Do you really know the story of the #BeninBronzes? Dan Hicks, whose new book I reviewed for @LAReviewofBooks, thinks museums have mythologized the story of the Punitive Expedition to conceal the ongoing violence of displaying the works: blog.lareviewofbooks.org/reviews/museum… (thread)

Hicks unearths the violent history of how approximately 10,000 objects were taken from Benin City, in what is now Nigeria, in the aftermath of an 1897 British Navy Punitive Expedition: plutobooks.com/9781786806840/…

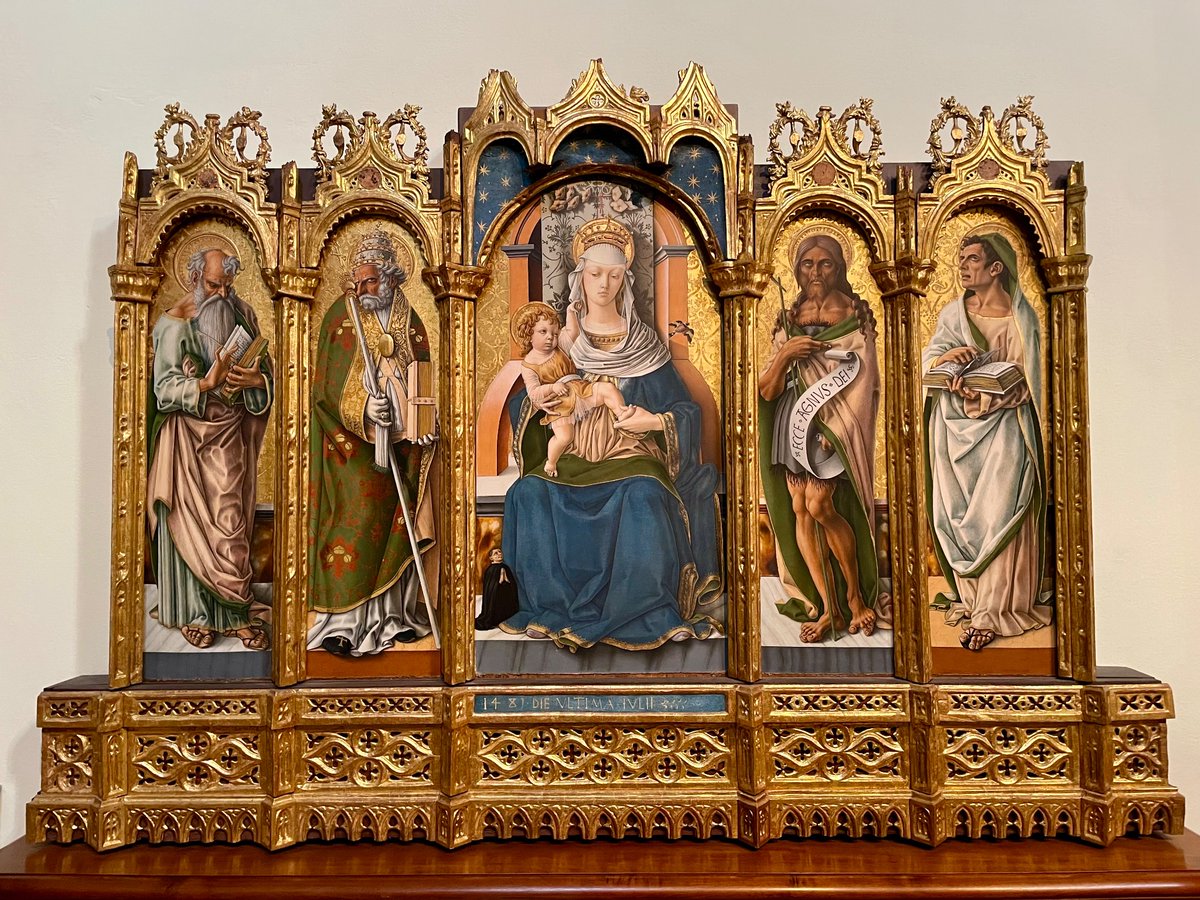

These artifacts, made over the course of 500 years, now in museums and private collections across the world, include many cast metal plaques and other sculptures, and so are known as the #BeninBronzes: weltmuseumwien.at/en/onlinecolle…

In Benin’s Edo language, the verb sa-e-y-ama means both “to cast a motif in metal” and “to remember.” In pre-literate Benin, the plaques were memory made material.

Although officially independent, Benin lay within Britain’s Niger Coast Protectorate, an administrative creation of the Colonial Office which was supposed to respect local sovereignty while defending the area from claims by other European powers.

After decades of failed attempts, Protectorate officials finally negotiated a trade treaty with Benin in 1892, so that “citizens of all countries may freely carry on trade in every part of the territories of the King.”

But less than two months after Oba Overami signed a treaty by marking an X, the Protectorate’s Consul General was writing to the British Prime Minister to tell him that the Oba had “paralyzed” commerce in the “very rich” Benin territory.

Supposedly, the Oba had used his religious authority to announce that trading was taboo for the commodities Britain desired: rubber and palm oil, which was important as a lubricant for the factories birthed by the Industrial Revolution.

The Oba could not be permitted to slow the wheels of British commerce. The Consul General doubted trade would be as open as desired without “a severe struggle, and a display, and probable use of force” to overthrow the Oba and undermine Benin’s religion as a whole.

This letter, as well as other evidence marshalled by Hicks, shows colonial administrators were thinking about using force to increase Britain’s profit nearly five years before the Punitive Expedition. But the death of James Phillips provided an eagerly seized excuse.

Phillips, the newly arrived Acting Consul for the Niger Coast Protectorate, informed the Prime Minister in late 1896 that the Oba was executing those who dared trade in palm kernels. (He might have been attempting to enforce tariffs on trade goods.)

In December 1896, Phillips set off to visit Benin City to ask the Oba to remove his trade restrictions. Phillips timed his visit for a festival when the Oba was in ritual isolation and was warned that any white man seeking to enter Benin City during this period would be killed.

Phillips persisted, and he was.

Two of the white men who accompanied Phillips escaped the attack on the road to Benin City, and the other six were either killed then or later, during the Punitive Expedition’s attack. Their 250 Kroo carriers were also either killed or taken captive.

Hicks makes a convincing argument that Phillips’ mission was designed to fail. The Protectorate could justify the force it already planned to use if the Oba refused to adhere to the treaty. Of course, Phillip’s death provided a vastly more magnificent excuse for deposing the Oba.

The Benin Punitive Expedition, which took place over 18 days in February 1897, took full advantage of British public outrage. It deployed 5,000 European and African soldiers and carriers in three simultaneous advances.

One column marched through the jungle from the coast toward Benin City, while two flotillas of warships and gunboats advanced up flanking waterways with the goal, as one participant put it in his memoir, to “increase the punishment inflicted on the nation.”

The sale of “arms of precision” had been prohibited within the Protectorate since 1893, so while Benin’s soldiers had flintlock guns and knives, the Punitive Expedition brought more than 3 million bullets to stock its 1,200 bolt-action rifles and more than 30 Maxim machine guns.

The flotillas were instructed to “destroy all towns” along their route. Hicks’ descriptions of machine guns spraying bullets “continually and indiscriminately” into the bush and of thousands of shells and rockets raining down on undefended settlements, recall Vietnam and Iraq.

Hicks also points to the ominous silence in British records of any mention of help for displaced, wounded, or captured Africans - and no attempt to total African losses (8 members of the Punitive Expedition were killed in action).

The silence of the records was deliberate. Authorities already knew that the British public didn't like the idea of machine guns mowing down armies fighting with medieval technology. There had been an outcry over the killing of 8,000 Zulu warriors in the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War.

The colonial authorities responded not by stopping massacres, but by stopping keeping records of them.

The Punitive Expedition was not satisfied with killing people. They also intended to kill a culture. The Expedition’s Chief of Staff’s to-do list after the taking of Benin City reads “Ju-Hu houses to blow down… Queen Mother’s house to be burnt.”

The Expedition destroyed Benin City’s mausoleums, hundreds of homes and administrative and religious buildings, and the artisan workshops that produced Benin’s splendor. Hicks calls this a deliberate “transformation of a living sacred and royal place into an archaeological site.”

Besides the plaques, they took the artwork decorating 35 ancestral shrines, one for each of the unbroken line of Obas who had ruled from 1440 onwards, and hundreds more statues, body ornaments, ceremonial objects, and carved ivory tusks.

The vast majority of Benin loot was handled by the white men who participated in the Expedition, who used it for personal profit. Within months, some of them had sold Benin loot to European museums, who rapidly put it on display.

And there, largely, it remains. Oba Akenzua II made the first formal request for repatriation of the loot in 1936. This, along with most other subsequent Nigerian calls for repatriation, was ignored.

Descendants of looters have voluntarily returned a few looted objects, but Nigeria has had to purchase the rest of the Benin objects it has on the open market (where they can sell for millions).

Diagnosing the Expedition’s “ultraviolence” as a malevolent instance of white fragility, where the avenging of an injury justified “the suspension of any normal moral codes,” Hicks erases any lingering sense of the fairness of Western museums keeping the Expedition’s loot.

Hicks also wants to explore what it means for Western museums to display #BeninBronzes. He posits that colonial-era anthropology museums were designed to set out concise visual arguments in support of anti-Black racism.

Displays of human skulls and photographs of "racial types" alongside “crude” artifacts reassured colonial citizens of their biological or cultural superiority - they shouldn't worry that their victories were due merely to the technological superiority of the machine gun.

Museums taught visitors that Africans were both other and less: alien minds in inferior bodies whose tendency toward violence could be controlled only through force.

Benin loot was displayed to illustrate an origin myth — a just-so story explaining why Africa deserved its punishment and subjugation.

Ethnographic displays operated in parallel with other galleries presenting the story of Western civilization. Oxford, for example, boasted two museums of archeology.

One, the Ashmolean Museum, held antiquities from Greece and Rome along with British works of art, making the claim that roots of British civilization could be traced back for many millennia.

In the Pitt Rivers Museum, on the other hand, visitors saw non-Classical antiquities from “primitive” cultures. The two museums presented two sets of ancestors: one to worship and the other to shun.

The British stole the objects from Benin’s ancestor shrines in order to decorate their own.

The louder the calls to repatriate the Bronzes become, the louder is the message of their continued display: the needs of the people who want the artifacts to leave the museum matter less than the needs of the people who want them to stay.

The signage in museums holding Benin Bronzes today generally mentions that Nigerians want them back. Hicks dismisses this as virtue-signaling - museums taking the opportunity to say that they care about the issue of colonial-era collecting without actually doing anything.

For Hicks, no amount of re-writing labels or “shuffling around of stolen objects in new displays that re-tell the history of empire” will prevent museums from repeating colonial violence “as long as a stolen object is present and no attempt is made to make a return.”

Just as the glorification of white supremacy on a Confederate monument still shines forth, no matter how many “contextualizing” signs might be clapped on its base, so, too, does the retention of the Bronzes continue to work to justify colonialism.

The Western public has played a crucial role in the fate first of Benin and then of the Bronzes. They were looted in part to teach the public a lesson, and the public has so far passively accepted that lesson. It is past time to change.

“Restitution is not subtraction,” Hicks argue, “it is refusing any longer to defend the indefensible.” The continued display of Benin loot is a continued violence.

Returning the Bronzes will not heal the wounds inflicted in their taking. But it will take the knife out.

Finally: so many thanks to my editor, @tyler_huxtable, for publishing a review which is just a teeny tiny bit way longer than what he's gotten from me in the past!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh