🧵Today, we (@IanPBeacock , @EseoheOjo, and I) are launching our new report and introducing the RAPID principles for how to put health communications at the heart of democracies’ response to Covid-19. (1 / 25)

democracy.arts.ubc.ca/2020/09/14/cov…

democracy.arts.ubc.ca/2020/09/14/cov…

We saw three problems:

1. many approaches to the pandemic neglect communications.

2. work was focusing more on the infodemic and less on how to create quality information.

3. the pandemic is intersecting with multiple crises in democracy. (2 / 25)

1. many approaches to the pandemic neglect communications.

2. work was focusing more on the infodemic and less on how to create quality information.

3. the pandemic is intersecting with multiple crises in democracy. (2 / 25)

Our report lays out a framework for how to communicate during a public health emergency in ways that strengthen democratic norms and processes rather than undermine them.

All the more important on @UN International Day of Democracy! (3 / 25)

All the more important on @UN International Day of Democracy! (3 / 25)

If communications are a health intervention, democratic communications can be a civic intervention. (4 / 25)

Our recommendations come from in-depth studies of nine jurisdictions and two provinces on five continents: Senegal, South Korea, Taiwan, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, New Zealand, and Canada (for which we also studied two provinces, British Columbia and Ontario). (5 / 25)

Each of the cases managed relatively effective responses on their own terms - each of them took democratic communications seriously. (6 / 25)

So what are the RAPID principles?

They are five broad principles that can underpin any democratic public health communications strategy. We call them the RAPID principles because rapidity is essential for an effective response. (7 / 25)

They are five broad principles that can underpin any democratic public health communications strategy. We call them the RAPID principles because rapidity is essential for an effective response. (7 / 25)

Rely on Autonomy, not Orders:

Pandemic responses should emphasize autonomy, where possible, in alignment with national traditions and local political cultures and supported by thoughtful and clear communications. (8 / 25)

Pandemic responses should emphasize autonomy, where possible, in alignment with national traditions and local political cultures and supported by thoughtful and clear communications. (8 / 25)

e.g. British Columbia issued guidelines but left many decisions up to local businesses or schools in consultation with work safety. Autonomy is not anarchy but rather a policy that includes stakeholders, assumes good faith, and reinforces democratic self-understanding. (9 / 25)

Attend to Emotions, Values, and Stories:

Facts alone are insufficient. Emotions, shared values and narratives build trust and make health information reliable. (10 / 25)

Facts alone are insufficient. Emotions, shared values and narratives build trust and make health information reliable. (10 / 25)

e.g. Taiwan framed physical distancing as an act of civic love; Senegal’s Ministry of Health shared stories of personal experiences on its social media. (11 / 25)

Effective communicators consider the diversity of the population, rely on pro-social hygiene and behavioural messaging. They articulate positive emotions like gratitude, acknowledge mental health struggles and seek to build rapport with citizens. (12 / 25)

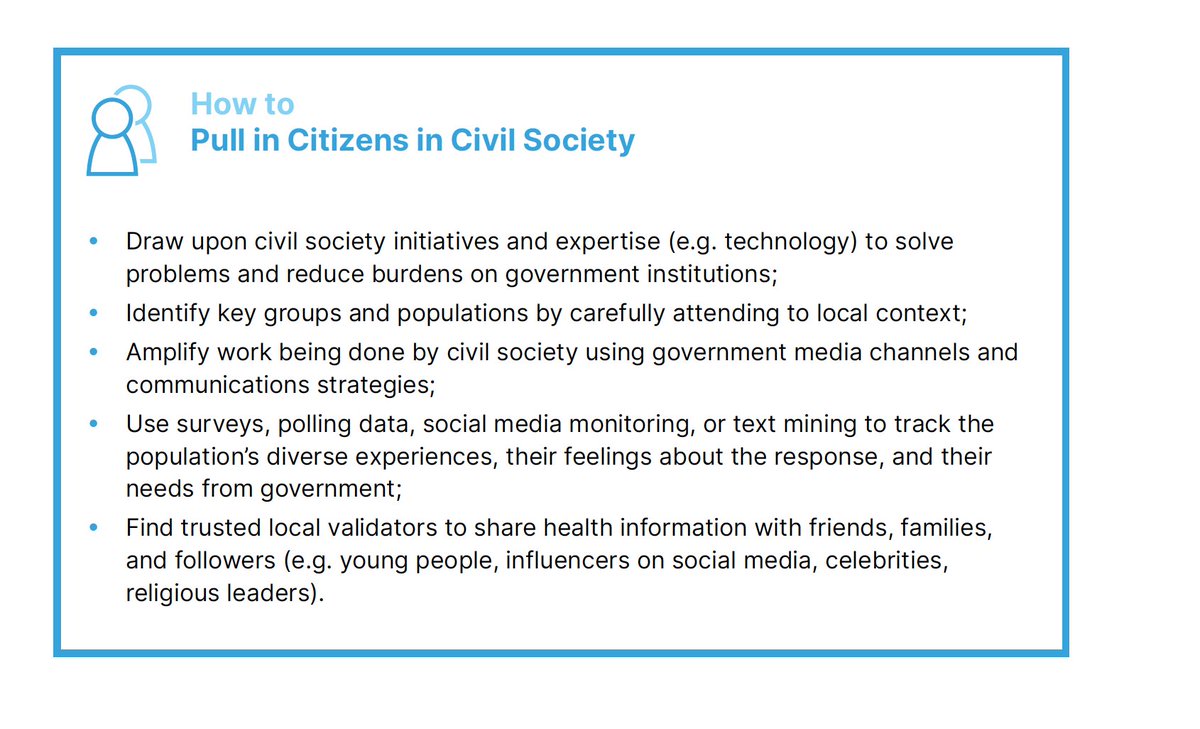

Pull in Citizens and Civil Society:

This should be at the heart of any strategy, not an afterthought. (13 / 25)

This should be at the heart of any strategy, not an afterthought. (13 / 25)

e.g. New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern “Conversations through Covid” talkshow series on Facebook included a children’s musician, female Indigenous scholars, and experts in mental health; Senegal cooperated with key religious leaders. (14 / 25)

Institutionalize Communications:

A communications unit creates the infrastructure to provide information swiftly during an outbreak.

e.g. South Korea’s CDC has an Office of Communication to get out info on multiple channels before rumours even started. (15 / 25)

A communications unit creates the infrastructure to provide information swiftly during an outbreak.

e.g. South Korea’s CDC has an Office of Communication to get out info on multiple channels before rumours even started. (15 / 25)

Describe it Democratically:

Democracy is about more than keeping parliaments running. Communicators also need to describe the pandemic democratically. (16 / 25)

Democracy is about more than keeping parliaments running. Communicators also need to describe the pandemic democratically. (16 / 25)

Avoid militaristic metaphors that limit room for agency and use more democratic metaphors that empower citizens. E.g. South Korea talked about a relay race; BC talks about Covid as a powerful storm. (17 / 25)

It is important to face the facts about Covid-19. There is no guarantee of an effective vaccine or even drug treatments.

Other pandemics will come. Since 2007, the WHO has declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) six times, including Covid-19. (18/25)

Other pandemics will come. Since 2007, the WHO has declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) six times, including Covid-19. (18/25)

Covid-19 is “a rehearsal for the really big pandemic, which I still believe is overdue,” - Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan @VivianBala (19 / 25)

Very few epidemics end with elimination. What is currently an epidemic disease may well become an endemic one. (20 / 25)

Even if we get effective treatments, non-pharmaceutical interventions like comms will remain critical for managing Covid-19.

But we have to consider how to make those comms democratic. Or we will worsen other ongoing crises of trust and institutions. (21 / 25)

But we have to consider how to make those comms democratic. Or we will worsen other ongoing crises of trust and institutions. (21 / 25)

Clear, consistent, compassionate, and contextual communications are essential during a time of crisis.

Public health depends on it.

The health of democracy does, too. (22 / 25)

Public health depends on it.

The health of democracy does, too. (22 / 25)

This research and report are supported by @WallInstitute, @ubcSPPGA, @UBCDemocracy and the Institute for European Studies.

We would also like to thank our generous collaborators and colleagues for their support @travissalway, @Yves_Global. (23 / 25)

We would also like to thank our generous collaborators and colleagues for their support @travissalway, @Yves_Global. (23 / 25)

Finally, in the difficult times of Covid, this project finds so many examples of kindness, smart governance, and compassion.

This team showed me that almost daily!

Thank you to the fab research team: @avickysituation, @yoojunglee_, @SudhaDavidWilp, @seancwu (24 / 25)

This team showed me that almost daily!

Thank you to the fab research team: @avickysituation, @yoojunglee_, @SudhaDavidWilp, @seancwu (24 / 25)

Special thanks to @seancwu who designed this beautiful report!

And the most heartfelt gratitude to my co-authors: @EseoheOjo and @IanPBeacock. I knew bringing together extraordinary people would make a great report but it's been truly such a joy. (25 / 25)

And the most heartfelt gratitude to my co-authors: @EseoheOjo and @IanPBeacock. I knew bringing together extraordinary people would make a great report but it's been truly such a joy. (25 / 25)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh