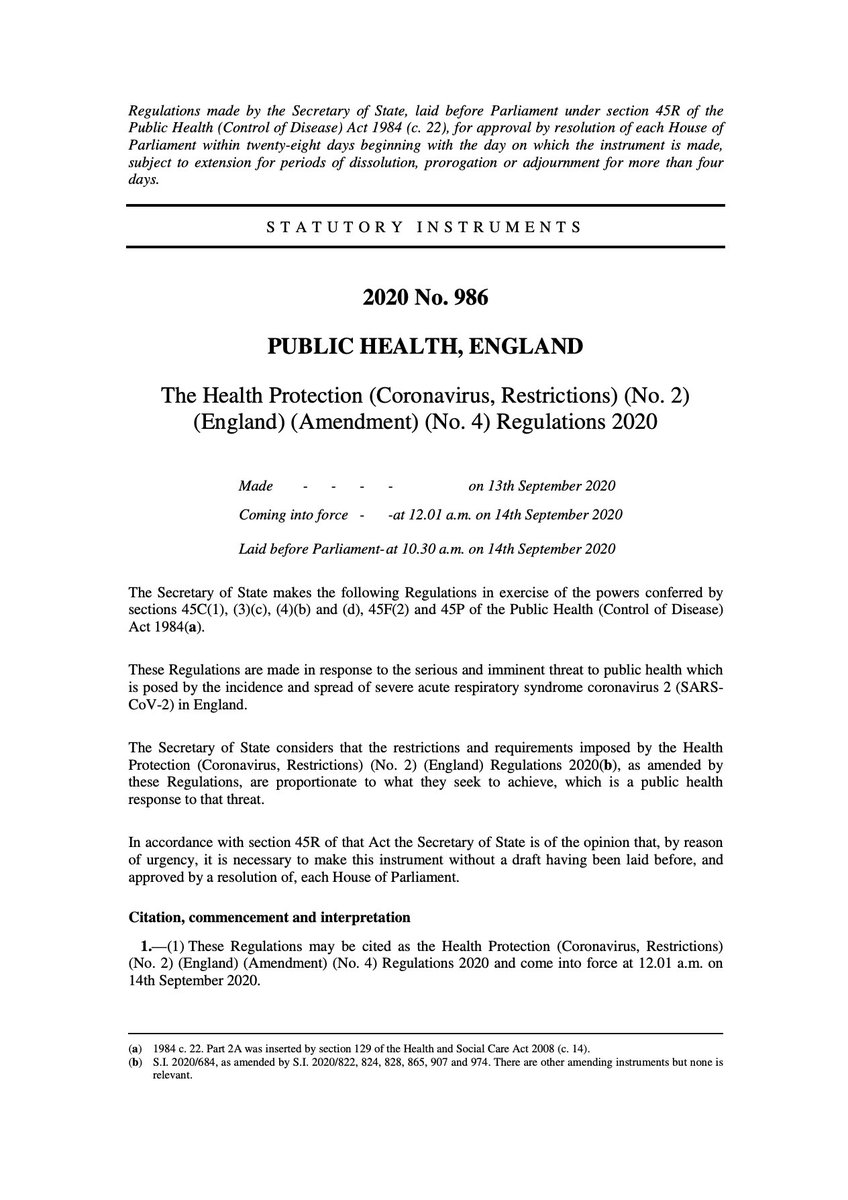

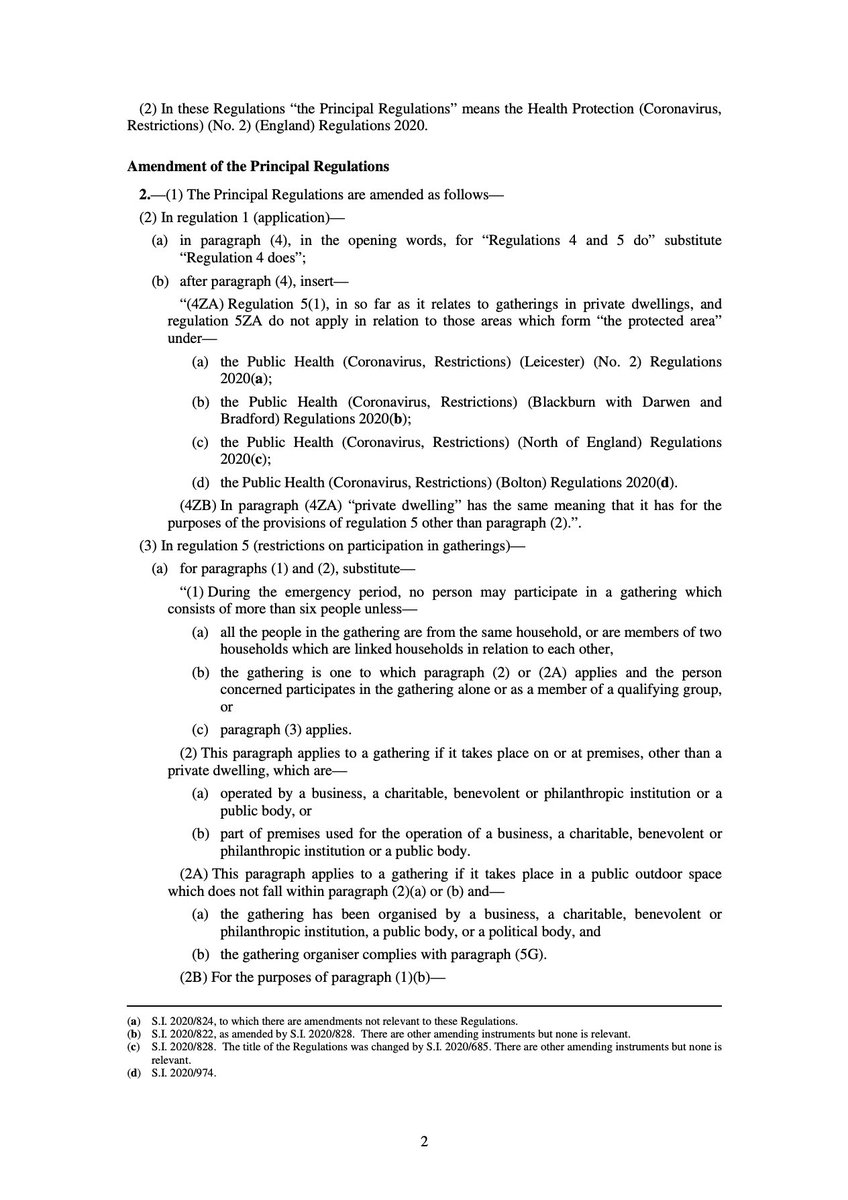

The new coronavirus regulations for England were published a few minutes before they entered into force and without any parliamentary scrutiny. @MattHancock said they were ‘super-simple’. They’re not — and they raise significant constitutional issues. /1

legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2020/986/…

legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2020/986/…

First, publishing complex new regulations literally minutes before they become law compromises the rule of law: frequent/sudden changes diminish legal certainty, making it hard for law-abiding individuals and businesses to plan accordingly. /2

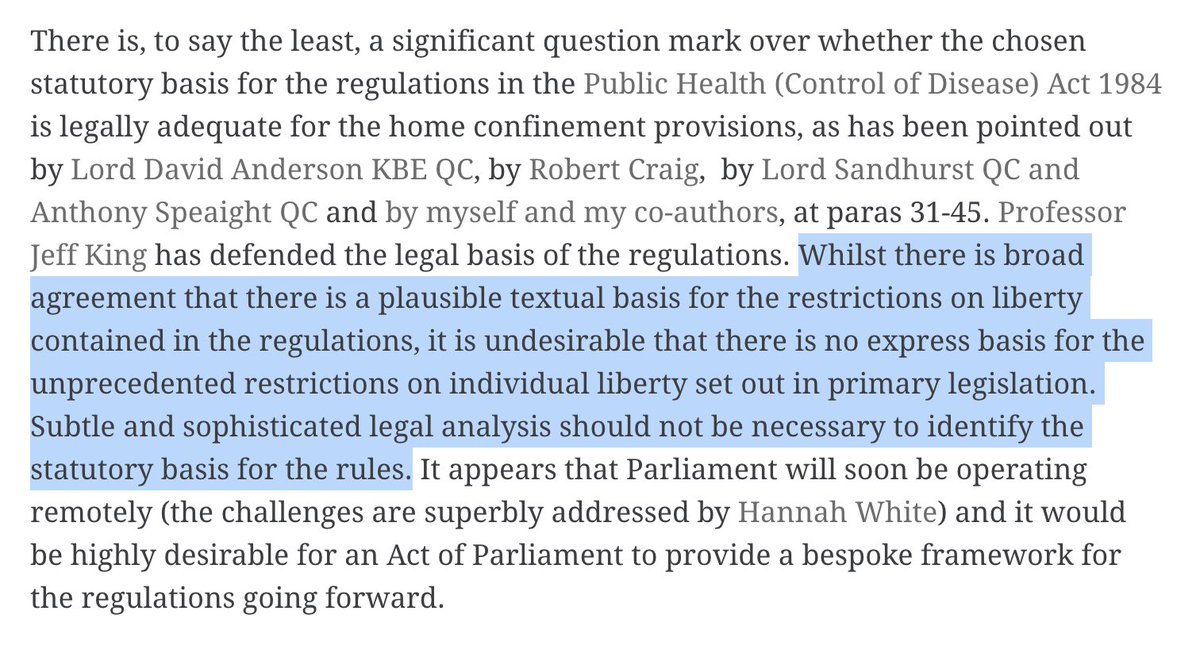

Second, the Government continues to rely on the Public Health Act 1984 to make these regulations. As @TomRHickman has argued, a clearer statutory basis for significant restrictions on liberty would, at the very least, be constitutionally desirable. /3 ukconstitutionallaw.org/2020/04/16/tom…

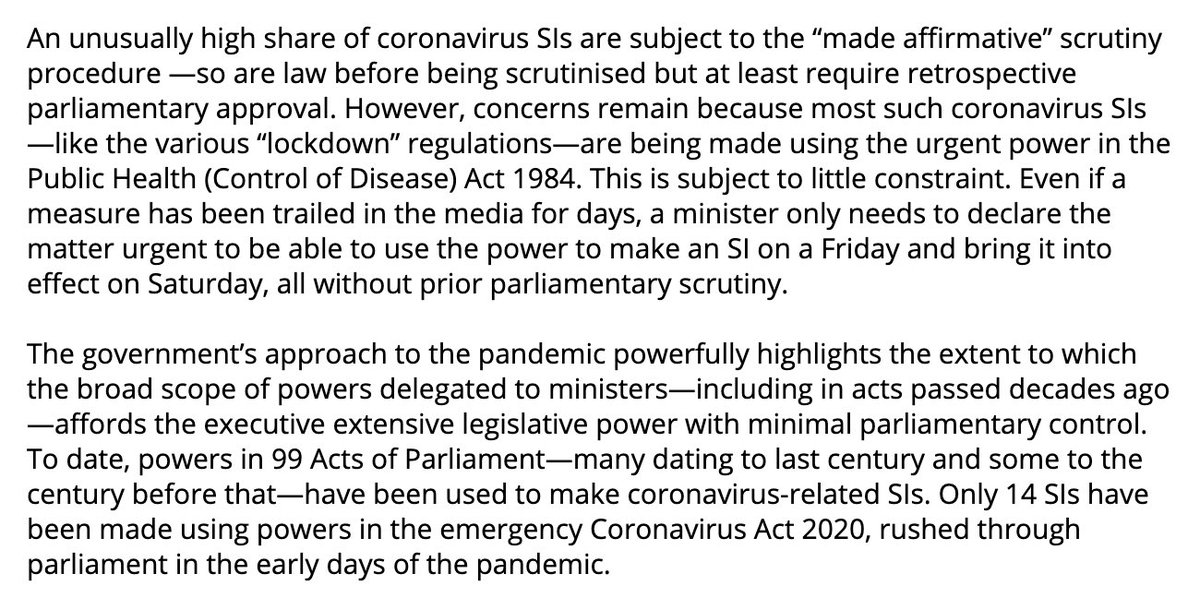

Third, not only are the new regulations highly technical: they also involve substantive policy choices that have significant implications for individuals. This casts doubt on the appropriateness of using the ‘made affirmative’ procedure. /4 statutoryinstruments.parliament.uk/procedure/iWug…

As @RuthFox01 and @Brigid_Fowler of the @HansardSociety have argued, the extensive use of this procedure for coronavirus-related legislation raises serious concerns, given the ‘inadequate scrutiny process’ inherent in this approach. /5 prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/brexi…

The approach in this area is part of a broader constitutional malaise, whereby Parliament is bypassed and judicial oversight resisted by an Executive that increasingly appears to regard constitutional checks and balances as an unwelcome irritant. /6 publiclawforeveryone.com/2020/09/13/the…

Finally, for those grappling with the new regulations, here is an excellent thread by @AdamWagner1 taking a first look at them. /ends

https://twitter.com/adamwagner1/status/1305276954816503808?s=21

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh