What connects ancient Mesopotamia, Rosetta Stone, your liver, mayonnaise, the last letter of the Greek alphabet, dark chocolate, fake meat and heart disease? The answer is sesame. A thread

Rather than randomly connect multiple facts, this thread will attempt to use why and how questions to rabbit-hole from one fact to another. And try and keep the science at an #ELI5 level.

It turns out that we know that the ancient Akkadian word for sesame was "Ellu", and the Sumerian word for it was “Illu”, both of which are rather surprising because the Tamil word for it is…"Ellu"

The prevailing theory is that the Indus Valley was a trading partner of Sumer and Akkad, and sesame was one of the things that Mesopotamians imported from the Harappans.

Just so we appreciate how old Sumer and Harappa were in the context of what we are talking about, they are older than Emperor Ashoka (2400 years before his rule) than he is to us (2200 years)

Back to sesame, because imports tend to often retain their original names in the language of their geographical origin, it’s surmised that the Harappans likely called sesame ”Ellu”.

Why is this important? Because if the Harappans did indeed call sesame “Ellu”, then it lends further credence to the hypothesis that they probably spoke a Proto-Dravidian language.

Which when you consider in conjunction with the recent population genetics findings (as documented in "Early Indians" by @tjoseph0010) throws a bit of a spanner in the idea of a single, homogenous, Indo-European, Sanskrit-centric civilisation

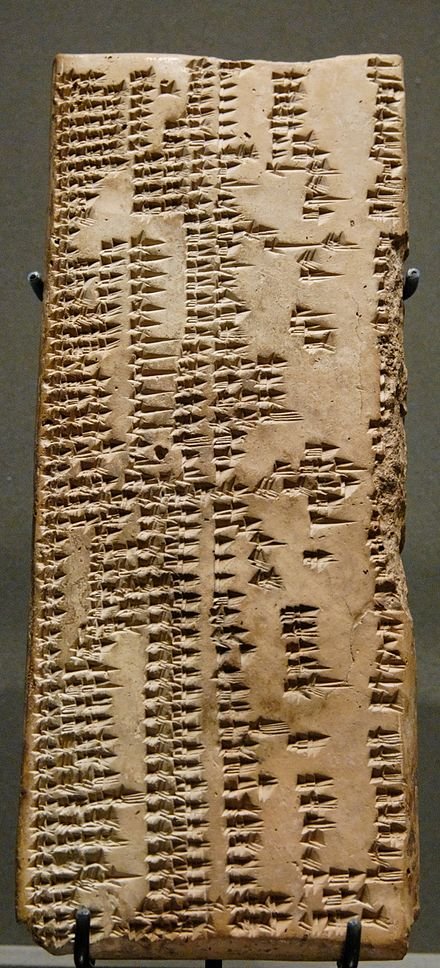

But this thread is about how we find things out rather than the findings themselves, so the question is- how did we come to know that the Mesopotamians called sesame “Ellu”? In other words, how we do look at wedges on a 4500-year-old clay tablet and go “Hey, that’s ellu”.

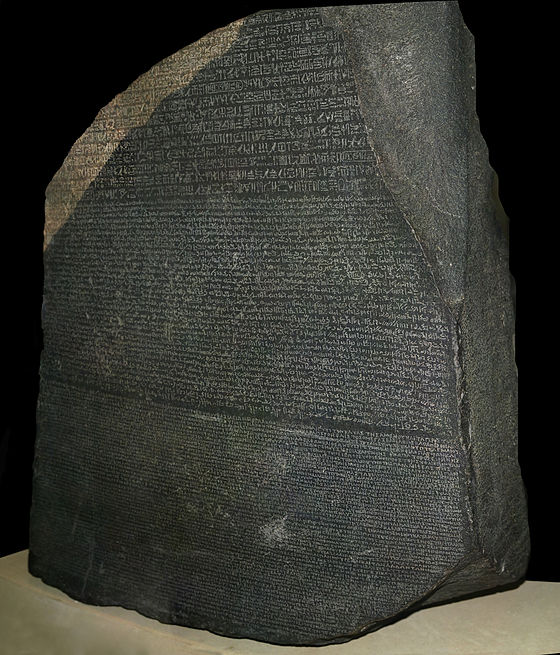

Which brings us to the Behistun inscription. Considered to be the Rosetta Stone for Cuneiform, the script used in ancient Mesopotamia, it was central to deciphering that script

When you consider that the Rosetta stone only had 14 surviving lines of Hieroglyphic text, the Behistun inscription was massive, and that made deciphering cuneiform a lot easier than hieroglyphics

So the next question is - how do you decipher an unreadable script? The Behistun inscription was in 3 languages - Babylonian, Elamite and Old Persian, and rather luckily for us, we had a decent idea of Old Persian

And the inscription had a ton of king & local satrap names, and proper names tend to not change much across languages, so if the inscription spoke of Dharyavaus (Darius) there’s a good chance that every language in that inscription used syllables that read “Dharyavaus”.

So if you can read it in one language, you can learn to recognise it in another, and once you do that, you know the sounds made by the letters that spell those specific proper nouns, and given enough names, you can decipher most letters.

So, next question - how do we know Old Persian? Well, it evolved into Middle Persian & subsequently to the Persian that is spoken in Iran today, and we also have Zoroastrian religious texts written in Avestan, a language very similar to Vedic Sanskrit & Old Persian!

Deciphering ancient languages is super complicated, and I’m really oversimplifying here. We know how to read and speak living languages, so we make intelligent guesses what older versions of those languages sounded like

So once the Persian could be read, it took a while, but the other languages on the inscription, Elamite & Babylonian were also deciphered, and thus the cuneiform script used to write them could now be read.

It’s fascinating when you consider that Cuneiform was used for 4000 years, more than any other script we know in human history! And it’s been extinct for 2000 years!

So, ancient Egyptian and Cuneiform were deciphered thanks to the Rosetta Stone and the Behistun inscription while we do not have a similar multi-lingual inscription with the Indus script, which is one of the reasons it remains undeciphered till date.

So back to the sesame, while we surmise that "Ellu" was a word foreign to Mesopotamia simply because sesame was not native to that part of the world, guess where is Sesame native to? The Indian subcontinent.

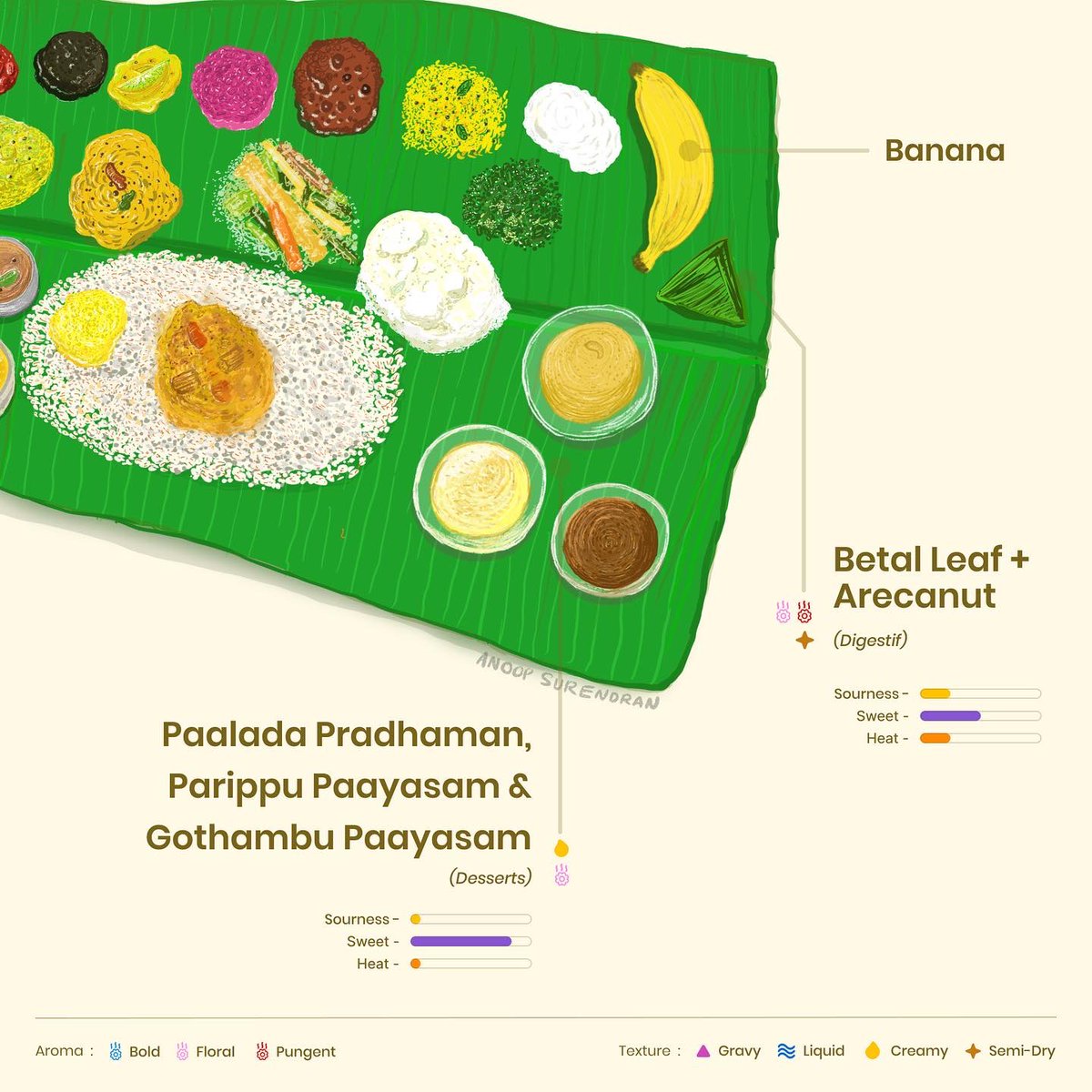

It’s fascinating that both the Sanskrit word "Thaila" and the Tamil word "Ennai", both referring to liquid fats (oils) come from words for a specific kind of oil - the one from the sesame seed. Thaila is what comes from Til and Ennai is Ellu Nei (fat from sesame)

So why is sesame such a significant thing in the Indian subcontinent? For starters, It turns out that it can grow in a wide variety of conditions, even on the edges of deserts.

So it’s not surprising that sesame has been a crucial crop in this part of the world for ~5000 years now, and it has survived massive climate change and wholesale civilizational shifts.

It also turns out that the sesame seed, from the plant Sesamum indicum is likely to be humanity’s earliest known plant source of fat. While we know that it was exported to Sumer and Akkad, it is even now rather central to funeral rites in this part of the world.

So the next question - what is a plant fat? To understand that, we first have to understand animal fats. Animal fat, usually found just under the skin, has been known for as long as Homo sapiens has hunted animals.

And ever since the discovery of fire, we’ve known that fat dripping into hot fire produces flavourful smoke that makes meat delicious. And we also know that cooking food in fats makes it way more delicious than food cooked in water.

So you might wonder why that is the case, and you’d be tempted to think that it has to do with fats reacting with food in ways water does not. And you’d be wrong. Fats don’t react with food.

The reason food cooked in fats is tastier is because water boils at 100C while cooking fats stay liquid up to 200C. What happens between 110 & 170C is the Maillard reaction where amino acids & sugars in the food react with each other to produce amazing flavours & brown colouring.

This is why almost every cuisine in the world starts dishes by heating some kind of fat in a cooking vessel. Being able to cook at above 100C is the central reason.

Which brings us to another question - so if the sesame oil you cooked your food in didn’t react with it, what happens to it? Good question - they simply go down your digestive system all the way to the small intestine, which is where they are digested.

Which raises this conundrum - fats don’t dissolve in water, and our bodies are mostly water, so how does this work? The answer is Bile - the yellow and green coloured liquid produced by our liver that acts as…an emulsifying agent.

Yep, your body literally turns fats into something like mayonnaise so that it can be broken down.

And those yellow and green pigments in bile? Guess what you get when you combine yellow and green colours? So now you know why 💩 is brown.

So the next logical question is - what actually happens when you “digest” fat. To understand that, we need to dig into what fats are made of.

A fat molecule (technically, a triglyceride) is made up of a glycerol backbone to which 3 fatty acids are attached, like 3 flags attached to a flagpole. Well, it begs the next question - what is a fatty acid?

A fatty acid is a chain of carbon atoms with a carboxyl group (O=C-OH) attached to one of the ends.

When the fatty acids only have single Carbon-Carbon bonds (Like C-C-C-C), they are considered “Saturated” because a single C-C bond can accommodate 6 C-H bonds. So the next question - what is a bond?

A bond is sub-atomic drug deal involving electrons. Some kinds of atoms are greedy for electrons and some are happy to provide them. A single bond involves the exchange of 1 electron and a double bond, 2 electrons.

Which brings us to the question at the end of the rabbit hole. Why do bonds happen? They happen because by sharing electrons, there is more stability in both atoms.

A Carbon atom can form single, double or triple bonds with another carbon atom. In a fatty acid, when there are double bonds, it’s said to be “unsaturated”.

This is because when there are only single bonds, the carbon atoms are “saturated” with Hydrogen. This is why when unsaturated fats are converted to saturated fats, that process is called ”Hydrogenation”. This is how you get Dalda/Vanaspati from liquid palm oil.

Most fats tend to have a mix of both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids and depending on the amount, they are either solids at room temperature or liquids.

Animal fats tend to have a greater percentage of saturated fatty acids, which makes them solid at room temperatures, which makes sense because animals tend to be solids at room temperature

Most plant sources of fat tend to have a higher percentage of unsaturated fats, which makes them liquids at room temperature.

In fact, it turns out that if you can figure out what fatty acids are there in fat from the skin of an animal, you can recognise the animal it came from, and this can be used to detect food fraud

If you recall a while back, horsemeat was found in packages labelled beef, and there is now a method to quickly detect if the biriyani you are eating is indeed made from poultry, and not, for instance, crow.

Depending on the number of C=C double bonds in the fatty acids that make up a fat molecule, you can get monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids. You should see these terms in nutritional information labels on consumer foods.

And depending on where the double bond is from the end of the molecule, and since Omega is the last letter of the Greek alphabet, chemists use Omega minus 3 and Omega minus 6 to describe fatty acids with double bonds at those positions

So yeah, Omega-3 is Omega minus 3, not hyphen 3.

So you might wonder why we bother to hydrogenate unsaturated fats into saturated fats when there is reasonable scientific consensus that unsaturated = good and saturated = cardiac arrest.

Well, it’s not that simple. Yes, a diet entirely made of saturated fats has been shown to have a correlation with heart disease, but it’s complicated.

There are cultures whose diets are entirely made of saturated fats and they have no problems (Kerala - Coconut oil, Inuits - Seal/whale blubber) so clearly, there are other factors (like genetics) at play.

Leaving aside the tricky subject of health, consider shelf life. Unsaturated fats are more volatile and unstable, and liquids tend to be harder to store and transport than compact solids. This is why we take liquid palm oil and “hydrogenate” it to become Dalda/Vanaspati.

A particularly delightful effect of the higher melting points of saturated fats is seen in chocolate, whose fats, called Cocoa butter (a.k.a. Theobroma oil) happen to melt around our body temperature, which is why chocolate has that characteristic “melt in the mouth” feeling

Knowing the melting point of cocoa butter is particularly useful when eating really dark chocolate (85%+ cocoa) which can be too bitter for a lot of people. There’s a good chance you store your chocolates in the fridge, so when you eat it, it’s likely around 5-10C.

So when eating dark chocolate, if you let it sit in your mouth for a few minutes, it will melt when it reaches 35C and will taste quite amazing. If you have never enjoyed dark chocolate, try this trick.

This is because a lot of biological systems rely on molecules “fitting” into neat little plug points made by larger molecules, and a plug-point designed for one configuration will not fit, for example, its mirror image.

Another kind of configuration variation is when molecules with the same component atoms have some groups of atoms arranged either across from each other or on opposite sides. This is what’s called cis and trans isomerism.

In the context of fats, we want the cis versions, not the trans versions of those molecules, and process of hydrogenation sometimes has the habit of producing trans versions of those molecules

This, in simple terms, is what a Trans-fat is, and long story short, there is enough research that tells us that they aren’t very good for cardiovascular health, which is why most countries ban the presence of trans fats in cooking mediums.

Another interesting fact is that fats themselves are largely neutral tasting but the individual fatty acids that make them up can be tremendously nasty tasting

What happens when you expose fats to sunlight, heat or oxygen is that over time, some of those fatty acids will break free from the glycerol backbone, and that’s when we say that the oil has turned rancid.

Which brings us to our final question - what’s the deal with refined & unrefined oils? When you press seeds to extract oil, you don’t get just the fat, you get other kinds of molecules that lend that fat its characteristic flavour & aroma. Fats, if you recall, are largely neutral

The refining process removes these non-fat molecules and gives you a less tasty, but longer-lasting product. One thing to keep in mind is that the “virgin” oil will have a lower “smoking point”, meaning that you shouldn’t be using it for deep frying

When virgin oils are heated to very high temperatures, those non-fat molecules start to break down earlier and could cause nasty after-tastes. Refined oils, on the other hand, can be safely used up to 200C.

We could keep going on, but then I'd rather you pre-ordered my upcoming book and learn how to master the use of fats in your cooking, among other things. Don't worry, the history bits are only for Twitter amazon.in/Masala-Lab-Sci…

Small correction (thanks to @sumants): A single bond involves the sharing of 2 electrons, a double bond, 4 electrons and so on.

And if you like watching cooking videos that focus on food science verified methods of making multiple dishes, here is the thread for that.

PS: The background music is custom made for each video and largely feature violin & cello in the lead

PS: The background music is custom made for each video and largely feature violin & cello in the lead

https://twitter.com/krishashok/status/1311678254462373888

And for anyone who faced the "out of stock" error, the pre-order link is now active! Kindly do the needful

If you want to go further into the Cuneiform rabbit hole, watch this hilariously entertaining 40-minute talk by Irving Finkel

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh