A second short thread on the Government’s proposed amendments to the Internal Market Bill — this time looking at what is said about judicial review. /…

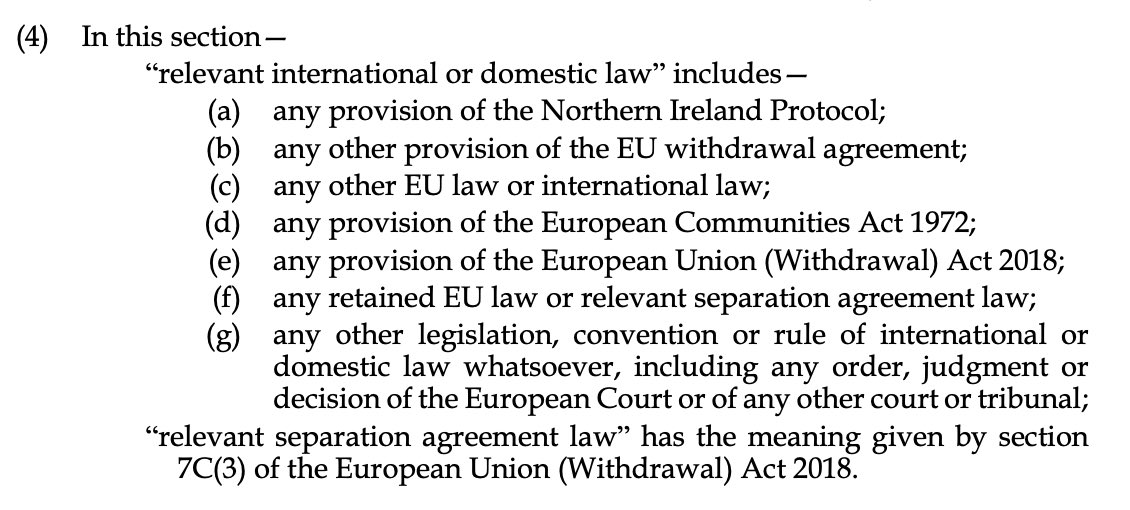

Clause 45 contains what has widely been taken to be an ouster clause, i.e. ousting the courts’ capacity to judicially review regulations made under clauses 42 & 43. They are given effect ‘notwithstanding’ incompatibility with a wide variety of forms of law. /…

In particular, the reference in clause 45(4) to ‘any rule of domestic law whatsoever’ seems, on the face of it, to rule out judicial review on normal grounds. /…

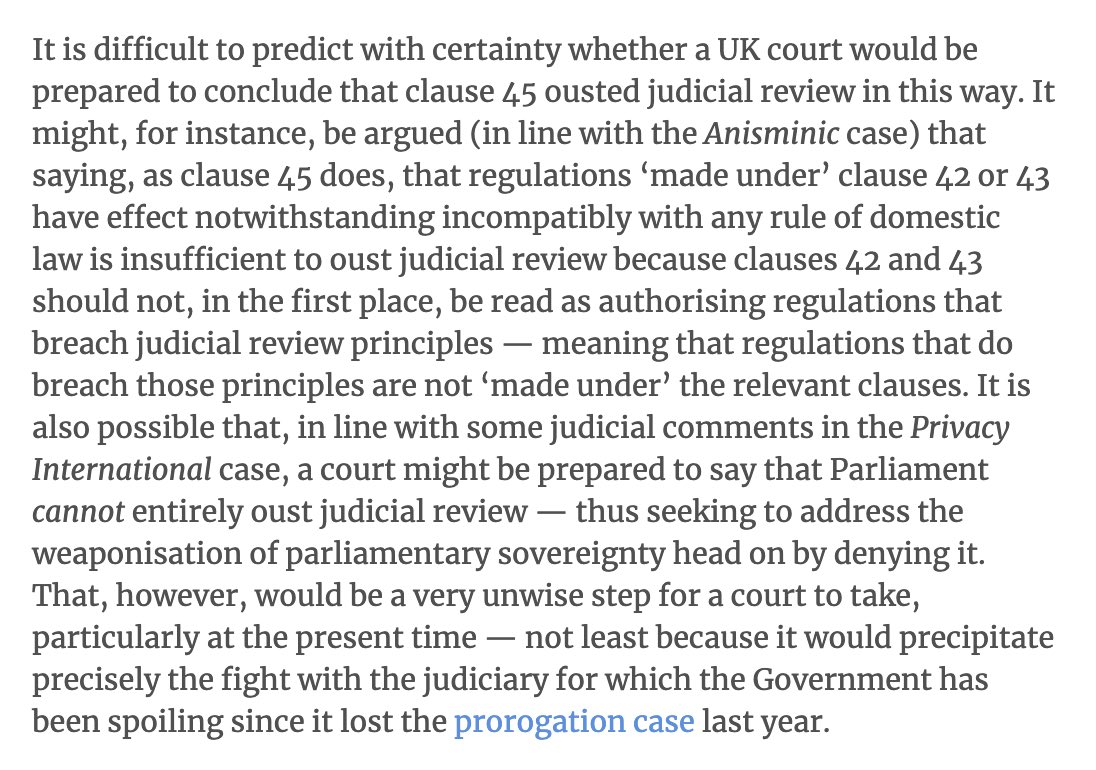

But placing Ministerial action, including regulations made by Ministers, beyond judicial review is a clear breach of the rule of law. A court would therefore seek, if at all possible, to preserve judicial review. /…

In a blogpost last week, I argued that there were two ways in which a court might approach this matter: either by means of (arguably strained) interpretation or by adopting the nuclear option of refusing to apply the ouster clause. /… publiclawforeveryone.com/2020/09/09/the…

@Jack_R_Williams also wrote about this in a very helpful piece on the @eurelationslaw blog. /… eurelationslaw.com/blog/clause-45…

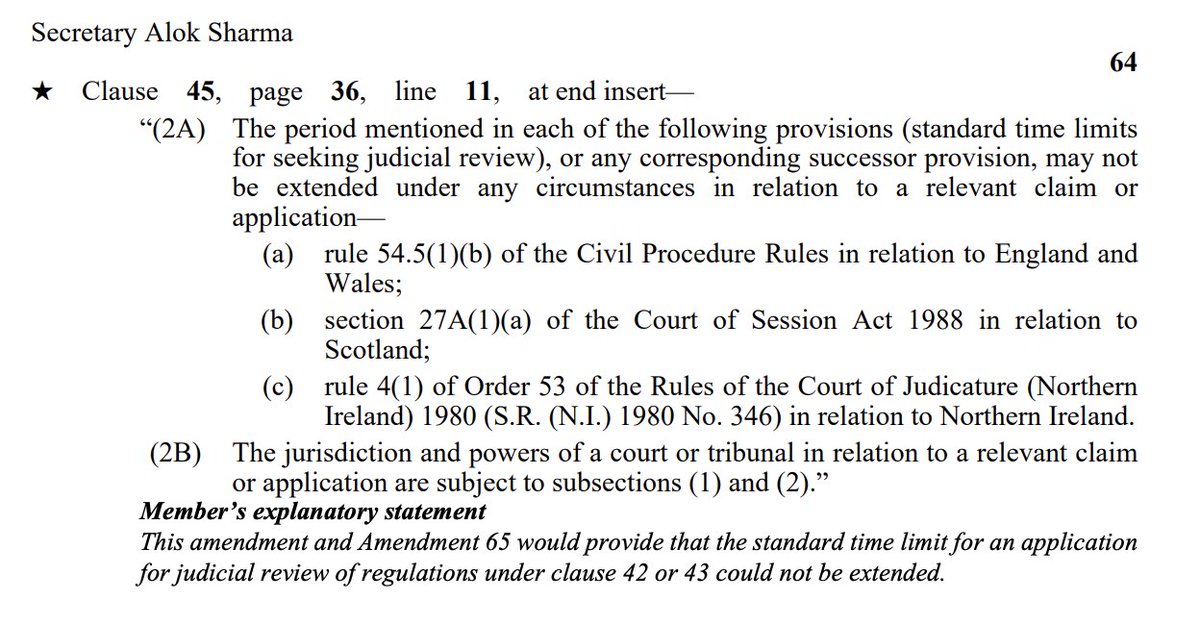

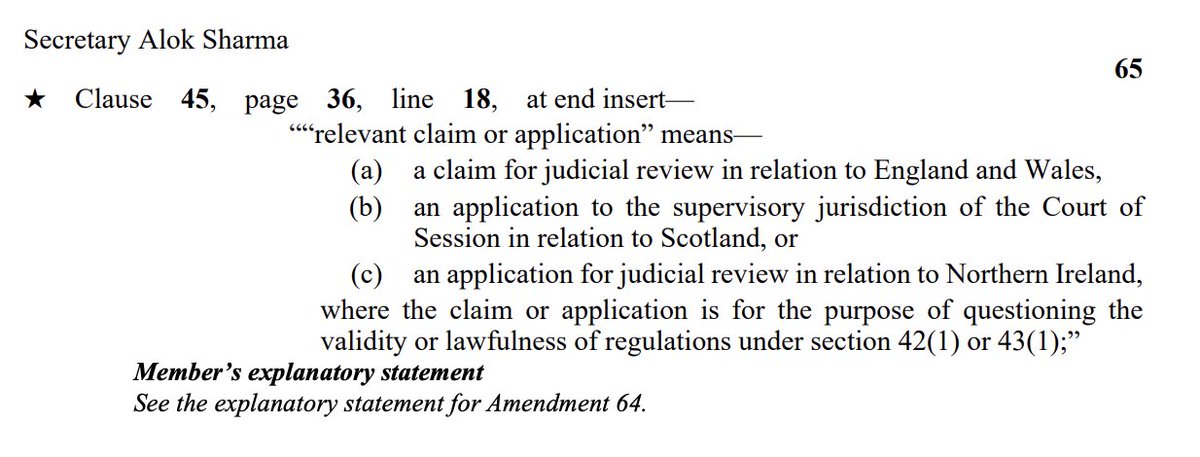

The effect of these amendments is to provide that the normal time limits for seeking judicial review cannot be extended when a court is asked to consider the validity of regulations made under clause 42 or 43. This clearly envisages that judicial review *will* be available /…

It is difficult to understand how the Government thinks this relates to the rest of clause 45 which, as noted, say that such regulations have effect even if they are incompatible with domestic, EU or international law. /…

The amendment contemplates courts ruling that clause 42/43 regulations are unlawful and invalid — yet clause 45(1) says that they ‘have effect’ even if incompatible with domestic, EU or international law. /…

One way of reconciling these points would be say that even if a court decided a regulation under clause 42/3 was unlawful and invalid it would nevertheless continue to ‘have effect’ because of clause 45(1). But the idea of effective invalid regulations is legally oxymoronic. /…

An alternative approach would be to adopt the approach I suggested in last week’s post, by saying that regulations are not ‘made under’ clause 42/3 if they breach judicial review principles, because clause 42/3 don’t in the first place authorise such regulations. /…

A further possibility is that a court might seek to reconcile the tensions within clause 45 as amended by holding that the reference to domestic law in clause 45 does not include the grounds of judicial review, thereby enabling sense to be made of the clause as a whole. /…

Either way, the amendments to clause 45 *are*, I think, a climb down of sorts, because they clearly contemplate the possibility of judicial review — even if the disjunction between the original clause and the amendments create a number of conceptual uncertainties. /ends

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh