relating to ruin and decay.

vast/trunkless is the first such pairing

11/

vast/trunkless is the first such pairing

11/

Alliteration, assonance, internal rhyme and sibilance are also prevalent in the poem and we can see these established in the first couple of line:

trAveller / Antique / lAnd — assonance on ”A”

said / legs

stone / stand

The second line is very sibilant.

12/

trAveller / Antique / lAnd — assonance on ”A”

said / legs

stone / stand

The second line is very sibilant.

12/

It’s easy to spot these things, much harder to pinpoint their “effect”, but for now let’s say they elevate the tone of the poem, adding to the impression of parable or allegory.

More on this later.

13/

13/

3) Stand in the desert...Near them, on the sand

”Sand” symbolises the passing of time (think hourglasses) and is itself a symbol of decay and erosion: it is formed from the slow disintegration of solid stone. Sand is itself a product of time.

14/

”Sand” symbolises the passing of time (think hourglasses) and is itself a symbol of decay and erosion: it is formed from the slow disintegration of solid stone. Sand is itself a product of time.

14/

4) The DESERT is sand on a grand scale, of course, symbolising the loss of Ozymandias’ realm and the way history brought his power to ruin and insignificance.

EGYPTIAN desert in particular is rich with allusive potential, being the stage of the story of Moses in the Bible.

15/

EGYPTIAN desert in particular is rich with allusive potential, being the stage of the story of Moses in the Bible.

15/

Too much to unpick here really, but I think it invokes themes of power, oppression and freedom.

If we think of Jesus’ time in the desert, then it is also a place where hubris and temptation are either succumbed to or resisted. A crucible of character.

16/

If we think of Jesus’ time in the desert, then it is also a place where hubris and temptation are either succumbed to or resisted. A crucible of character.

16/

It’s a subtle thing, but the diction is very carefully controlled here. Between the elevated style of “vast and trunkless” and then “shattered visage”, the phrase “near them on the sand” is almost offhand and casual.

17/

17/

So this is another way of undercutting Ozy’s power: contrasting the description of his statue with a more casual tone that downplays its importance.

18/

18/

MORE CONTEXT:

I now know that Egypt was an important theatre for NAPOLEON, who led an attempted invasion in 1798. And while the invasion was unsuccessful, it was scientifically important. Napoleon took a team of scientists and artists with him, and...

19/

I now know that Egypt was an important theatre for NAPOLEON, who led an attempted invasion in 1798. And while the invasion was unsuccessful, it was scientifically important. Napoleon took a team of scientists and artists with him, and...

19/

Thus was born "Egyptology", and the West's fascination with ancient Egypt.

Napoleon's reign in France ended in 1815, three years before "Ozymandias".

Shelley was a prolific, intellectual and deeply engaged writer and I won't pretend to do justice to him here. But...

20/

Napoleon's reign in France ended in 1815, three years before "Ozymandias".

Shelley was a prolific, intellectual and deeply engaged writer and I won't pretend to do justice to him here. But...

20/

In 1816 , Shelley wrote a sonnet (as Ozymandias is, too) called Feelings Of A Republican On The Fall Of Bonaparte.

It begins with the phrase "I hated thee, fallen tyrant!" and contains imagery which perhaps prefigures that of Ozymandias:

21/

It begins with the phrase "I hated thee, fallen tyrant!" and contains imagery which perhaps prefigures that of Ozymandias:

21/

Thou mightst have built thy throne

Where it had stood even now: thou didst prefer

A frail and bloody pomp which Time has swept

In fragments towards Oblivion.

"Fragments towards Oblivion."

Love it.

22/

Where it had stood even now: thou didst prefer

A frail and bloody pomp which Time has swept

In fragments towards Oblivion.

"Fragments towards Oblivion."

Love it.

22/

Thank you to @TabitaSurge for the steer on Napoleon.

4) Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

A good line for thinking about the poem's use of STRESS and METRE. The poem uses a loose iambic pentameter, with some interesting variations.

The two monosyllabic words HALF SUNK are both stressed to my ears.

23/

A good line for thinking about the poem's use of STRESS and METRE. The poem uses a loose iambic pentameter, with some interesting variations.

The two monosyllabic words HALF SUNK are both stressed to my ears.

23/

They make a little string of monosyllables: "near them, on the sand, half sunk". Again, blunt language undercuts Ozy's grandeur.

The stresses of "half sunk" bring a kind of dead stop in the line: this is the thing to remember. This statue, this great ruler, they're sunk.

24/

The stresses of "half sunk" bring a kind of dead stop in the line: this is the thing to remember. This statue, this great ruler, they're sunk.

24/

Then, although the stressed syllables in SHAttered and VISage are in their correct iambic spot, those two words with stressed at the start sound more sporadic. LIES gives another stress.

The effect?

25/

The effect?

25/

There's a kind of irony to the sound of words here. We can't help but read in a slow, almost grandiose, portentous way -- but what the poem gives this importance and stress to is an image of ruin.

26/

26/

I find the choice of “visage” really interesting. It means the statue’s face, but visage is more than just “face”. It suggests a countenance, a demeanour. It’s a clue that Shelley wants us to think about how the statue conveys Ozymandias himself.

27/

27/

And is there a hint of a double meaning in "lies"?

Lies as in lies on the sand, but lies as in "misrepresents" is interesting to think about.

There are several ambiguous (polysemous) words in the poem and they are crucial to its meaning.

28/

Lies as in lies on the sand, but lies as in "misrepresents" is interesting to think about.

There are several ambiguous (polysemous) words in the poem and they are crucial to its meaning.

28/

4-8) whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

I have thought about these lines a LOT.

29/

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

I have thought about these lines a LOT.

29/

Ozymandias' "frown", "wrinkled lip" and "sneer of cold command" are the hallmarks of a despotic ruler, who looks down on his people and hubristically places himself above them.

30/

30/

"Cold command" especially stands out -- a ruler who is emotionally unattached to his people, devoted only to his own glory.

(AQA Anthology Fans -- "cold clockwork" from BAYONET CHARGE is a nice comparison point here).

31/

(AQA Anthology Fans -- "cold clockwork" from BAYONET CHARGE is a nice comparison point here).

31/

To add to the irony in the poem, however, the shattering of Ozymandias' image by time exposes his attitude in its true malignance -- his hubris and coldness "survive", even when his empire, like the statue, is "lifeless".

32/

32/

EXCEPT.

There's a more complex narrative at work here about the place of the artist in shaping how the ruler is perceived.

A couple of things bug me about the description of Ozy's frown / lip / sneer:

33/

There's a more complex narrative at work here about the place of the artist in shaping how the ruler is perceived.

A couple of things bug me about the description of Ozy's frown / lip / sneer:

33/

First, if you take this as a poem inspired by the statue of Ramesses II, you will notice on THAT statue a distinct lack of frowns, wrinkled lips or sneers:

34/

34/

Because, I would suggest despotic rulers generally DON'T choose to be portrayed as despotic in their official artwork. "Untroubled, regal benevolence" is more the vibe they go for:

35/

35/

Look at what Shelley writes about the sculptor:

"...tell that the sculptor well those passion read"

Praising a sculptor for reading the subject's "passions" is not QUITE the same as saying they captured a likeness.

36/

"...tell that the sculptor well those passion read"

Praising a sculptor for reading the subject's "passions" is not QUITE the same as saying they captured a likeness.

36/

Then there's the very curious line:

"The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed."

This line is syntactically unclear. I take the "hand" as being the sculptor's: he "mocked" Ozy's passions, with the double meaning that...

37/

"The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed."

This line is syntactically unclear. I take the "hand" as being the sculptor's: he "mocked" Ozy's passions, with the double meaning that...

37/

He both copied or imitated them in creating the statue, and that he was perhaps making fun of them.

The "heart" I assume is Ozymandias': his was the heart whose passions fed the hubris and coldness that the statue captures.

38/

The "heart" I assume is Ozymandias': his was the heart whose passions fed the hubris and coldness that the statue captures.

38/

So I think Shelley is interested in showing the different forces that have shaped the statue in the desert:

39/

39/

- Ozymandias' "passions": his heart that feeds his hubris and cruelty, his desire for the statue

- the sculptor's insight by which he "read" Ozymandias

- his hand, the craft he brought to the statue, perhaps crafting an image not entirely what Ozy imagined

40/

- the sculptor's insight by which he "read" Ozymandias

- his hand, the craft he brought to the statue, perhaps crafting an image not entirely what Ozy imagined

40/

- And time, which has swept away his empire and broken his statue, exposing the futility of his power and pride.

41/

41/

9) And on the pedestal these words appear:

I love the use of the word "appear" here. It's a brilliantly active verb -- it suggests the words are emerging, as if we are brushing away the sand to see them.

AND...it's a biblical allusion.

42/

I love the use of the word "appear" here. It's a brilliantly active verb -- it suggests the words are emerging, as if we are brushing away the sand to see them.

AND...it's a biblical allusion.

42/

Remember how "legs of stone" led us via allusion to "feet of clay", belonging to a statue of King Nebuchadnezzar in the Book of Daniel?

"These words appear" leads us back the book of Daniel and to Nebuchadnezzar's son, Belshazzar.

43/

"These words appear" leads us back the book of Daniel and to Nebuchadnezzar's son, Belshazzar.

43/

Belshazzar is holding a feast and drinking wine from silver and golden goblets looted from the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. His wives and concubines drink together.

"As they drank the wine, they praised the gods(H) of gold and silver, of bronze, iron, wood and stone" (DAN 5:4)

44/

"As they drank the wine, they praised the gods(H) of gold and silver, of bronze, iron, wood and stone" (DAN 5:4)

44/

Suddenly the fingers of a human hand appear and begin to write on the wall, in a strange script that no-one can read...until Balshazzar sends for Daniel himself.

And look what it said:

45/

And look what it said:

45/

So "legs of stone" invoked a divided and fragile kingdom; "these words appear" invokes a blaspheming king, unworthy in God's eyes, whose reign is about to end.

And sure enough, Belshazzar was assassinated that very night.

46/

And sure enough, Belshazzar was assassinated that very night.

46/

10) "My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings"

"King of Kings" is an interesting one: to a Christian it would definitely refer to God or to Jesus, although Wikipedia tells me that historical rulers have used the title too. It stands for Ozymandias' hubris here.

47/

"King of Kings" is an interesting one: to a Christian it would definitely refer to God or to Jesus, although Wikipedia tells me that historical rulers have used the title too. It stands for Ozymandias' hubris here.

47/

Imagining yourself as a god, or equal to the gods, is of course the classic hubristic act, invariably punished by the gods themselves or by your fellow man. Ozymandias' hubris was misplaced -- time has reduced his empire to sand.

48/

48/

11) "Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Shelley gives an ironic weight to these words by disrupting the iambic pentameter that more or less makes the rest of the poem: LOOK on my WORKS ye MIGHTy and desPAIR.

49/

Shelley gives an ironic weight to these words by disrupting the iambic pentameter that more or less makes the rest of the poem: LOOK on my WORKS ye MIGHTy and desPAIR.

49/

Ozymandias' words don't mean what he wanted them to mean:

He wanted the "Mighty" to "despair" because of his awesome, godlike power.

But now, those "mighty" onlookers would despair because all power is transient and destined for oblivion.

50/

He wanted the "Mighty" to "despair" because of his awesome, godlike power.

But now, those "mighty" onlookers would despair because all power is transient and destined for oblivion.

50/

12-14) Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

I hear a double meaning in "nothing beside remains":

51/

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

I hear a double meaning in "nothing beside remains":

51/

- Nothing remains in the desert beside (alongside) the statue

- The statue itself is nothing beside(s) remains

52/

- The statue itself is nothing beside(s) remains

52/

"Colossal wreck" and "boundless and bare" go with "vast and trunkless" and "cold command" in the poem's use of ANTITHESIS:

words suggesting power and strength contrasted with words suggesting ruin and emptiness.

The antithesis emphasises the contrast of Ozy then and now.

53/

words suggesting power and strength contrasted with words suggesting ruin and emptiness.

The antithesis emphasises the contrast of Ozy then and now.

53/

I wonder if Shelley was thinking of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar --

CASSIUS:

Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves.

54/

CASSIUS:

Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves.

54/

(PS. this might be nothing but...

In these antithetical pairs:

cold command

colossal wreck

boundless and bare

a word of classical origin (command, colossal, boundless) is contrasted with a word of Anglo-Saxon/Germanic origin (cold, wreck, bare).

55/

In these antithetical pairs:

cold command

colossal wreck

boundless and bare

a word of classical origin (command, colossal, boundless) is contrasted with a word of Anglo-Saxon/Germanic origin (cold, wreck, bare).

55/

I think the contrast aids the jarring sense of antithesis, and gives a pleasing sense of clashing histories...)

56/

56/

It only remains to comment on how masterfully Shelley uses ALLITERATION, RHYME and ASSONANCE in these final lines:

- RemaINs, decAY, BAre, awAY

- rOUnd, BOUNDless

- wrEck, lEvel, strEtch

It creates a stately, poised tone at the end, funereal, elegiac.

57/

- RemaINs, decAY, BAre, awAY

- rOUnd, BOUNDless

- wrEck, lEvel, strEtch

It creates a stately, poised tone at the end, funereal, elegiac.

57/

And that series of alliterative pairs: boundless and bare, lone and level, sands stretch...

They add to the sense of desolation, like the slow ringing of a bell.

58/

They add to the sense of desolation, like the slow ringing of a bell.

58/

And isn't "far away" the perfect ending, emphasising the vast emptiness of Ozymandias' former Kingdom, and his distance from our own perspective.

59/

59/

So to conclude:

Ozymandias is a poem about power. It's a great poem to use for comparison because it gives a widely applicable argument about the nature of power itself: the even the greatest, most absolute power is transient, that all rulers fall, that hubris is punished.

60/

Ozymandias is a poem about power. It's a great poem to use for comparison because it gives a widely applicable argument about the nature of power itself: the even the greatest, most absolute power is transient, that all rulers fall, that hubris is punished.

60/

But it's just as much a poem about how we tell stories about power, how history is shaped: all those multiple meanings, the ambiguous figure of the sculptor, the Biblical allusions.

61/

61/

Not even the most powerful can control how their story is told in the future. Time and the artist will have their say.

62/

62/

This was 62 tweets about the poem Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Thanks for reading!

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh