Just following on from that discussion of Zack Snyder’s “Justice League”, some thoughts that were too nerdy and esoteric for the article.

In terms of positioning “Justice League” as a reconstruction, it’s obvious even looking at the comics from which it draws.

In terms of positioning “Justice League” as a reconstruction, it’s obvious even looking at the comics from which it draws.

“Batman v. Superman” drew very heavily from two of the biggest “dark age of comics” stories, and hinted at a third.

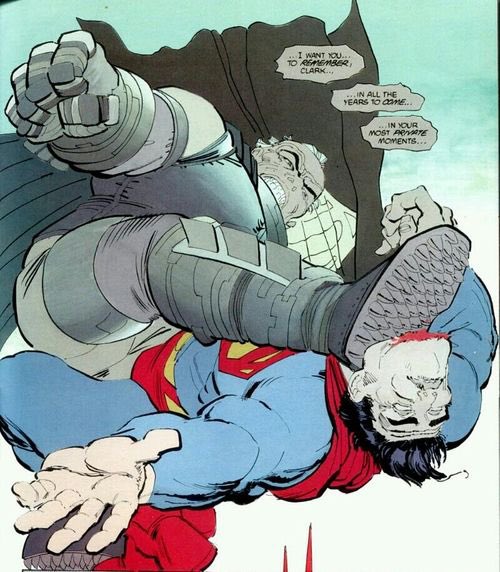

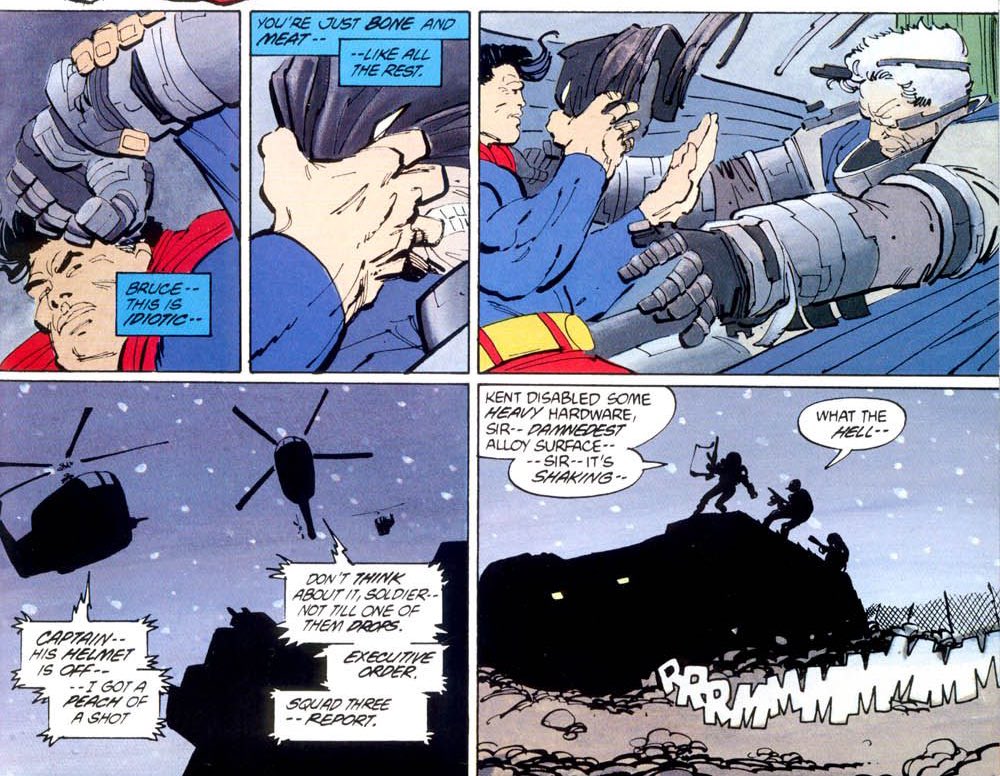

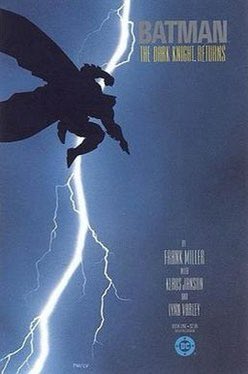

A lot of the Old Batman Versus Institutionally Challenged Superman stuff comes from Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns”, which ushered in “the dark age.”

A lot of the Old Batman Versus Institutionally Challenged Superman stuff comes from Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns”, which ushered in “the dark age.”

The climax of the film is lifted directly from the mid-nineties event “The Death of Superman”, which involved - you guessed it - the death of Superman and the introduction of Doomsday.

It was the peak of the nineties “darker and edgier” era, and the height of comics speculation.

It was the peak of the nineties “darker and edgier” era, and the height of comics speculation.

There’s a solid argument that “The Death of Superman”, in helping codify these sorts of big events and pandering so cravenly to speculators, almost killed the superhero comic.

Plus, you know, killing Superman.

Plus, you know, killing Superman.

Many fans of the genre consider the nineties a nadir for superheroes. It was a wilderness. There were some great books, but the genre kinda lost its way.

This makes it interesting and pointed that “Batman v. Superman” draws so heavily from it, even carrying over the grimness.

This makes it interesting and pointed that “Batman v. Superman” draws so heavily from it, even carrying over the grimness.

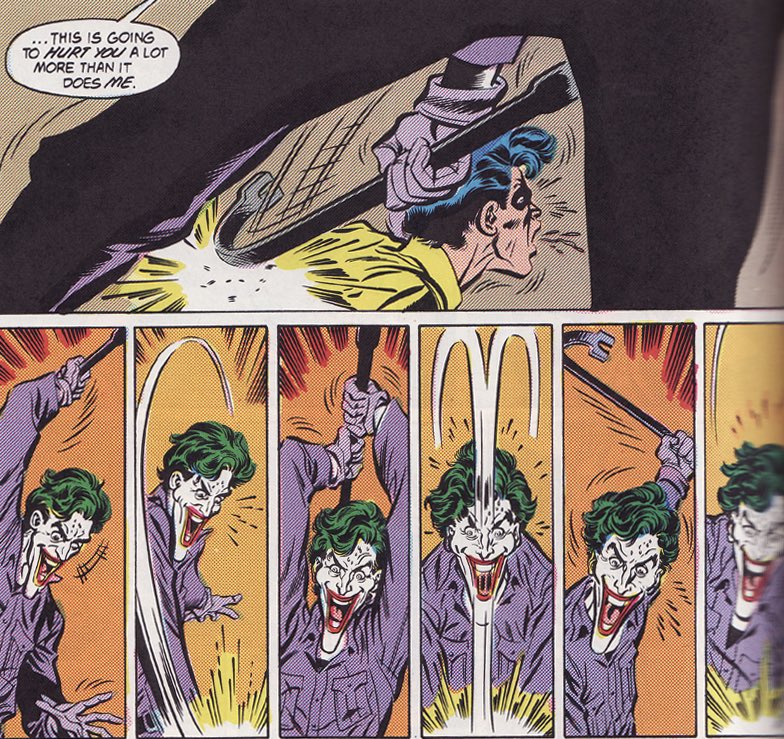

Incidentally, the third big story to which “Batman v. Superman” alludes is “A Death in the Family.”

Inspired by an inference in “The Dark Knight Returns”, DC asked fans to vote on whether Robin would get beaten to death by the Joker.

No surprises which way fans voted.

Inspired by an inference in “The Dark Knight Returns”, DC asked fans to vote on whether Robin would get beaten to death by the Joker.

No surprises which way fans voted.

Part of what’s interesting about this “darker and edgier” trend is the extent to which fans are implicated and complicit in it.

They bought those polybagged collectors’ issues. They voted for the Boy Wonder to die, brutally.

On some level, they wanted it.

They bought those polybagged collectors’ issues. They voted for the Boy Wonder to die, brutally.

On some level, they wanted it.

So “Batman v. Superman” draws from those comics, and pushes the audience’s discomfort further.

It’s a version of “The Dark Knight Returns” where the audience is aggressively asked why they’re rooting for Batman - why they wanted this.

And then accepting it’s not sustainable.

It’s a version of “The Dark Knight Returns” where the audience is aggressively asked why they’re rooting for Batman - why they wanted this.

And then accepting it’s not sustainable.

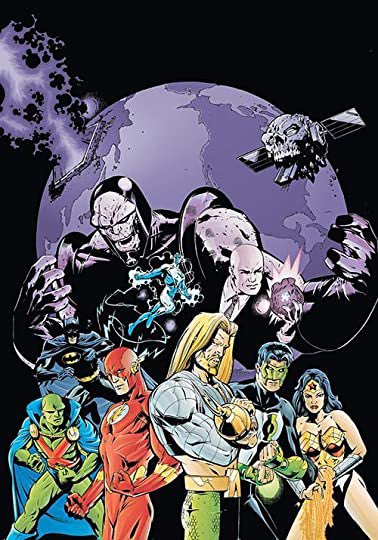

Which is why it’s interesting that a major influence on “Justice League” is none other than... Grant Morrison.

Morrison took over “Justice League” after the “Death of Superman”, and immediately began a process of reconstruction and repair after a decade of grim turbulence.

Morrison took over “Justice League” after the “Death of Superman”, and immediately began a process of reconstruction and repair after a decade of grim turbulence.

Interestingly, Morrison was a big influence on the Snyder films from the start. Jor-El’s big inspirational “this is what Superman should be” speech in “Man of Steel”?

It draws quite heavily from Morrison and Quitely’s “All-Star Superman.”

It draws quite heavily from Morrison and Quitely’s “All-Star Superman.”

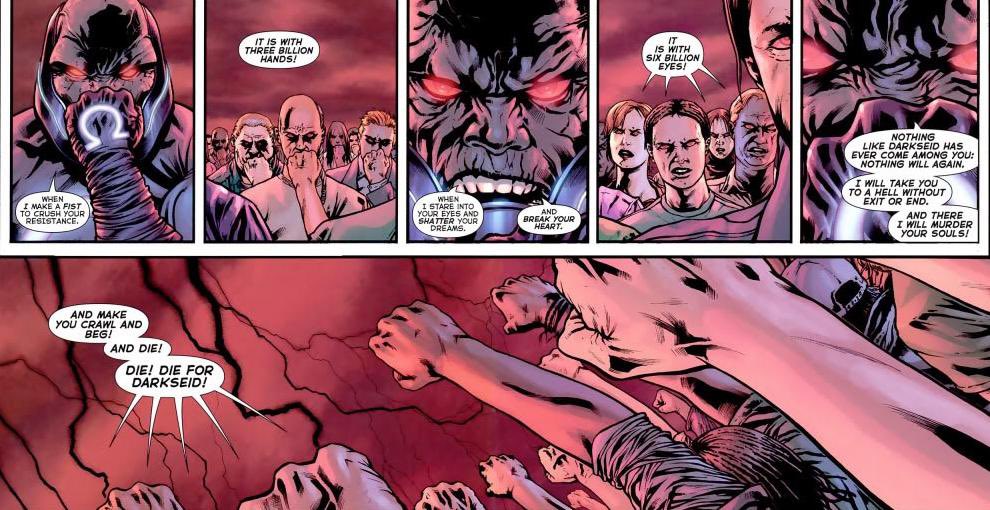

The biggest influence of Morrison on “Justice League” is the treatment of Darkseid and the New Gods.

In particular, Morrison has had Darkseid invade Earth twice. Once in the second arc of their “Justice League” run and then again in “Final Crisis.”

In particular, Morrison has had Darkseid invade Earth twice. Once in the second arc of their “Justice League” run and then again in “Final Crisis.”

Indeed, the idea of a dark future where Darkseid has already conquered the planet and the only heroes left are a rag-tag bunch of scrappy underdogs?

That’s Morrison and Porter’s “Rock of Ages”, which feels like a dry run for “Final Crisis.”

That’s Morrison and Porter’s “Rock of Ages”, which feels like a dry run for “Final Crisis.”

Interestingly, this influence is borne out in the rumours of Snyder’s plans for the “Justice League” sequel, in which Lex Luthor would assemble an “Injustice Gang” to defeat the team and lead to a dark future in which Darkseid conquers Earth.

That’s basically “Rock of Ages.”

That’s basically “Rock of Ages.”

Anyway, my inner comic book geek, who I don’t feed as much as I should, kinda loves that there’s there’s an expansive nine-and-a-half-hour big screen superhero saga that journeys from Frank Miller’s deconstruction to Grant Morrison’s reconstruction of the classic DC superheroes.

This observation was all a bit too “inside baseball” for an already quite long article on the interesting journey through deconstruction to reconstruction, from “Man of Steel” through to “Justice League.”

escapistmagazine.com/v2/man-of-stee…

escapistmagazine.com/v2/man-of-stee…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh