1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand inventory turnover.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand inventory turnover.

2/

Imagine that you own 2 stores: G and J.

G is a grocery store. It has low gross margins (30%). You buy cabbages for 70 cents and sell them for a dollar.

J is a jewelry store. It has much higher gross margins (60%). You buy diamonds for $40K and sell them for $100K.

Imagine that you own 2 stores: G and J.

G is a grocery store. It has low gross margins (30%). You buy cabbages for 70 cents and sell them for a dollar.

J is a jewelry store. It has much higher gross margins (60%). You buy diamonds for $40K and sell them for $100K.

3/

Which store is likely to give you better returns over time?

As investors, we usually associate higher gross margins with better returns.

So, you may be tempted to say that J will give you better returns than G.

But in fact, just the opposite may turn out to be true.

Which store is likely to give you better returns over time?

As investors, we usually associate higher gross margins with better returns.

So, you may be tempted to say that J will give you better returns than G.

But in fact, just the opposite may turn out to be true.

4/

Why?

Because, although gross margins are important, they're not the only factor determining your returns.

To really understand a retail business (like a grocery or jewelry store), you need to study the movement of inventory in and out of the business.

Why?

Because, although gross margins are important, they're not the only factor determining your returns.

To really understand a retail business (like a grocery or jewelry store), you need to study the movement of inventory in and out of the business.

5/

What exactly is "inventory"?

It's a fancy accounting term.

It just means "stuff that has been bought but not yet sold".

What exactly is "inventory"?

It's a fancy accounting term.

It just means "stuff that has been bought but not yet sold".

6/

For example, suppose G (your grocery store) buys a cabbage from a farmer.

This cabbage sits on a shelf -- until someone buys it.

For as long as the cabbage is on the shelf (ie, the cabbage has been bought by G, but not yet sold), it counts as "inventory".

For example, suppose G (your grocery store) buys a cabbage from a farmer.

This cabbage sits on a shelf -- until someone buys it.

For as long as the cabbage is on the shelf (ie, the cabbage has been bought by G, but not yet sold), it counts as "inventory".

7/

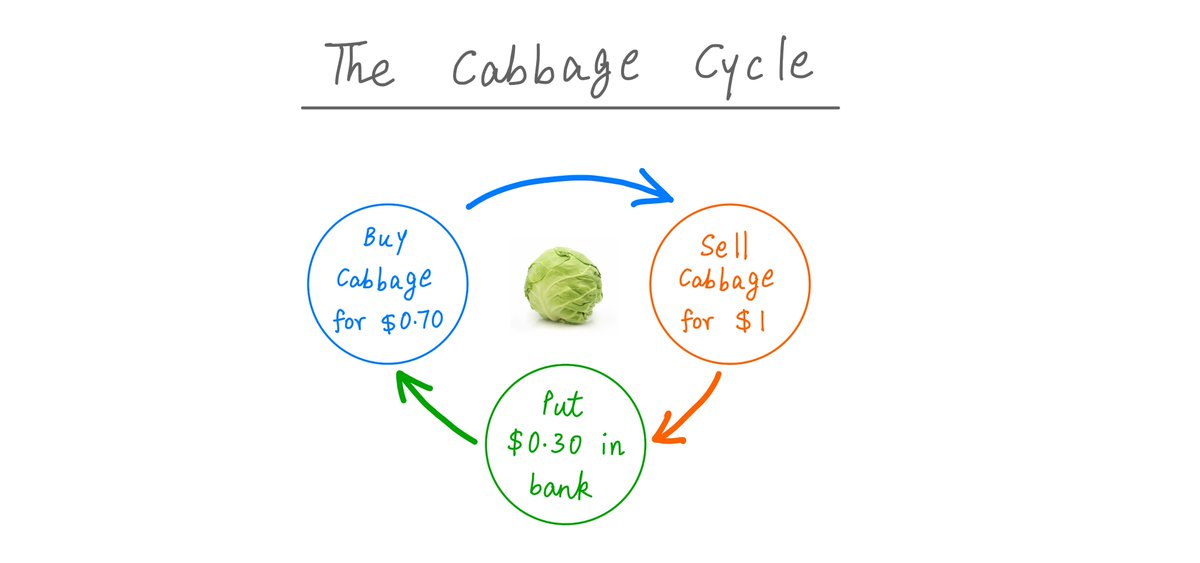

Suppose G pays the farmer $0.70 when it buys the cabbage from him.

Immediately after buying the cabbage, G is $0.70 "out of pocket". But it has $0.70 worth of inventory (the cabbage).

Eventually, G sells the cabbage for $1. That's how G gets its 30% gross margin.

Suppose G pays the farmer $0.70 when it buys the cabbage from him.

Immediately after buying the cabbage, G is $0.70 "out of pocket". But it has $0.70 worth of inventory (the cabbage).

Eventually, G sells the cabbage for $1. That's how G gets its 30% gross margin.

8/

The key question is: how much time does it take for G to sell the cabbage?

The sooner G sells the cabbage, the sooner it gets its money back. Then it can use this money to buy another cabbage.

And the "cabbage cycle" can continue:

The key question is: how much time does it take for G to sell the cabbage?

The sooner G sells the cabbage, the sooner it gets its money back. Then it can use this money to buy another cabbage.

And the "cabbage cycle" can continue:

9/

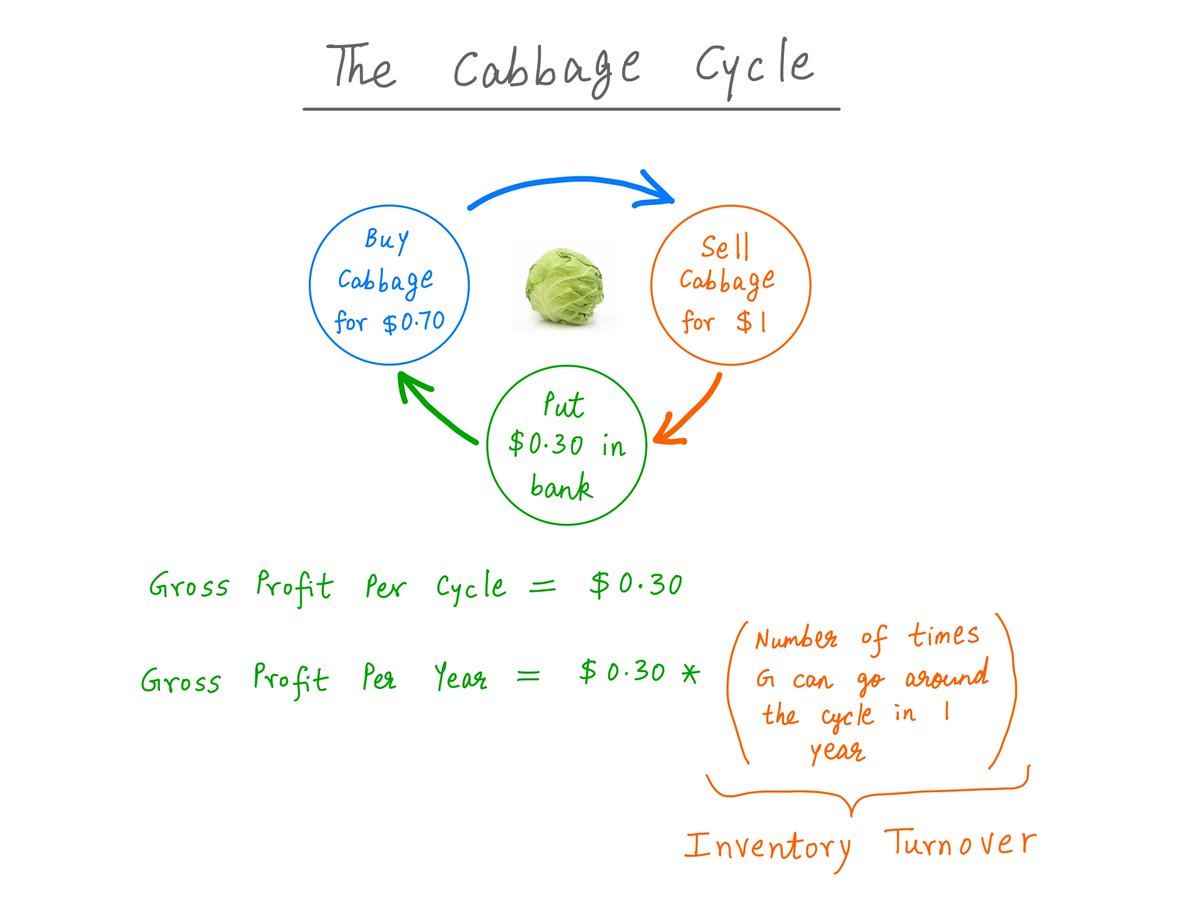

See how G pockets $0.30 in gross profits every time it goes around the cabbage cycle?

For example, suppose G is able to sell cabbages the same day it buys them.

Then, G can execute the cabbage cycle 365 times in a year. This is $0.30*365 = $109.50 in annual gross profits.

See how G pockets $0.30 in gross profits every time it goes around the cabbage cycle?

For example, suppose G is able to sell cabbages the same day it buys them.

Then, G can execute the cabbage cycle 365 times in a year. This is $0.30*365 = $109.50 in annual gross profits.

10/

But suppose the cabbages sit on G's shelves for about a week before someone buys them.

Then, G can execute the cabbage cycle only about 52 times per year. This is only $0.30*52 = $15.60 in annual gross profits.

But suppose the cabbages sit on G's shelves for about a week before someone buys them.

Then, G can execute the cabbage cycle only about 52 times per year. This is only $0.30*52 = $15.60 in annual gross profits.

11/

Thus, the "number of times G can execute the cabbage cycle in a year" is super important.

In fancy business speak, this number is called "inventory turnover".

Higher the inventory turnover, higher the gross profits.

Thus, the "number of times G can execute the cabbage cycle in a year" is super important.

In fancy business speak, this number is called "inventory turnover".

Higher the inventory turnover, higher the gross profits.

12/

If G sells cabbages the same day it buys them, inventory turnover will be 365.

But if G takes a week to sell the cabbages, inventory turnover will drop to 52 -- taking gross profits down with it.

If G sells cabbages the same day it buys them, inventory turnover will be 365.

But if G takes a week to sell the cabbages, inventory turnover will drop to 52 -- taking gross profits down with it.

13/

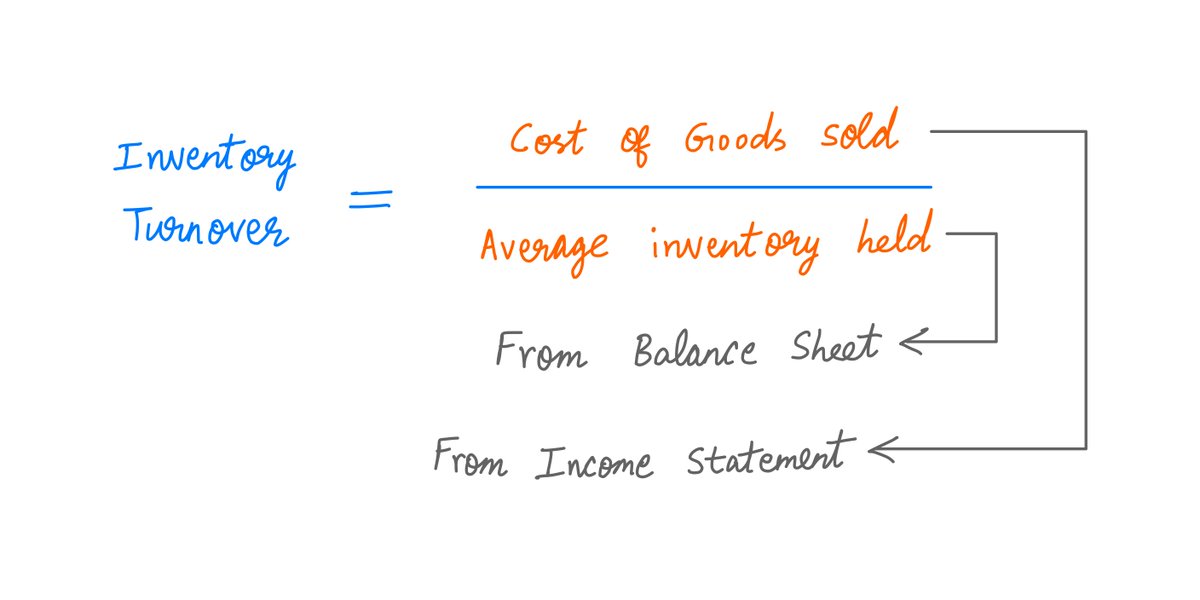

Here's a formula you can use to estimate inventory turnover: just divide cost of goods sold (COGS) by the average inventory held during the year.

Here's a formula you can use to estimate inventory turnover: just divide cost of goods sold (COGS) by the average inventory held during the year.

14/

Note: many investors estimate inventory turnover by dividing *revenue* -- instead of *COGS* -- by inventory.

But this is not strictly correct: inventory is held on the books at *cost price*, whereas revenue is booked at *sale price*.

(h/t Geoff Gannon @FocusedCompound).

Note: many investors estimate inventory turnover by dividing *revenue* -- instead of *COGS* -- by inventory.

But this is not strictly correct: inventory is held on the books at *cost price*, whereas revenue is booked at *sale price*.

(h/t Geoff Gannon @FocusedCompound).

15/

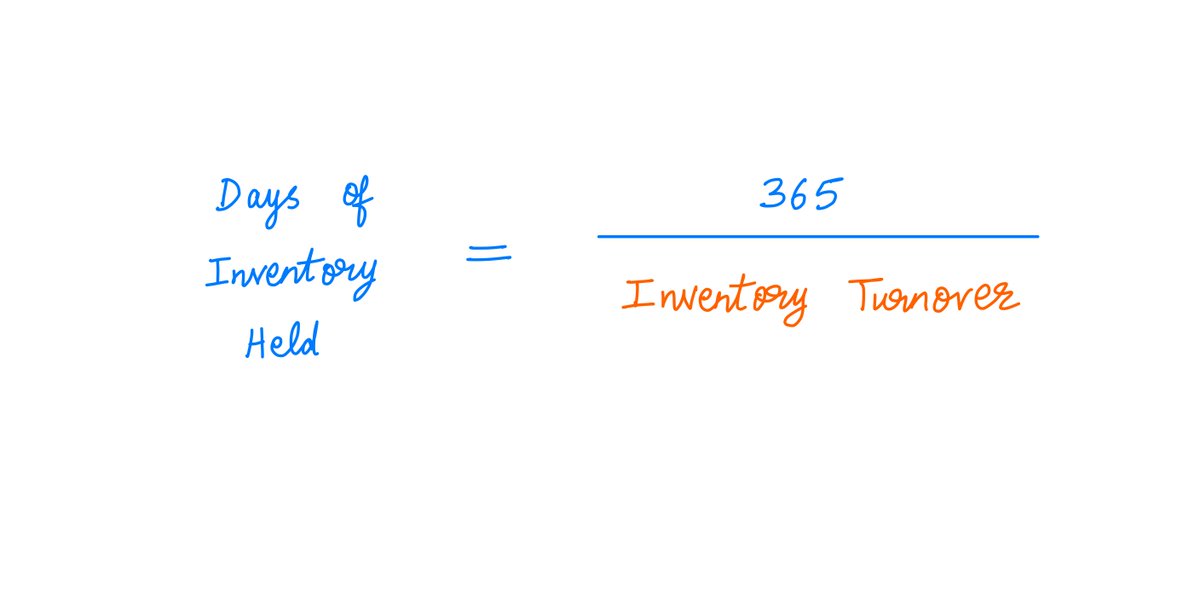

A closely related metric is "days of inventory held" -- the inverse of inventory turnover.

This is how many days a business will take to sell all the inventory it holds:

A closely related metric is "days of inventory held" -- the inverse of inventory turnover.

This is how many days a business will take to sell all the inventory it holds:

16/

These concepts can help us compare our grocery store business (G) with our jewelry store business (J).

The fact is: turning around cabbages is much easier than turning around diamonds.

So inventory turnover will be higher at G, but gross margins will be higher at J.

These concepts can help us compare our grocery store business (G) with our jewelry store business (J).

The fact is: turning around cabbages is much easier than turning around diamonds.

So inventory turnover will be higher at G, but gross margins will be higher at J.

17/

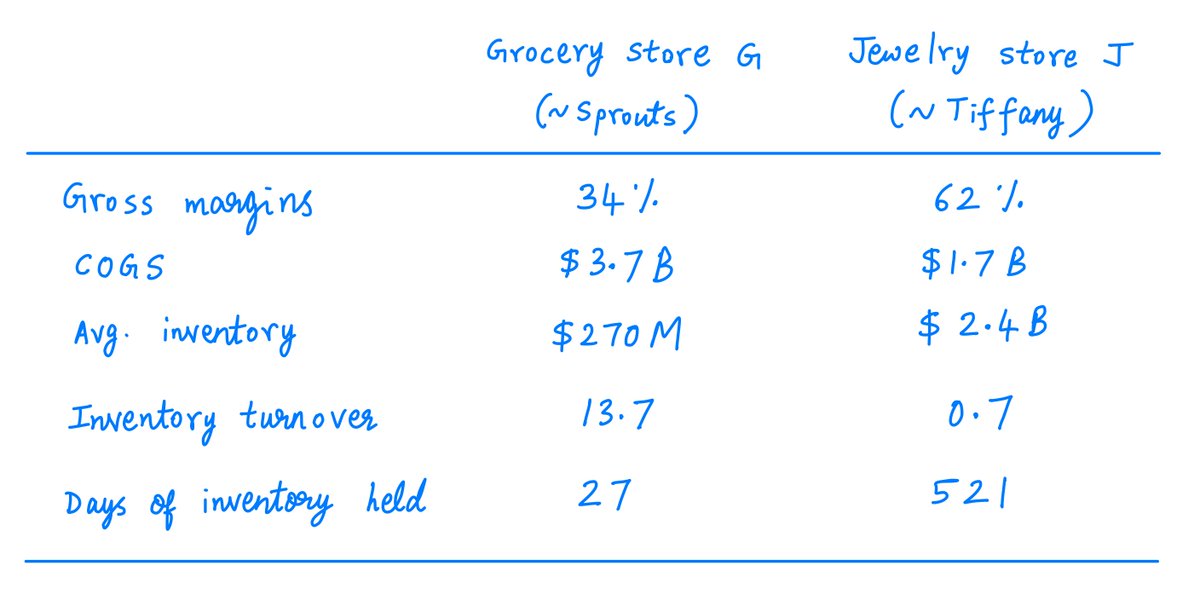

For example, suppose G is comparable to a Sprouts store, and J is comparable to a Tiffany store.

Then, here's how G will stack up against J (based on the 2019 financials of Sprouts and Tiffany):

For example, suppose G is comparable to a Sprouts store, and J is comparable to a Tiffany store.

Then, here's how G will stack up against J (based on the 2019 financials of Sprouts and Tiffany):

18/

Key lesson: Gross margins alone don't tell you how much a business will return on capital employed. You should also consider inventory turnover.

Key lesson: Gross margins alone don't tell you how much a business will return on capital employed. You should also consider inventory turnover.

19/

For example, if your capital is tied up in inventory that takes a long time to sell (like 521 days in the case of Tiffany), you may not earn a high return on that capital -- even if you eventually sell the inventory at a big markup.

For example, if your capital is tied up in inventory that takes a long time to sell (like 521 days in the case of Tiffany), you may not earn a high return on that capital -- even if you eventually sell the inventory at a big markup.

20/

But if you can turn around your inventory quickly (like in 27 days, as in Sprouts), you may be able to earn a high return on your capital even if your gross margins aren't that big.

But if you can turn around your inventory quickly (like in 27 days, as in Sprouts), you may be able to earn a high return on your capital even if your gross margins aren't that big.

21/

OK. So both gross margins and inventory turnover matter.

What else matters?

Well, the timing of cash flows is a key factor. This includes 2 components:

1. How much time customers take to pay you for goods, and

2. How much time you can take to pay suppliers for inventory.

OK. So both gross margins and inventory turnover matter.

What else matters?

Well, the timing of cash flows is a key factor. This includes 2 components:

1. How much time customers take to pay you for goods, and

2. How much time you can take to pay suppliers for inventory.

22/

How much time customers take to pay.

In the best businesses, customers pay *upfront* for goods they buy later.

But not all businesses are this fortunate.

Generally, the more time customers take to pay for goods, the more capital is tied up in receivables earning 0%.

How much time customers take to pay.

In the best businesses, customers pay *upfront* for goods they buy later.

But not all businesses are this fortunate.

Generally, the more time customers take to pay for goods, the more capital is tied up in receivables earning 0%.

23/

For example, Starbucks is wonderful in this respect.

When you load your Starbucks card with money, you're pre-paying Starbucks for coffee that you will buy later.

Here's an excellent article about this (h/t @jp_koning, @rationalwalk): jpkoning.blogspot.com/2019/08/starbu…

For example, Starbucks is wonderful in this respect.

When you load your Starbucks card with money, you're pre-paying Starbucks for coffee that you will buy later.

Here's an excellent article about this (h/t @jp_koning, @rationalwalk): jpkoning.blogspot.com/2019/08/starbu…

24/

How much time you can take to pay suppliers for the inventory you buy from them.

Generally, the longer you can take, the better your return on capital.

In effect, your suppliers are paying for part of your inventory. It's their capital tied up on your shelves, not yours.

How much time you can take to pay suppliers for the inventory you buy from them.

Generally, the longer you can take, the better your return on capital.

In effect, your suppliers are paying for part of your inventory. It's their capital tied up on your shelves, not yours.

25/

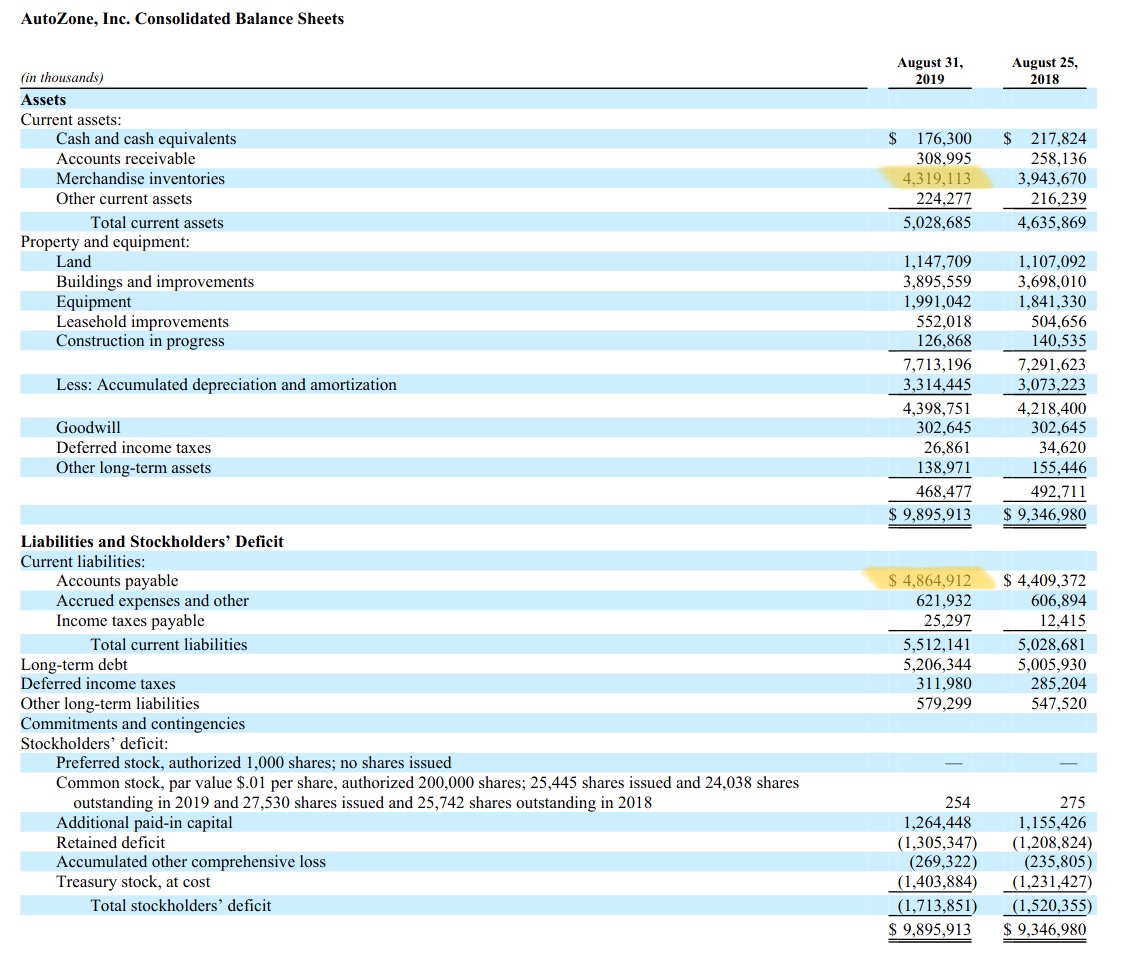

AutoZone is great in this regard.

As of Aug 31 2019, they had $4.3B in inventory, but they owed $4.9B to their suppliers.

This means they don't pay for inventory until *after* they sell it -- at a 50%+ gross profit!

This is called "negative working capital". It's rare.

AutoZone is great in this regard.

As of Aug 31 2019, they had $4.3B in inventory, but they owed $4.9B to their suppliers.

This means they don't pay for inventory until *after* they sell it -- at a 50%+ gross profit!

This is called "negative working capital". It's rare.

26/

Thus, there are 4 inventory turnaround parameters: 1) when you buy inventory, 2) when you pay suppliers for it, 3) when you sell it, and 4) when you get paid by customers for it.

These parameters, in addition to gross margins, determine the business's returns on capital.

Thus, there are 4 inventory turnaround parameters: 1) when you buy inventory, 2) when you pay suppliers for it, 3) when you sell it, and 4) when you get paid by customers for it.

These parameters, in addition to gross margins, determine the business's returns on capital.

27/

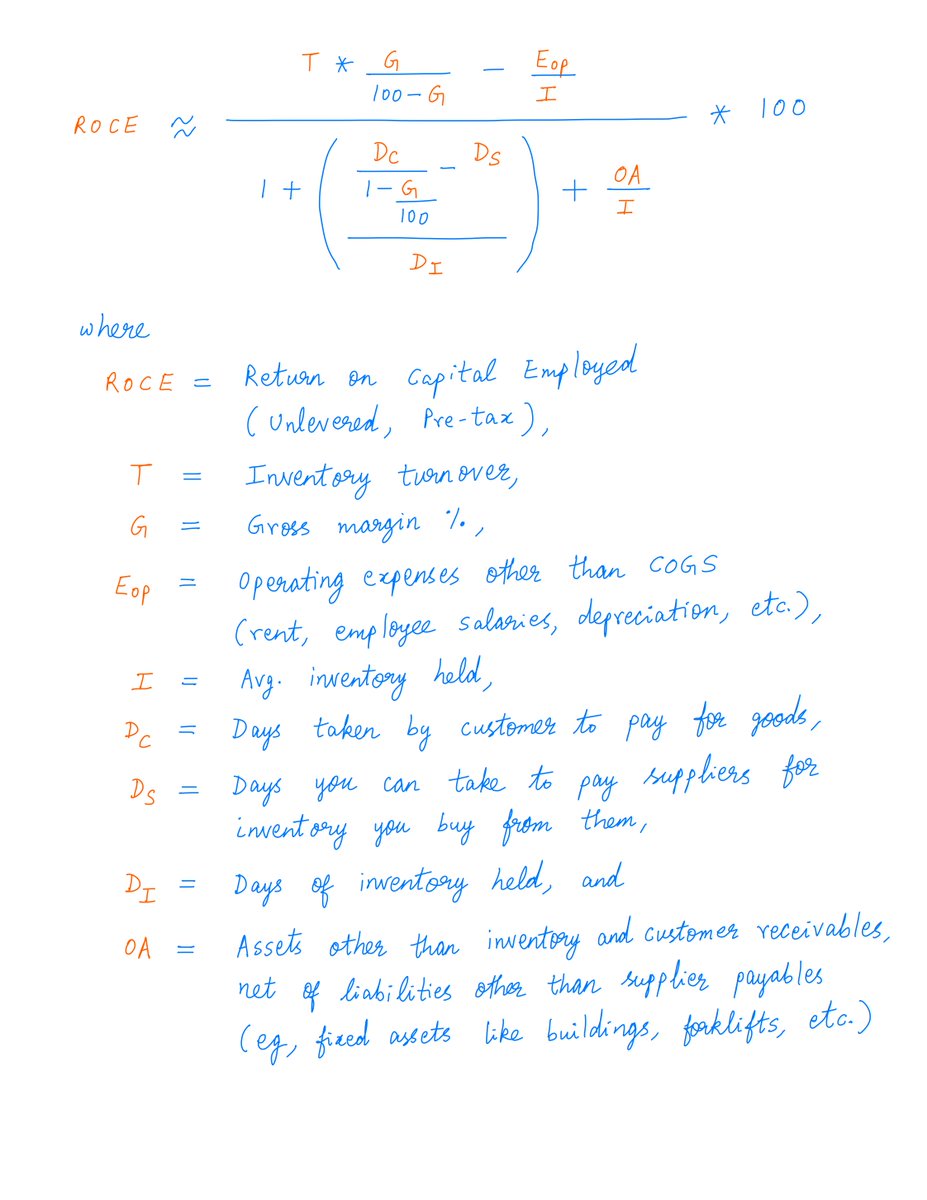

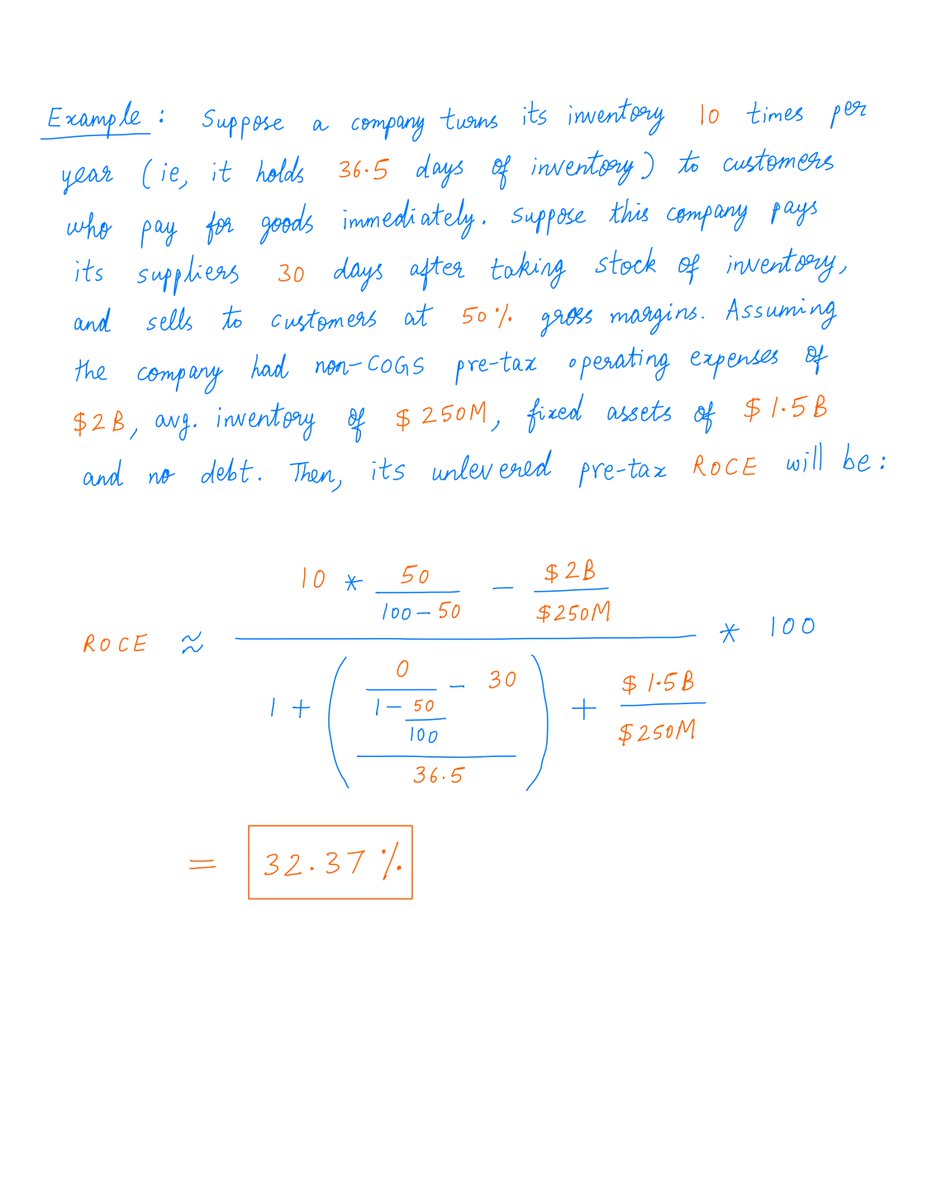

Here's a formula that ties all these parameters together, to predict the unlevered, pre-tax ROCE (Return on Capital Employed) that the business will earn -- along with an example showing how to apply the formula:

Here's a formula that ties all these parameters together, to predict the unlevered, pre-tax ROCE (Return on Capital Employed) that the business will earn -- along with an example showing how to apply the formula:

28/

The formula above shows that ROCE will depend on both gross margins *and* inventory turnover parameters.

Also, the formula shows that ROCE will depend on operating efficiencies: you want to keep non-COGS costs like rent and employee salaries under control.

The formula above shows that ROCE will depend on both gross margins *and* inventory turnover parameters.

Also, the formula shows that ROCE will depend on operating efficiencies: you want to keep non-COGS costs like rent and employee salaries under control.

29/

And also, the formula takes into account the fixed assets (like buildings) required to earn this ROCE. In general, businesses that need more in the way of fixed assets tend to have lower ROCEs.

And also, the formula takes into account the fixed assets (like buildings) required to earn this ROCE. In general, businesses that need more in the way of fixed assets tend to have lower ROCEs.

30/

I want to stress that this formula is approximate.

And it's only valid when there's no debt -- the "unlevered" stipulation.

Retail is complicated. Growth rates, seasonality, capex, debt structure -- all come into play.

No formula is perfect. But some formulas are useful.

I want to stress that this formula is approximate.

And it's only valid when there's no debt -- the "unlevered" stipulation.

Retail is complicated. Growth rates, seasonality, capex, debt structure -- all come into play.

No formula is perfect. But some formulas are useful.

31/

If there's one thing to take away from this thread, it's the importance of thinking in multiple dimensions.

Don't look at gross margins alone, or inventory turnover alone. Look at the combined effect of all the key factors.

Thanks for reading! Enjoy your weekend!

/End

If there's one thing to take away from this thread, it's the importance of thinking in multiple dimensions.

Don't look at gross margins alone, or inventory turnover alone. Look at the combined effect of all the key factors.

Thanks for reading! Enjoy your weekend!

/End

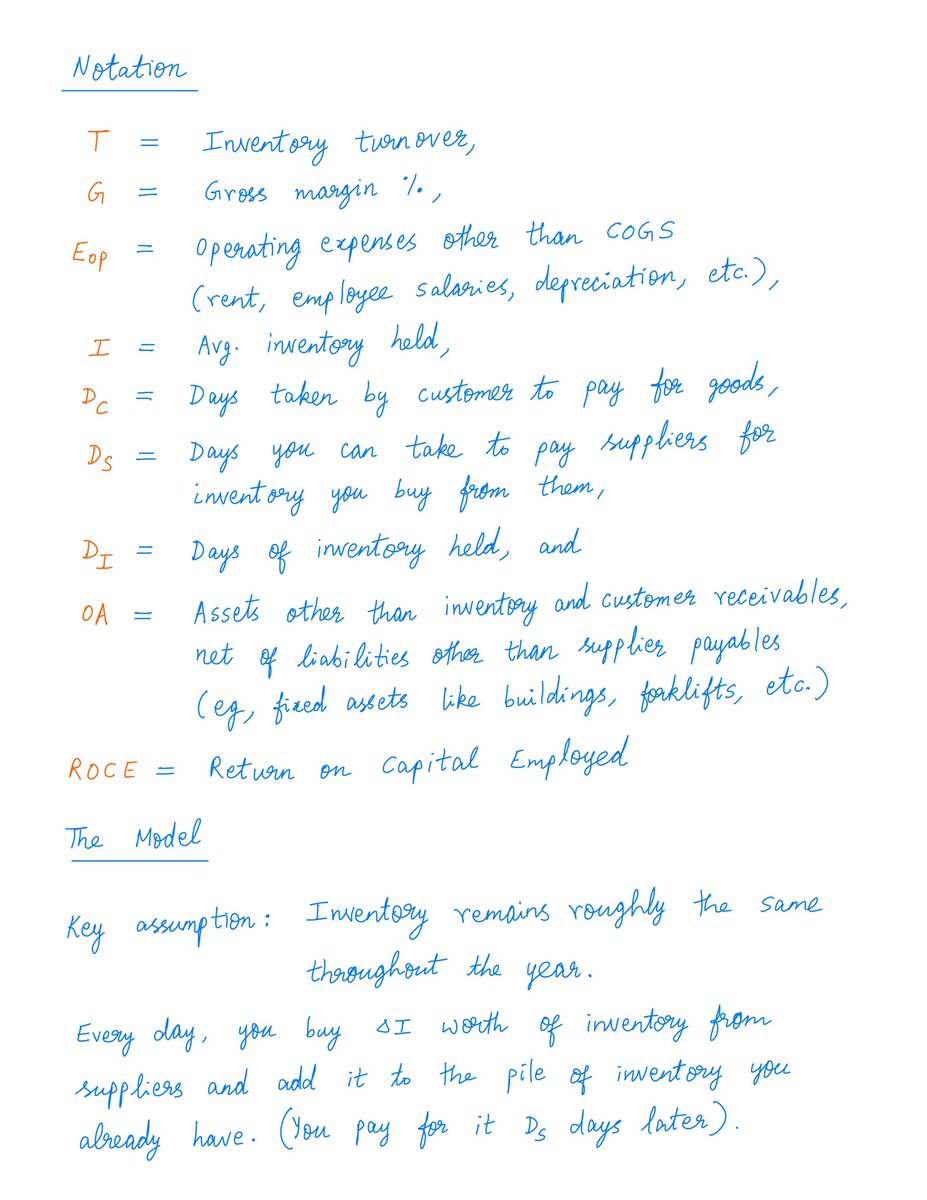

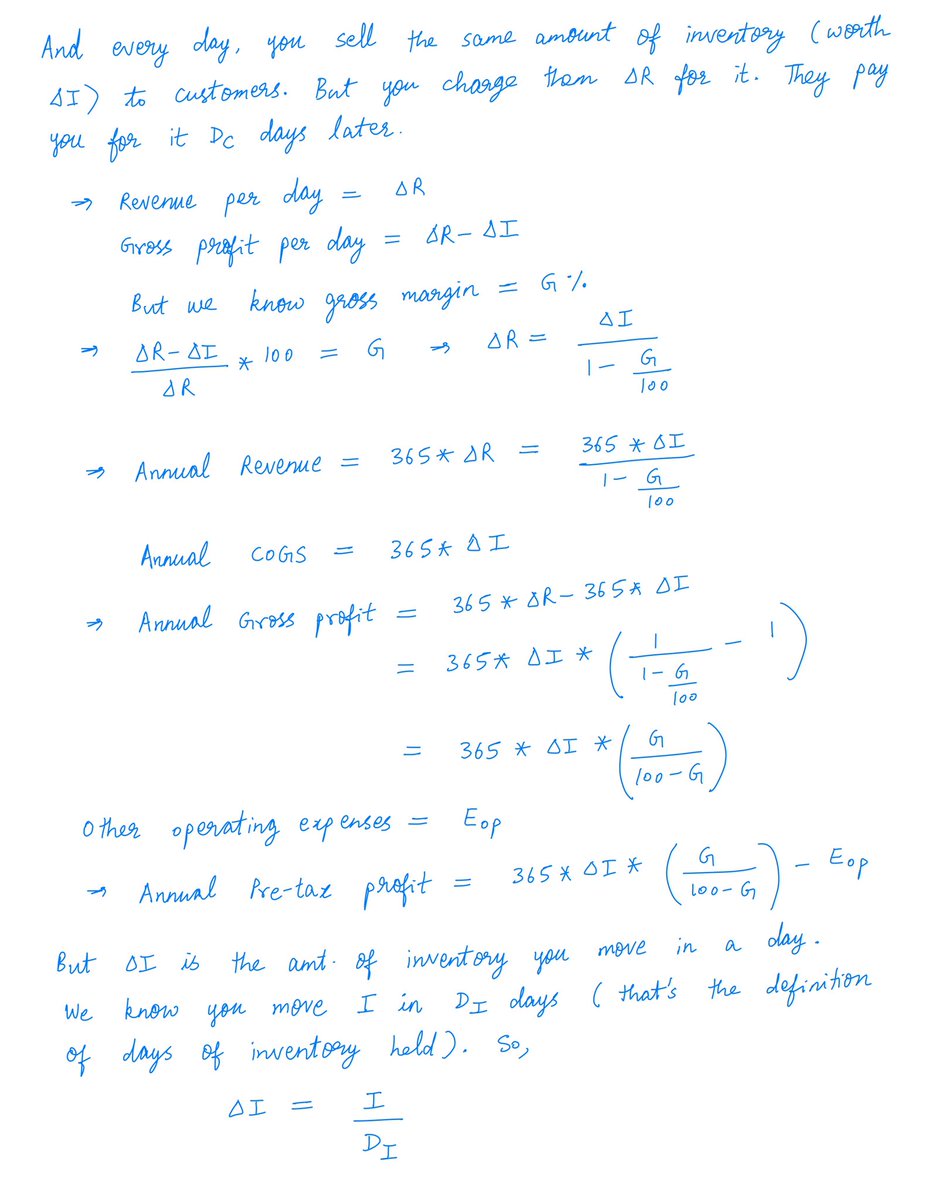

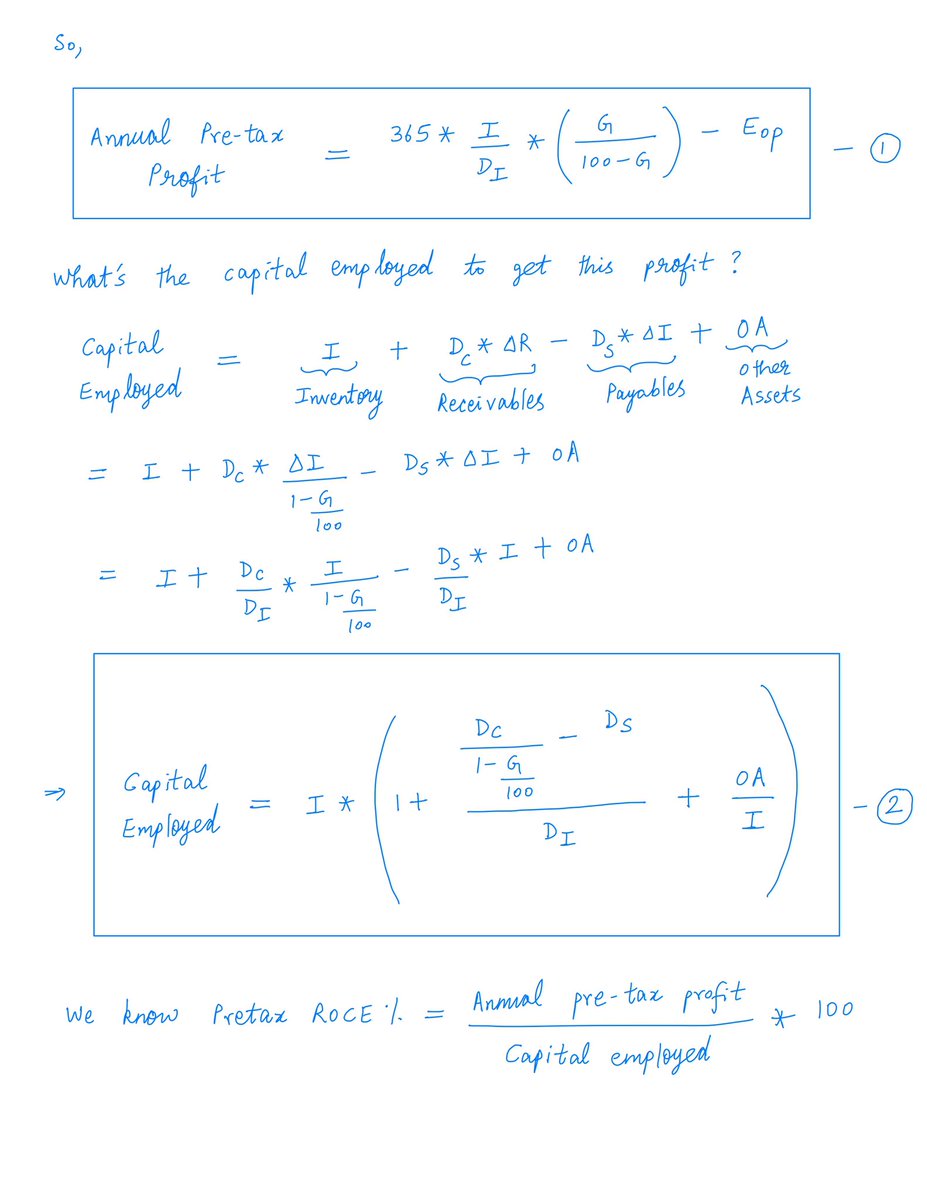

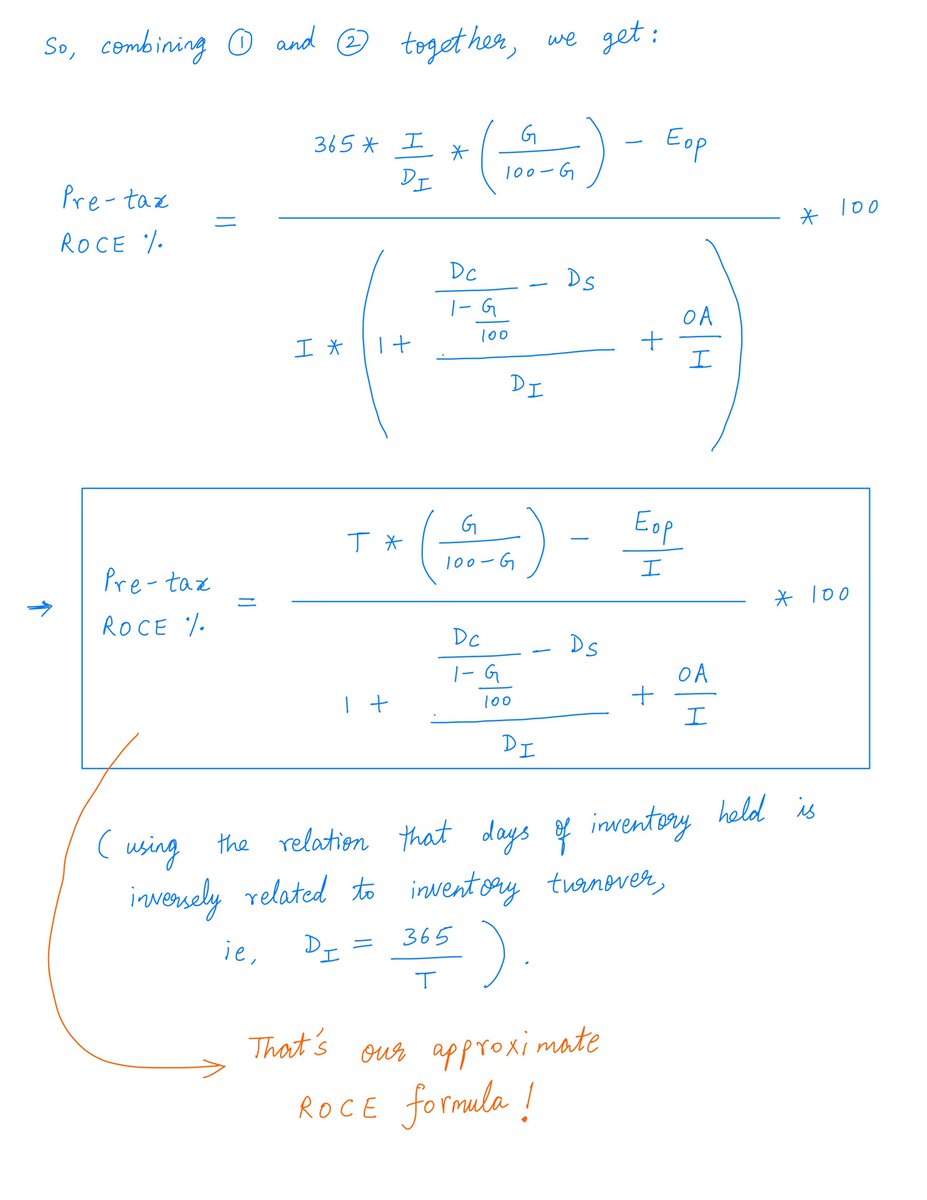

Some folks wanted to know how I got the ROCE formula in Tweet 27 above.

Hence this “appendix tweet” with my derivation. See pics.

(Don’t worry if you don’t understand the math. Just remember that both gross margins *and* inventory turnover matter — not just one or the other.)

Hence this “appendix tweet” with my derivation. See pics.

(Don’t worry if you don’t understand the math. Just remember that both gross margins *and* inventory turnover matter — not just one or the other.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh