1/10

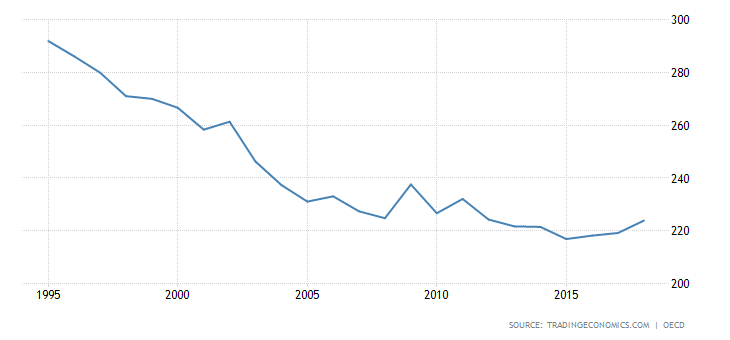

I agree, Adam, that what happened in Japan is a very important story, but I would add that your graph shows Japanese government debt, which is only half the debt story. In the 1980s, when Japan was still growing quickly, private-sector debt grew more rapidly than...

I agree, Adam, that what happened in Japan is a very important story, but I would add that your graph shows Japanese government debt, which is only half the debt story. In the 1980s, when Japan was still growing quickly, private-sector debt grew more rapidly than...

https://twitter.com/adam_tooze/status/1311784909137227785

2/10

Japanese government debt. In the 1990s, however, when Japanese GDP growth had pretty much dropped to zero, private-sector debt began to shrink as a share of GDP, just as government debt began its rapid growth.

tradingeconomics.com/japan/private-…

Japanese government debt. In the 1990s, however, when Japanese GDP growth had pretty much dropped to zero, private-sector debt began to shrink as a share of GDP, just as government debt began its rapid growth.

tradingeconomics.com/japan/private-…

3/10

I think, in other words, that while there was growth in Japanese debt after 1990-92, there was also a lot of shifting of debt from private-sector to government balance sheets. The reason I think this is important is because of what it might tell us about China.

I think, in other words, that while there was growth in Japanese debt after 1990-92, there was also a lot of shifting of debt from private-sector to government balance sheets. The reason I think this is important is because of what it might tell us about China.

4/10

Until the early 1990s Japanese GDP growth – which was unbalanced towards investment rather than consumption, although not nearly to China's extent – had become heavily reliant on rising private and public sector debt. Because in the late 1980s much of this went to fund...

Until the early 1990s Japanese GDP growth – which was unbalanced towards investment rather than consumption, although not nearly to China's extent – had become heavily reliant on rising private and public sector debt. Because in the late 1980s much of this went to fund...

5/10

non-productive investment, the country's total debt-to-GDP ratio began to grow rapidly (when debt is used to fund productive investment, debt grows, but debt to GDP doesn't).

Once the growth in Japanese debt began to reach limits in the early 1990s, however, GDP mostly...

non-productive investment, the country's total debt-to-GDP ratio began to grow rapidly (when debt is used to fund productive investment, debt grows, but debt to GDP doesn't).

Once the growth in Japanese debt began to reach limits in the early 1990s, however, GDP mostly...

6/10

stopped growing.

After that Japan partially rebalanced at the same time that debt shifted from private-sector balance sheets to public-sector balance sheets. I think these two were related. The effective shifting of debt from private to public balance sheets may have...

stopped growing.

After that Japan partially rebalanced at the same time that debt shifted from private-sector balance sheets to public-sector balance sheets. I think these two were related. The effective shifting of debt from private to public balance sheets may have...

7/10

been one way that income shifted to households. Their income grew more slowly than GDP before 1990s but more quickly after, which is perhaps why the collapse in Japanese GDP growth never seemed to bother Japanese households as much as you might otherwise have expected.

been one way that income shifted to households. Their income grew more slowly than GDP before 1990s but more quickly after, which is perhaps why the collapse in Japanese GDP growth never seemed to bother Japanese households as much as you might otherwise have expected.

8/10

The implication for China is that it can maintain rapid GDP growth only as long as debt can rise much faster than GDP, but once the growth in debt slows, GDP growth must drop sharply. So far this probably isn't controversial, but what is more complicated is...

The implication for China is that it can maintain rapid GDP growth only as long as debt can rise much faster than GDP, but once the growth in debt slows, GDP growth must drop sharply. So far this probably isn't controversial, but what is more complicated is...

9/10

to understand what will happen next. Japan, I think, represents one way China can evolve, with a long period of very low growth as it shifts, rather than resolves, the debt burden.

In the end resolving the debt burden just means recognizing and allocating...

to understand what will happen next. Japan, I think, represents one way China can evolve, with a long period of very low growth as it shifts, rather than resolves, the debt burden.

In the end resolving the debt burden just means recognizing and allocating...

10/10

the costs of writing it down, which is politically painful. Shifting it onto government balance sheets is a way of spreading out the allocation of costs over a very long period, although this may come at the cost of much slower growth.

the costs of writing it down, which is politically painful. Shifting it onto government balance sheets is a way of spreading out the allocation of costs over a very long period, although this may come at the cost of much slower growth.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh