THREAD

1/

"When the facts change, I change my opinions. What do you do? - Attributed (without evidence) to John Maynard Keynes, hero of "How To Make The World Add Up" ch 10

Why is it so hard for people to change their minds?

1/

"When the facts change, I change my opinions. What do you do? - Attributed (without evidence) to John Maynard Keynes, hero of "How To Make The World Add Up" ch 10

Why is it so hard for people to change their minds?

2/ Partly, we make public statements and then we get stuck. We feel don't want to admit making a mistake. Opponents call us out for our inconsistency. A shame.

3/ But it should be really easy to update beliefs based on new information. For example, I wrote in August that the chance of being infected was 44 in a million per person per day. I still believe that is true.... of August.

Source: ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

Source: ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

4/ The chance then fell to 40/m/day. Then to 36/m/day. It doesn't require any enormous intellectual humility to say that in late August the invididual risk from the virus was falling.

The weekly ONS survey is published late each Friday morning: ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

The weekly ONS survey is published late each Friday morning: ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

5/ But then... the facts changed.

The weekly ONS prevalence survey showed 58 infections per million people per day. Then 110. (Doubling every 7 days? Not quite. But not far off.)

The weekly ONS prevalence survey showed 58 infections per million people per day. Then 110. (Doubling every 7 days? Not quite. But not far off.)

6/ New data due in a matter of minutes. I'll be paying attention. Alas the same cannot be said for Janet Street Porter, who writes in the Daily Mail...

7/ "Tim Harford, whose show More or Less on Radio 4 unpicks the truth behind statistics, has predicted that there's a 44-in-one million chance of getting infected with the virus in the UK if we act sensibly"

8/ Apart from the word "predicted" I can't argue with that. "Explained" or "reported" is the word I'd use. But that number is 5 weeks old. It's about to be 6 weeks old.

I'm really hoping that the prevalence survey flattens off, but that is a hope not an expectation.

I'm really hoping that the prevalence survey flattens off, but that is a hope not an expectation.

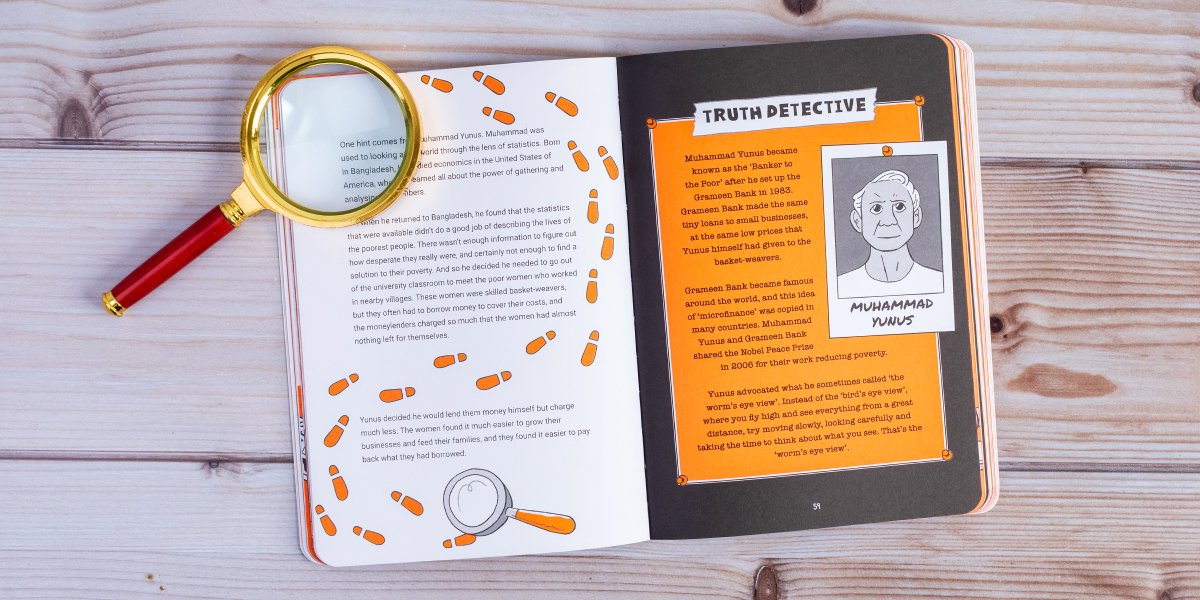

9/ This is an important idea from "How To Make The World Add Up". Are we using numbers to try to win an argument? Or are we using them to try to understand the world?

I want to understand the world - which is why we shouldn't ignore five weeks of data.

timharford.com/books/worldadd…

I want to understand the world - which is why we shouldn't ignore five weeks of data.

timharford.com/books/worldadd…

6b/ And the update is we're up to 175 cases per million people per day. Up 50% in a week. (The usual caveats apply: there's a broad margin of error and these results pertain to last week.)

ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh