This 📷 is the ruins of Hattusa, capital of the Hittite Empire in the #BronzeAge. Tax collectors there amassed a fortune in grain, hundreds of tonnes of which are still inside!

Here's an #AntiquityThread on what the largest find of its kind tells us about ancient politics 🧵 1/

Here's an #AntiquityThread on what the largest find of its kind tells us about ancient politics 🧵 1/

Hattusa was established as by Hattusili I ~1650BC. The Hittite Empire would go on to rule most of Anatolia within a few centuries, coming into conflict with Assyrians and the New Kingdom of Egypt. 2/

📷: Map of the Hittite Empire at its greatest extent by Ikonact / CC BY-SA 3.0

📷: Map of the Hittite Empire at its greatest extent by Ikonact / CC BY-SA 3.0

A big empire needs a big granary and archaeologists uncovered one at Hattusa in 1999. It's over 100 metres long and could hold ~6,0000 tonnes of grain - enough to feed a population of 20 000–30 000 for one year! 3/

📷: Plan of the grannery.

📷: Plan of the grannery.

What makes this find especially incredible is hundreds of tonnes of this grain was still in place, preserved as a charred mass >1 metre thick 4/

📷: A mass of carbonised cereals above the stone floor of the granary

📷: A mass of carbonised cereals above the stone floor of the granary

This charring was the result of a fire that appears to have taken place shortly after the silo was built and the structure was abandoned.

But whilst this was bad news for the Hittites it's great for archaeologists, as it preserved the grain for study 5/

But whilst this was bad news for the Hittites it's great for archaeologists, as it preserved the grain for study 5/

The rulers of Hattusa likely filled this giant granary with taxation. People would have to give a portion of their produce, calculated from their agricultural output and

labour force.

Except for the elites, they were exempt. 6/

labour force.

Except for the elites, they were exempt. 6/

Thanks to this granary, we can see how the regular folk under Hittite rule fulfilled their demands.

The secret? Focusing on low-effort cereals that produced reasonable returns, even under marginal conditions. 7/

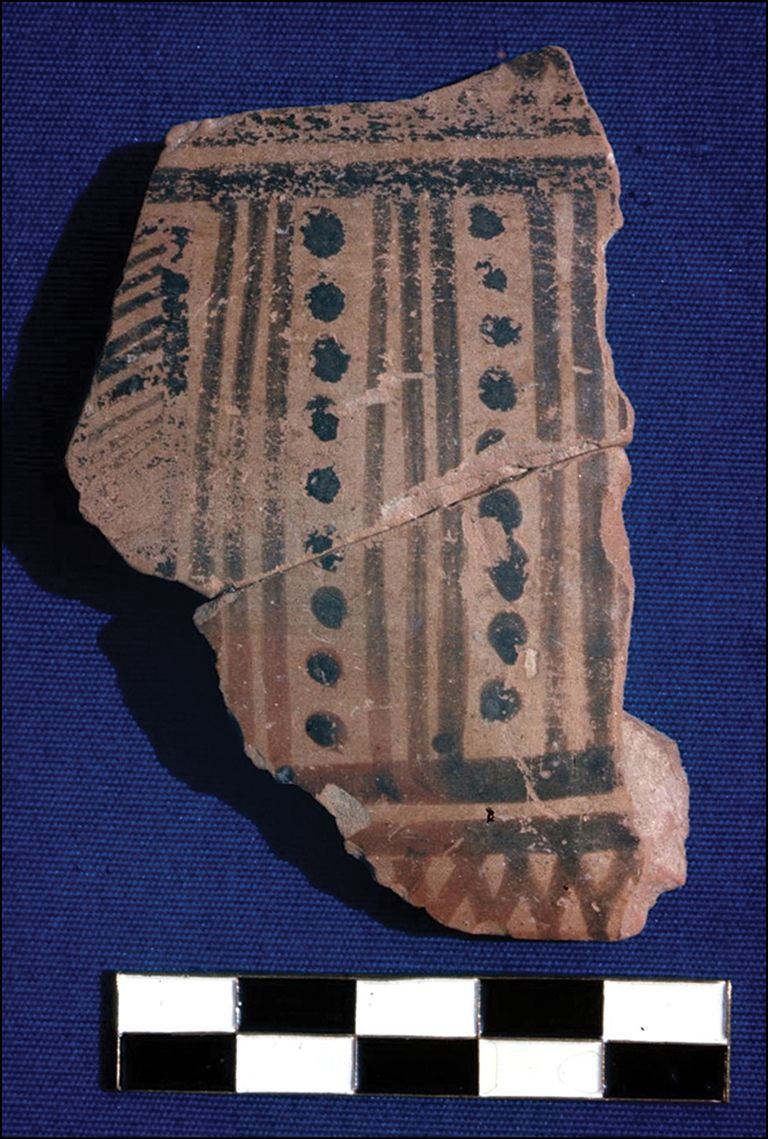

📷: Wheat & barley recovered from the silo.

The secret? Focusing on low-effort cereals that produced reasonable returns, even under marginal conditions. 7/

📷: Wheat & barley recovered from the silo.

But there was some variation in this strategy, likely dictated by the land farmers had access too.

The ability of the royal administration to tax such a range of people across a wide area suggests the tax collector had a long reach even back then. 8/8

The ability of the royal administration to tax such a range of people across a wide area suggests the tax collector had a long reach even back then. 8/8

Read more about the analysis of the largest archaeobotanical assemblage in the world in the original research in Antiquity 👇

Diffey, Neef, Seeher & Bogaard. The agroecology of an early state: New results from Hattusha (£) doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

Diffey, Neef, Seeher & Bogaard. The agroecology of an early state: New results from Hattusha (£) doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh