[THREAD: FROM TURTLES TO JANTAR MANTAR]

1/58

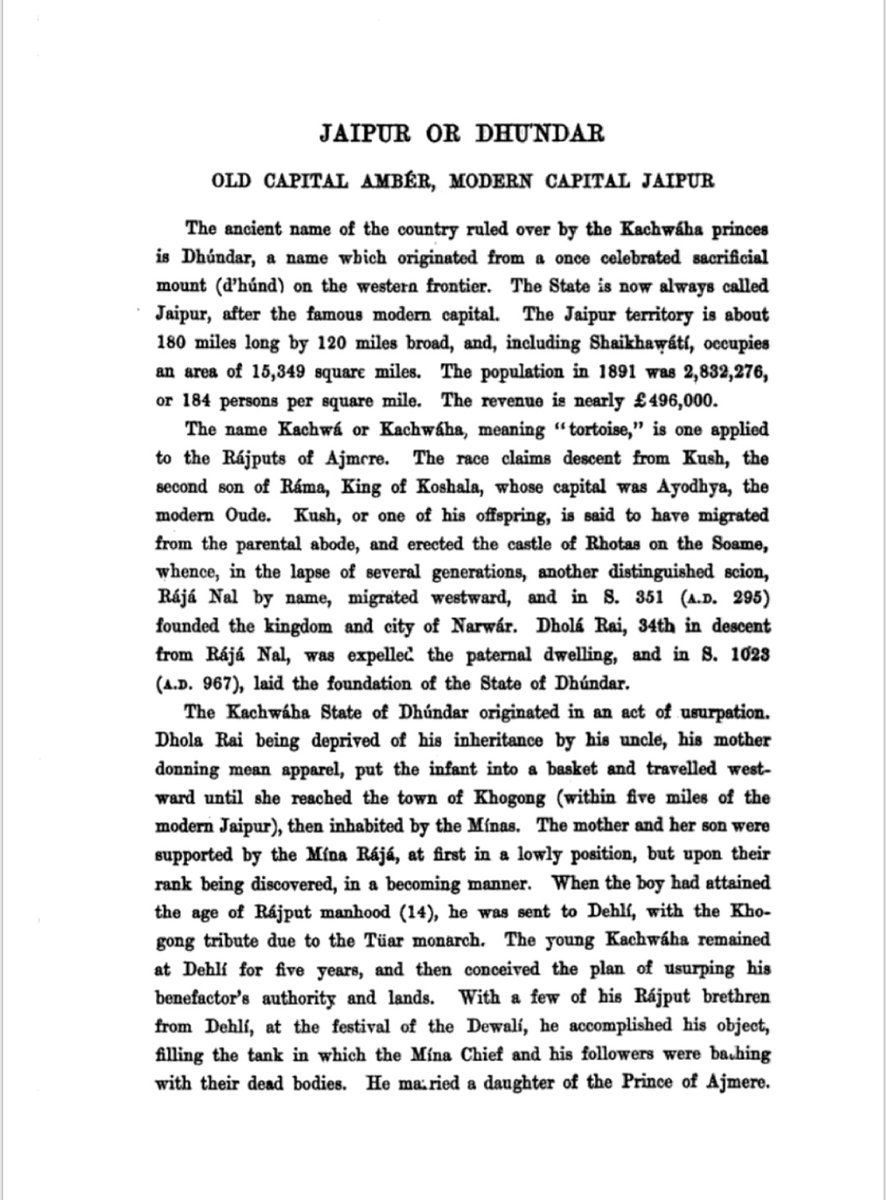

Long ago, a man got into a tiff with a turtle, kachhapa in Sanskrit. And emerged victorious, upon which he and his progeny assumed the title of Kachapaghat — literally, destroyer of turtles. With time, this corrupted to Kachwaha.

1/58

Long ago, a man got into a tiff with a turtle, kachhapa in Sanskrit. And emerged victorious, upon which he and his progeny assumed the title of Kachapaghat — literally, destroyer of turtles. With time, this corrupted to Kachwaha.

2/58

This, of course, is an etiological myth retrofitted to the clan's story around the 16th century to lend it a mystical aura.

There's one more, that traces the clan all the way to Kush, son of the mythical Hindu king, Ram. This is where the Kushwaha variant comes from.

This, of course, is an etiological myth retrofitted to the clan's story around the 16th century to lend it a mystical aura.

There's one more, that traces the clan all the way to Kush, son of the mythical Hindu king, Ram. This is where the Kushwaha variant comes from.

3/58

Origin myths notwithstanding, Kachwahas are Rajputs. At least that's how they've self-identified since medieval times.

The story of this dynasty, as recorded, goes back to the beginning of the 11th century when a Dulha Rai arrived in Rajputana, today's Rajasthan.

Origin myths notwithstanding, Kachwahas are Rajputs. At least that's how they've self-identified since medieval times.

The story of this dynasty, as recorded, goes back to the beginning of the 11th century when a Dulha Rai arrived in Rajputana, today's Rajasthan.

4/58

Those days, what's today Jaipur was Amber or Amer and it was the capital of Dhundhar. The territory belonged to local Meena rulers, a non-Rajput tribe native to the land. Dulha Rai managed to snag Amer, Dausa, and adjoining areas from the Meenas by 1093.

Those days, what's today Jaipur was Amber or Amer and it was the capital of Dhundhar. The territory belonged to local Meena rulers, a non-Rajput tribe native to the land. Dulha Rai managed to snag Amer, Dausa, and adjoining areas from the Meenas by 1093.

5/58

Thus begins the royal dynasty of the Kachwaha Rajputs. Dulha Rai governed Dhundhar from his capital at Amer.

All of this, of course, comes from oral accounts that were only later put to paper. Much, much later. Centuries later.

Thus begins the royal dynasty of the Kachwaha Rajputs. Dulha Rai governed Dhundhar from his capital at Amer.

All of this, of course, comes from oral accounts that were only later put to paper. Much, much later. Centuries later.

6/58

It's only with the advent of the Mughals in the 16th century that the Rajput story shows up in clear contemporary records, shedding much of bardic exaggerations that came with oral accounts. By mid-1200s, Ajmer was already home to a Muslim shrine, a dargah.

It's only with the advent of the Mughals in the 16th century that the Rajput story shows up in clear contemporary records, shedding much of bardic exaggerations that came with oral accounts. By mid-1200s, Ajmer was already home to a Muslim shrine, a dargah.

7/58

This dargah was a pilgrim staple to the subcontinent's Muslims which is why the Mughal rulers of Delhi would go to great lengths in securing a free passage from their capital in Delhi all the way to Ajmer, deep in the heart of Rajputana. This led to much conflict.

This dargah was a pilgrim staple to the subcontinent's Muslims which is why the Mughal rulers of Delhi would go to great lengths in securing a free passage from their capital in Delhi all the way to Ajmer, deep in the heart of Rajputana. This led to much conflict.

8/58

This pilgrim route cut right through what was then the kingdom of Amer. Yes, Amer and not Dhundhar. The kingdom was renamed after its capital some time in the 1300s. Amer those days swore allegiance to another Rajput dynasty, the kingdom of Marwar.

This pilgrim route cut right through what was then the kingdom of Amer. Yes, Amer and not Dhundhar. The kingdom was renamed after its capital some time in the 1300s. Amer those days swore allegiance to another Rajput dynasty, the kingdom of Marwar.

9/58

The constant Mughal-Mewar friction over the pilgrim route resulted in near-complete suzerainty of Akbar over Rajputana in general and Marwar in particular. Of course a sufi shrine alone, however important, couldn't be the sole reason for this campaign.

The constant Mughal-Mewar friction over the pilgrim route resulted in near-complete suzerainty of Akbar over Rajputana in general and Marwar in particular. Of course a sufi shrine alone, however important, couldn't be the sole reason for this campaign.

10/58

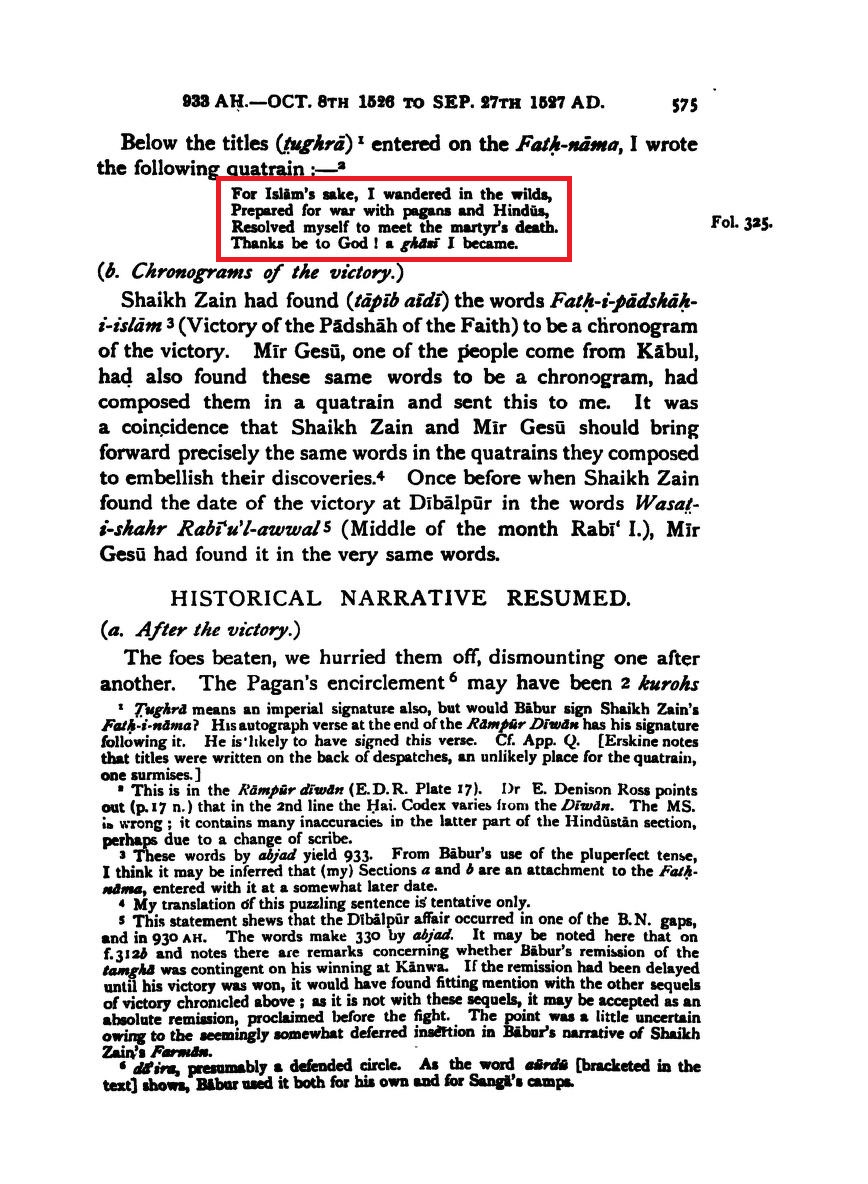

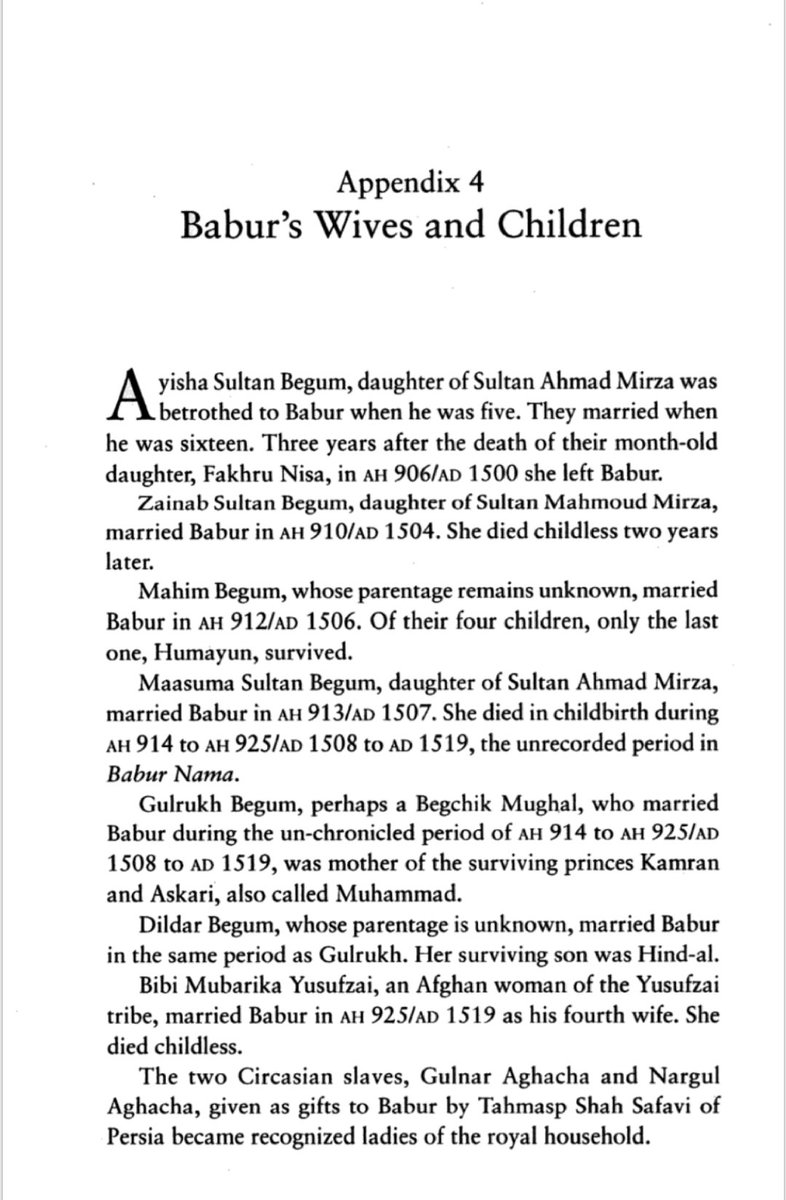

1503 saw Prithviraj Singh I take the throne as the sixteenth head of the Kachwaha dynasty. This man had quite the harem with no fewer than nine wives and 21 children. In comparison, his Muslim contemporary Babur never had more than 4 wives at once.

1503 saw Prithviraj Singh I take the throne as the sixteenth head of the Kachwaha dynasty. This man had quite the harem with no fewer than nine wives and 21 children. In comparison, his Muslim contemporary Babur never had more than 4 wives at once.

11/58

Prithviraj died fighting Babur in 1527. His only other achievement was bowing to neighbouring Mewar. After him, the throne went to one of his sons, Puranmal. Not because he was next in line but because his mom was his dad's favorite. This was problematic.

Prithviraj died fighting Babur in 1527. His only other achievement was bowing to neighbouring Mewar. After him, the throne went to one of his sons, Puranmal. Not because he was next in line but because his mom was his dad's favorite. This was problematic.

12/58

Puranmal's coronation was bitterly opposed by many including some of his own siblings. Dynastic infighting is always an opportunity. For the enemies. These enemies weren't Mughals, these were fellow Rajputs from the neighborhood. That's when a savior appeared.

Puranmal's coronation was bitterly opposed by many including some of his own siblings. Dynastic infighting is always an opportunity. For the enemies. These enemies weren't Mughals, these were fellow Rajputs from the neighborhood. That's when a savior appeared.

13/58

This savior, without whose help the dynasty wouldn't have survived the decade, was none other than the Mughal Emperor Humayun. This marked the beginning of a lasting friendship between Amer and the Mughals, one that transcended both Puranmal and Humayun.

This savior, without whose help the dynasty wouldn't have survived the decade, was none other than the Mughal Emperor Humayun. This marked the beginning of a lasting friendship between Amer and the Mughals, one that transcended both Puranmal and Humayun.

14/58

The word "friendship" here is a euphemism for the Kachwaha Rajputs' subservience to the Mughals. This was partly due to Humayun's favor, and partly due to pragmatism. Amer knew it was no match for the Mughal might, even with all the help from the rest of Rajputana.

The word "friendship" here is a euphemism for the Kachwaha Rajputs' subservience to the Mughals. This was partly due to Humayun's favor, and partly due to pragmatism. Amer knew it was no match for the Mughal might, even with all the help from the rest of Rajputana.

15/58

One key reason why the Rajputs didn't stand a chance before the Mughals was their absolute lack of unity. Sure, fratricides and betrayals were the norm in the Mughal Empire too, but they at least had gunpowder. The Rajputs had nothing but their swords and horses.

One key reason why the Rajputs didn't stand a chance before the Mughals was their absolute lack of unity. Sure, fratricides and betrayals were the norm in the Mughal Empire too, but they at least had gunpowder. The Rajputs had nothing but their swords and horses.

16/58

In just 7 quick years, Puranmal was tossed side by one of his brothers, Bhim Singh. Being the eldest in the family, Bhim Singh actually was the rightful heir to the throne. Puranmal's story doesn't end here though. He left behind a son who'll surface later.

In just 7 quick years, Puranmal was tossed side by one of his brothers, Bhim Singh. Being the eldest in the family, Bhim Singh actually was the rightful heir to the throne. Puranmal's story doesn't end here though. He left behind a son who'll surface later.

17/58

Bhim didn't last long on the throne though and died a mere 3 years into his reign. There's sources that even claim Bhim Singh aided in his own father's death but that remains ambiguous at best. That being said, knowing the times, not entirely improbable either.

Bhim didn't last long on the throne though and died a mere 3 years into his reign. There's sources that even claim Bhim Singh aided in his own father's death but that remains ambiguous at best. That being said, knowing the times, not entirely improbable either.

18/58

After Bhim came Ratan Singh who ran a crumbling Amer for a little over a decade. Ratan's reign was highlighted by two things — family feuds, and loss of sovereignty to a formidable new force from Afghanistan under a man named Sher Shah Suri.

After Bhim came Ratan Singh who ran a crumbling Amer for a little over a decade. Ratan's reign was highlighted by two things — family feuds, and loss of sovereignty to a formidable new force from Afghanistan under a man named Sher Shah Suri.

19/58

Why the Mughals didn't help Amer against Suri remains a mystery. But why the family itself couldn't unite against a common adversary isn't. Ratan Singh had 2 unacceptable problems — his alcoholism, and his foul language. Not the best of traits for a weak ruler anyway.

Why the Mughals didn't help Amer against Suri remains a mystery. But why the family itself couldn't unite against a common adversary isn't. Ratan Singh had 2 unacceptable problems — his alcoholism, and his foul language. Not the best of traits for a weak ruler anyway.

20/58

The entire family wanted this psychopath out. This included his uncles as well as his own younger brother, Askaran. Finally one day, the latter had the king poisoned to death and ascended to the throne. Again, knowing the times, not surprising at all.

The entire family wanted this psychopath out. This included his uncles as well as his own younger brother, Askaran. Finally one day, the latter had the king poisoned to death and ascended to the throne. Again, knowing the times, not surprising at all.

21/58

Askaran himself didn't last. A mere two weeks into his reign, the same uncle that had helped him against Ratan, helped himself to the throne. This uncle was Bharmal. But we'll come to him a little later. Let's dwell on the deposed raja a bit longer for now.

Askaran himself didn't last. A mere two weeks into his reign, the same uncle that had helped him against Ratan, helped himself to the throne. This uncle was Bharmal. But we'll come to him a little later. Let's dwell on the deposed raja a bit longer for now.

22/58

Having lost his throne, Askaran had nowhere left to go. In desperation, he sought help from the only family ally he could count on, the Mughals. The man in Delhi those days was none other than Akbar. But Akbar, being the emperor, didn't intervene directly.

Having lost his throne, Askaran had nowhere left to go. In desperation, he sought help from the only family ally he could count on, the Mughals. The man in Delhi those days was none other than Akbar. But Akbar, being the emperor, didn't intervene directly.

23/58

Instead, he appointed a local Rajputana governor named Haji Khan to mediate between the uncle and the nephew. The mediation worked and Ratan Singh ended up with a tiny principality of his own in Narwar in what's today Madhya Pradesh. Under Mughal suzerainty, of course.

Instead, he appointed a local Rajputana governor named Haji Khan to mediate between the uncle and the nephew. The mediation worked and Ratan Singh ended up with a tiny principality of his own in Narwar in what's today Madhya Pradesh. Under Mughal suzerainty, of course.

24/58

Ratan Singh went on to marry a Rathore princess from Marwar through whom he had, among other kids, a daughter named Manrang Devi. This girl, again, went on to marry a man from Marwar in keeping with what now looked like a family tradition. This man was Raja Udai Singh.

Ratan Singh went on to marry a Rathore princess from Marwar through whom he had, among other kids, a daughter named Manrang Devi. This girl, again, went on to marry a man from Marwar in keeping with what now looked like a family tradition. This man was Raja Udai Singh.

25/58

Manrang Devi and Uday Singh together had a daughter, they named her Manavati Baiji Lall Sahiba, later Jagat Gosain. But not for long. By the time she was 12, her father gave her away in marriage to a 16-year-old Jahangir after which she came to be known as Jodhabai.

Manrang Devi and Uday Singh together had a daughter, they named her Manavati Baiji Lall Sahiba, later Jagat Gosain. But not for long. By the time she was 12, her father gave her away in marriage to a 16-year-old Jahangir after which she came to be known as Jodhabai.

26/58

Don't confuse this Jodhabai with the other one from Akbar's harem. Jodhabai was a mere common noun given to Rajput wives in Mughal households because they came from Mewar, i.e. Jodhpur. Soon after marriage, Jahangir's Rajput wife gave birth to a healthy boy — Khurram.

Don't confuse this Jodhabai with the other one from Akbar's harem. Jodhabai was a mere common noun given to Rajput wives in Mughal households because they came from Mewar, i.e. Jodhpur. Soon after marriage, Jahangir's Rajput wife gave birth to a healthy boy — Khurram.

27/58

Khurram would later go on to inherit the throne from his dad as Shah Jahan.

Oh, we almost forgot Bharmal! Let's get back to Amer now. The last time we were there, Askaran had just been thrown out by uncle Bharmal and Mughal general had helped with reconciliations.

Khurram would later go on to inherit the throne from his dad as Shah Jahan.

Oh, we almost forgot Bharmal! Let's get back to Amer now. The last time we were there, Askaran had just been thrown out by uncle Bharmal and Mughal general had helped with reconciliations.

28/58

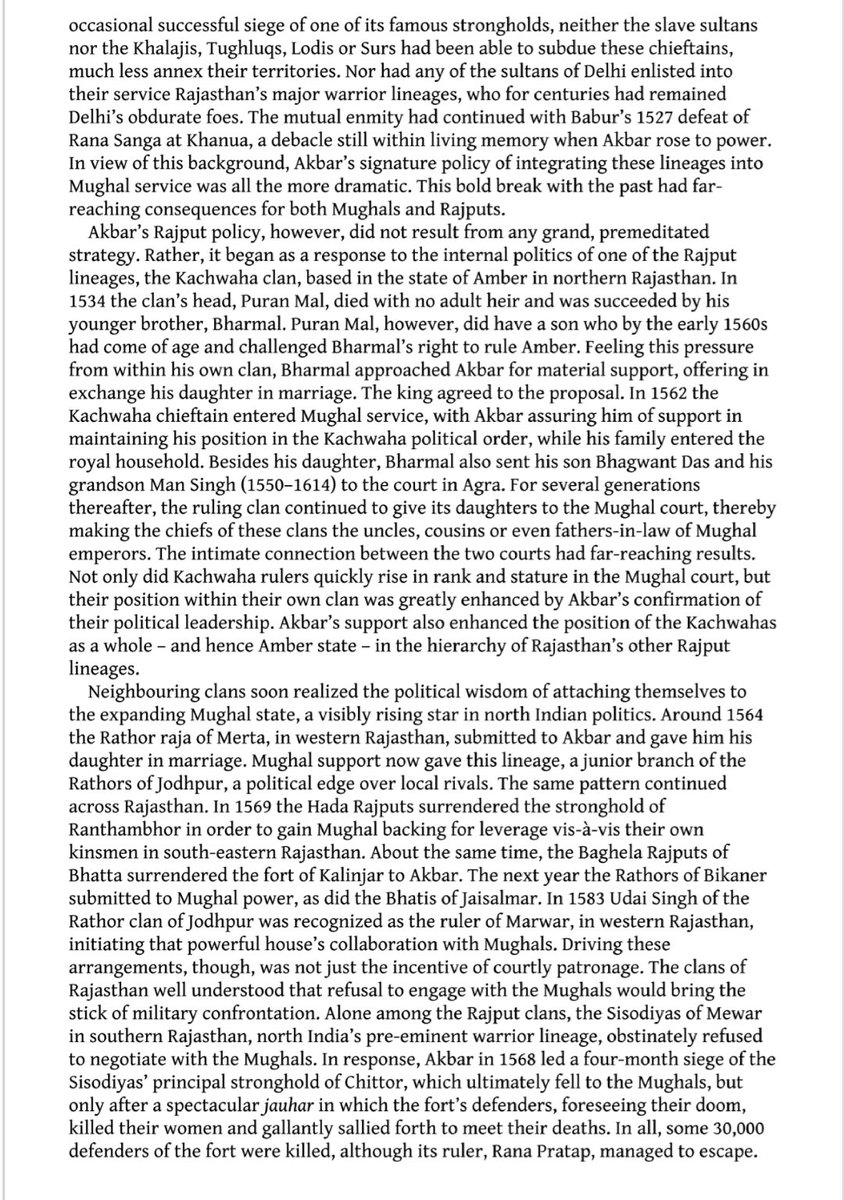

Bharmal's only claim to fame is his relationship with the Mughals, more specifically with one Mughal emperor. Bharmal had at least 8 kids from 3 wives. Of these 8 was a girl named Hira Kunwari. In 1562, Akbar appointed a new governor to Mewat. We'll come to him in a bit.

Bharmal's only claim to fame is his relationship with the Mughals, more specifically with one Mughal emperor. Bharmal had at least 8 kids from 3 wives. Of these 8 was a girl named Hira Kunwari. In 1562, Akbar appointed a new governor to Mewat. We'll come to him in a bit.

29/58

At this point let's quickly recap what we've had so far. At first was Prithviraj Singh I who had 21 kids. The eldest was Bhim Singh, but the favorite was Puranmal. The eldest should've succeeded, but the throne went to the favorite. Puranmal became the new king.

At this point let's quickly recap what we've had so far. At first was Prithviraj Singh I who had 21 kids. The eldest was Bhim Singh, but the favorite was Puranmal. The eldest should've succeeded, but the throne went to the favorite. Puranmal became the new king.

30/58

Puranmal died in unclear circumstances albeit there's speculations stepbrother Bhim Singh had a hand in it. Nevertheless, the throne reverted to the rightful heir, the eldest son of Prithviraj, Bhim Singh. He was later succeeded by Ratan Singh, his eldest.

Puranmal died in unclear circumstances albeit there's speculations stepbrother Bhim Singh had a hand in it. Nevertheless, the throne reverted to the rightful heir, the eldest son of Prithviraj, Bhim Singh. He was later succeeded by Ratan Singh, his eldest.

31/58

But Ratan Singh was a jerk, so his folks got rid of him and placed younger brother Askaran in the throne. Askaran was helped by Bharmal, one of Bhim Singh's brothers. Two weeks later, uncle Bharmal threw out his nephew and became the new king. This is where we are now.

But Ratan Singh was a jerk, so his folks got rid of him and placed younger brother Askaran in the throne. Askaran was helped by Bharmal, one of Bhim Singh's brothers. Two weeks later, uncle Bharmal threw out his nephew and became the new king. This is where we are now.

32/58

If you noticed, Bharmal, Bhim Singh, and Puranmal were all siblings. Let's rewind to Puranmal for a minute. Remember I said he had a son who'd surface later? Well, now it's when he does. You see, there's several theories on how Puranmal died.

If you noticed, Bharmal, Bhim Singh, and Puranmal were all siblings. Let's rewind to Puranmal for a minute. Remember I said he had a son who'd surface later? Well, now it's when he does. You see, there's several theories on how Puranmal died.

33/58

Some say he died fighting for Humayun. Others say he died fighting Hindal. Yet others say he was overthrown by elder brother Bhim. And some allege fratricide — that Bhim Singh didn't just oust him, but had him killed. Whatever be the case, Puranmal had a son.

Some say he died fighting for Humayun. Others say he died fighting Hindal. Yet others say he was overthrown by elder brother Bhim. And some allege fratricide — that Bhim Singh didn't just oust him, but had him killed. Whatever be the case, Puranmal had a son.

34/58

In Mahabharata, Pandu was elder but Dhritrashtra was king. So when the newer generation came of age, there was a succession dilemma. The Pandavas staked claim because their father ought to have been the king. But Kauravas wouldn't relent because theirs WAS the king.

In Mahabharata, Pandu was elder but Dhritrashtra was king. So when the newer generation came of age, there was a succession dilemma. The Pandavas staked claim because their father ought to have been the king. But Kauravas wouldn't relent because theirs WAS the king.

35/58

Same thing happened here. Bharmal was the king now. But Puranmal was once. And after Puranmal, the throne ought to have gone to his son, Sujamal. It didn't because he was still a minor at the time. Now Sujamal was a grown man. And he wanted what was rightfully his.

Same thing happened here. Bharmal was the king now. But Puranmal was once. And after Puranmal, the throne ought to have gone to his son, Sujamal. It didn't because he was still a minor at the time. Now Sujamal was a grown man. And he wanted what was rightfully his.

36/58

Bharmal, in his defense, didn't consider Sujamal the rightful heir to Puranmal because the latter himself was not the rightful heir to Prithviraj. So Sujamal plotted his move. Remember the new governor Akbar appointed to Mewat? It was Mirza Muhammad Sharaf-ud-din Hussain.

Bharmal, in his defense, didn't consider Sujamal the rightful heir to Puranmal because the latter himself was not the rightful heir to Prithviraj. So Sujamal plotted his move. Remember the new governor Akbar appointed to Mewat? It was Mirza Muhammad Sharaf-ud-din Hussain.

37/58

Sujamal reached out to Hussain and discussed his plan. It worked. Hussain marched on Amer and seeing his troops, Bharmal surrendered without even a fight. Not only surrendered, he agreed to pay a tribute to the Mughal governor. As collateral, he offered his own son.

Sujamal reached out to Hussain and discussed his plan. It worked. Hussain marched on Amer and seeing his troops, Bharmal surrendered without even a fight. Not only surrendered, he agreed to pay a tribute to the Mughal governor. As collateral, he offered his own son.

38/58

But the Mughal governor wasn't done yet. Word reached Bharmal of a second invasion. This time, the Rajput king reached out to the emperor in Agra, Akbar. The emperor agreed to help and had a little talk with his governor. Amer was restored to Bharmal. As was his son.

But the Mughal governor wasn't done yet. Word reached Bharmal of a second invasion. This time, the Rajput king reached out to the emperor in Agra, Akbar. The emperor agreed to help and had a little talk with his governor. Amer was restored to Bharmal. As was his son.

39/58

Bharmal returned the favor — and it was a massive favor — by offering his daughter to the emperor in marriage. This was none other than Hira Kunwari, popularly known as Jodhabai. Don't confuse her with her daughter-in-law (Jahangir's Jodhabai) though.

Bharmal returned the favor — and it was a massive favor — by offering his daughter to the emperor in marriage. This was none other than Hira Kunwari, popularly known as Jodhabai. Don't confuse her with her daughter-in-law (Jahangir's Jodhabai) though.

40/58

Marrying daughters off to the Mughals was almost becoming a family tradition among the Rajputs of Amer. Bharmal was succeeded in 1574 by his son, Bhagwant Das. Besides being the king of Amer, Bhagwant Das was also one of Akbar's most trusted generals.

Marrying daughters off to the Mughals was almost becoming a family tradition among the Rajputs of Amer. Bharmal was succeeded in 1574 by his son, Bhagwant Das. Besides being the king of Amer, Bhagwant Das was also one of Akbar's most trusted generals.

41/58

Bhagwant Das served the Mughal emperor in campaigns in places like Afghanistan, Punjab, and even Kashmir. His loyalty and bravery earned him the title Amir-ul-Umra. He also had a daughter, Manbhawati Bai. In 1585, when she was only 15, her father gave her away in marriage.

Bhagwant Das served the Mughal emperor in campaigns in places like Afghanistan, Punjab, and even Kashmir. His loyalty and bravery earned him the title Amir-ul-Umra. He also had a daughter, Manbhawati Bai. In 1585, when she was only 15, her father gave her away in marriage.

42/58

The groom was none other than Akbar's son, Prince Salim, later Emperor Jahangir. Shah Begum, as the girl came to be referred to as after marriage, was the first Rajput woman in Jahangir's harem. The following year, she was joined by a second, Jagat Gosain.

The groom was none other than Akbar's son, Prince Salim, later Emperor Jahangir. Shah Begum, as the girl came to be referred to as after marriage, was the first Rajput woman in Jahangir's harem. The following year, she was joined by a second, Jagat Gosain.

43/58

Bhagwant Das was succeeded by his son, Man Singh I who was also a trusted general in Akbar's service, just like his dad. Man Singh even went on to become one of the Mughal court's Navaratnas. Akbar conferred upon him the title Mirza right after the latter's coronation.

Bhagwant Das was succeeded by his son, Man Singh I who was also a trusted general in Akbar's service, just like his dad. Man Singh even went on to become one of the Mughal court's Navaratnas. Akbar conferred upon him the title Mirza right after the latter's coronation.

44/58

Man Singh further crystallized his esteem in the Mughal court by leading his troops against Maharana Pratap in the Battle of Haldighati. Pratap managed to escape but the battle ended in a decisive Mughal victory. This brought Mewar into Akbar's fold.

Man Singh further crystallized his esteem in the Mughal court by leading his troops against Maharana Pratap in the Battle of Haldighati. Pratap managed to escape but the battle ended in a decisive Mughal victory. This brought Mewar into Akbar's fold.

45/58

Upon Man Singh's death in 1614, the throne went to his younger son, Bhau Singh. It ought to have gone to Jagat Singh but he was dead. Even then, Hindu primogeniture dictated that the throne then go to Jagat Singh's son, Maha Singh. But that was overruled by Jahangir.

Upon Man Singh's death in 1614, the throne went to his younger son, Bhau Singh. It ought to have gone to Jagat Singh but he was dead. Even then, Hindu primogeniture dictated that the throne then go to Jagat Singh's son, Maha Singh. But that was overruled by Jahangir.

46/58

Subservient to Mughal diktat, the Kachwahas had no choice but to accept Bhau Singh on the throne. Problem with Bhau Singh was, he was a terrible warrior. And a bundle of nerves. This was illustrated when Jahangir sent him on an expedition against Malik Ambar.

Subservient to Mughal diktat, the Kachwahas had no choice but to accept Bhau Singh on the throne. Problem with Bhau Singh was, he was a terrible warrior. And a bundle of nerves. This was illustrated when Jahangir sent him on an expedition against Malik Ambar.

47/58

Malik Ambar was a Muslim ruler in the Deccan who was initially brought to India as a slave from Africa. He had been a pain in the neck for the Mughals for a while now and Jahangir hoped a Rajput force led by the Kachwaha king would end the problem once and for all.

Malik Ambar was a Muslim ruler in the Deccan who was initially brought to India as a slave from Africa. He had been a pain in the neck for the Mughals for a while now and Jahangir hoped a Rajput force led by the Kachwaha king would end the problem once and for all.

48/58

But that didn't happen. Bhau Singh's military prowess proved no match for the slave king's guerrilla strategies. This failure cost him a lot of esteem in the Mughal court which in turn drove him into depression and alcoholism. He would never recover from this.

But that didn't happen. Bhau Singh's military prowess proved no match for the slave king's guerrilla strategies. This failure cost him a lot of esteem in the Mughal court which in turn drove him into depression and alcoholism. He would never recover from this.

49/58

After Bhau Singh's premature death, Jahangir appointed a 10-year-old Jai Singh I to the throne. He was not the direct heir but since Bhau Singh left without a progeny, there was no alternative. Jai Singh's tenure spanned the entirety of Shah Jahan's reign and further.

After Bhau Singh's premature death, Jahangir appointed a 10-year-old Jai Singh I to the throne. He was not the direct heir but since Bhau Singh left without a progeny, there was no alternative. Jai Singh's tenure spanned the entirety of Shah Jahan's reign and further.

50/58

The power struggle that followed in the Mughal court after Shah Jahan's health went into decline saw the emergence of two key players — Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. Dara was a great administrator and refreshingly secular. But a terrible military leader.

The power struggle that followed in the Mughal court after Shah Jahan's health went into decline saw the emergence of two key players — Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. Dara was a great administrator and refreshingly secular. But a terrible military leader.

51/58

Aurangzeb, on the other hand, was a great military leader and a ruthless administrator, but suffocatingly theocratic. It was almost a good vs. evil tug-of-war in which Aurangzeb emerged victorious. Jai Singh happened to be loyal to Aurangzeb. Wise call.

Aurangzeb, on the other hand, was a great military leader and a ruthless administrator, but suffocatingly theocratic. It was almost a good vs. evil tug-of-war in which Aurangzeb emerged victorious. Jai Singh happened to be loyal to Aurangzeb. Wise call.

52/58

Jai Singh's successor was Ram Singh the only highlight of whose reign was being sent by Aurangzeb to invade the Ahom king of Assam, a humiliating defeat, and the subsequent disgrace in the Mughal Emperor's books.

Jai Singh's successor was Ram Singh the only highlight of whose reign was being sent by Aurangzeb to invade the Ahom king of Assam, a humiliating defeat, and the subsequent disgrace in the Mughal Emperor's books.

53/58

After Jai Singh I came Bishen Singh who managed to dodge Aurangzeb's orders to fight for him in the Deccan by bribing and groveling. Aurangzeb finally relented but only in the condition that he send his son Jai Singh II in his stead.

After Jai Singh I came Bishen Singh who managed to dodge Aurangzeb's orders to fight for him in the Deccan by bribing and groveling. Aurangzeb finally relented but only in the condition that he send his son Jai Singh II in his stead.

54/58

After a series of disgraceful reigns, Jai Singh II's was the first in a long time to win back some of the lost Mughal esteem. Aurangzeb, impressed by both his military prowess as well as his wit, conferred upon him the title of Sawai, equivalent to a king and a quarter.

After a series of disgraceful reigns, Jai Singh II's was the first in a long time to win back some of the lost Mughal esteem. Aurangzeb, impressed by both his military prowess as well as his wit, conferred upon him the title of Sawai, equivalent to a king and a quarter.

55/58

And that's how we Jai Singh II became Sawai Jai Singh, a practice his descendants would continue long after him. In 1727, he established a new township close to Amer as his new capital, and called it Jaipur. His other claim to fame comes from his interest in astronomy.

And that's how we Jai Singh II became Sawai Jai Singh, a practice his descendants would continue long after him. In 1727, he established a new township close to Amer as his new capital, and called it Jaipur. His other claim to fame comes from his interest in astronomy.

56/58

This interest in astronomy results in a series of observatories in Jaipur, Delhi, and some other cities. We know them as Jantar Mantars. Sawai Jai Singh's reign marks the high point of Kachwaha power and saw the dynasty finally decouple from Mughal hegemony.

This interest in astronomy results in a series of observatories in Jaipur, Delhi, and some other cities. We know them as Jantar Mantars. Sawai Jai Singh's reign marks the high point of Kachwaha power and saw the dynasty finally decouple from Mughal hegemony.

57/58

The dynasty continues till today and its heads still serve as titular rulers of Jaipur. Throughout its history, the dynasty gave at the very least three big-ticket daughters to the Mughals in marriage. Happily and under no duress. No love jihad.

The dynasty continues till today and its heads still serve as titular rulers of Jaipur. Throughout its history, the dynasty gave at the very least three big-ticket daughters to the Mughals in marriage. Happily and under no duress. No love jihad.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh