Today's @bopinion post attempts to answer the question: WTF happened in 1971???

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

2/The question is posed on this website, which is a giant series of charts showing a structural shift in the U.S. economy in the early 1970s.

wtfhappenedin1971.com

wtfhappenedin1971.com

3/Now, it's possible -- even likely? -- that MULTIPLE important things happened at the same time. There's not just going to be one answer.

But in this post, I focus on what I think was the single most important event: The oil shock of 1973.

But in this post, I focus on what I think was the single most important event: The oil shock of 1973.

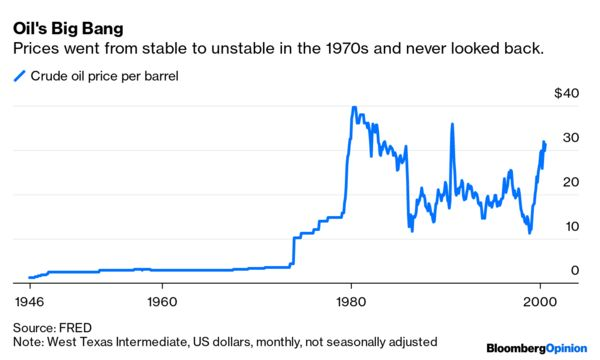

4/Today, it's hard for us to even realize what the age of Cheap Oil was like. Oil prices were very low and perfectly stable for decades.

Then one day: BAM. Everything changed.

Then one day: BAM. Everything changed.

5/One thing that probably caused was a 20-year-long productivity slowdown.

Economist William Nordhaus writes: "the energy shocks were the earthquake, and the industries with the largest slowdown were near the epicenter"

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Economist William Nordhaus writes: "the energy shocks were the earthquake, and the industries with the largest slowdown were near the epicenter"

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

6/More than just disrupting the economy, the oil shocks probably changed the TYPE of innovation we were able to do!

Before 1973, we just kept inventing bigger engines, faster transportation, more energy-hungry appliances.

Then suddenly we couldn't.

Before 1973, we just kept inventing bigger engines, faster transportation, more energy-hungry appliances.

Then suddenly we couldn't.

https://twitter.com/Ben_Reinhardt/status/1302660592419954688

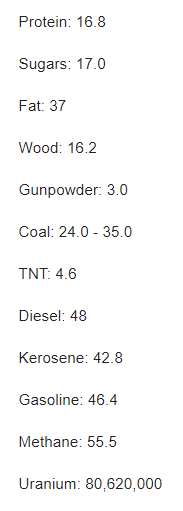

7/Our failure to progress from oil to something better also ended a centuries-long process of moving to denser and denser energy storage mediums.

noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/what-w…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_de…

noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/what-w…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_de…

8/We covered up this energy technology stagnation with super-cheap oil for a few decades, but 1973 brought that to a halt.

That pushed us from a world of "atoms" innovation to a world of "bits". And here we are today!

That pushed us from a world of "atoms" innovation to a world of "bits". And here we are today!

9/But of course, productivity was far from the only thing that slowed down in the early 70s.

Here's what happened to real wages. Note that 1973, not 1971, is where the crash begins.

Here's what happened to real wages. Note that 1973, not 1971, is where the crash begins.

10/Total compensation (including wages + benefits) didn't crash, but it did slow down. And it famously diverged from productivity beginning sometime in the early 70s.

11/Why did real wages fall?

Well, one clue might be found in the fact that NOMINAL wages didn't fall at all. They just kept on growing.

Meaning real wages fell because inflation rose and wages didn't keep up.

Well, one clue might be found in the fact that NOMINAL wages didn't fall at all. They just kept on growing.

Meaning real wages fell because inflation rose and wages didn't keep up.

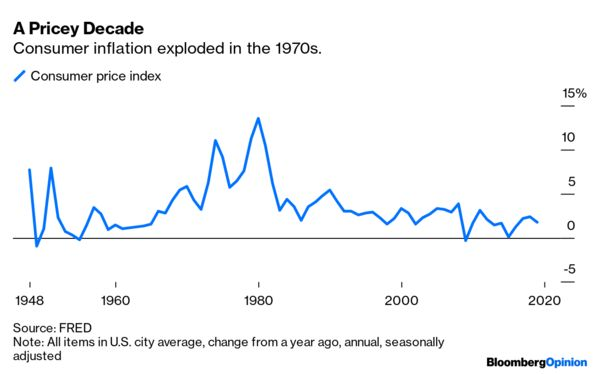

12/Inflation was rising in the late 60s, but workers were getting raises to compensate for it.

Then in the early 70s, inflation spiked much higher, and suddenly workers didn't get raises to keep up with inflation!

Then in the early 70s, inflation spiked much higher, and suddenly workers didn't get raises to keep up with inflation!

13/One reason might be that when the economy is doing well, tight labor markets allow workers to bargain for cost-of-living increases to keep pace with inflation, but when there's a recession -- like the one the Oil Crisis caused -- it prevents them from bargaining for raises.

14/Thus, stagflation -- recessions + inflation -- can be a toxic combo for wages.

Economists still argue over how much the Oil Crisis caused stagflation; Fed mistakes probably played a role as well. But the Oil Crisis was almost certainly the trigger.

frbsf.org/economic-resea…

Economists still argue over how much the Oil Crisis caused stagflation; Fed mistakes probably played a role as well. But the Oil Crisis was almost certainly the trigger.

frbsf.org/economic-resea…

15/The 70s stagflation led Jimmy Carter to appoint Paul Volcker, a tough inflation-fighter, to head the Fed. Volcker cured inflation but at the cost of 2 sharp recessions in the early 80s.

Those further reduced workers' bargaining power, holding down wages even more in the 80s.

Those further reduced workers' bargaining power, holding down wages even more in the 80s.

16/So both slowing productivity growth and falling wages -- the two big "WTF?" changes -- can plausibly be attributed to the Oil Crisis of the 1970s.

(Other big changes, like rising inequality and growing budget deficits and trade deficits, actually happened in the 80s.)

(Other big changes, like rising inequality and growing budget deficits and trade deficits, actually happened in the 80s.)

17/Now, as I said, a lot more was going on at the time. Union membership was declining.

But even this might have been impacted by the Oil Crisis; weaker bargaining power due to 70s recessions might have accelerated this decline.

But even this might have been impacted by the Oil Crisis; weaker bargaining power due to 70s recessions might have accelerated this decline.

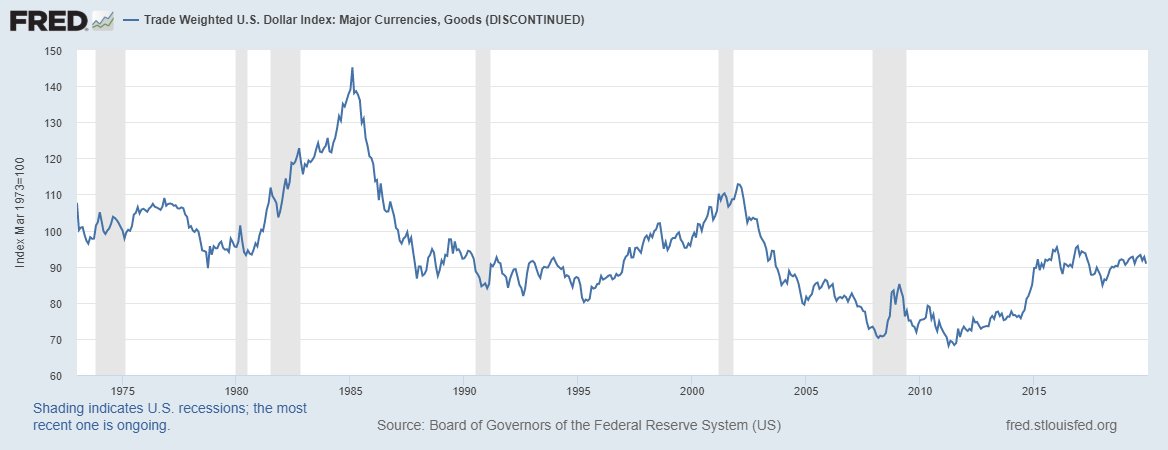

18/There was also a huge change in the international monetary system right around 1973: The end of Bretton Woods.

That could have had some effect too, but it's not as clear how that would have worked...

voxeu.org/article/operat…

That could have had some effect too, but it's not as clear how that would have worked...

voxeu.org/article/operat…

19/The U.S. dollar's strength didn't really change in the 70s, and a big trade deficit didn't open up til the 80s, so I'm inclined to think trade, and Bretton Woods, were not a big factor in the 70s shifts.

20/Really, I think the story of the 70s has to be first and foremost about oil. The end of the age of Cheap Oil, the end of centuries of energy tech improvements, and the resulting disruptions to an economy based on cheap energy.

(cc @natfriedman)

(cc @natfriedman)

21/BUT...here's the good news...We're in the middle of another energy technology revolution!

We didn't get nuclear power, but we are finally getting something that could be better than oil:

CHEAP SOLAR AND BATTERIES.

about.bnef.com/blog/scale-up-…

We didn't get nuclear power, but we are finally getting something that could be better than oil:

CHEAP SOLAR AND BATTERIES.

about.bnef.com/blog/scale-up-…

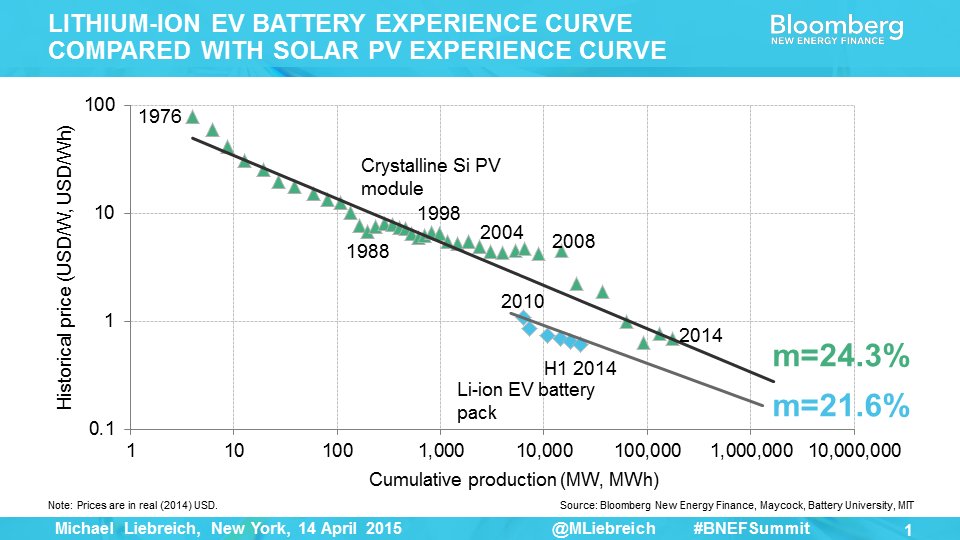

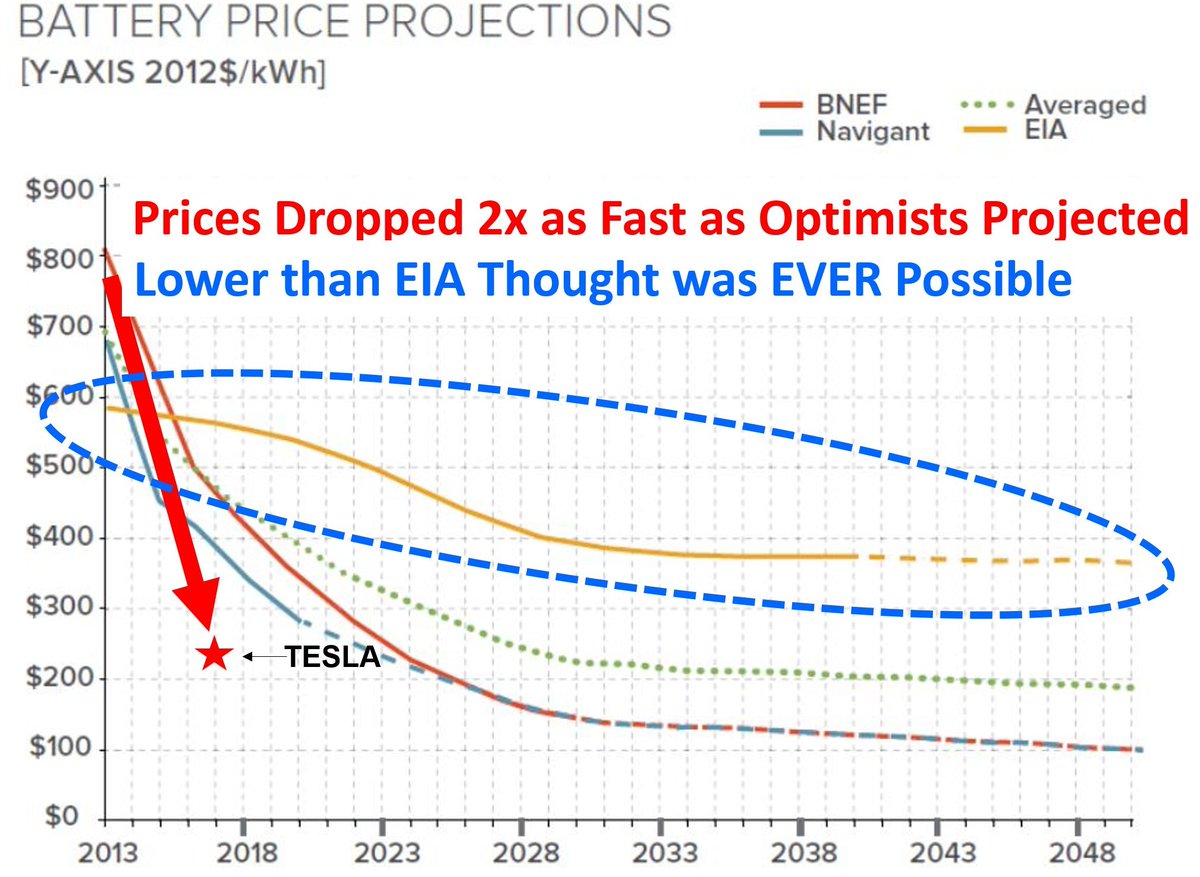

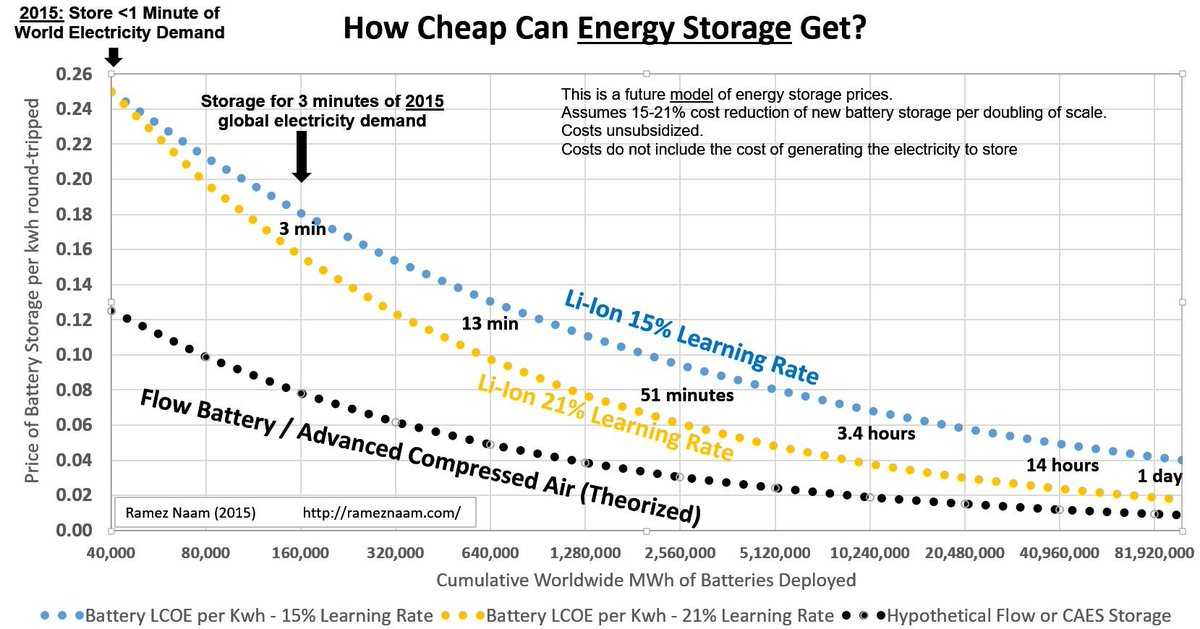

22/Here are some fun charts showing how cheap batteries are getting.

With a solar-powered (battery-storage-supported) electrical grid, this could finally bring back the age of Cheap Energy.

With a solar-powered (battery-storage-supported) electrical grid, this could finally bring back the age of Cheap Energy.

23/So we might finally be on the verge of innovating our way out of the hole that we fell into in the early 1970s.

That would be good news for the environment, but also potentially for wages, living standards, and human flourishing.

(end)

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

That would be good news for the environment, but also potentially for wages, living standards, and human flourishing.

(end)

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh