Last evening a small back and forth btw @stephenniem and myself about the famed minaret of the mosque of Samarra made me wonder: hey, where did the idea come from that the minaret was inspired by ancient Sumerian ziggurats? They don't seem at similar at all!

A small THREAD

A small THREAD

When you go to Wikipedia, you can find this citation. Hmm, not so bold.

The citation comes from the second volume of Henri Stierlin's Comprendre l'Architecture Universelle, p. 347. I don't have access to this book, but it turns out that it's cited rather often.

The citation comes from the second volume of Henri Stierlin's Comprendre l'Architecture Universelle, p. 347. I don't have access to this book, but it turns out that it's cited rather often.

Delving a little deeper (and honestly, not too much), I found a reference in Kleiner's 2012 "Gardner's Art Through The Ages": "once thought to be an ancient Mesopotamian ziggurat, the Samarra minaret inspired some [...] depictions of the [...] Tower of Babel".

Kleiner's phrasing is much more careful, but doesn't say much where the equation of the Samarra minaret with Ziggurats began.

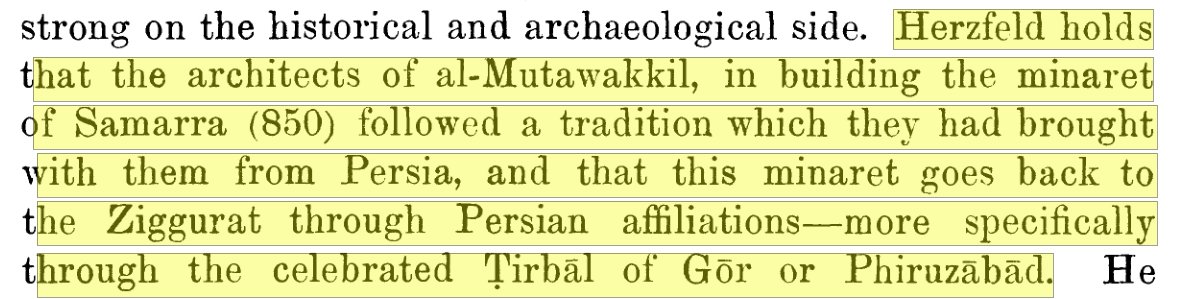

Gottheil, quoting Herzfeld, states that the Samarra minaret *might* go back to Ziggurats, but through Persian influence.

Gottheil, quoting Herzfeld, states that the Samarra minaret *might* go back to Ziggurats, but through Persian influence.

A connection btw the Samarra minaret and the tower at Firuzabad (pictured above) is more obvious than a (direct) link with Ziggurats.

A cursory glance at the Iranica page indicates that Herzfeld already pointed out that the Firuzabad tower does not descend from either.

A cursory glance at the Iranica page indicates that Herzfeld already pointed out that the Firuzabad tower does not descend from either.

So whence the connection with Ziggurats? I think there's a development from "wide minaret, like the Ziggurat" to "wide Ziggurat-like minaret" to "descended from minarets".

And such descriptions pop up more often in popular travelogues and pseudo-science than in academia.

And such descriptions pop up more often in popular travelogues and pseudo-science than in academia.

For example, note the description of famously insane writer Harold T. Wilkins', mostly known for his outlandish (outwaterish?) ideas about Atlantis:

Annie Abernethie Quibell who, apart from having an amazingly British name, went even further. In her 1925 travel book "A Wayfarer in Egypt", she states the minaret of Samarra is an "obvious descendant of the old Babylonian ziggurat".

One more? Ok, one more.

This is from Sir Edgar T.A. Wigram's (again, extremely British) The Cradle of Mankind – Life in Eastern Kurdistan (p. 348). Sadly, he neglects to provide any footnotes, so I cannot check his apparent sources; maybe he just made this up.

This is from Sir Edgar T.A. Wigram's (again, extremely British) The Cradle of Mankind – Life in Eastern Kurdistan (p. 348). Sadly, he neglects to provide any footnotes, so I cannot check his apparent sources; maybe he just made this up.

(What's rather sad about this description is that it rather clearly diminishes the contribution of the Abbasids: rather than acknowledge the Abbasids' capability of creating structures in their own right, Wigram states they "merely" preserved it).

These descriptions give the impression that (fictional) relationship to the Sumerian and Babylonian ziggurats came from popular writers, who misinterpreted academics (geez, what's new), and used "ziggurat" as a cool shorthand for old buildings in Mesopotamia in general

END

END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh