One of the standard issues with going to swarming or mob programming is always "How will we spot the bad programmers then? How will we catch the people who are loafing? How will we spot underskilled people if they don't do individual work?"

I went as far as to add it to my slide deck when I am teaching whole-team structures. It is going to come up anyway, and people are usually glad it's already in the topics list.

Of course, the first thing I say is "I don't know. I've not seen it yet. Swarms seem to keep everyone involved and interested pretty much all the time." This is true. It's hard for people to believe.

This suggests that either it doesn't happen, or they're REALLY good at hiding in groups. ;-)

The other thing I ask is how they managed to hire bad programmers who don't want to work.

Were they this bad when they were hired?

How long have you had them on staff without catching them so far?

Were they this bad when they were hired?

How long have you had them on staff without catching them so far?

And, of course, how are you sure that there ARE any bad programmers? Considering your rigorous hiring guidelines and the accelerated schedules you've had, why do you think that you must have loafers, slackers, and losers in your teams? Maybe everyone is pretty good?

I often am told that it's human nature, that anyone given the chance to get paid for doing nothing will happily do so. But this isn't what I've observed: developers WANT to develop. They WANT to solve problems. They WANT to ship code.

Self-motivation is common.

but...

Self-motivation is common.

but...

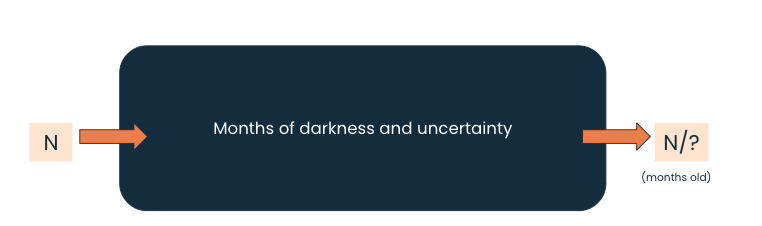

... the other things I've seen is that people can be tired and demotivated if they've been pushed hard to do work that is beneath their ability ("don't design, don't test, don't learn, just hack") for a long time.

They don't loaf though; they rest.

They might back off a bit.

They don't loaf though; they rest.

They might back off a bit.

After having a moment to recover, though, I tend to find them eager to get into meaty, complex, interesting work and often are surprisingly driven.

You probably don't have any bad people working for you.

They may be frustrated or exhausted and they may need a break. That's okay, work is hard sometimes.

I wouldn't insist on calling them "bad" or "spent."

They may be frustrated or exhausted and they may need a break. That's okay, work is hard sometimes.

I wouldn't insist on calling them "bad" or "spent."

Here, again, I suspect we might want to suspend judgment and exercise curiosity.

What if you don't have any bad people?

What would you do instead of rooting them out and firing them?

What if you don't have any bad people?

What would you do instead of rooting them out and firing them?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh