1/11

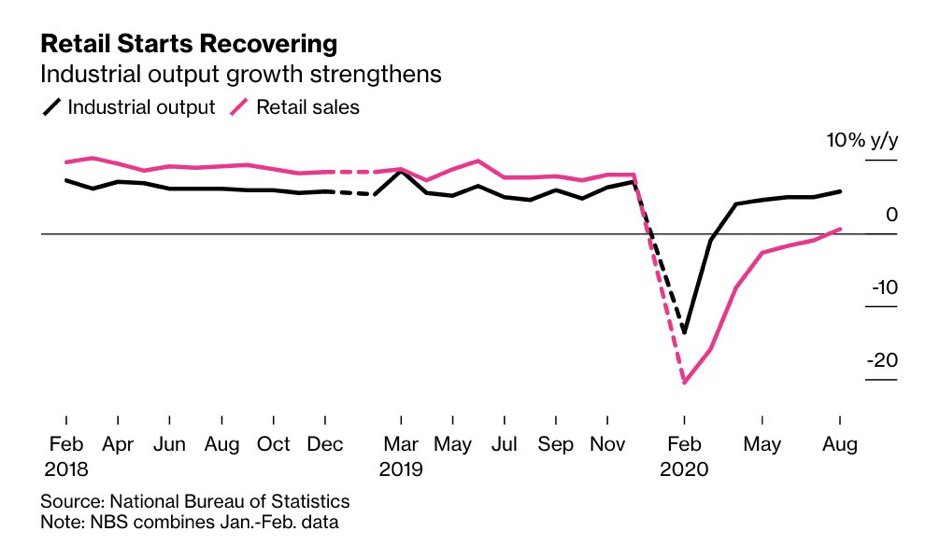

While many analysts see the most recent NBS data release – with retail sales showing the first monthly year-on-year increase in 2020 and industrial production up 5.6% year on year in August – as evidence of a “solid” economic recovery in China, this graph shows just how...

While many analysts see the most recent NBS data release – with retail sales showing the first monthly year-on-year increase in 2020 and industrial production up 5.6% year on year in August – as evidence of a “solid” economic recovery in China, this graph shows just how...

2/11

lop-sided and vulnerable this recovery has been. Before 2020, retail sales – which is a proxy for consumption, although it includes other things – had grown slightly faster than industrial production, suggesting a slow rebalancing in an economy that urgently needed to...

lop-sided and vulnerable this recovery has been. Before 2020, retail sales – which is a proxy for consumption, although it includes other things – had grown slightly faster than industrial production, suggesting a slow rebalancing in an economy that urgently needed to...

3/11

rebalance, but in 2020 that relationship has completely reversed, with industrial production growing so much faster than retail sales that it threatens to derail the last few years of limited rebalancing.

If the production side of the economy were the constraint in...

rebalance, but in 2020 that relationship has completely reversed, with industrial production growing so much faster than retail sales that it threatens to derail the last few years of limited rebalancing.

If the production side of the economy were the constraint in...

4/11

China’s economic growth, as it had been in the 1980s and 1990s, then it would be legitimate to conclude anyway that China had recovered. But even Beijing has publicly admitted for over a decade that the real constraint is the demand side of the economy, specifically...

China’s economic growth, as it had been in the 1980s and 1990s, then it would be legitimate to conclude anyway that China had recovered. But even Beijing has publicly admitted for over a decade that the real constraint is the demand side of the economy, specifically...

5/11

domestic consumption and the private sector investment driven by domestic consumption.

Not only have these barely recovered, but what many analysts are missing is that even this limited recovery has been driven by Beijing’s substantial boosting of the production side of...

domestic consumption and the private sector investment driven by domestic consumption.

Not only have these barely recovered, but what many analysts are missing is that even this limited recovery has been driven by Beijing’s substantial boosting of the production side of...

6/11

the economy. By expanding public sector investment in logistics and infrastructure, underwriting an expansion of credit to businesses, and otherwise subsidizing production, Beijing has bolstered production to create the employment that has indirectly boosted consumption...

the economy. By expanding public sector investment in logistics and infrastructure, underwriting an expansion of credit to businesses, and otherwise subsidizing production, Beijing has bolstered production to create the employment that has indirectly boosted consumption...

7/11

Put differently, economic recovery in China (and the world, more generally) requires a recovery in demand that pulls along with it a recovery in supply. But that isn’t what is happening. Instead Beijing is pushing hard on the supply side (mainly...

Put differently, economic recovery in China (and the world, more generally) requires a recovery in demand that pulls along with it a recovery in supply. But that isn’t what is happening. Instead Beijing is pushing hard on the supply side (mainly...

8/11

because it wants to lower unemployment as quickly as possible) in order to pull demand along with it. The problem with this strategy, as I have been writing since May, is that either it is resolved by a rapid increase in China’s trade surplus, which weakens the...

because it wants to lower unemployment as quickly as possible) in order to pull demand along with it. The problem with this strategy, as I have been writing since May, is that either it is resolved by a rapid increase in China’s trade surplus, which weakens the...

9/11

recovery abroad and forces an increase in foreign debt burdens, or it is resolved by faster growth in Chinese public-sector investment, which, because most of it is no longer productive, increases the Chinese debt burden. And this is exactly what we have been...

recovery abroad and forces an increase in foreign debt burdens, or it is resolved by faster growth in Chinese public-sector investment, which, because most of it is no longer productive, increases the Chinese debt burden. And this is exactly what we have been...

10/11

seeing in the data.

China’s “recovery”, in other words, is simply an exacerbation of the problems that have long been recognized. It isn’t sustainable, and unless Beijing moves quickly to redistribute domestic income, as I explain below, it will...

carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancial…

seeing in the data.

China’s “recovery”, in other words, is simply an exacerbation of the problems that have long been recognized. It isn’t sustainable, and unless Beijing moves quickly to redistribute domestic income, as I explain below, it will...

carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancial…

11/11

either require slower growth abroad or an eventual reversal of domestic growth once Chinese debt can no longer rise fast enough to hide the domestic demand problem.

either require slower growth abroad or an eventual reversal of domestic growth once Chinese debt can no longer rise fast enough to hide the domestic demand problem.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh