Carson Block of @muddywatersre writing in the FT lays the blame of stonk gyrations like GameStop (sub $20 on 12 Jan, up 18-fold in 10 trading days) squarely on low rates and passive investing.

This is Hogwash, Blatherskite, Buncombe, and Taradiddle.

ft.com/content/dbfc69…

This is Hogwash, Blatherskite, Buncombe, and Taradiddle.

ft.com/content/dbfc69…

Pure Trumpery.

It was 1 stock out of tens of thousands in the world which moved that way and has become a meme unto itself of fantabulous stock and social movement.

Carson talks briefly about low rates and government bailouts, which theoretically should affect the others.

It was 1 stock out of tens of thousands in the world which moved that way and has become a meme unto itself of fantabulous stock and social movement.

Carson talks briefly about low rates and government bailouts, which theoretically should affect the others.

But then he falls into the trap that many others who do not understand passive investing do.

This is NOT how passive investing works.

This is NOT how passive investing works.

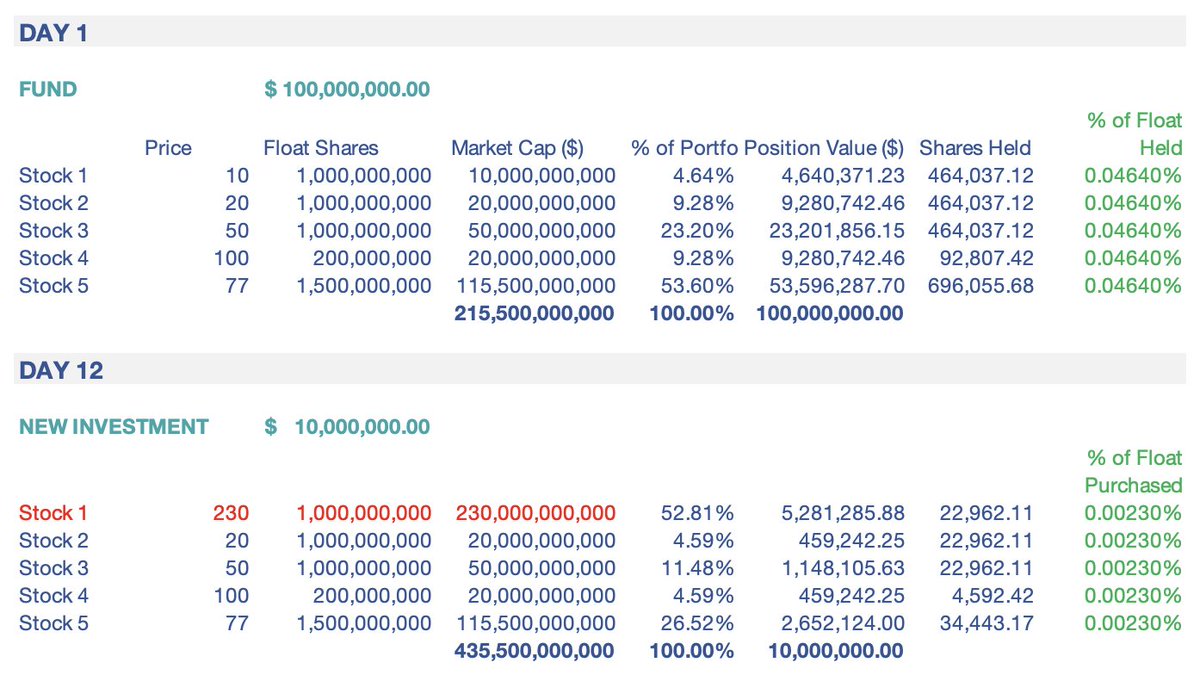

To be clear: if a passive fund owns $1bn of stock of an index which has a Sum (Stock Float Shares x Price) of $1trn, that fund will own 1/1000 of the float shares of each stock.

If the price of 1 stock rises 23-fold in 11 days, passive investors will do...

exactly nothing.

If the price of 1 stock rises 23-fold in 11 days, passive investors will do...

exactly nothing.

If the rise in that 1 stock leads to the index float market cap moving to $1.02trln, then if the fund receives an extra $100mm, it will go buy exactly $100mm/1.02trln of the float of each stock in the index (i.e. just under 1bp - of EACH stock - Apple, AMZN, and GME).

He then pays homage to the work done by Michael Green of Logica Funds, which is indeed quite important in explaining the over-arching issues of the impact of passive fund flows on markets, but he adds this point, which is of dubious value.

Yes passive funds "have to buy more" the same way that if the price of a meal at your favorite restaurant goes up, you have to spend more $ for it (duh). But if you still go the same number of times per year, it does not change what percentage of their annual covers you consume.

The price you pay goes up, but there is zero incremental squeeze. Your 1x/quarter is still 1x/quarter.

The way that works for passive flows for most major indices around the world is as below:

The way that works for passive flows for most major indices around the world is as below:

Stocks of differing prices and float shares outstanding combine to make up a total, and you own a percentage of the total, therefore you own the same percentage of float of each stock as in the green section on the right.

IF Stock 1 rises 23-fold in 11 days the weight of that stock in the index is highly likely to go up, and let's say there are $10mm of new inflows. More of the $10mm will go to Stock 1 (the same way more of your disposable income might go to your favorite restaurant for 1 meal/yr)

but in the grand scheme of things, you will still buy the same percent of float of Stock 1 as you will of other stocks.

If you go to the restaurant once a year, you will not consume more of their capacity (float) compared to other restaurants just because they raised prices.

If you go to the restaurant once a year, you will not consume more of their capacity (float) compared to other restaurants just because they raised prices.

You will buy the same portion of float of Stock 1 as you buy of all the other stocks when incremental flow comes in.

And if Stock 1 rises 23-fold and no inflows come in, the portfolio weight increases...

BUT THERE IS NO ADDITIONAL BUYING JUST BECAUSE IT WENT UP.

And if Stock 1 rises 23-fold and no inflows come in, the portfolio weight increases...

BUT THERE IS NO ADDITIONAL BUYING JUST BECAUSE IT WENT UP.

There are a few more problems.

I can assure Carson that lower contributions to 401Ks does not mean passive funds have to sell. That's not the way the arithmetic works.

To be sure, if there is a giant macro hit to the economy, some people may sell stocks, ETFs, funds, etc

I can assure Carson that lower contributions to 401Ks does not mean passive funds have to sell. That's not the way the arithmetic works.

To be sure, if there is a giant macro hit to the economy, some people may sell stocks, ETFs, funds, etc

but that has not been different than prior macro risk-off situations. Markets go up and markets go down.

His penultimate paragraph is odd.

Yes, one should not ignore societal impacts of bubbles. But the rest of the first para there does not necessarily follow.

His penultimate paragraph is odd.

Yes, one should not ignore societal impacts of bubbles. But the rest of the first para there does not necessarily follow.

Passive funds introduce distortions, but if the three major players became 300 with the same assets because fund size was capped by law, that would... mean nothing?

As to "markets' contributions to instability" it is not clear to what instability markets contribute. Their own?

As to "markets' contributions to instability" it is not clear to what instability markets contribute. Their own?

As to the impact of rates on all this... I can pretty much guarantee that the fact of near-zero rates did not CAUSE Gamestop to rise 23-fold in 11 trading days.

One could argue that the far-outlying events become more dramatic under zero-interest rate environments, but we have

One could argue that the far-outlying events become more dramatic under zero-interest rate environments, but we have

a very small sample set and who is to say if rates were 2% we would not be seeing the same events. Prove it.

I get the urge to use a widely observed phenomenon to raise one's voice.

I get the urge to use a widely observed phenomenon to raise one's voice.

If it's rates, talk about broader impact.

If passive is the problem, do it right.

If markets are too rich, say so, but all the factors noted existed before GME went above $20 less than 1mo ago.

If less expert policymakers need expert input, it needs to be better than that.

If passive is the problem, do it right.

If markets are too rich, say so, but all the factors noted existed before GME went above $20 less than 1mo ago.

If less expert policymakers need expert input, it needs to be better than that.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh