A story of inappropriate technology: in the 1970s it was decided to modernize the rice farming of Sri Lanka, whose system that had not changed much for 3000 years. The goal was to replace the water buffalo with the modern tractor, but the attempt had disastrous consequences...

Buffalos create "wallows", pools of muddy water without which they cannot control their temperatures. Always filled with water, these wallows create many eco-services: in the dry season the become a haven for fish that then migrate back to the paddies when these fill with water.

The fish is a valuable source of proteins for landless laborers and greatly help control the population of malaria causing mosquitoes who breed in the rice paddies. The vegetation around the wallows are breeding and hunting grounds for snakes and water monitor lizards who prey...

...on rats that eat the rice and the crabs that burrow into the sides of the rice paddies eventually causing them to lose integrity, leading to collapses of entire paddy systems.

Without the water buffalo wallows, villagers no longer had a place to soak the palm fronds they needed to thatch their roofs, leading them to rely on locally made clay roof tiles, which caused massive deforestation as trees were cut down to fuel the tile kilns.

And with no pest control since the birds were gone (no forests) the snakes and lizards and fish were gone (no wallows) malaria spread like wildfire. Even farms that used chemicals found that mosquitoes quickly became resistant no matter how much they upped the dosage every year.

All over the world, when a system that has evolved for long periods of time is radically changed or altered, we find the same examples of disaster and collapse. Here's Charles Marohn discussing the subject in the book Strong Towns:

The flip side on "inappropriate technology" is the famous parable of "Chesterton's Fence": if you come across a gate in a field and see no reason why its should be there, do not remove it until you have figured out why it was put there in the first place.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/805923727632281601?s=20

Millennia of hard earned handed down tradition and agricultural and ecological knowledge is being lost year after year, every time an old farmer dies without heirs. In many cases we have passed the point of no return: we will have to argue in the dark.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/837870075298230272?s=20

Most of this thread have so far been inspired by the great work of Dr. Ranil Senanayake and G.K. Chesterton. What follows will be more observations on tradition and culture and how it intersects with ecology and sustainability, but from other thinkers/authors.

A more recent example from Akita prefecture in Japan, where dwarf apple trees were introduced to orchards. The owls could not perch or nest in these trees so before anyone understood it rodent populations exploded. english.agrinews.co.jp/?p=4636

How Sri Lankan religious festivals and customs are timed to function as pest control: 1. The torches carried by villagers as they go to and from temples after dark destroy huge numbers of insects just when these are at their peak breeding time and most destructive to agriculture.

2. Conch shells and drums inscribed with religious symbols and rhythmic chanting serves well to create booming noises carrying over large areas. There is a theory that these booms disrupt insect mating calls, leading to fewer insects as the festivals are timed to peak breeding.

3. Related, the water power automatic bamboo pipe drums developed by all rice growing cultures which serves to deter rats and also to disrupt insect mating calls. Sri Lanka has these too, in Japan they are called "shishi odoshi", deer scarers.

4. Summer offerings. In all Sri Lankan religions there are ceremonies where flowers, lights and fruits are offered. These attract insects, which are destroyed by the flames of the lights or eaten by the birds attracted by the fruits. The flowers perpetuate the tradition: beauty.

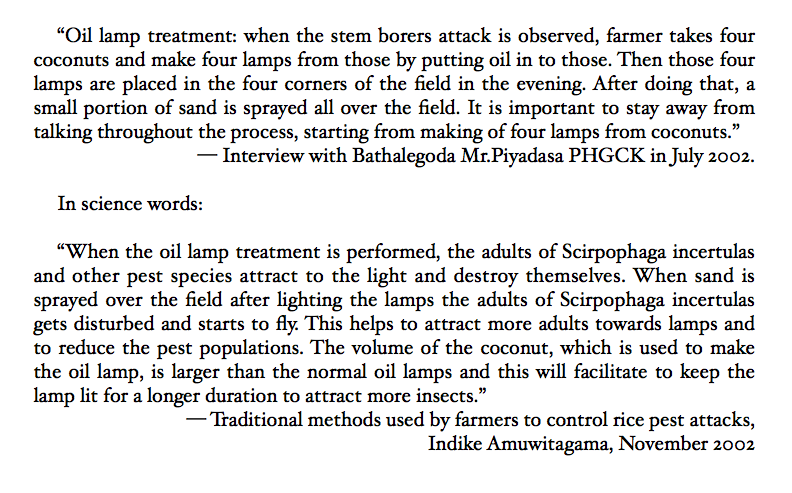

5. Oil lamps. Because some people think I am making this up: first we have the farmer's own words, describing the ritual, then a modern scientific explanation of how the ritual works as a mechanical pesticide. The oil is a home grown, home pressed, seed oil, of course.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh