The naval shipworm Teredo Navalis is an under-appreciated marker of globalization.

It's a type of highly adapted clam that bores into waterlogged wood using the remnants of its shell as a rasping saw:

It's a type of highly adapted clam that bores into waterlogged wood using the remnants of its shell as a rasping saw:

No one is really sure where in the world it originated, but it seems clear it's an early example of a marine invasive species.

Its marine wood diet suggests that it evolved among mangroves, but we first find written references in ancient Greece where mangroves were absent:

Its marine wood diet suggests that it evolved among mangroves, but we first find written references in ancient Greece where mangroves were absent:

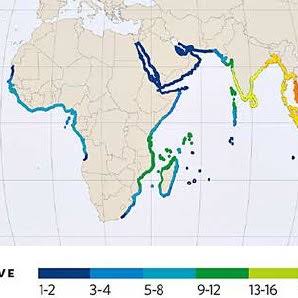

References in Greek texts from the 4th century BC are IMO suggestive of early voyages to the coast of West Africa, the nearest navigable mangrove forests (unless shipworm managed to somehow get carried across the Sinai isthmus):

academia.edu/34223273/Effec…

academia.edu/34223273/Effec…

Shipworm have bacteria living in their gills that allow them to digest cellulose. This makes them astonishingly efficient at turning submerged wood into sawdust. Unprotected timber in shipworm-infested waters can completely disintegrate in eight or ten years.

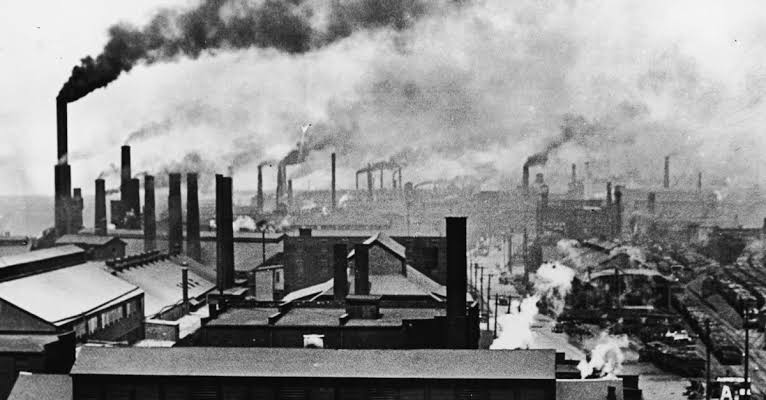

This becomes a really big problem with the Age of Sail. Ships plying the oceans are eaten from the inside out as they travel.

You also end up with external fouling from goose barnacles and other organisms.

You also end up with external fouling from goose barnacles and other organisms.

This slows wooden ships down drastically and eventually destroys them.

Shipyards came up with various ways to solve the problem. Some boats had double hulls, with a cheap wooden outer surface that could be periodically replaced in dry dock.

Shipyards came up with various ways to solve the problem. Some boats had double hulls, with a cheap wooden outer surface that could be periodically replaced in dry dock.

Tar paint was also used, and lead or copper plates were bolted on to the keel from relatively early times.

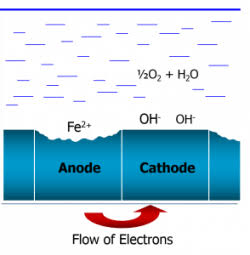

The metal solution was probably most effective, but it had a problematic side-effect: it turned the ship into a giant battery.

The metal solution was probably most effective, but it had a problematic side-effect: it turned the ship into a giant battery.

With seawater acting as an electrolyte, the copper or lead sheathing would become the positive cathode and the iron bolts holding the ship together become the negative anode.

Anodes quickly turn to rust, so again your ship is destroyed.

Anodes quickly turn to rust, so again your ship is destroyed.

BUT copper sheathing was so effective at preventing shipworm that from the mid-18th century the British navy decided it was better to replace the iron bolts (and update them with more corrosion-resistant alloys) than to replace all the timber instead.

The American Revolution provided the real spur to this. Copper is a relatively expensive metal. But with the British Navy fighting a trans-oceanic war, fouling and shipworm was a national security problem that had to be fixed, so the entire fleet was coppered in short order.

That required a LOT of copper. Luckily for the British, there were large domestic deposits.

Cornwall and Devon had been mined since classical times as one of the ancient world's most important sources of tin, which was alloyed with copper to make bronze.

Cornwall and Devon had been mined since classical times as one of the ancient world's most important sources of tin, which was alloyed with copper to make bronze.

Below the surface tin deposits, there were extensive reserves of copper itself, but they were hard to reach. Most were so deep underground that they were below the water table, so the pits would flood.

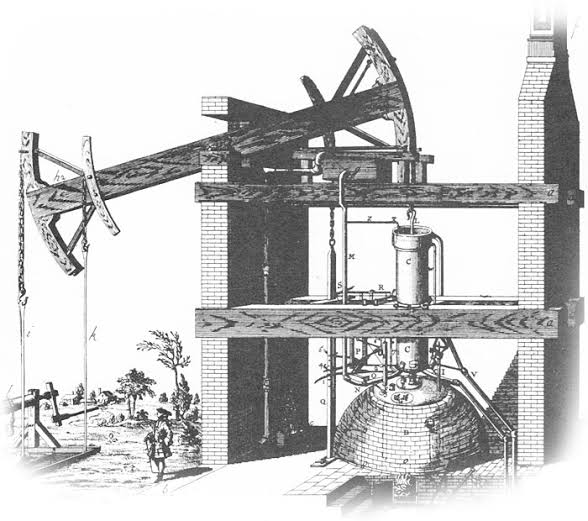

Early in the century a Baptist preacher from Devon called Thomas Newcomen invented a steam pump that could drain mines, but it was pretty inefficient. It got used in Britain's coal mines because fuel in coal regions was abundant and cheap.

But Devon and Cornwall had no coalfields of their own so had to rely on expensive imported fuel, so the copper ore was still inaccessible.

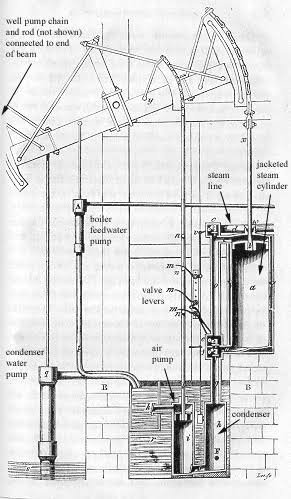

The breakthrough was James Watt's steam engine.

The breakthrough was James Watt's steam engine.

By adding a (copper) condenser, Watt massively improved the efficiency of the Newcomen engine and made it economical to drain deep mines to access Devon and Cornwall's copper reserves.

Boulton & Watt, James Watt's company, was initially entirely focused on the mining industry.

The business model was for Boulton & Watt to provide the engine for free while the mine owner paid them fees based on the tonnage of coal saved.

The business model was for Boulton & Watt to provide the engine for free while the mine owner paid them fees based on the tonnage of coal saved.

Of course Watt's engine was so efficient that it was able to provide power in a host of unexpected ways, to the extent that mining engineering rapidly became a relatively minor use of steam power.

There's plenty of causes of the Industrial Revolution, but I think for all the talk of coal and iron the role of copper has been under-appreciated. It wasn't a high-value industry but it was nonetheless essential.

There's a whole other thread to be written about the contemporaneous story of copper and the slave trade.

I might write about that later, but right now I'm on holiday so I'm off to the beach.

I might write about that later, but right now I'm on holiday so I'm off to the beach.

OK I'm back!

Just to show how close these dates were:

1769: Watt gets his steam engine patent, but doesn't successfully commercialize it

1775: American War of Independence starts; Watt teams up with the manufacturer Matthew Boulton

1779-1781: Entire Royal Navy is coppered.

Just to show how close these dates were:

1769: Watt gets his steam engine patent, but doesn't successfully commercialize it

1775: American War of Independence starts; Watt teams up with the manufacturer Matthew Boulton

1779-1781: Entire Royal Navy is coppered.

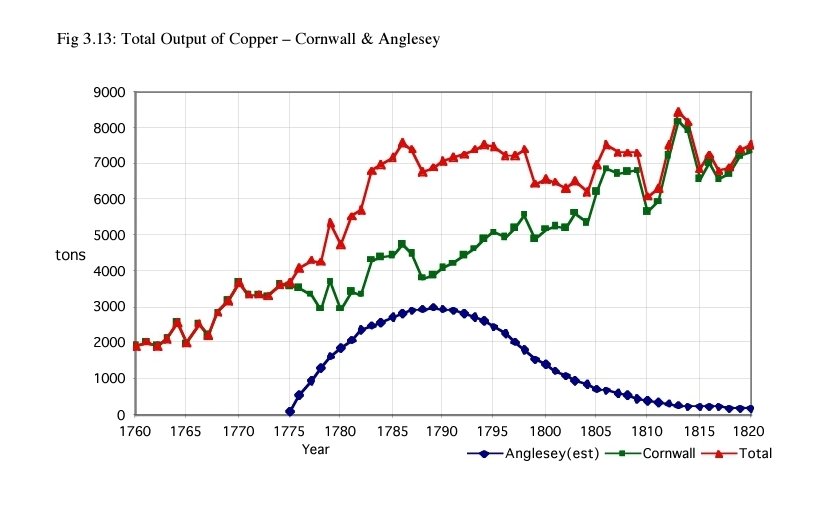

This study shows how rapidly Cornish copper production ramped up in this period.

For the UK as a whole, output doubles in 10 years:

google.com/url?sa=t&sourc…

For the UK as a whole, output doubles in 10 years:

google.com/url?sa=t&sourc…

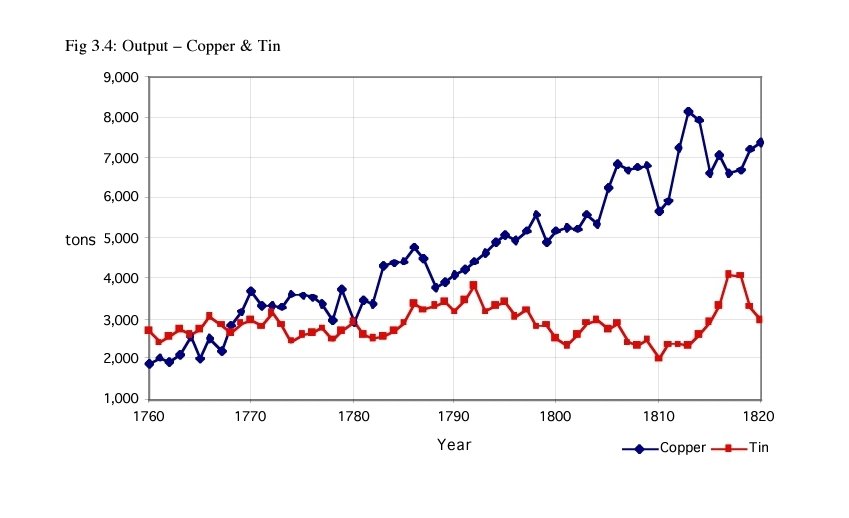

People associate Cornish mining with tin, but at least in this period copper becomes a much bigger trade in volume terms:

And there is an interesting example of an early commodity boom and bust in this era. You might have thought that booming copper demand would be good for Cornish copper miners, but in fact it provokes a crisis that was depicted in the TV series Poldark.

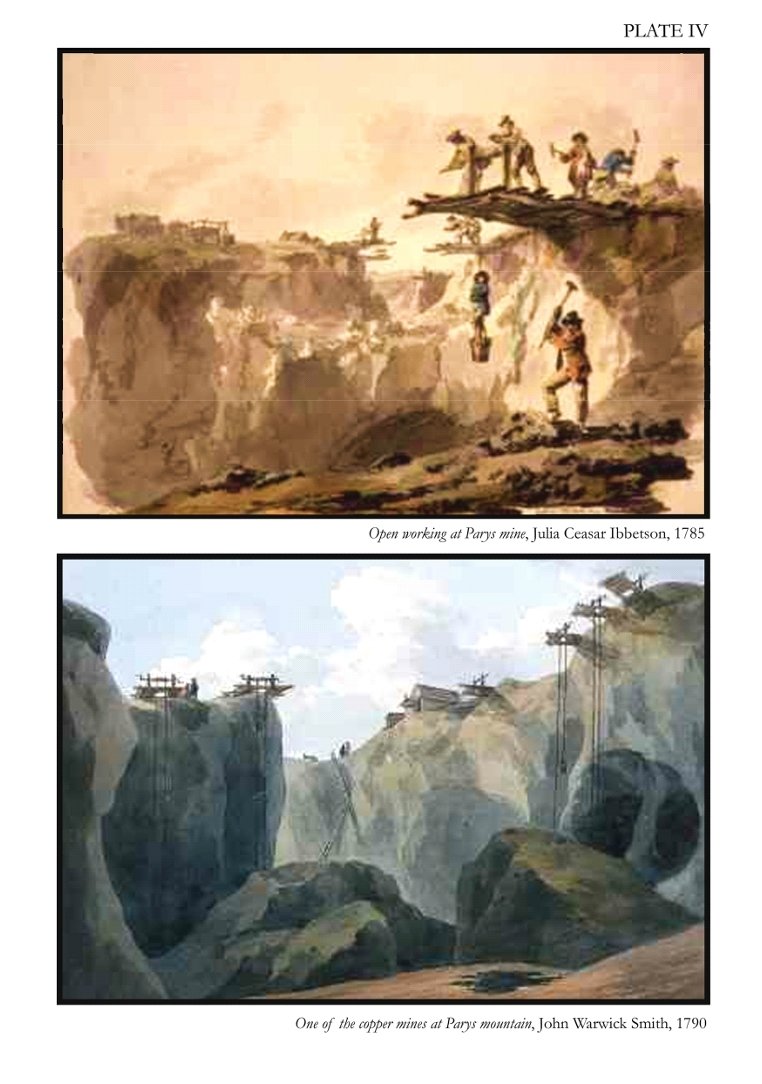

In Anglesey in north Wales there's a rich copper deposit on the boundary of two landowners who've spent years in court arguing about it.

Rising prices encourage them to settle their differences and exploit the resource.

Rising prices encourage them to settle their differences and exploit the resource.

The Parys mountain copper is near the surface and can be mined in a huge open pit that still exists today.

It produces so much metal that copper prices collapse again and the Cornish miners are pushed to the brink.

It produces so much metal that copper prices collapse again and the Cornish miners are pushed to the brink.

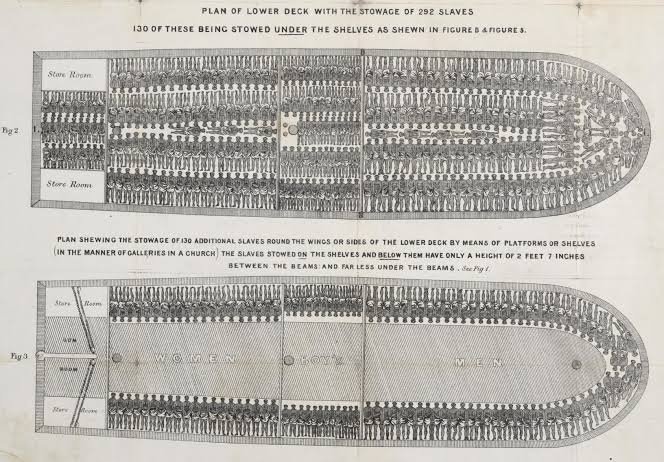

So by 1781 the Royal Navy has coppered all of its ships, but output is still rising. Where is it all going? The slave trade.

Slave ships were the next major part of the British fleet to add copper sheathing after the military.

Coppered ships could complete the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas about one-sixth quicker than ordinary ones.

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Coppered ships could complete the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas about one-sixth quicker than ordinary ones.

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

That significantly reduced the horrendous death rates onboard ship. Slave traders cared about this not because of any sense of humanity but because it improved their profit margins.

Copper sheathing could pay for itself in a single voyage, so that by about 1790 the entire slave fleet had been coppered.

That wasn't the only use of copper in the slavers' Triangular Trade between Britain, Africa and the Americas.

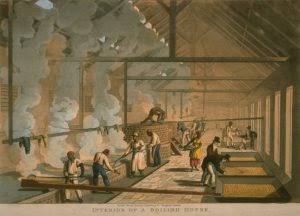

On the sugar plantations of the Caribbean, cane juice was reduced to molasses in copper boilers that were favoured for the metal's conductive properties.

On the sugar plantations of the Caribbean, cane juice was reduced to molasses in copper boilers that were favoured for the metal's conductive properties.

The molasses and muscovado were shipped back to the slave port of Bristol, which was at the time where most of the world's refined white sugar was produced.

Those mass-produced calories also aided the Industrial Revolution, by providing cheap nourishment for the urban workforce.

Those mass-produced calories also aided the Industrial Revolution, by providing cheap nourishment for the urban workforce.

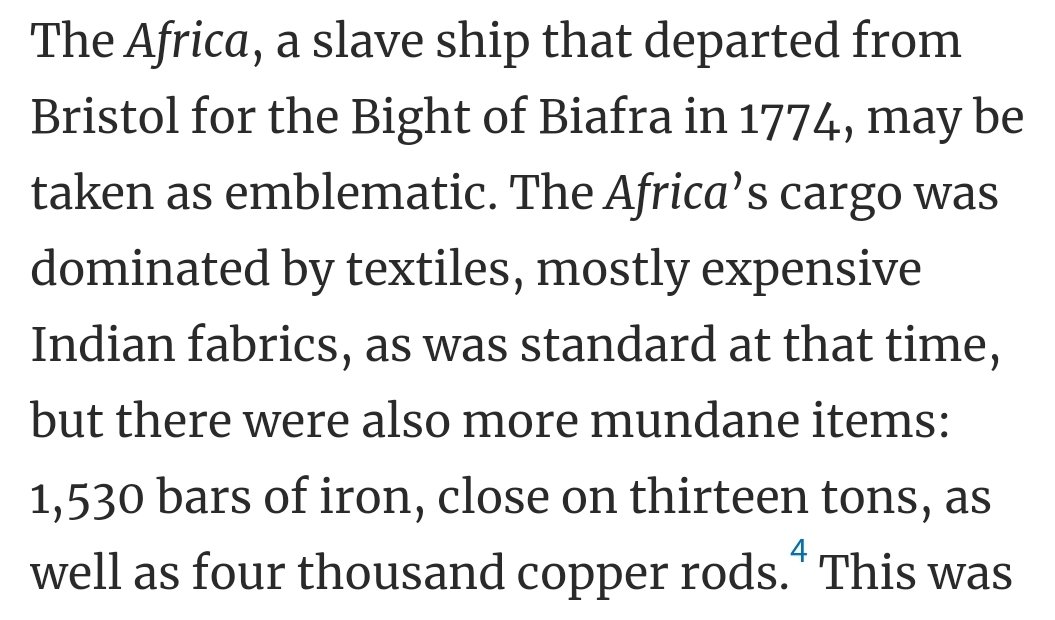

And copper was also crucial to the third apex of the Triangular Trade, in Africa.

Copper or bronze bracelets known as manillas had for hundreds of years been the main form of currency in West Africa.

Copper or bronze bracelets known as manillas had for hundreds of years been the main form of currency in West Africa.

African metallurgy was very sophisticated — just look at the looted Benin Bronzes in European museums — but West Africa didn't have any significant copper deposits, so it needed to import the metal.

Mostly people focus on the luxury goods like fabrics and porcelain that slave traders used to pay for captured slaves — but copper and iron was a significant slice of commerce, too:

academic.oup.com/past/article/2…

academic.oup.com/past/article/2…

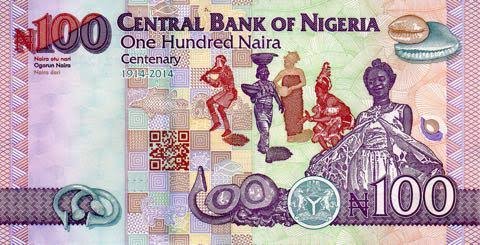

Manillas were used in Nigeria well into the 20th century, and in spite of their association as the unofficial currency of the slave trade you still see them cropping up on banknotes today:

(ends)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh