Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London.

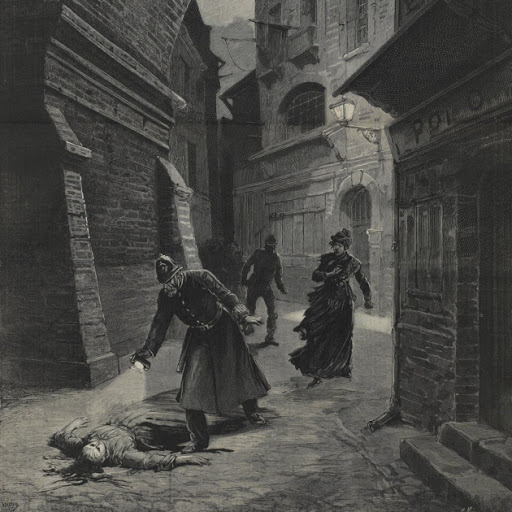

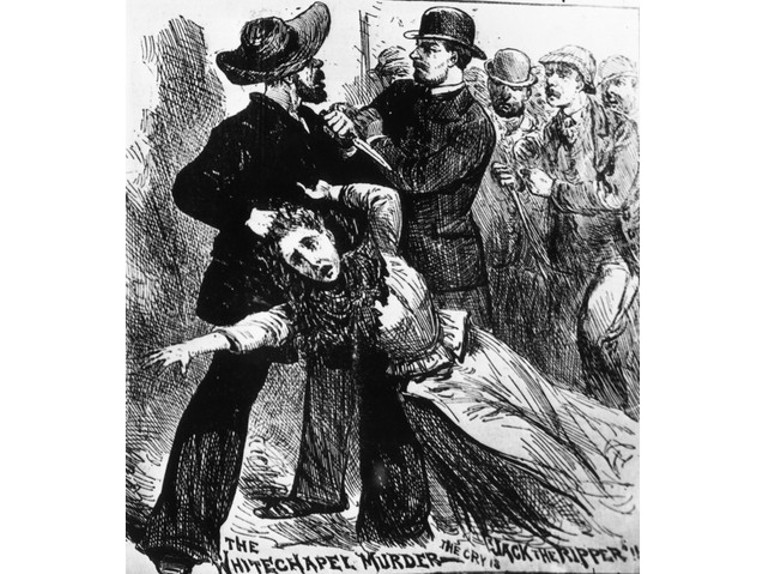

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums of the East End of London whose throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations.

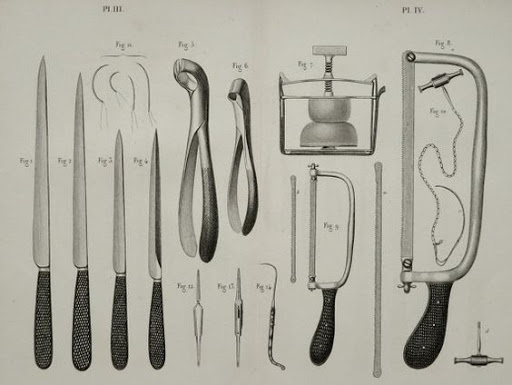

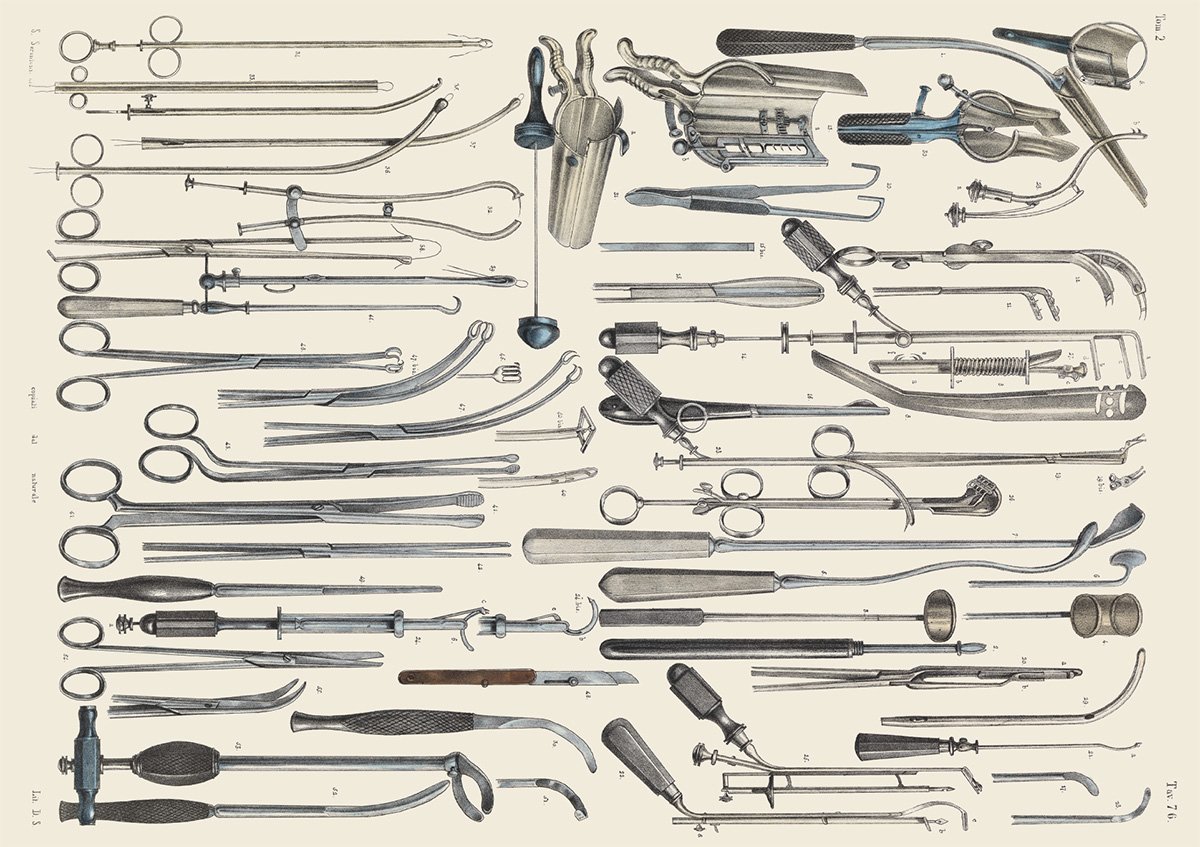

The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to proposals that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge.

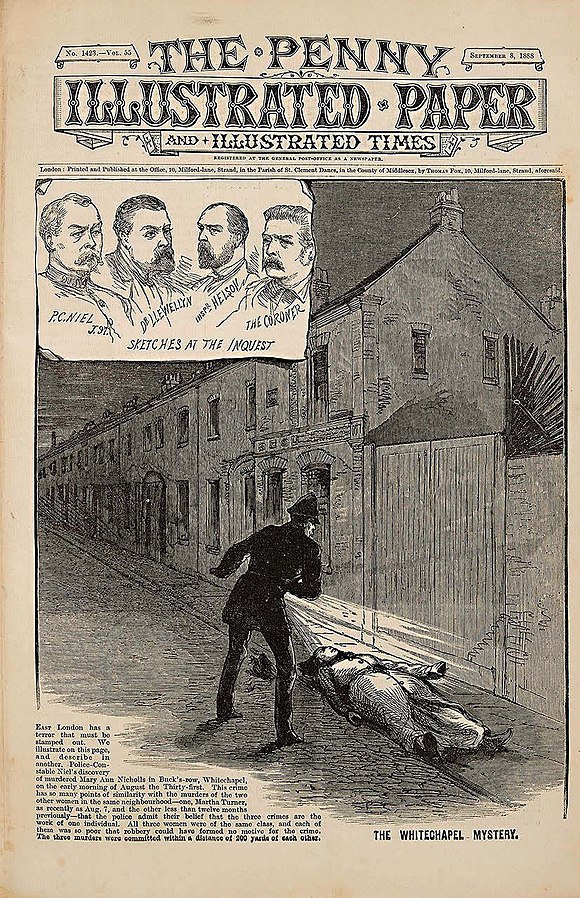

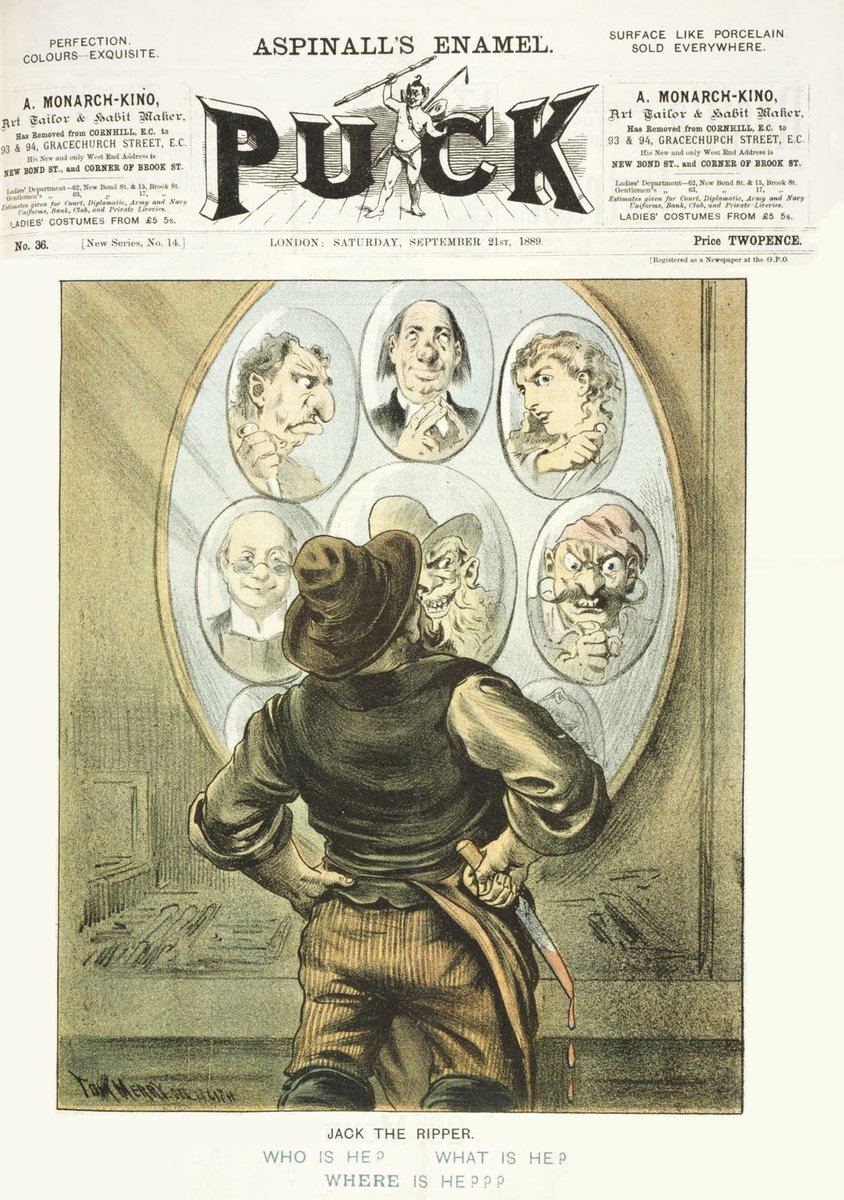

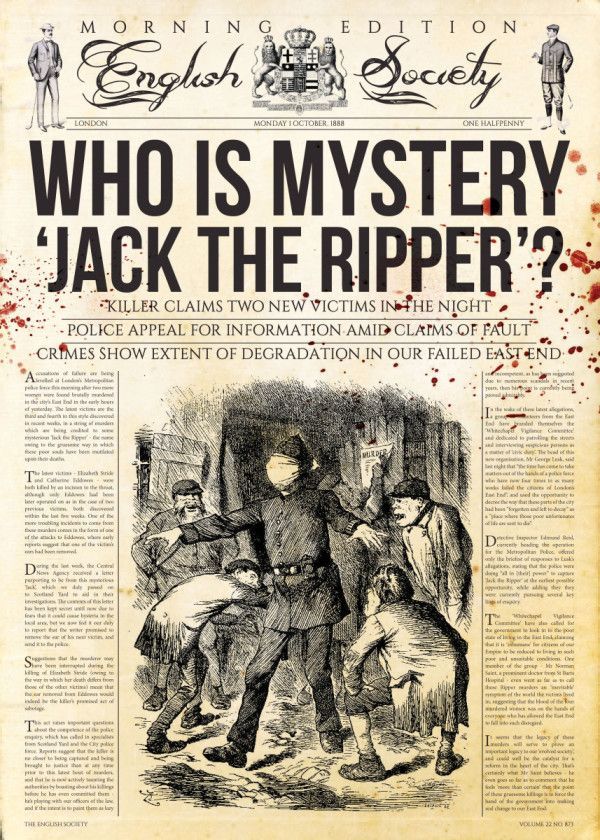

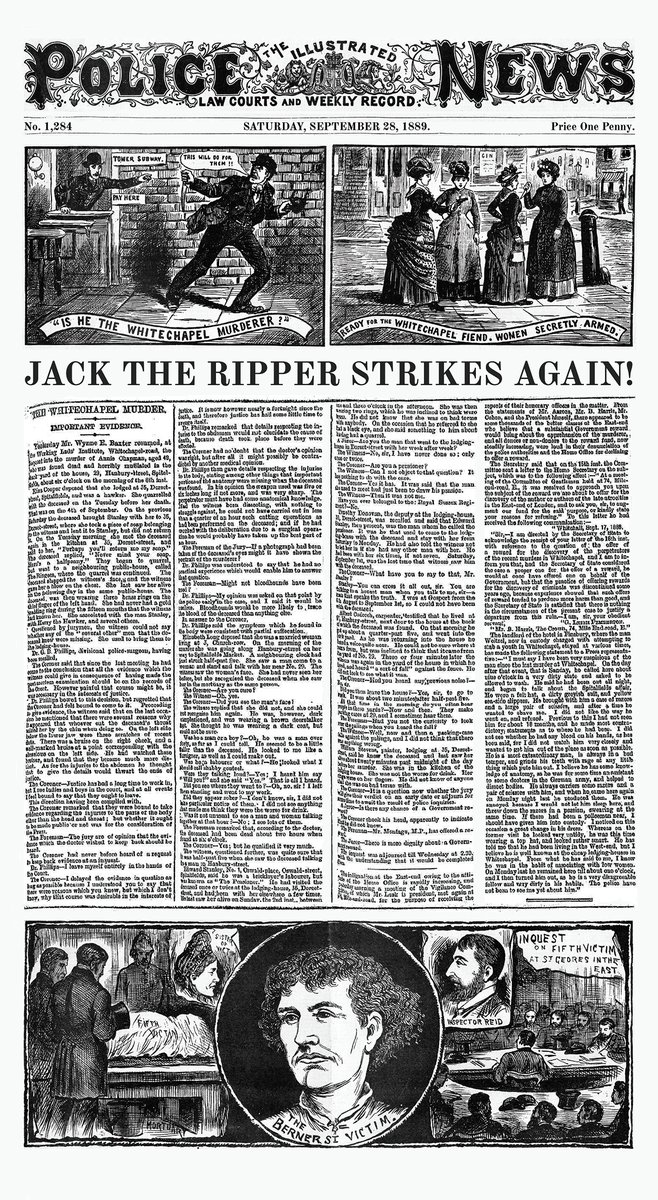

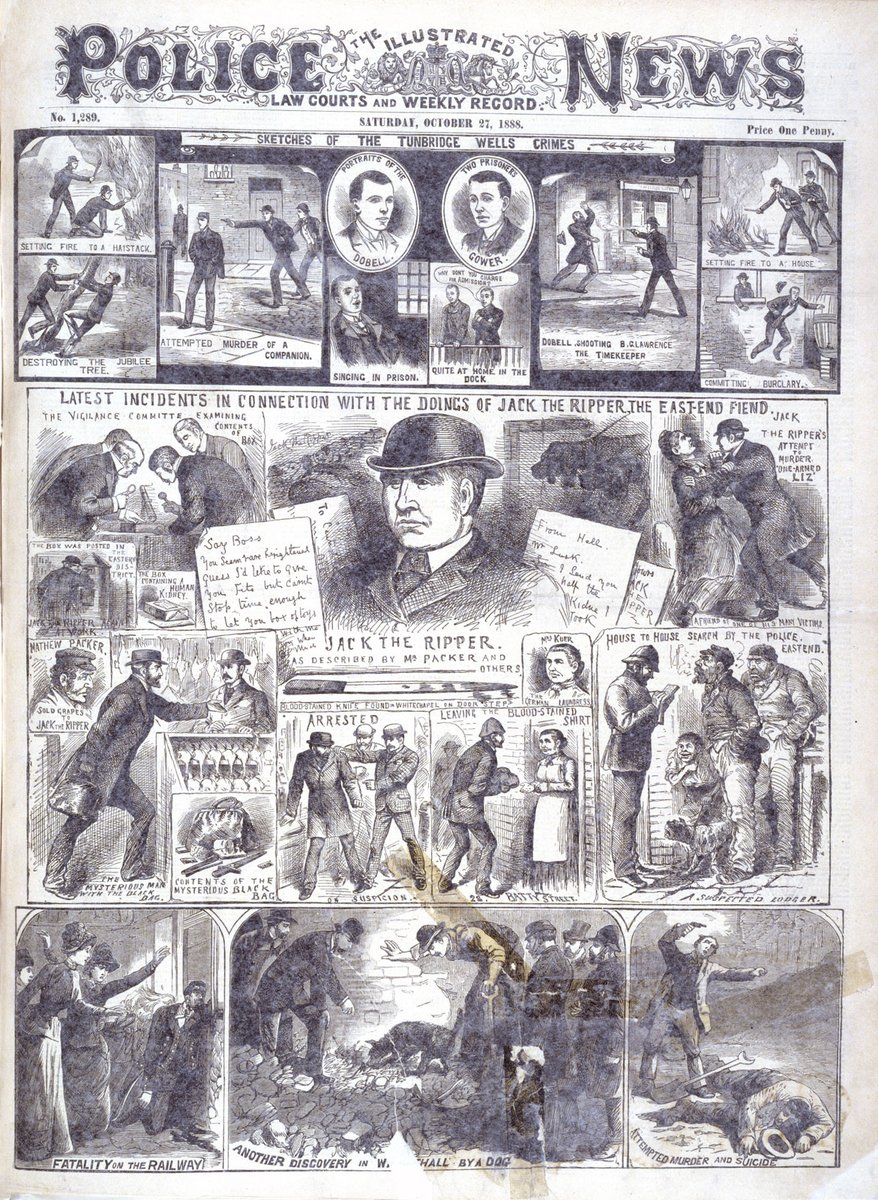

Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and numerous letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard from individuals purporting to be the murderer.

The public came increasingly to believe in a single serial killer known as "Jack the Ripper", mainly because of both the extraordinarily brutal nature of the murders, and media coverage of the crimes.

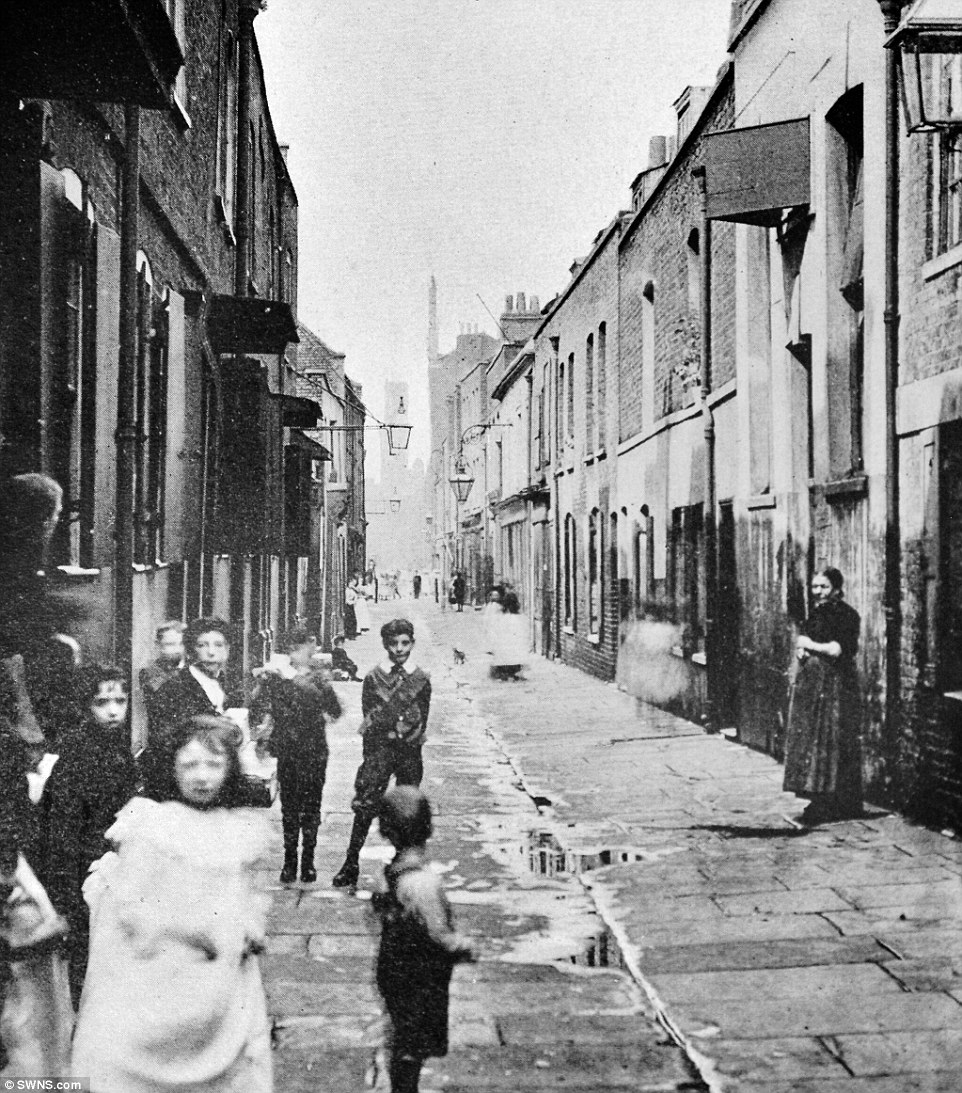

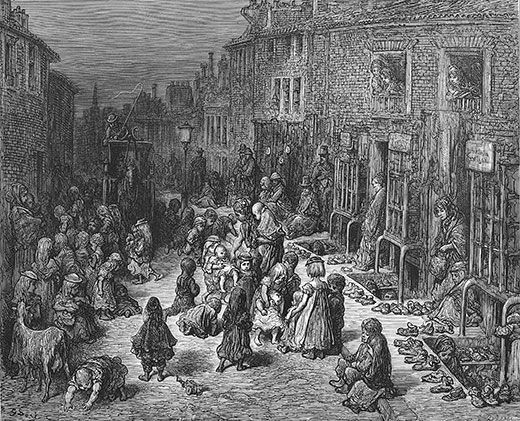

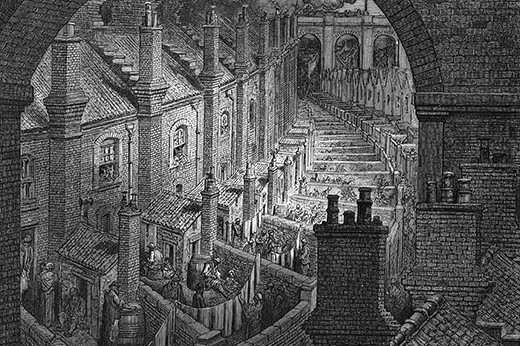

In the mid-19th century, Britain experienced an influx of Irish immigrants who swelled the populations of the major cities, including the East End of London.

From 1882, Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in Tsarist Russia and other areas of Eastern Europe emigrated into the same area.

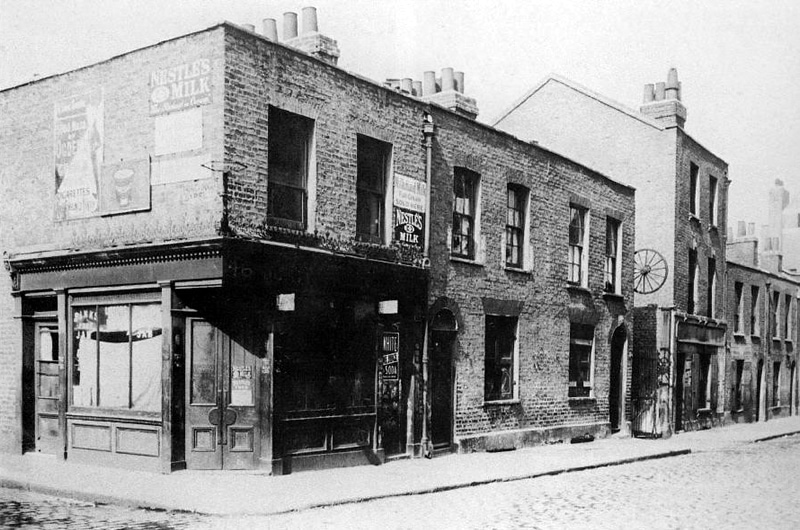

The parish of Whitechapel in London's East End became increasingly overcrowded, with the population increasing to approximately 80,000 inhabitants by 1888.

Work and housing conditions worsened, and a significant economic underclass developed. Fifty-five percent of children born in the East End died before they were five years old.

Robbery, violence, and alcohol dependency were commonplace, and the endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution to survive on a daily basis.

In October 1888, London's Metropolitan Police Service estimated that there were 62 brothels and 1,200 women working as prostitutes in Whitechapel

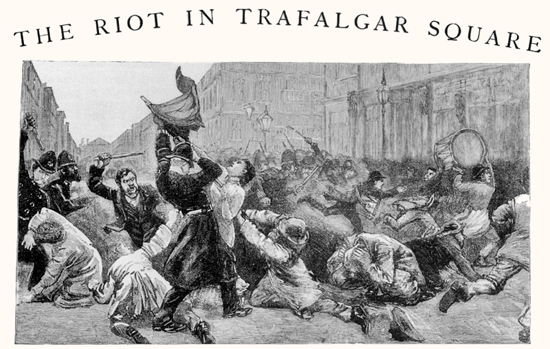

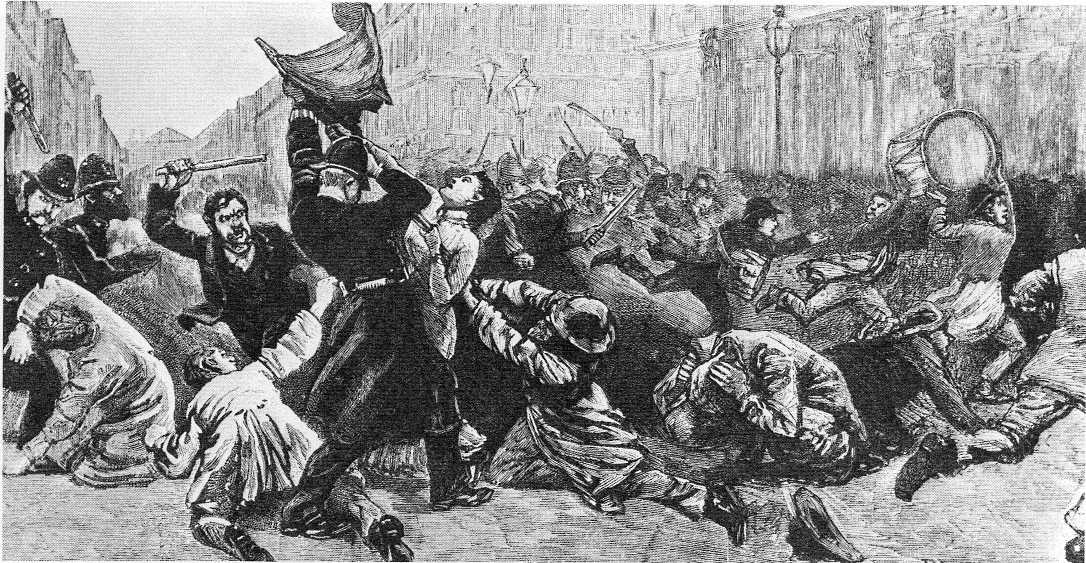

The economic problems in Whitechapel were accompanied by a steady rise in social tensions. Between 1886 and 1889, frequent demonstrations led to police intervention and public unrest, such as Bloody Sunday (1887).

Anti-semitism, crime, nativism, racism, social disturbance, and severe deprivation influenced public perceptions that Whitechapel was a notorious den of immorality.

Such perceptions were strengthened in the autumn of 1888 when the series of vicious and grotesque murders attributed to "Jack the Ripper" received unprecedented coverage in the media.

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were murdered by the same individual.

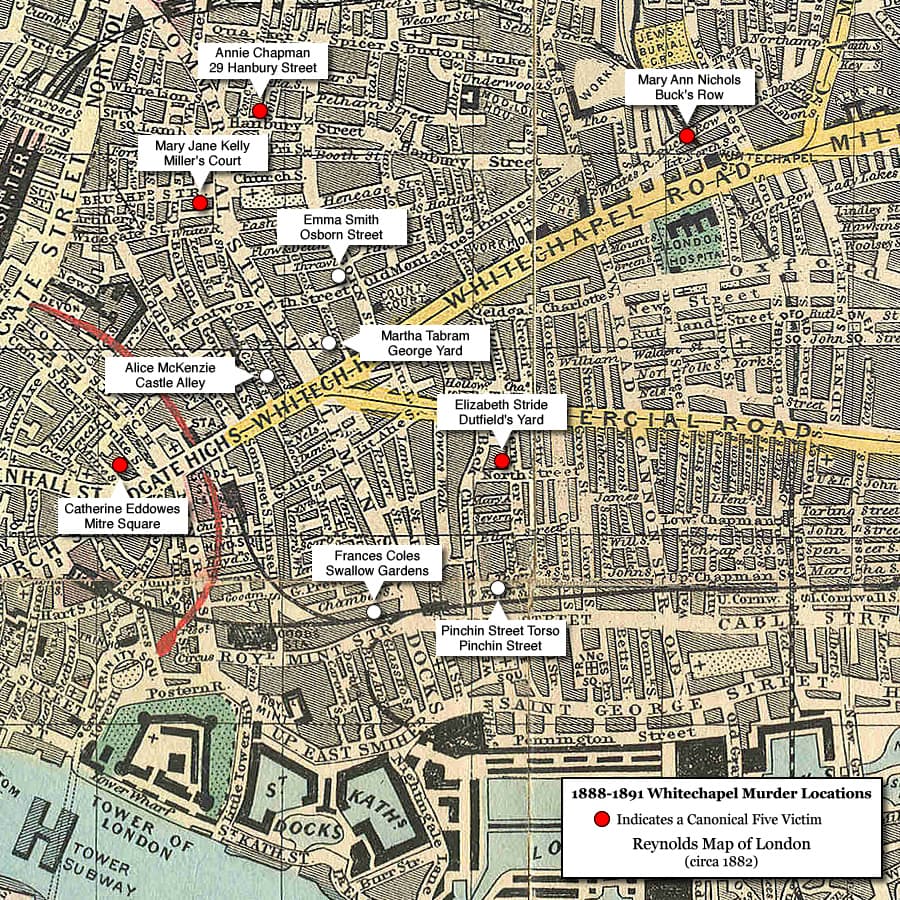

Eleven separate murders, stretching from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, were included in a London Metropolitan Police Service investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders".

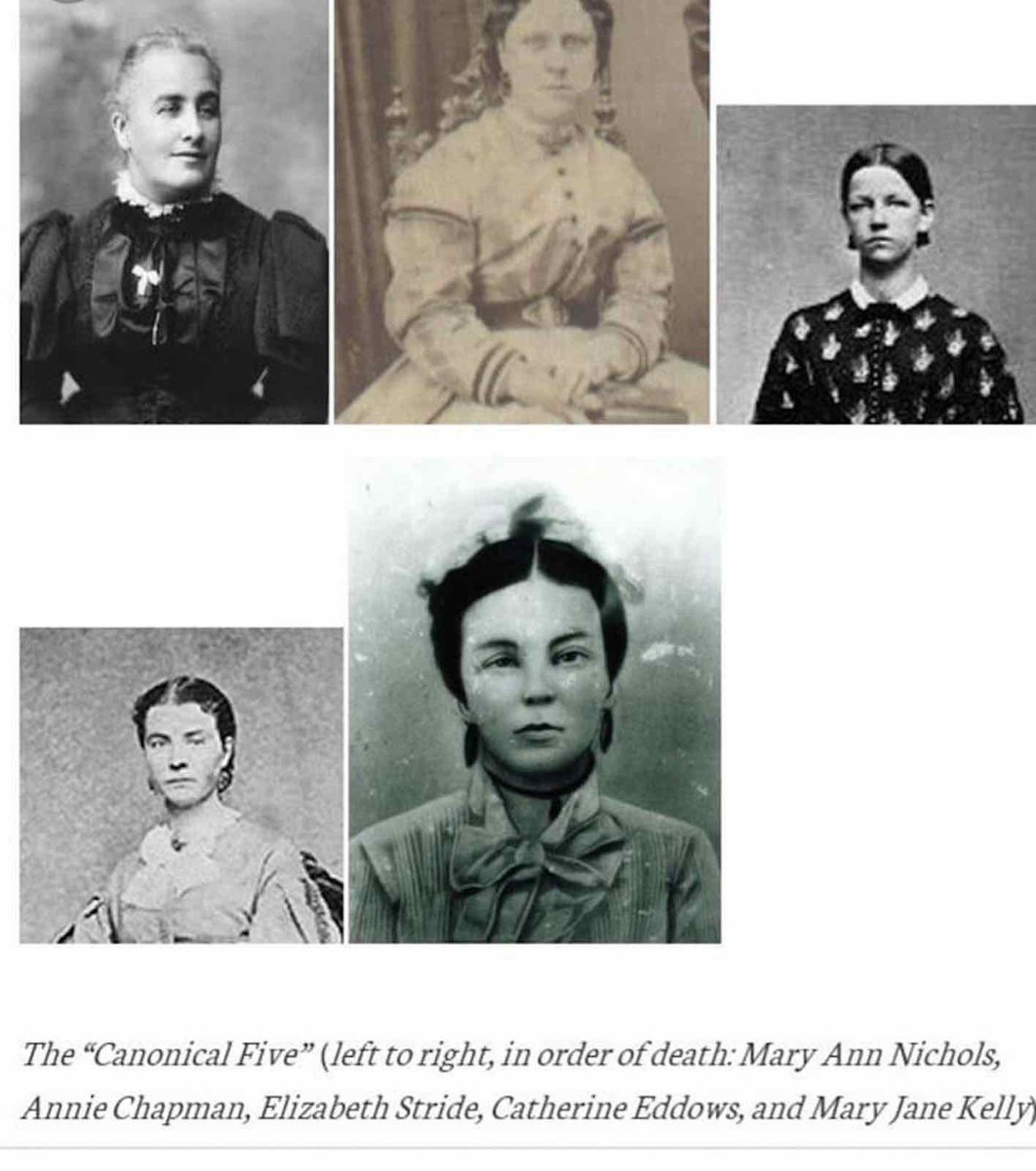

Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the "canonical five", are widely believed to be the work of Jack the Ripper

Most experts point to deep slash wounds to the throat, followed by extensive abdominal and genital-area mutilation, the removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of the Ripper's modus operandi.

The first two cases in the Whitechapel murders file, those of Emma Elizabeth Smith and Martha Tabram, are not included in the canonical five.

Smith was robbed and sexually assaulted in Osborn Street, Whitechapel, at approximately 1:30 a.m. on 3 April 1888. She had been bludgeoned about the face and received a cut to her ear.

A blunt object was also inserted into her vagina, rupturing her peritoneum. She developed peritonitis and died the following day at London Hospital.

Smith stated that she had been attacked by two or three men, one of whom she described as a teenager.

This attack was linked to the later murders by the press, but most authors attribute Smith's murder to general East End gang violence unrelated to the Ripper case

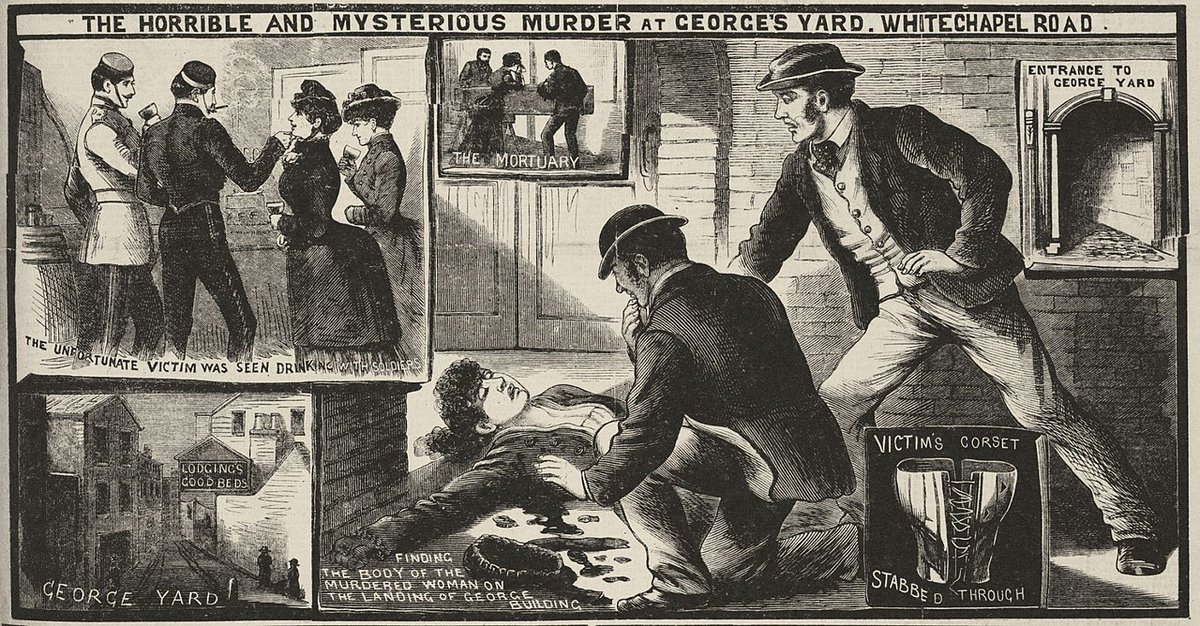

Tabram was murdered on a staircase landing in George Yard, Whitechapel, on 7 August 1888; she had suffered 39 stab wounds to her throat, lungs, heart, liver, spleen, stomach, and abdomen, with additional knife wounds inflicted to her breasts and vagina

The savagery of this murder, the lack of an obvious motive, and the closeness of the location and date to the later canonical Ripper murders led police to link this murder to those later committed by Jack the Ripper.

However, this murder differs from the later canonical murders because although Tabram had been repeatedly stabbed, she had not suffered any slash wounds to her throat or abdomen.

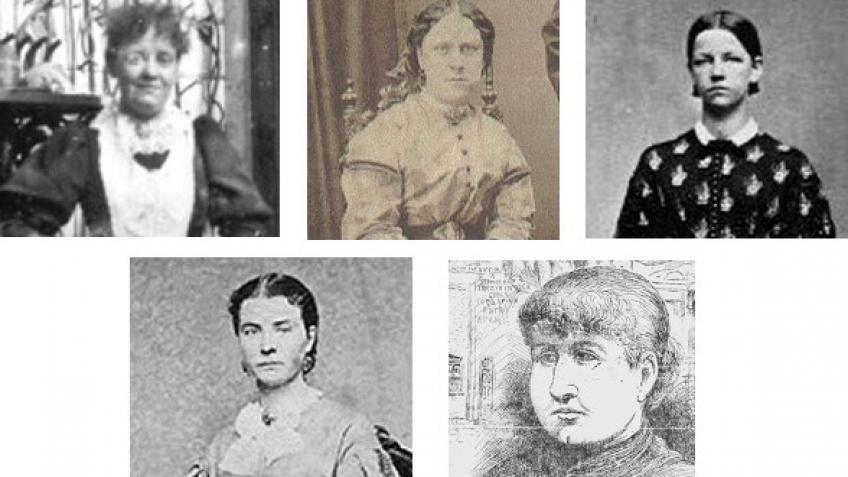

The canonical five Ripper victims are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly

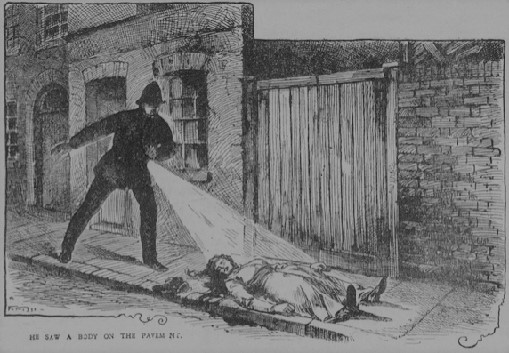

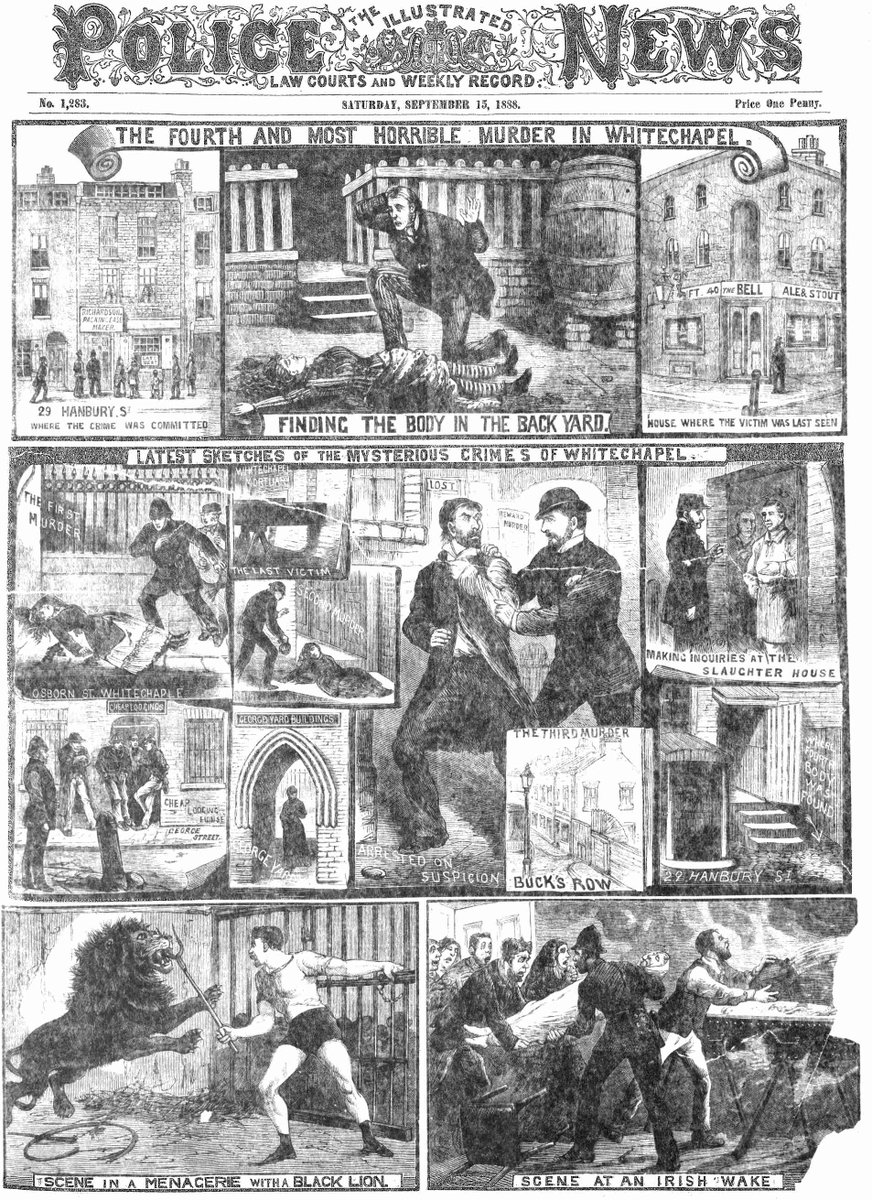

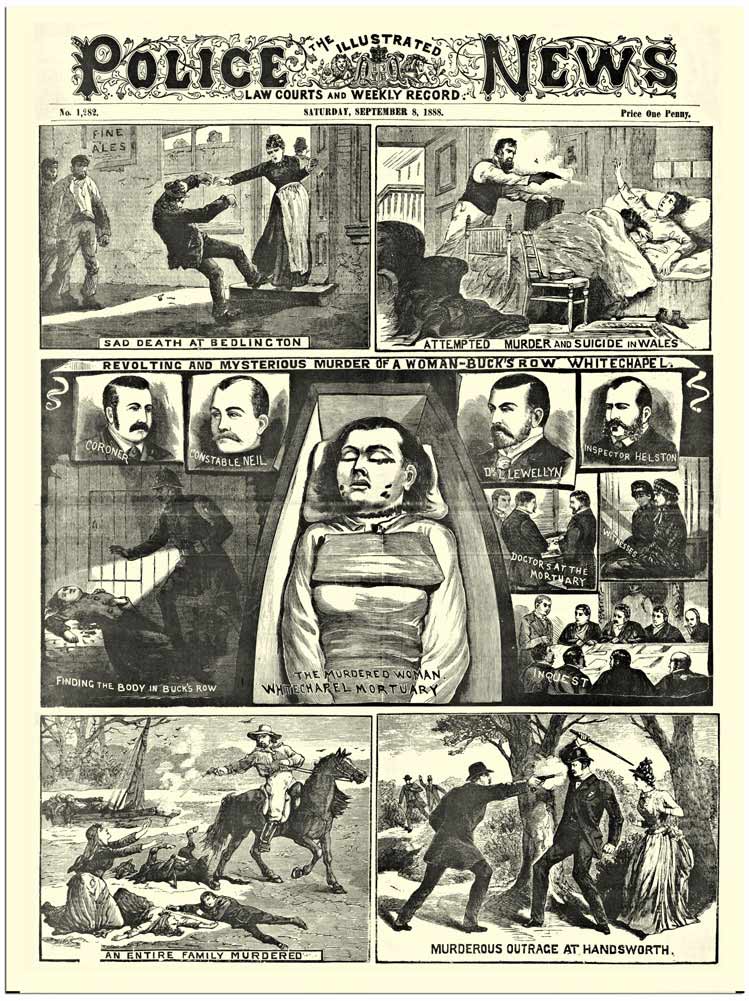

The body of Mary Ann Nichols was discovered at about 3:40 a.m. on Friday 31 August 1888 in Buck's Row (now Durward Street), Whitechapel.

Nichols had last been seen alive approximately one hour before the discovery of her body by a Mrs Emily Holland, with whom she had previously shared a bed at a common lodging-house in Thrawl Street, Spitalfields.

Her throat was severed by two deep cuts, one of which completely severed all the tissue down to the vertebrae.

Her vagina had been stabbed twice, and the lower part of her abdomen was partly ripped open by a deep, jagged wound, causing her bowels to protrude.

Several other incisions inflicted to both sides of her abdomen had also been caused by the same knife; each of these wounds had been inflicted in a downward thrusting manner.

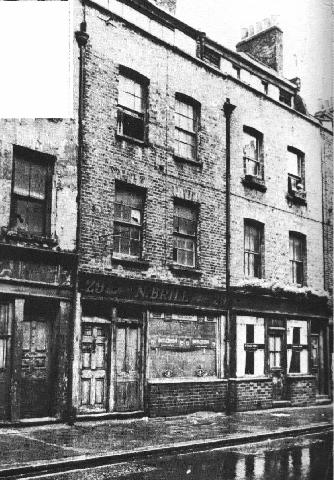

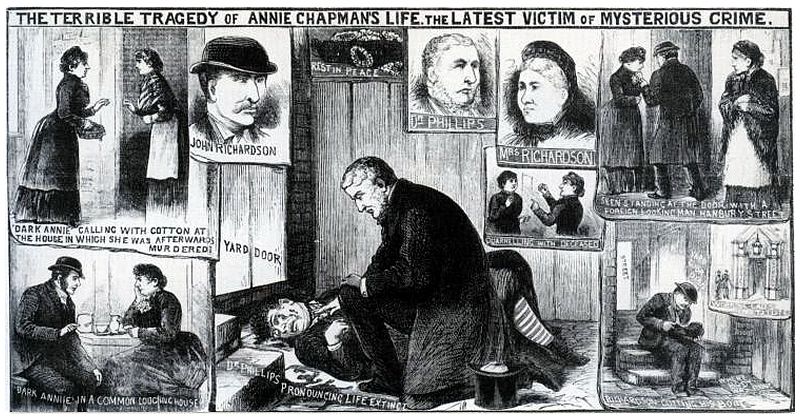

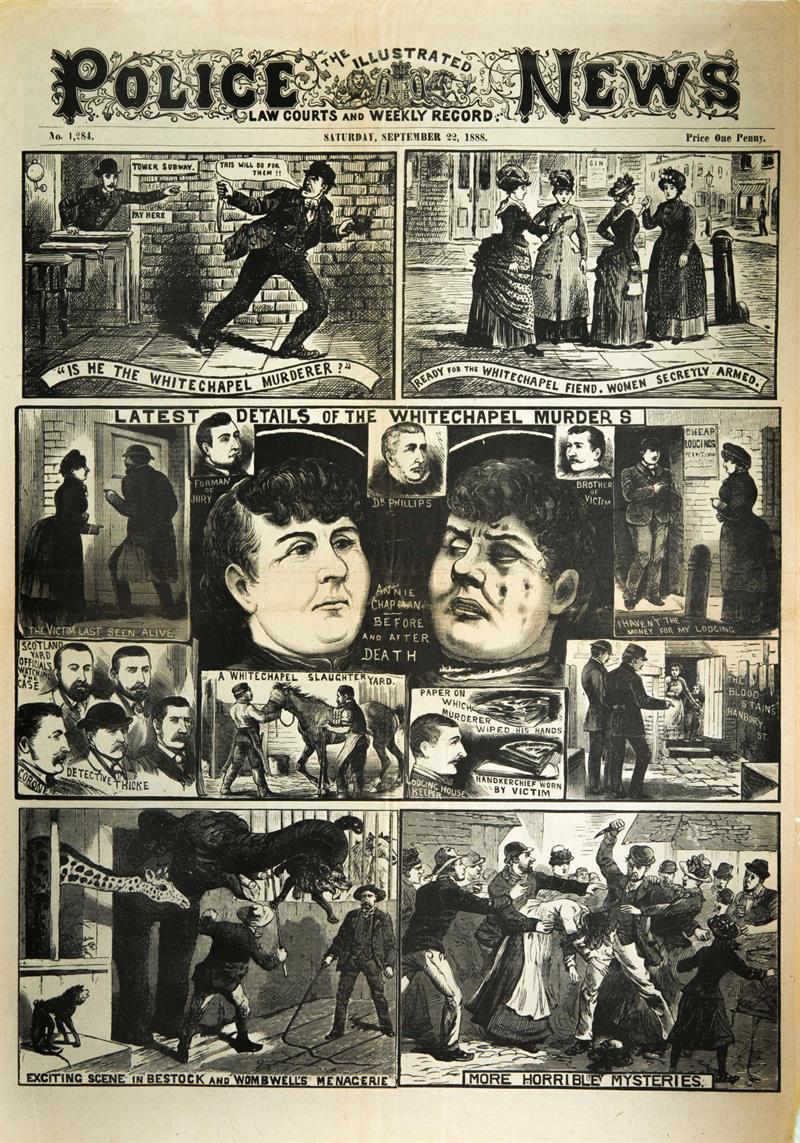

One week later, on Saturday 8 September 1888, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered at approximately 6 a.m. near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields.

As in the case of Mary Ann Nichols, the throat was severed by two deep cuts. Her abdomen had been cut entirely open, with a section of the flesh from her stomach being placed upon her left shoulder and another section

of skin and flesh—plus her small intestines—being removed and placed above her right shoulder.

Chapman's autopsy also revealed that her uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina had been removed.

At the inquest into Chapman's murder, Elizabeth Long described having seen Chapman standing outside 29 Hanbury Street at about 5:30 a.m. in the company of a dark-haired man wearing a brown deer-stalker hat and dark overcoat

and of a "shabby-genteel" appearance. According to this eyewitness, the man had asked Chapman the question, "Will you?" to which Chapman had replied, "Yes."

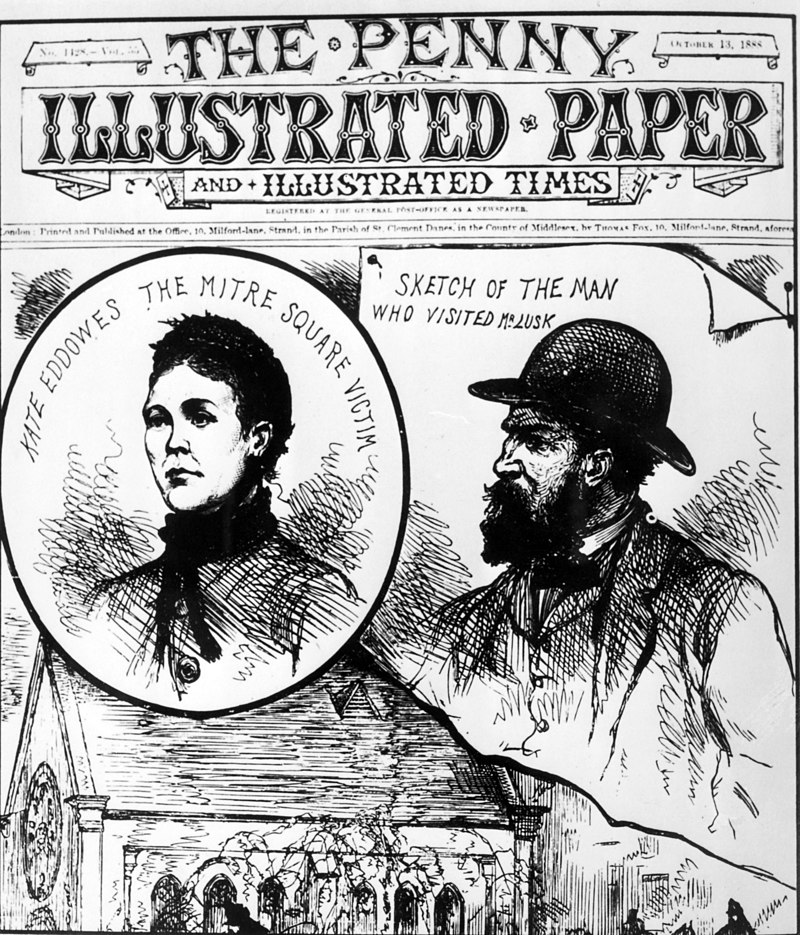

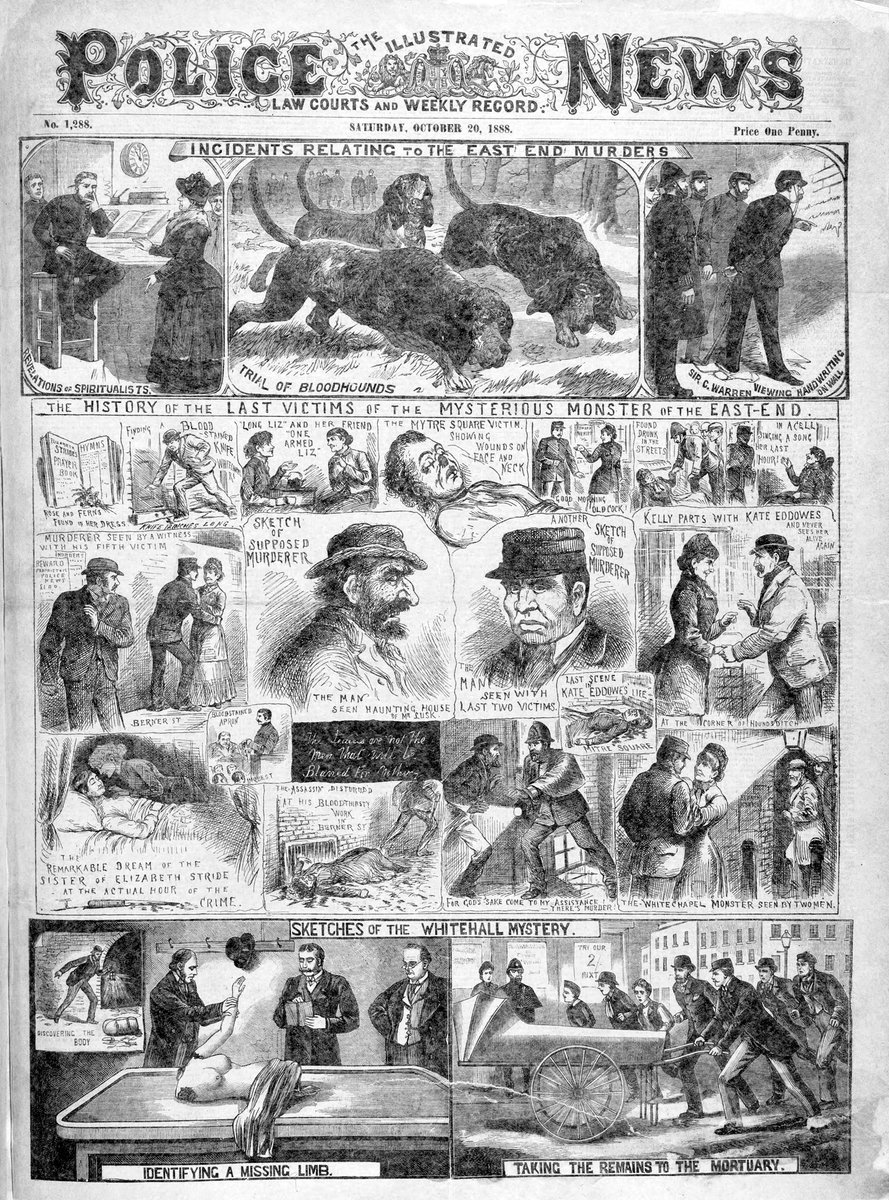

Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were both killed in the early morning hours of Sunday 30 September 1888.

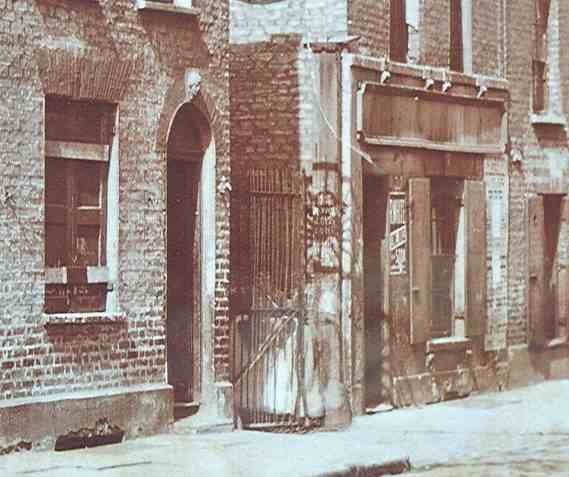

Stride's body was discovered at approximately 1 a.m. in Dutfield's Yard, off Berner Street (now Henriques Street) in Whitechapel

The cause of death was a single clear-cut incision, measuring six inches across her neck which had severed her left carotid artery and her trachea before terminating beneath her right jaw.

The absence of any further mutilations to her body has led to uncertainty as to whether Stride's murder was committed by the Ripper, or whether he was interrupted during the attack

Several witnesses later informed police they had seen Stride in the company of a man in or close to Berner Street on the evening of 29 September and in the early hours of 30 September

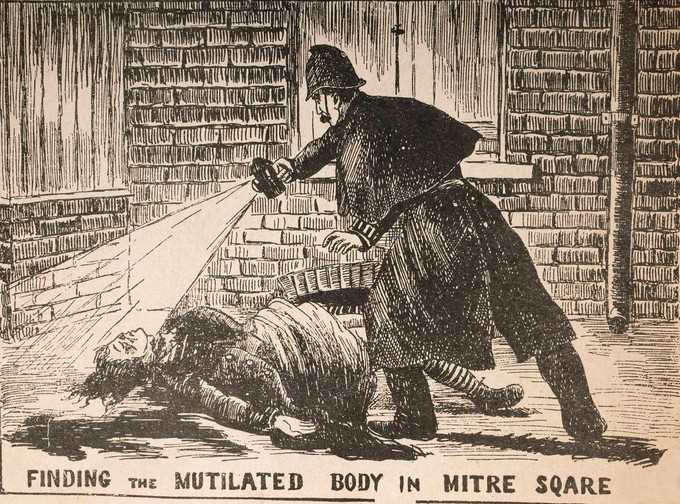

Eddowes's body was found in Mitre Square in the City of London, three-quarters of an hour after the discovery of the body of Elizabeth Stride.

Her throat was severed and her abdomen ripped open by a long, deep and jagged wound before her intestines had been placed over her right shoulder.

The left kidney and the major part of the uterus had been removed, and her face had been disfigured, with her nose severed, her cheek slashed, and cuts measuring a quarter of an inch and a half an inch respectively vertically incised through each of her eyelids.

A triangular incision—the apex of which pointed towards Eddowes's eye—had also been carved upon each of her cheeks, and a section of the auricle and lobe of her right ear was later recovered from her clothing.

A local cigarette salesman named Joseph Lawende had passed through the square with two friends shortly before the murder, and he described seeing a fair-haired man of shabby appearance with a woman who may have been Eddowes.

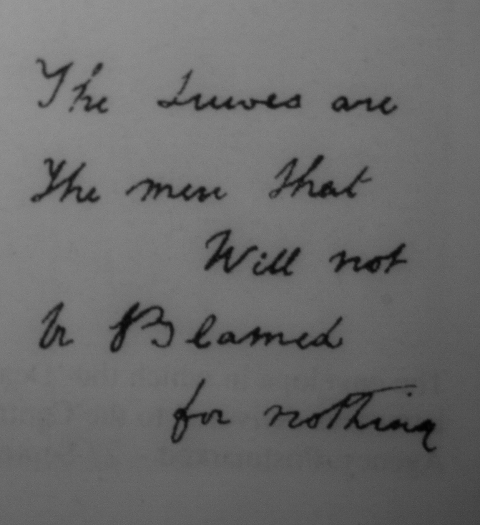

A section of Eddowes's bloodied apron was found at the entrance to a tenement in Goulston Street, Whitechapel, at 2:55 a.m.

A chalk inscription upon the wall directly above this piece of apron read: "The Juwes are The men That Will not be Blamed for nothing." This graffito became known as the Goulston Street graffito.

The message appeared to imply that a Jew or Jews in general were responsible for the series of murders, but it is unclear whether the graffito was written by the murderer on dropping the section of apron,

or was merely incidental and nothing to do with the case.Police Commissioner Charles Warren feared that the graffito might spark anti-semitic riots and ordered the writing washed away before dawn.

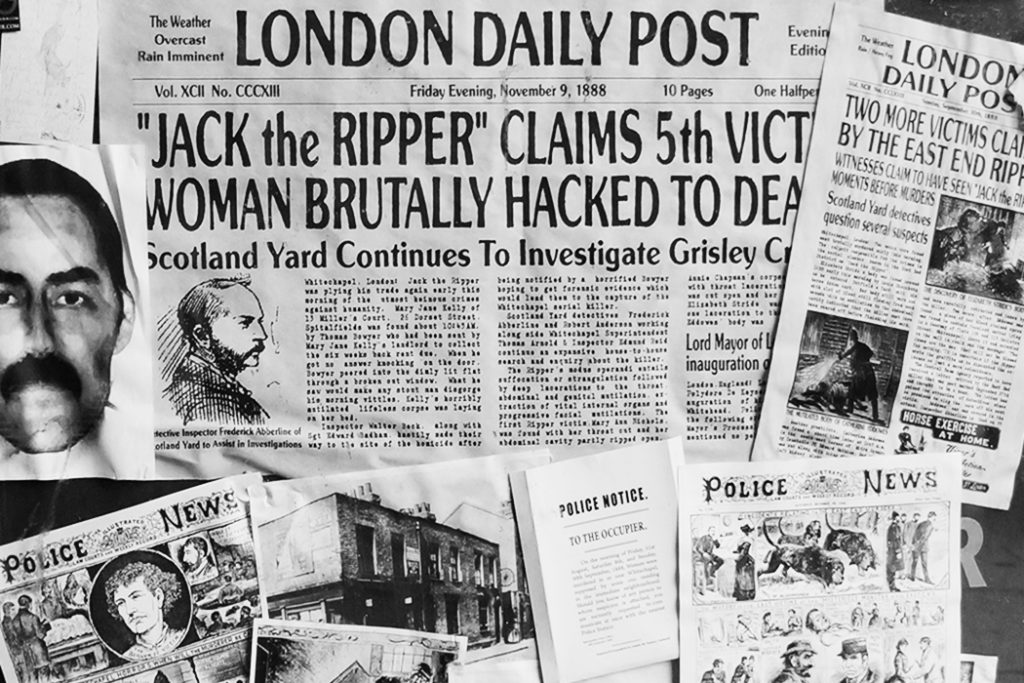

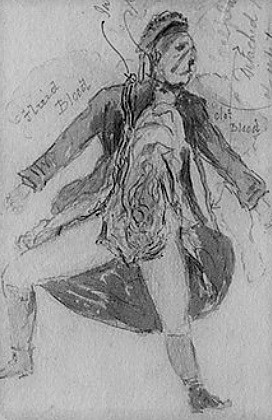

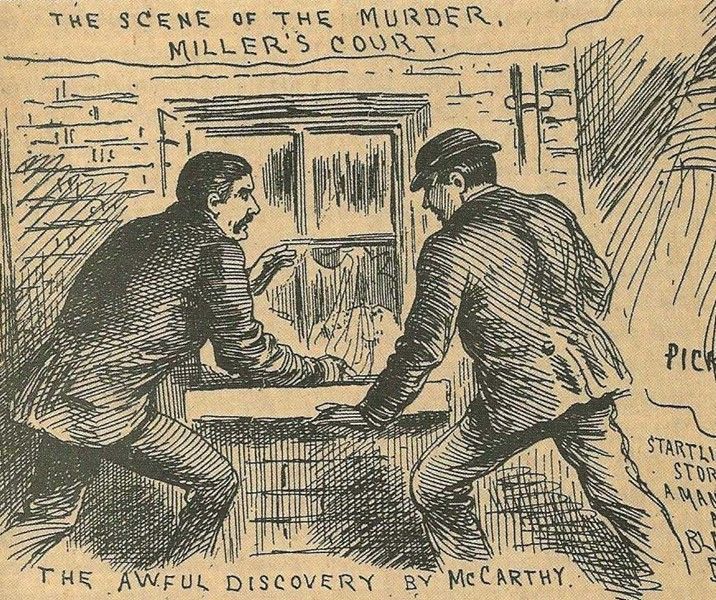

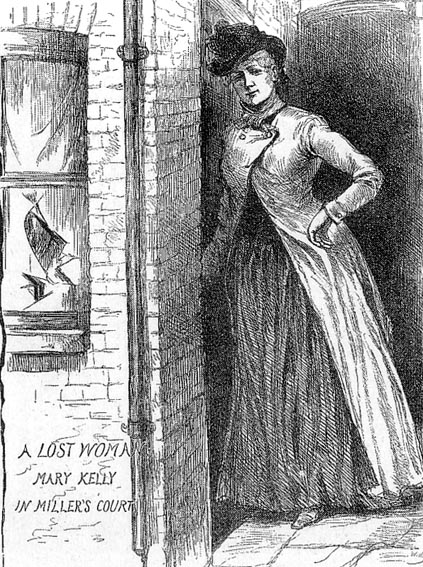

The extensively mutilated and disembowelled body of Mary Jane Kelly was discovered lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, at 10:45 a.m. on Friday 9 November 1888.

Her face had been "hacked beyond all recognition", with her throat severed down to the spine, and the abdomen almost emptied of its organs. Her uterus, kidneys and one breast had been placed beneath her head,

and other viscera from her body placed beside her foot, about the bed and sections of her abdomen and thighs upon a bedside table. The heart was missing from the crime scene.

Each of the canonical five murders was perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after.

The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted.

Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina were taken; Eddowes had her uterus and left kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was extensively eviscerated,

with her face "gashed in all directions" and the tissue of her neck being severed to the bone, although the heart was the sole body organ missing from this crime scene.

Historically, the belief these five canonical murders were committed by the same perpetrator is derived from contemporary documents which link them together to the exclusion of others.

Mary Jane Kelly is generally considered to be the Ripper's final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit's death, imprisonment, institutionalisation, or emigration.

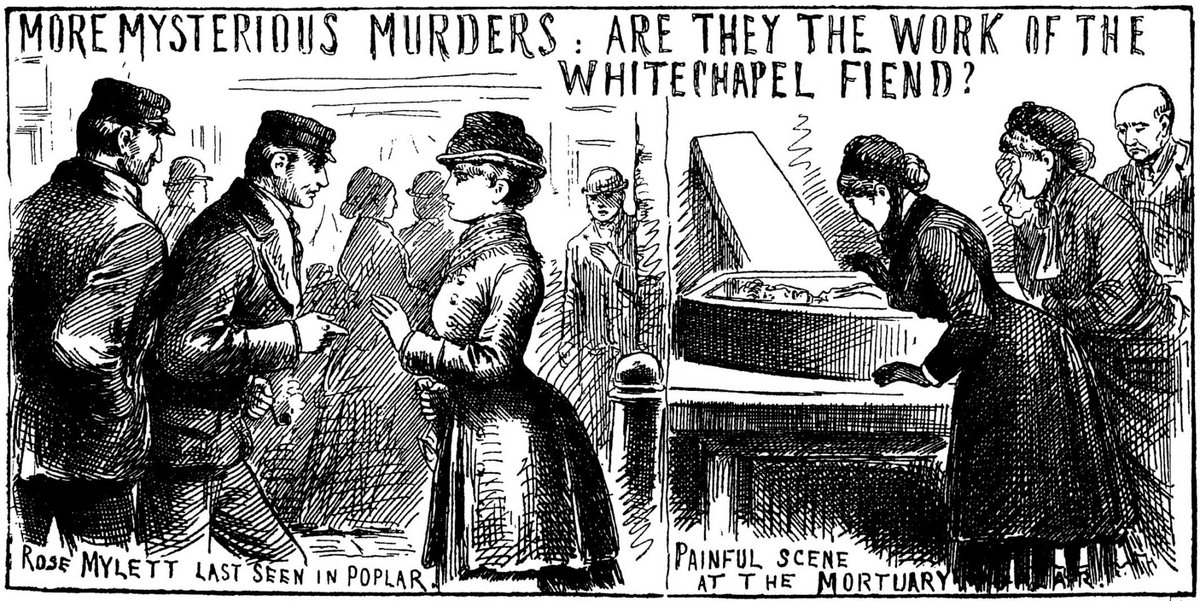

The Whitechapel murders file details another four murders which occurred after the canonical five: those of Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, the Pinchin Street torso, and Frances Coles.

The strangled body of 26-year-old Rose Mylett was found in Clarke's Yard, High Street, Poplar on 20 December 1888.

There was no sign of a struggle, and the police believed that she had either accidentally hanged herself with her collar while in a drunken stupor or committed suicide.

However, faint markings left by a cord on one side of her neck suggested Mylett had been strangled. At the inquest into Mylett's death, the jury returned a verdict of murder

Alice McKenzie was murdered shortly after midnight on 17 July 1889 in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. She had suffered two stab wounds to her neck, and her left carotid artery had been severed.

Several minor bruises and cuts were found on her body, which also bore a seven-inch long superficial wound extending between beneath her left breast and her navel.

One of the examining pathologists, Thomas Bond, believed this to be a Ripper murder, though his colleague George Bagster Phillips, who had examined the bodies of three previous victims, disagreed.

Opinions between writers are also divided between those who suspect McKenzie's murderer copied the modus operandi of Jack the Ripper to deflect suspicion from himself, and those who ascribe this murder to Jack the Ripper.

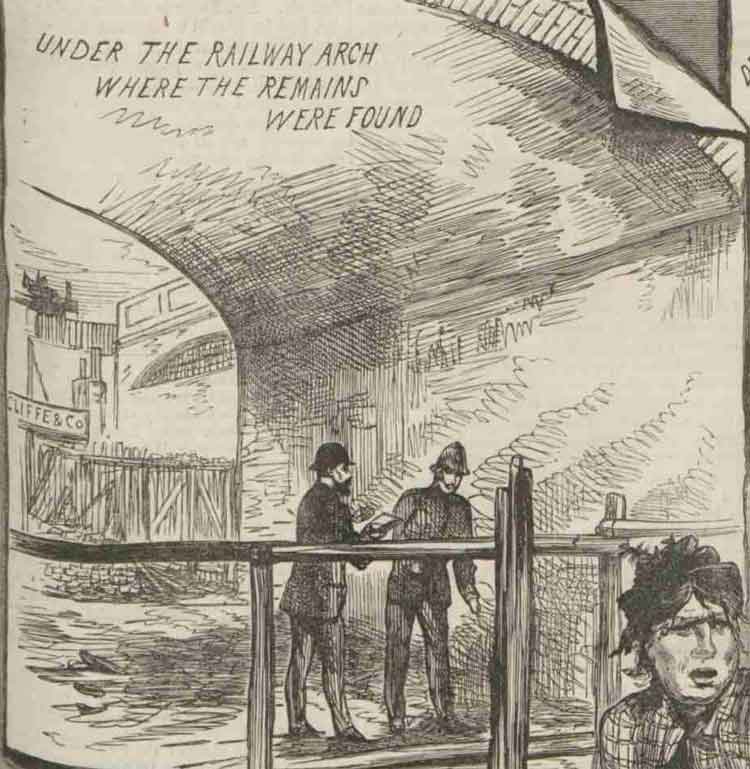

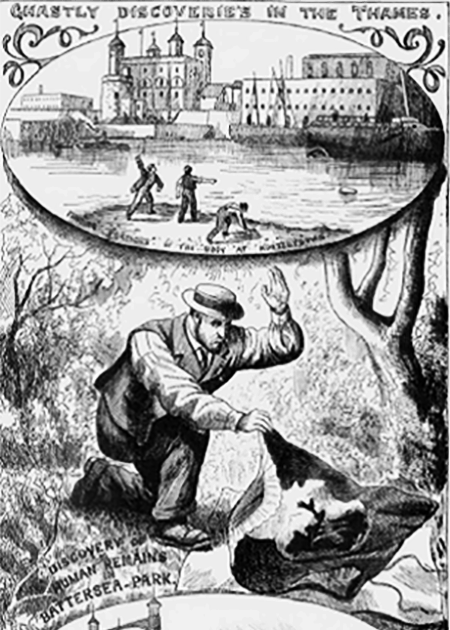

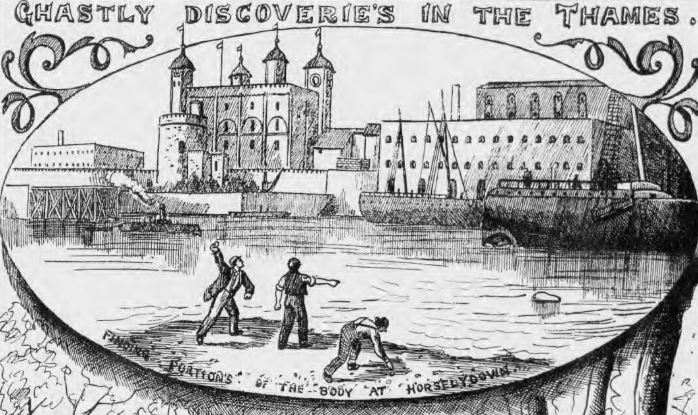

"The Pinchin Street torso" was a decomposing headless and legless torso of an unidentified woman aged between 30 and 40 discovered beneath a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel, on 10 September 1889.

Bruising about the victim's back, hip, and arm indicated the decedent had been extensively beaten shortly before her death. The victim's abdomen was also extensively mutilated, although her genitals had not been wounded.

She appeared to have been killed approximately one day prior to the discovery of her torso. The dismembered sections of the body are believed to have been transported to the railway arch, hidden under an old chemise.

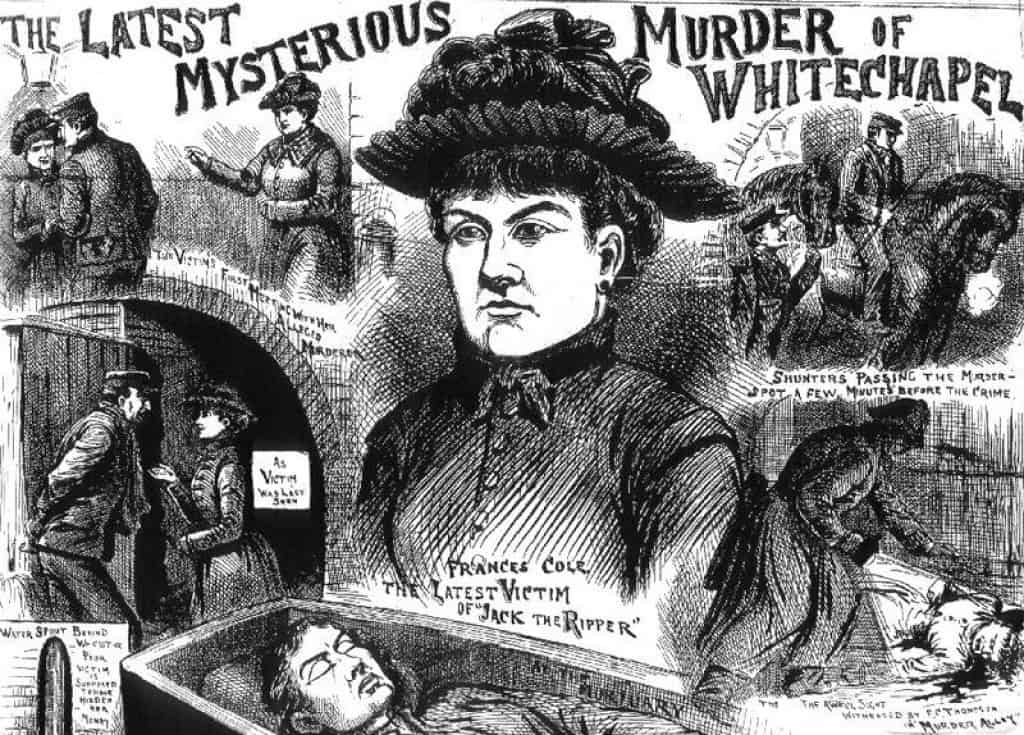

At 2:15 a.m. on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 25-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel.

Her throat had been deeply cut but her body was not mutilated, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant. Coles was still alive, although she died before medical help could arrive.

A 53-year-old stoker, James Thomas Sadler, had earlier been seen drinking with Coles, and the two are known to have argued approximately three hours before her death.

Sadler was arrested by the police and charged with her murder. He was briefly thought to be the Ripper, but was later discharged from court for lack of evidence on 3 March 1891.

In addition to the eleven Whitechapel murders, commentators have linked other attacks to the Ripper

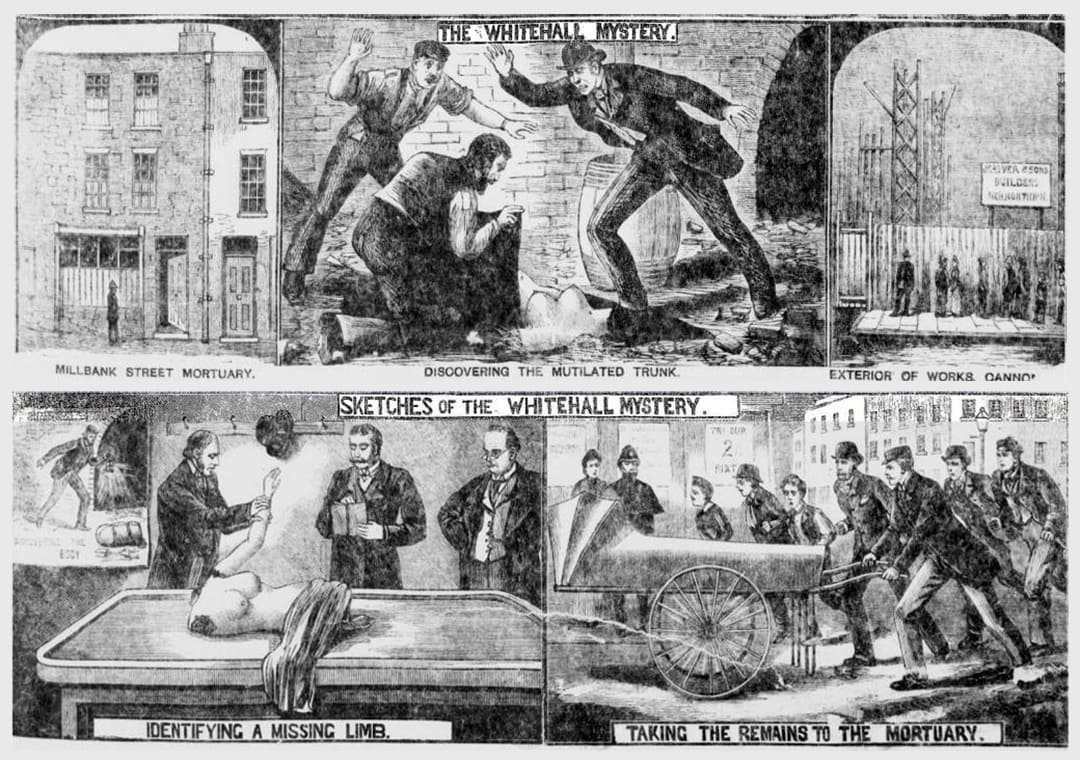

"The Whitehall Mystery" was a term coined for the discovery of a headless torso of a woman on 2 October 1888 in the basement of the new Metropolitan Police headquarters being built in Whitehall.

An arm and shoulder belonging to the body were previously discovered floating in the River Thames near Pimlico on 11 September, and the left leg was subsequently discovered buried near where the torso was found on 17 October.

The other limbs and head were never recovered and the body was never identified. The mutilations were similar to those in the Pinchin Street torso case, where the legs and head were severed but not the arms.

Both the Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders called the "Thames Mysteries", committed by a single serial killer dubbed the "Torso killer".

It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area. The modus operandi of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two.

Elizabeth Jackson was a prostitute whose various body parts were collected from the river Thames over a three-week period in June 1889. She may have been another victim of the "Torso killer".

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in the Blitz. The surviving Metropolitan Police files allow a detailed view of investigative procedures in the Victorian era.

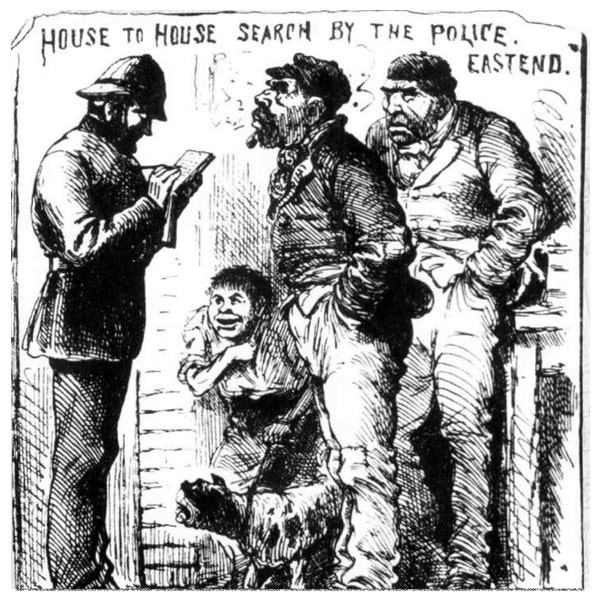

A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced, and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry.

More than 2,000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.

Following the murders of Stride and Eddowes, the Commissioner of the City Police, Sir James Fraser, offered a reward of £500 for the arrest of the Ripper.

The investigation was initially conducted by the Metropolitan Police Whitechapel (H) Division Criminal Investigation Department (CID) headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid.

After the murder of Nichols, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard to assist.

The City of London Police were involved under Detective Inspector James McWilliam after the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the City of London.

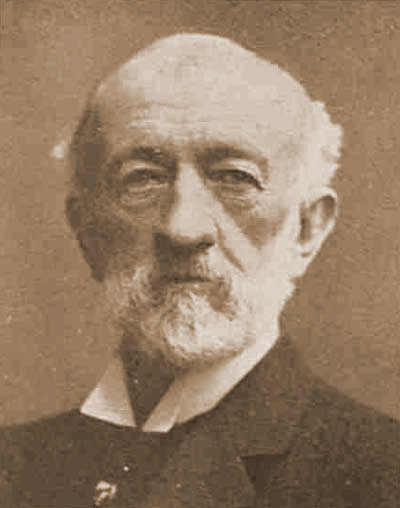

The overall direction of the murder enquiries was hampered by the fact that the newly appointed head of the CID Robert Anderson was on leave in Switzerland between 7 September and 6 October,

during the time when Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes were killed. This prompted Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to appoint Chief Inspector Donald Swanson to coordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard.

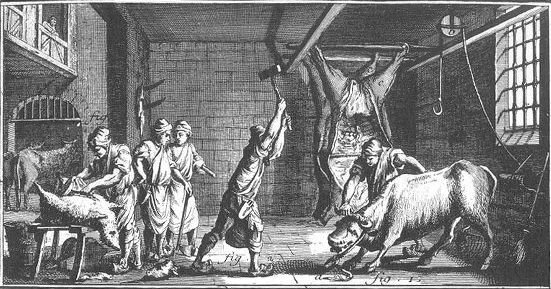

Butchers, slaughterers, surgeons, and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations.

A surviving note from Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City Police, indicates that the alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry

Some contemporary figures, including Queen Victoria, thought the pattern of the murders indicated that the culprit was a butcher or cattle drover on one of the cattle boats that plied between London and mainland Europe.

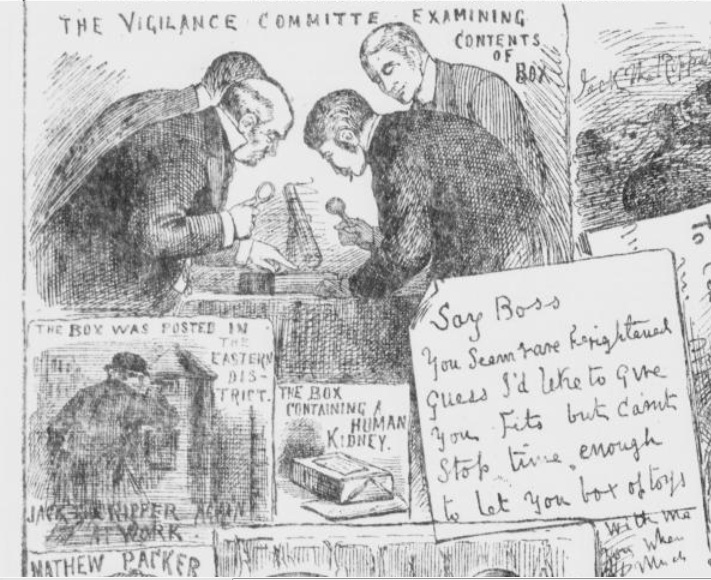

In September 1888, a group of volunteer citizens in London's East End formed the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee.

They patrolled the streets looking for suspicious characters, partly because of dissatisfaction with the failure of police to apprehend the perpetrator, and also because some members were concerned that the murders were affecting businesses in the area.

The Committee petitioned the government to raise a reward for information leading to the arrest of the killer, offered their own reward of £50 for information leading to his capture, and hired private detectives to question witnesses independently

At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer's surgical skill and knowledge.

The opinion offered by Bond on the character of the "Whitechapel murderer" is the earliest surviving offender profile.

Bond was strongly opposed to the idea that the murderer possessed any kind of scientific or anatomical knowledge, or even "the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer".

In his opinion, the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania", with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating "satyriasis".

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally.

Others have thought that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area

Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich.

There are many, varied theories about the identity and profession of Jack the Ripper, but authorities are not agreed upon any of them, and the number of named suspects reaches over one hundred.

Over the course of the Whitechapel murders, the police, newspapers, and other individuals received hundreds of letters regarding the case.

Some letters were well-intentioned offers of advice as to how to catch the killer, but the vast majority were either hoaxes or generally useless.

Hundreds of letters claimed to have been written by the killer himself, and three of these in particular are prominent: the "Dear Boss" letter, the "Saucy Jacky" postcard and the "From Hell" letter.

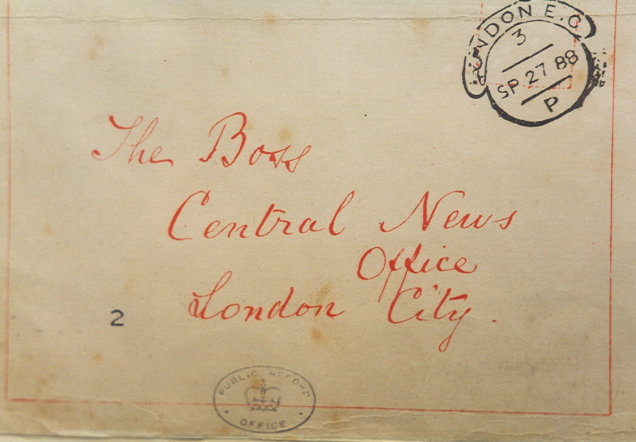

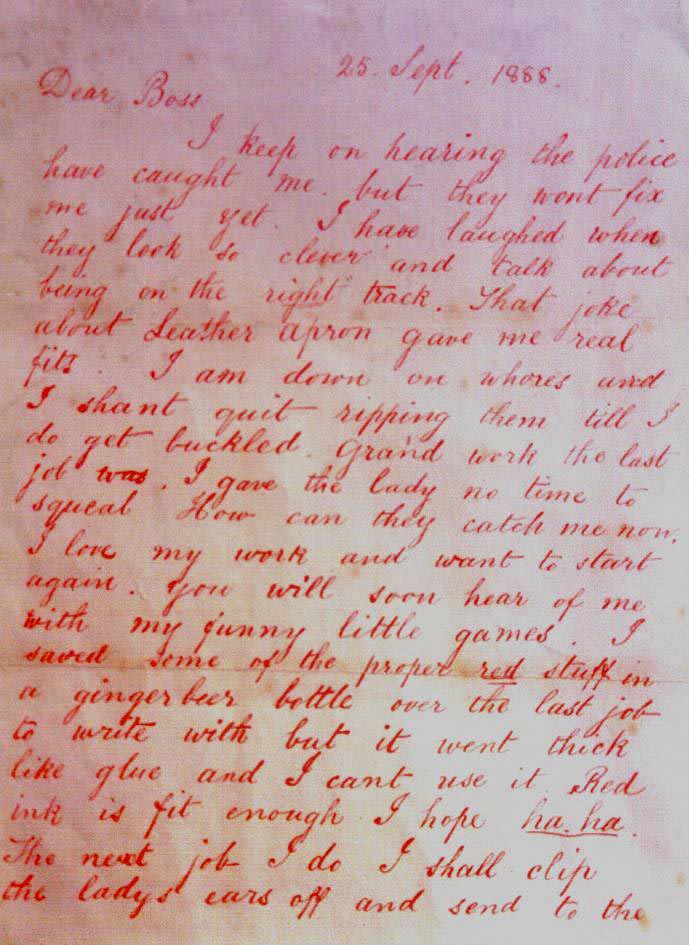

The "Dear Boss" letter, dated 25 September and postmarked 27 September 1888, was received that day by the Central News Agency, and was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September.

Initially, it was considered a hoax, but when Eddowes was found three days after the letter's postmark with a section of one ear obliquely cut from her body, the promise of the author to "clip the ladys (sic) ears off" gained attention.

Eddowes's ear appears to have been nicked by the killer incidentally during his attack, and the letter writer's threat to send the ears to the police was never carried out.

The name "Jack the Ripper" was first used in this letter by the signatory and gained worldwide notoriety after its publication. Most of the letters that followed copied this letter's tone.

Some sources claim that another letter dated 17 September 1888 was the first to use the name "Jack the Ripper", but most experts believe that this was a fake inserted into police records in the 20th century.

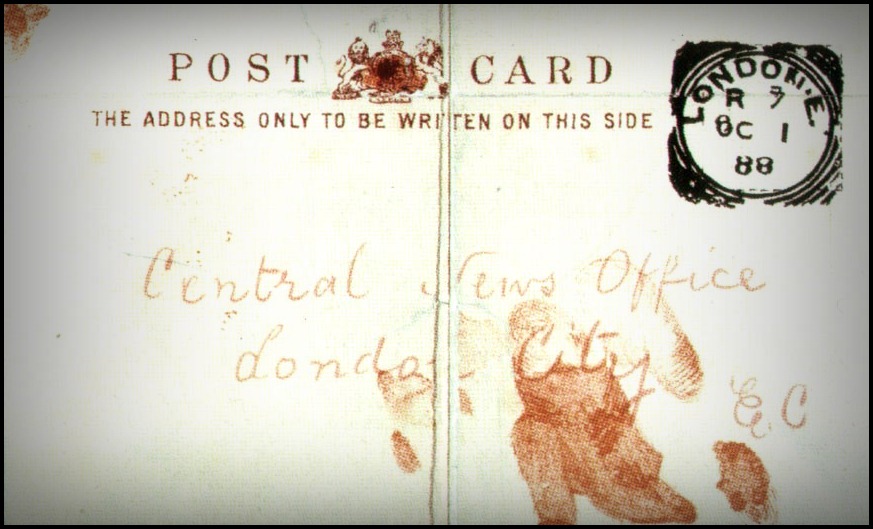

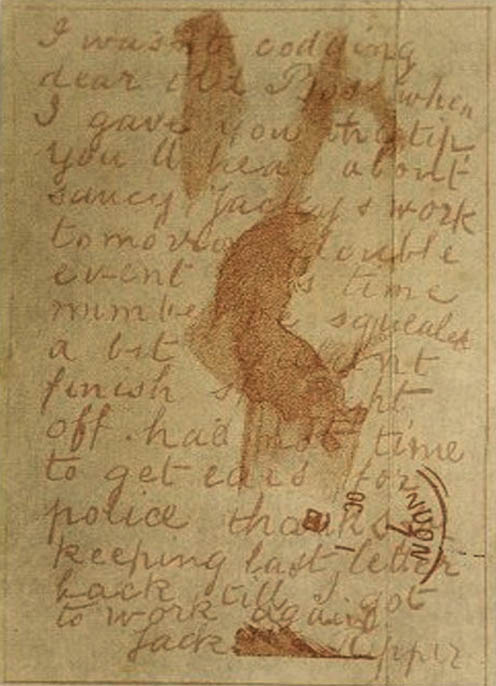

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1 October 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September,

which the author refers to by writing "double event this time". It has been argued that the postcard was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would hold such knowledge of the crime.

However, it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings occurred, long after details of the murders were known and publicised by journalists, and had become general community gossip by the residents of Whitechapel.

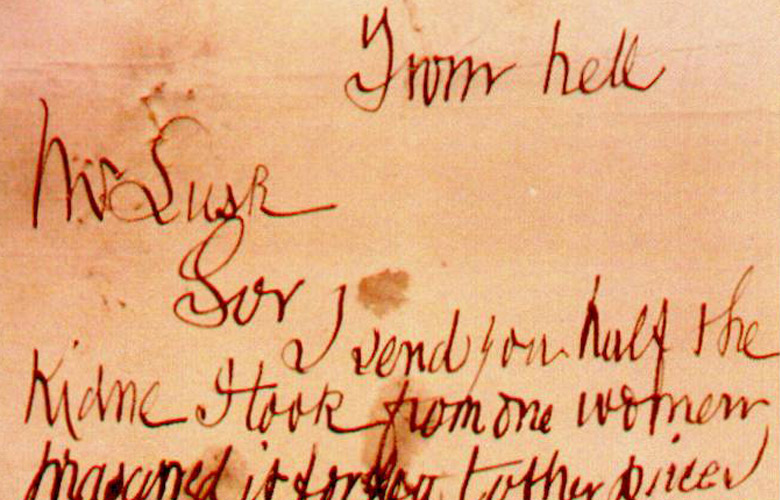

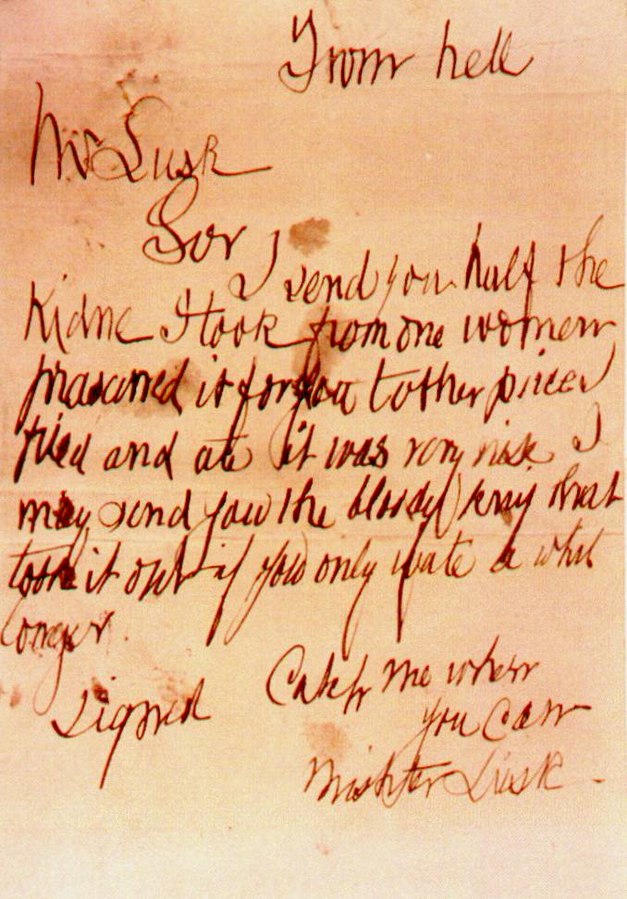

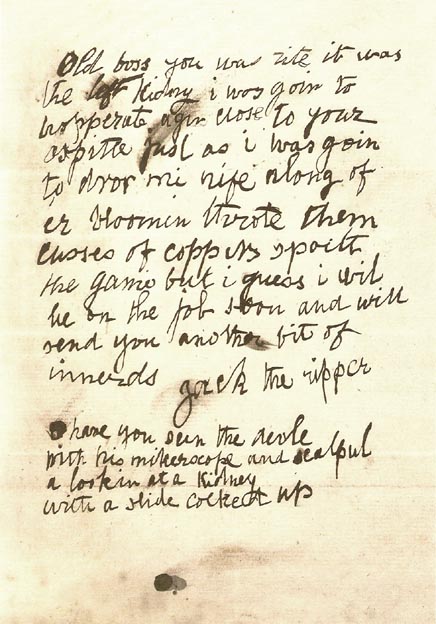

The "From Hell" letter was received by George Lusk, leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on 16 October 1888. The handwriting and style is unlike that of the "Dear Boss" letter and "Saucy Jacky" postcard.

The letter came with a small box in which Lusk discovered half of a human kidney, preserved in "spirits of wine" (ethanol). Eddowes's left kidney had been removed by the killer. The writer claimed that he "fried and ate" the missing kidney half.

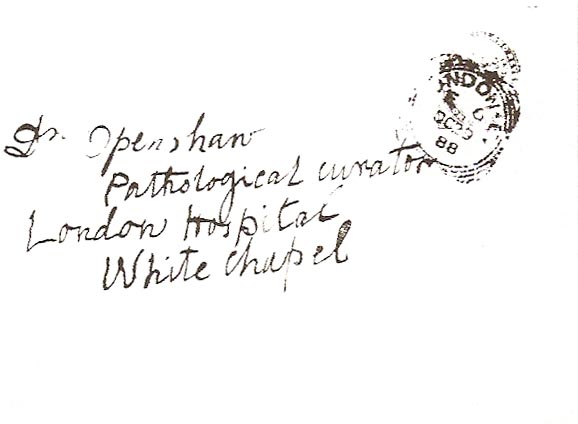

The kidney was examined by Dr Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital, who determined that it was human and from the left side, but he could not determine any other biological characteristics. Openshaw subsequently also received a letter signed "Jack the Ripper".

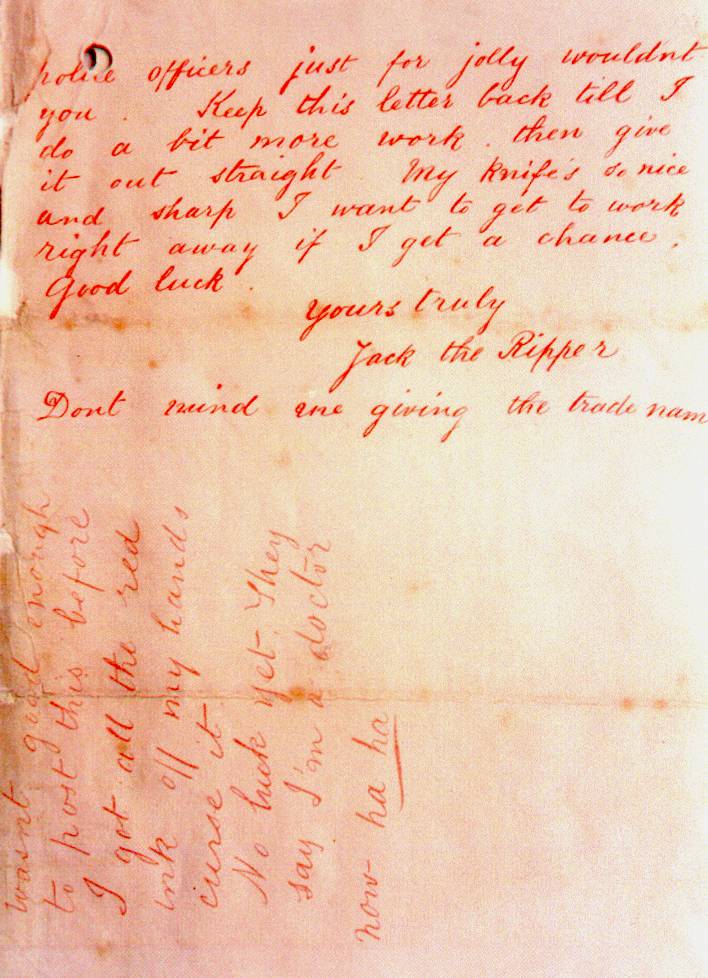

Scotland Yard published facsimiles of the "Dear Boss" letter and the postcard on 3 October, in the ultimately vain hope that a member of the public would recognise the handwriting.

Police officials later claimed to have identified a specific journalist as the author of both the "Dear Boss" letter and the postcard.

The journalist was identified as Tom Bullen in a letter from Chief Inspector John Littlechild to George R. Sims dated 23 September 1913.

A journalist named Fred Best reportedly confessed in 1931 that he and a colleague at The Star had written the letters signed "Jack the Ripper" to heighten interest in the murders and "keep the business alive"

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in the treatment of crime by journalists. Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer, but his case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy.

Tax reforms in the 1850s had enabled the publication of inexpensive newspapers with a wider circulation.

These mushroomed in the later Victorian era to include mass-circulation newspapers costing as little as a halfpenny, along with popular magazines such as The Illustrated Police News which made the Ripper the beneficiary of previously unparalleled publicity.

Consequently, at the height of the investigation, over one million copies of newspapers with extensive coverage devoted to the Whitechapel murders were sold each day.

However, many of the articles were sensationalistic and speculative, and false information was regularly printed as fact.

In addition, several articles speculating as to the identity of the Ripper alluded to local xenophobic rumours that the perpetrator was either Jewish or foreign.

The nature of the Ripper murders and the impoverished lifestyle of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, insanitary slums.

In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by various guided tours of the murder sites and other locations pertaining to the case.

🔪 The End 🔪

Thank you for reading until the end. I hope this thread has been not too harsh to read... all the threads that I'll share in October will be about mysteries, ghost stories, murders and spooky stuff in general 🕸️👻

Thank you for reading until the end. I hope this thread has been not too harsh to read... all the threads that I'll share in October will be about mysteries, ghost stories, murders and spooky stuff in general 🕸️👻

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh