Whether you’re the parent of a toddler (or an adolescent) or, like @WelshGasDoc, an overtired shiftworker, many people know the frustration of trying to get themselves or someone else to sleep but, no matter how tired they seem, they just won’t do it

Sleep has rhythms

Sleep has rhythms

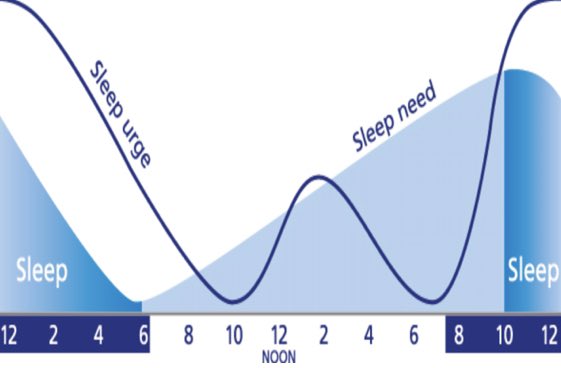

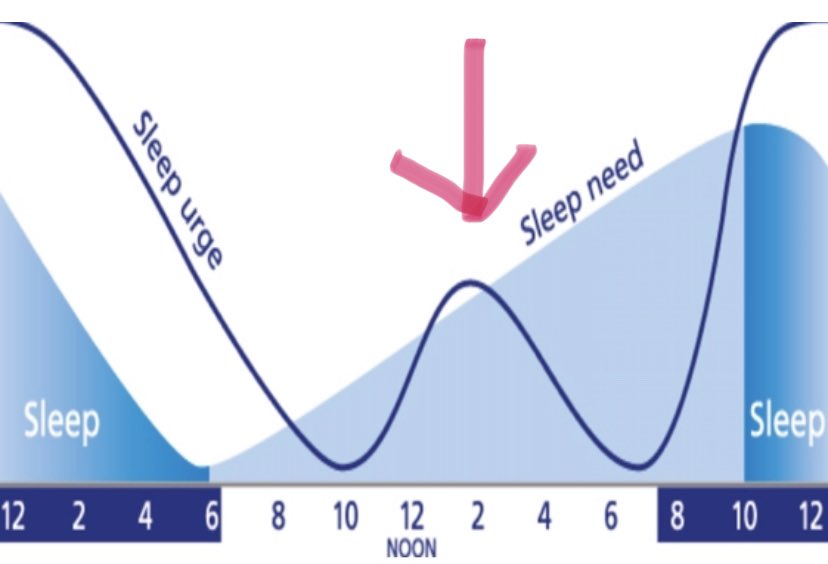

How sleepy we feel, and how much we *need* to sleep don’t always match up

The simplest example of this is the post-lunch sleepiness many of us feel

Even if we don’t sleep, we usually feel *less* tired a few hours later when we’ve been awake longer

Weird, huh?

The simplest example of this is the post-lunch sleepiness many of us feel

Even if we don’t sleep, we usually feel *less* tired a few hours later when we’ve been awake longer

Weird, huh?

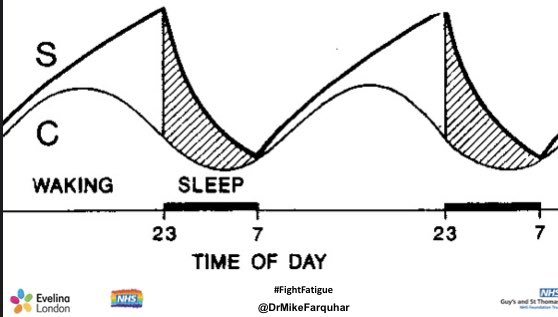

Sleep is a complex process, but we can simplify how we think about it into what is called the “two process” model of sleep

This describes sleep/wake as the interaction of two elements: Sleep Pressure (S), and Circadian Rhythm (C)

This describes sleep/wake as the interaction of two elements: Sleep Pressure (S), and Circadian Rhythm (C)

Sleep Pressure is like hunger for sleep: just as the longer you haven’t eaten the hungrier you will be, the longer you’ve been awake the more Sleep Pressure there is

Sleep Pressure builds fairly linearly, from the moment you wake up until you fall asleep

Sleep Pressure builds fairly linearly, from the moment you wake up until you fall asleep

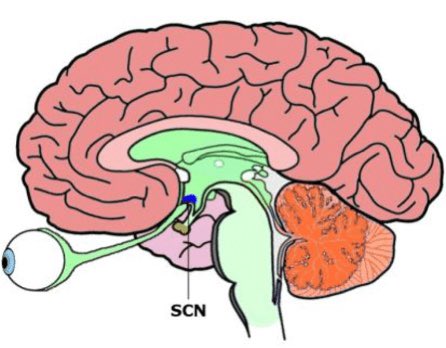

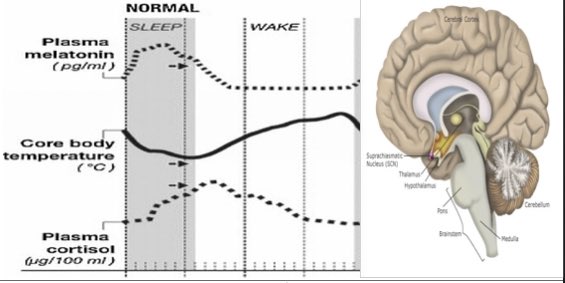

Your Circadian Rhythm is your internal body clock, that regulates the timing of your body’s activities

The master clock is in the suprachismatic nucleus in the hypothalamus in your brain, but there is circadian circuitry in every cell in your body

The master clock is in the suprachismatic nucleus in the hypothalamus in your brain, but there is circadian circuitry in every cell in your body

Many of your body’s rhythms are controlled or influenced by the circadian clock - variation in core measurements like heart rate, blood pressure or temperature for example, or the timing of release of hormones like melatonin (more on which later) or cortisol

For humans, our body clock, very generally, is set to keep us awake in the day and asleep at night

There is individual variation in this, which is why some people are morning “larks” and some night “owls”, but...

There is individual variation in this, which is why some people are morning “larks” and some night “owls”, but...

... we are essentially wired to be sound asleep in the middle of the night

This, of course, is why working a nightshift is inherently unnatural, and underpins a lot of the work I’ve done over the years about helping shiftworkers to cope better with that

ep.bmj.com/content/102/3/…

This, of course, is why working a nightshift is inherently unnatural, and underpins a lot of the work I’ve done over the years about helping shiftworkers to cope better with that

ep.bmj.com/content/102/3/…

Being out of sync with our body clocks is something people can be familiar with due to jet lag, which is effectively the symptoms created when we’re trying to force our brains and bodies to do the opposite of what our body clock is telling us to do

Your circadian drive is STRONG

Your circadian drive is STRONG

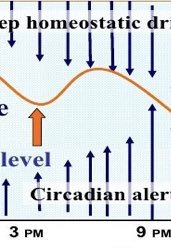

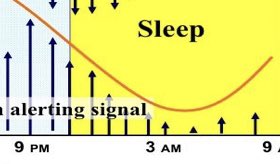

During waking hours, our circadian drive is set to help us stay awake

You can think of it doing this by sending an alerting signal from your brain to the rest of your body saying “you’re meant to be awake now!”

(It’s like internal Red Bull 😁)

You can think of it doing this by sending an alerting signal from your brain to the rest of your body saying “you’re meant to be awake now!”

(It’s like internal Red Bull 😁)

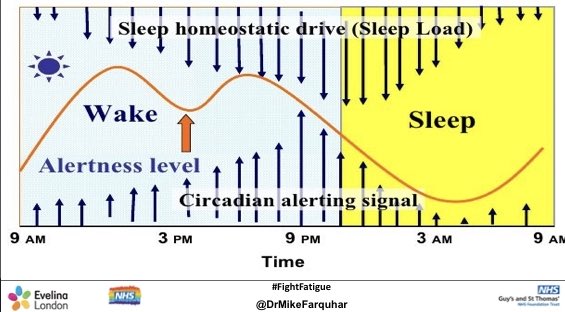

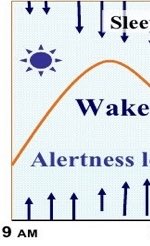

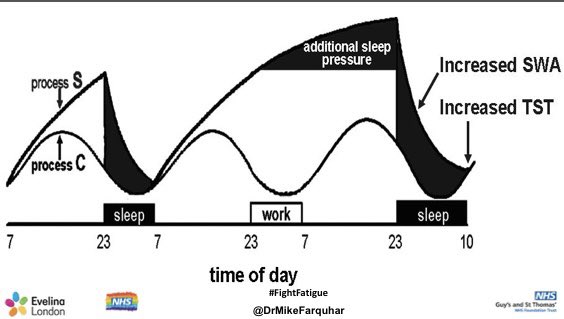

So ... how do Sleep Pressure and Circadian Rhythm interact over 24 hours

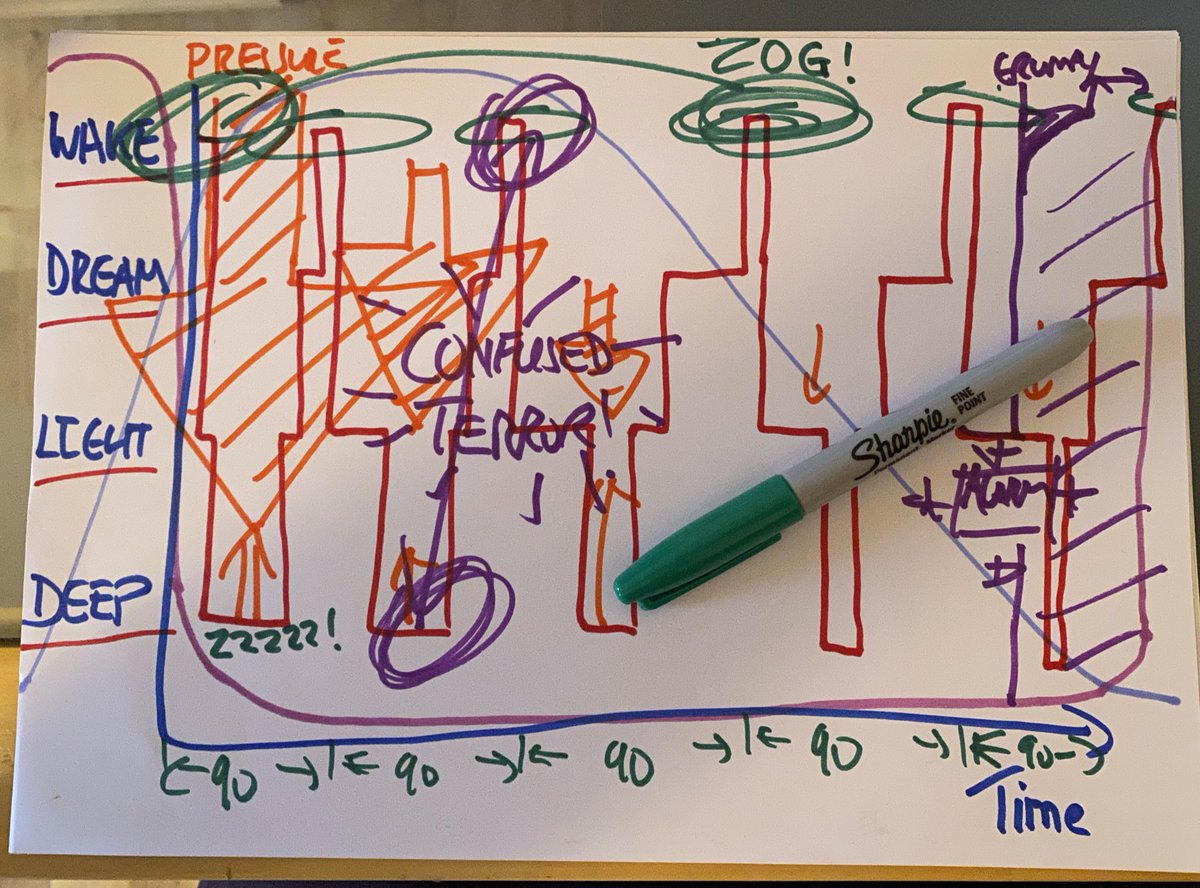

It’s not quite as simple as it might first look ... let’s walk through this diagram

It’s not quite as simple as it might first look ... let’s walk through this diagram

Let’s assume (!) you’ve had a good night’s sleep

You’ve woken up bright and breezy

Your sleep pressure is LOW

Your circadian clock is in WAKE mode, but doesn’t really need to do very much to help you because you’re not tired, so the alerting signal is relatively weak

You’ve woken up bright and breezy

Your sleep pressure is LOW

Your circadian clock is in WAKE mode, but doesn’t really need to do very much to help you because you’re not tired, so the alerting signal is relatively weak

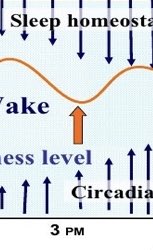

As the day goes on, your sleep pressure consistently builds up, and your body clock responds by increasing the alerting signal - this keeps you consistently functioning at roughly the same level of alertness

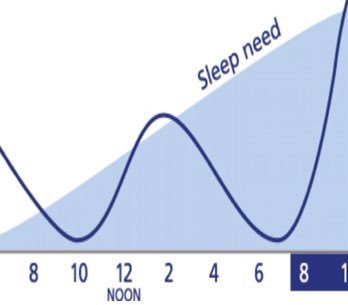

Just after lunchtime though, we meet a quirk: the alerting signal doesn’t quite keep pace with the steadily increasing sleep pressure

This means in the tug-of-war between sleep pressure and circadian drive, sleep pressure is winning ... and you feel more tired

This means in the tug-of-war between sleep pressure and circadian drive, sleep pressure is winning ... and you feel more tired

This (partly) explains that post-lunch sleepiness, which some cultures still exploit to have an afternoon siesta

Why does it happen? We can speculate that, in evolutionary terms, avoiding the midday sun may have been beneficial, so we evolved to retreat and be less active then

Why does it happen? We can speculate that, in evolutionary terms, avoiding the midday sun may have been beneficial, so we evolved to retreat and be less active then

By late afternoon though, the Circadian Drive is back on it, and starts to ⬆️ alerting signal strength, all the way to bedtime, countering the (by now) quite strong effect of Sleep Pressure

So, you can often feel much more awake in the evening, even if you’ve felt tired earlier

So, you can often feel much more awake in the evening, even if you’ve felt tired earlier

As we near bedtime, its job done, the alerting signal starts to drop away, leaving Sleep Pressure unopposed ... which means it’s time to go to sleep

As we go through the night, the alerting signal drops to pretty much zero, reaching its nadir around 3am

As we go through the night, the alerting signal drops to pretty much zero, reaching its nadir around 3am

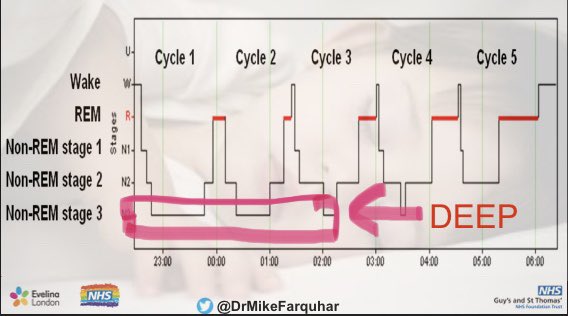

Sleep Pressure removed by deep sleep, mainly occurring in first third of night

Alerting signal ⬇️ to zero is one of the things that helps us stay asleep, even though Sleep Pressure has now ⬇️

We then get a morning circadian kick, partly cortisol mediated, to help start our day

Alerting signal ⬇️ to zero is one of the things that helps us stay asleep, even though Sleep Pressure has now ⬇️

We then get a morning circadian kick, partly cortisol mediated, to help start our day

There are other things going on though ...

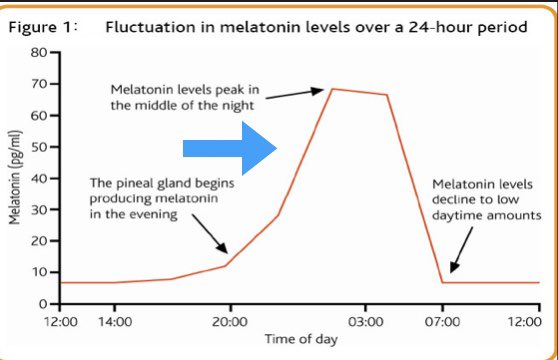

At the end of the day, other things are helping us get into sleep

One of these is melatonin, whose release is triggered by the body clock as environmental light levels fall

At the end of the day, other things are helping us get into sleep

One of these is melatonin, whose release is triggered by the body clock as environmental light levels fall

The simplest way to think about melatonin is that it is a message from your brain to the rest of your body saying “it’s time to go to sleep now”

For most adults, its effect will kick in between 10-11 at night

Its effect though is quite easily over-ridden, and any benefit lost

For most adults, its effect will kick in between 10-11 at night

Its effect though is quite easily over-ridden, and any benefit lost

When everything lines up: ⬆️Sleep Pressure, ⬇️Circadian Alerting Signal, effect of melatonin, the “perfect” circumstances are created for us to fall asleep

It creates a window of opportunity when our chance of getting to sleep is at its highest

It creates a window of opportunity when our chance of getting to sleep is at its highest

If we miss that opportunity though ... we can get overtired and, just like an exhausted toddler, once we’re out of the window, many of us struggle *more* to get to sleep, which makes us frustrated and anxious, which makes getting to sleep even harder

We all have an ideal internal bedtime, unique to us

If we organise our routine so that we’re trying to go to bed at that time, we’re most likely to sleep well

If we create routines when we’re trying to go to sleep outside our natural sleep onset window, things become trickier

If we organise our routine so that we’re trying to go to bed at that time, we’re most likely to sleep well

If we create routines when we’re trying to go to sleep outside our natural sleep onset window, things become trickier

A trap parents can easily fall into is trying to send a child to bed too early

If your toddler’s brain is set to fall asleep at 8pm, but you try to send them to bed at 7, it’s likely to fail ... because their circadian alerting signal is still relatively high

If your toddler’s brain is set to fall asleep at 8pm, but you try to send them to bed at 7, it’s likely to fail ... because their circadian alerting signal is still relatively high

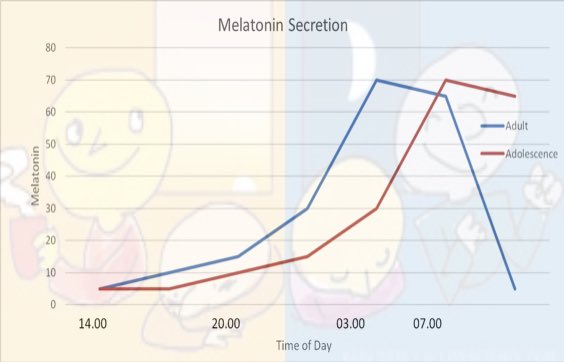

This is also true of adolescents, whose body clocks all shift later, so telling them to go to sleep at 10pm when their body clocks are still in full ALERT mode means they just become frustrated at not being able to sleep

(You can read more about adolescent sleep physiology, and how poor understanding of this by adults often leaves adolescents feeling frustrated about sleep, here:

twitter.com/i/events/10550… )

twitter.com/i/events/10550… )

We also need to think about light

The internal circadian clock is regulated by a host of things, but the strongest of these is light

We evolved to be awake in the daytime and asleep at night, and that rhythm was set by the varying pattern of natural light over 24 hours

The internal circadian clock is regulated by a host of things, but the strongest of these is light

We evolved to be awake in the daytime and asleep at night, and that rhythm was set by the varying pattern of natural light over 24 hours

When you travel the world (remember when we could do that!) and become jetlagged, the symptoms reduce over a few days as your body responds to the pattern of environmental light and rewires your body clock to match

Light has a huge influence on circadian timing

Light has a huge influence on circadian timing

While our individual bedtime is set to a degree by our genetics, there are environmental factors which affect it as well, and light is one of the strongest

In toddlers, around a quarter of the variance in bedtimes is explained by how much light they are exposed to in the evening

In toddlers, around a quarter of the variance in bedtimes is explained by how much light they are exposed to in the evening

Evening light affects sleep onset:

- it “tells” your brain it should be awake

- it suppresses melatonin production

- it will encourage your internal clock to rewrite to a later time, so sleep onset will be delayed

All of that means too much evening light is bad for sleep!

- it “tells” your brain it should be awake

- it suppresses melatonin production

- it will encourage your internal clock to rewrite to a later time, so sleep onset will be delayed

All of that means too much evening light is bad for sleep!

Other quirks:

Caffeine temporarily blocks Sleep Pressure (by blocking effect of adenosine, one of the components of Sleep Pressure)

It does not *remove* the Sleep Pressure so, when the caffeine wears off, it will hit you with a bang again

Used judiciously, caffeine can help

Caffeine temporarily blocks Sleep Pressure (by blocking effect of adenosine, one of the components of Sleep Pressure)

It does not *remove* the Sleep Pressure so, when the caffeine wears off, it will hit you with a bang again

Used judiciously, caffeine can help

Understanding the interaction of Sleep Pressure and Circadian Rhythm also helps understand how people feel when working nights

This person is coming to do a nightshift having been awake since 7am

When they arrive at work, they feel ok - S is high, but so is the alerting signal

This person is coming to do a nightshift having been awake since 7am

When they arrive at work, they feel ok - S is high, but so is the alerting signal

Adrenaline, caffeine, the last of the alerting signal will help them surf the first few hours of the night

By 3am, with Sleep Pressure high and the circadian alerting signal at zero, they feel utterly awful

By 3am, with Sleep Pressure high and the circadian alerting signal at zero, they feel utterly awful

By 7am though, you’re feeling a bit better - partly the psychological kick of knowing the shift is almost over but physiologically because the alerting signal js back, telling you it’s time to to wake up

(plus, if you’re lucky, ... NHS TOAST!)

(plus, if you’re lucky, ... NHS TOAST!)

It’s a false dawn though - you feel better than you objectively are, and critical functions, like your reaction time, will be impaired by that stonkingly high sleep pressure

It’s why shiftworkers are so at risk of traffic accidents

It’s why shiftworkers are so at risk of traffic accidents

Your best chance of getting to sleep after a night shift is as soon as possible, before the alerting signal gets too high and starts to frustrate your efforts ... which is why we should do rapid handovers at shift end to get our teams home to bed ASAP

All of this is an oversimplification of what’s actually happening but it is (I hope!) a useful way to conceptualise how wake and sleep are regulated

Thinking about these principles can help you to work out your own (or your toddler’s...) optimal times for sleep

Thinking about these principles can help you to work out your own (or your toddler’s...) optimal times for sleep

For any of us, learning to read the cues that help us work out our natural sleep times (or if you’re a parent, your child’s sleep cues) is really important

For good sleep, we need a sleep routine that works *with* our own unique physiology, not against it

For good sleep, we need a sleep routine that works *with* our own unique physiology, not against it

Children, young people and families who come to see me in my @EvelinaLondon sleep clinic usually get a version of this explanation performed in the medium of Sharpie 😁

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh