I'll be making a tabulation of Neandertal specimens that have yielded molecular (DNA, proteomic) sequence information. I know there are more than 30 but I'd like to get an actual count and link photos where possible. This will take a while, and I'll add to this thread as I go.

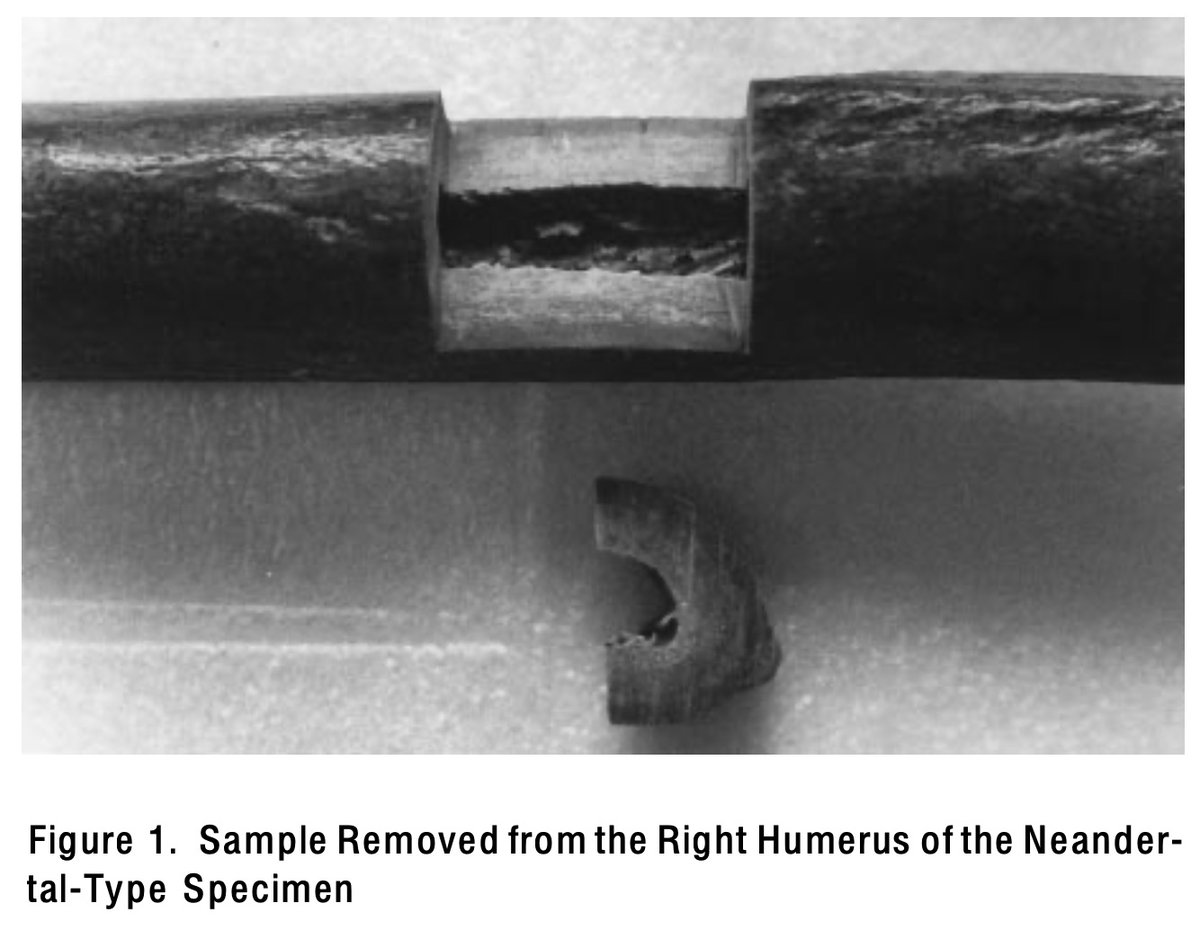

The first mtDNA fragments published from any Neandertal specimen were from the humerus of the Neandertal 1 skeleton, from the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte near Mettmann, Germany. The partial skeleton was recovered in 1856. Sequencing by Matthias Krings et al. doi.org/10.1016/S0092-…

Ralf Schmitz and Jürgen Thissen relocated sediments from the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte, excavating in 1997 and 2000. They found new bone fragments that refit the Neandertal 1 skeleton and a humerus fragment (NN 1) that must represent a second individual. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1…

Schmitz et al. 2002 reported the partial mtDNA sequence of the NN 1 humerus fragment, distinct from the Neandertal 1 mtDNA sequence. They examined another fragment, NN 4, which did not yield DNA. Pictured here is NN 1 with refitted fragments NN 2, NN 3 and NN 47.

The third and fourth Neandertals on my list are together a strange case. In 2000, Michael Scholz and coworkers reported that they carried out DNA-DNA hybridization from bone extracts from fossil material, including two "Neandertals". doi.org/10.1086/302949

Other specialists in ancient DNA analysis immediately challenged these results, arguing that basic standards had not been met and results were probably driven by contamination, not endogenous Neandertal DNA. No sequence information was generated. doi.org/10.1086/316948

The first specimen sampled in this study was a parietal bone from Warendorf-Neuwarendorf, Germany. This was attributed to Neandertals by Scholz et al. 1999 and Czarnetzki and Trellisó-Carreño 1999. Little has been published on this specimen.

The second is a clavicle that Scholz et al claimed was from Krapina. They provided this information (and no photo): "Krapina Fe. 1.si/213 Geological and Paleontological Museum, Zagreb, Croatia". There were two weird things about this...

First, the curator of the museum in Zagreb at the time couldn't substantiate that this bone was actually from Krapina. The paper cited no permits, no permissions. The bone seemed to come out of nowhere.

Second, the number provided, "Krapina Fe.1.si/213" corresponds to a femur fragment, not a clavicle, and it's still in Zagreb. This wouldn't be the last time that a DNA paper on Neandertals had some really fishy provenence, but it may be the most egregious.

Was this actually a Neandertal? With a site that was dug 100 years before this paper, there was a chance that bone had been distributed to Tübingen early in the 20th century and remained in that collection. But I still don't know.

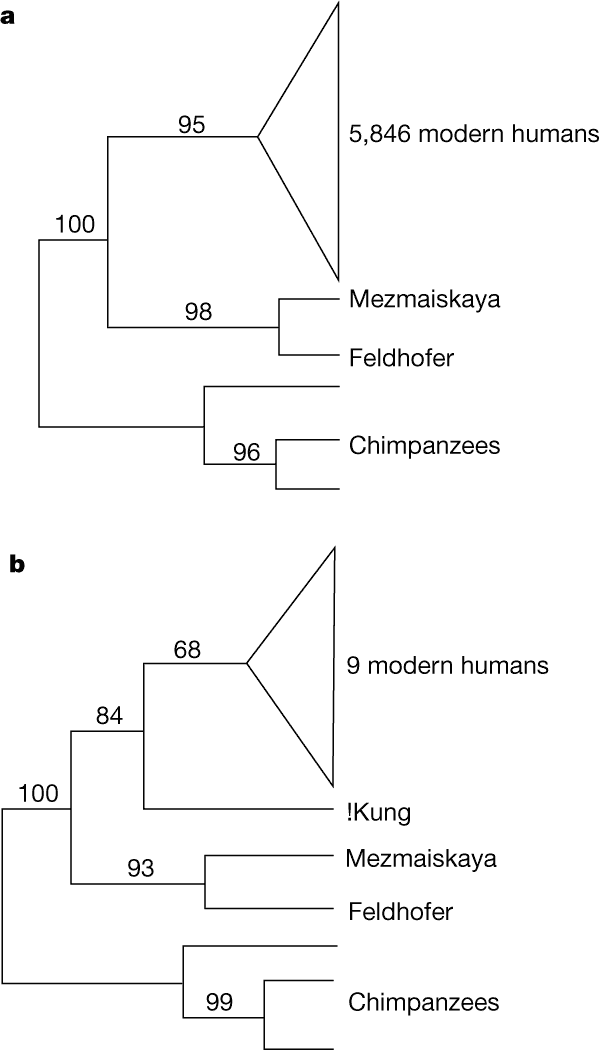

The second partial mtDNA sequence from a Neandertal to be published was from the rib of an infant skeleton from Mezmaiskaya Cave, Russia. Work done by Ovchinnikov et al. 2000 doi.org/10.1038/350066…

The infant skeleton was the first individual to be uncovered at the site, described by Golovanova et al. 1999. Later this specimen would be numbered as Mezmaiskaya 1. doi.org/10.1086/515805

Mezmaiskaya 1 was the target of additional sequencing in several later studies, including the Briggs et al. sequencing of the complete mtDNA doi.org/10.1126/scienc… and partial nuclear genome recovery by Green et al. 2010. doi.org/10.1126/scienc…

Before I leave Mezmaiskaya 1, let me share this wonderful reconstruction of the skeleton done by Marcia Ponce de Leon and coworkers in 2008. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0…

Mezmaiskaya 2 is a second individual, unearthed later from a different, more recent, context at the site. It is reported to include 24 cranial fragments. Briggs et al. 2009 recovered a partial mtDNA sequence from this specimen doi.org/10.1126/scienc…

I haven't been able to find a scientific description or photos of Mezmaiskaya 2. It has been mentioned in the context of dating at the site, including a direct C14 AMS date (uncalibrated 39,700 ± 1,100 14C BP) reported in 2011 by Pinhasi et al. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1…

Next on the list of Neandertals with DNA successes is a specimen from Vindija, Croatia. Vindija is maybe the most important of the Neandertal sites for ancient biomolecules, ranking with Denisova. Most samples come from the G3 layer, between 45 and 50,000 years old.

Krings et al. 2000 doi.org/10.1038/79855 reported a partial mtDNA sequence from Vi-75, one of the G3 Vindija specimens. This is a fragment that Malez and Ullrich 1982 identified as a metatarsal fragment. I cannot find a photo of this third Neandertal to yield DNA data.

A word about photos: Many Neandertal fragments that have generated DNA were targeted for biomolecular investigation because they preserve little anatomical information. Before digital photography and online journal publications, it was rare to publish photos of such fragments.

This practice has changed somewhat in recent years as photography and preparation of photos for publication has become much cheaper and easier. But published catalogs of fossil sites with photos of all specimens are still rare. Archival photos are more common but hard to access.

Krings et al. 2000 reported extracting bone powder and assessing amino acid racemization on 15 Neandertal specimens from Vindija layer G3. From 7 that appeared to have good biomolecular preservation, they selected Vi-75 as the most promising for further investigation.

Small fragments of mtDNA from two additional Vindija fossils were reported by Serre et al. 2004. In that paper, the two fossils were numbered Vi-77 and Vi-80. These numbers, and Vi-75, once inspired some confusion. doi.org/10.1371/journa…

Ahern et al. 2004 provided some useful background on the excavation and numbering system at Vindija. Malez excavated in the 1970s and 1980s. A new numbering system was put into place during the late 1990s. doi.org/10.1016/j.jhev…

Old specimen numbers of the Vi-75, Vi-77 kind were catchalls for area designations. Nondiagnostic hominin bone fragments that may originally have been placed with bulk faunal material started with these numbers. Once identified, they were given numbers in the new system.

Vi-77 was not part of later DNA work, and I haven't found the full Vindija catalog that would tell its new number. Vi-80 was renumbered as Vi 33.16. This fragment of tibia is one of the most important fossil hominins ever discovered.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh