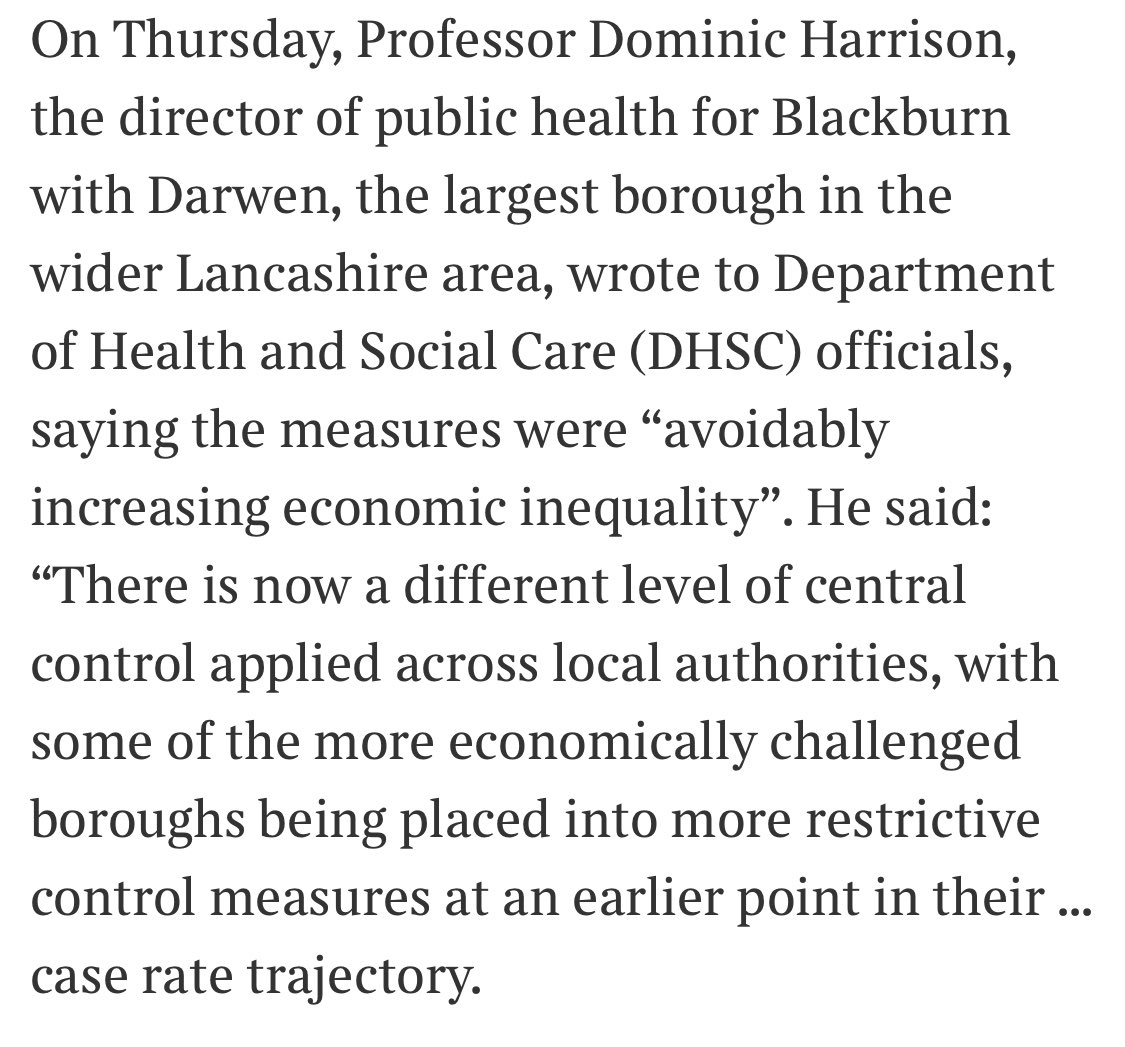

The concern expressed in this article is a direct consequence of the lack of transparency and democratic accountability for the government’s decisions on local lockdowns. thetimes.co.uk/article/no-cor…

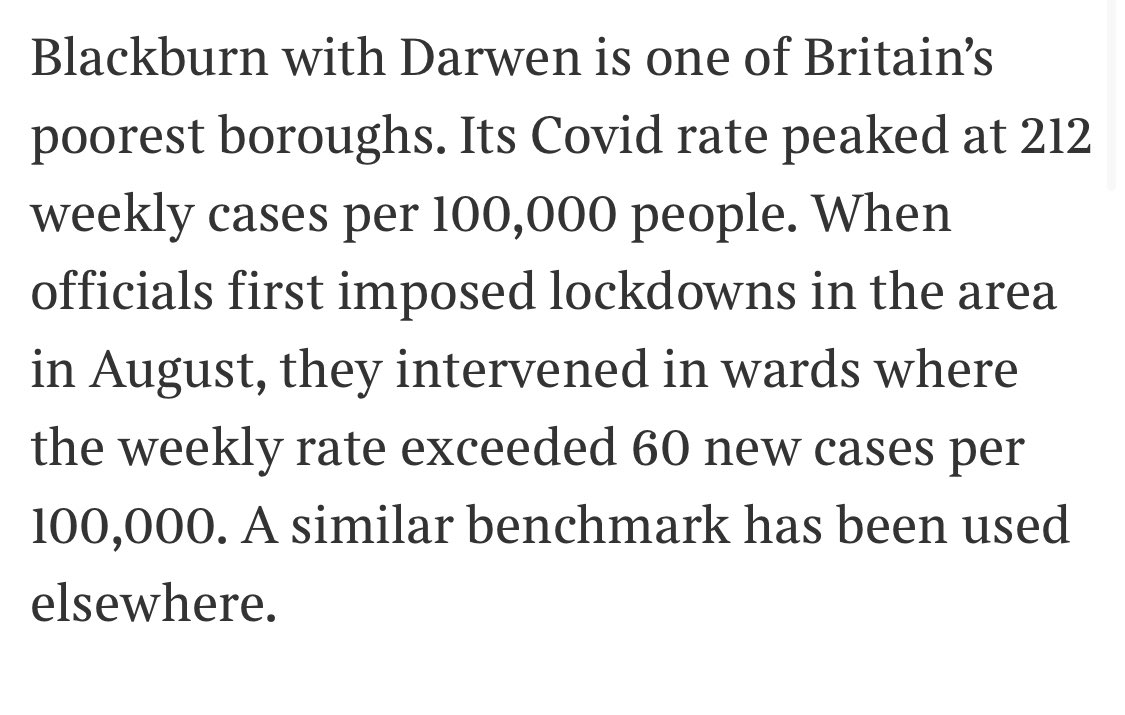

And apparent different treatment of Tory constituencies - by at least the infection rate/100k metric which seems to have been a major factor in decision-making.

The problem is that, in the absence of any transparency about the criteria being used (what other ones are there apart from the rate/100k metric?) you simply can’t tell whether political bias is entering into decision-making.

It’s hard to see anything that is more likely to damage public confidence that the suggestion that Ministers are looking after their own party’s areas.

And without transparency you can’t assess what trade-offs are being made, or what is the impact on existing inequalities of those trade-offs.

The lack of transparency is part and parcel of the lack of effective democratic scrutiny: because such scrutiny would force transparency (as well as, in itself, improving legitimacy and public confidence).

But absent transparency and proper scrutiny, the suggestion of gross political bias, and the suggestion that poorer areas are being hit hardest, will take root. With substantial damage to public confidence - on which the success of these measures - and lives - depend.

That is why there is no tension between proper democratic governance and effectiveness here: on the contrary, the two go hand in hand: proper democratic governance (transparency/scrutiny/accountability) is essential to public confidence and hence to effectiveness.

It’s worth noting that all these points and concerns - including issues about geographical selectiveness and equality) were powerfully raised in July by a @SocLabLaw paper on easing (and re-imposing) the lockdown (to which I contributed). …c-4eeb-be13-51b5736f1b93.filesusr.com/ugd/01ea09_7a8…

Some things have moved on. And we didn’t foresee that gross political bias might be a possible concern. But the basic points remain on the nail.

NB: there are real technical difficulties here, in particular that making the relevant regulations under the draft affirmative procedure (ie only taking effect after a positive vote by both Houses) takes too much time.

But a government that actually welcomed scrutiny, and saw its importance, would have found a way to ensure it (using its majority to make any necessary procedural changes).

Unfortunately, we don’t have such a government.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh