1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand the connections between "earnings growth" and "return on capital".

This will help you analyze businesses better, and thus become a better investor.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand the connections between "earnings growth" and "return on capital".

This will help you analyze businesses better, and thus become a better investor.

2/

Imagine we have 2 businesses, S and F.

S is a Slow Growth business. Its earnings grow at 6% per year.

F is a (relatively) Fast Growth business. Its earnings grow at 9% per year.

Both businesses are trading at 15 times earnings.

Which is the better investment?

Imagine we have 2 businesses, S and F.

S is a Slow Growth business. Its earnings grow at 6% per year.

F is a (relatively) Fast Growth business. Its earnings grow at 9% per year.

Both businesses are trading at 15 times earnings.

Which is the better investment?

3/

We may be tempted to answer that F is the better investment.

After all, both S and F are trading at the same price (15 times earnings).

But with F, we get 9% growth -- compared to just 6% for S.

Sounds like a no-brainer.

We may be tempted to answer that F is the better investment.

After all, both S and F are trading at the same price (15 times earnings).

But with F, we get 9% growth -- compared to just 6% for S.

Sounds like a no-brainer.

4/

But this logic is incorrect.

The reason is: it's not enough to *just* look at earnings growth.

We should also look at how much *capital* is required by the business to produce this earnings growth.

But this logic is incorrect.

The reason is: it's not enough to *just* look at earnings growth.

We should also look at how much *capital* is required by the business to produce this earnings growth.

5/

As Warren Buffett is fond of saying, even a totally dormant savings account will earn more in interest as time passes -- simply because it keeps adding to its base of capital (ie, interest earned each year is kept in the account, and not distributed to the account holder).

As Warren Buffett is fond of saying, even a totally dormant savings account will earn more in interest as time passes -- simply because it keeps adding to its base of capital (ie, interest earned each year is kept in the account, and not distributed to the account holder).

6/

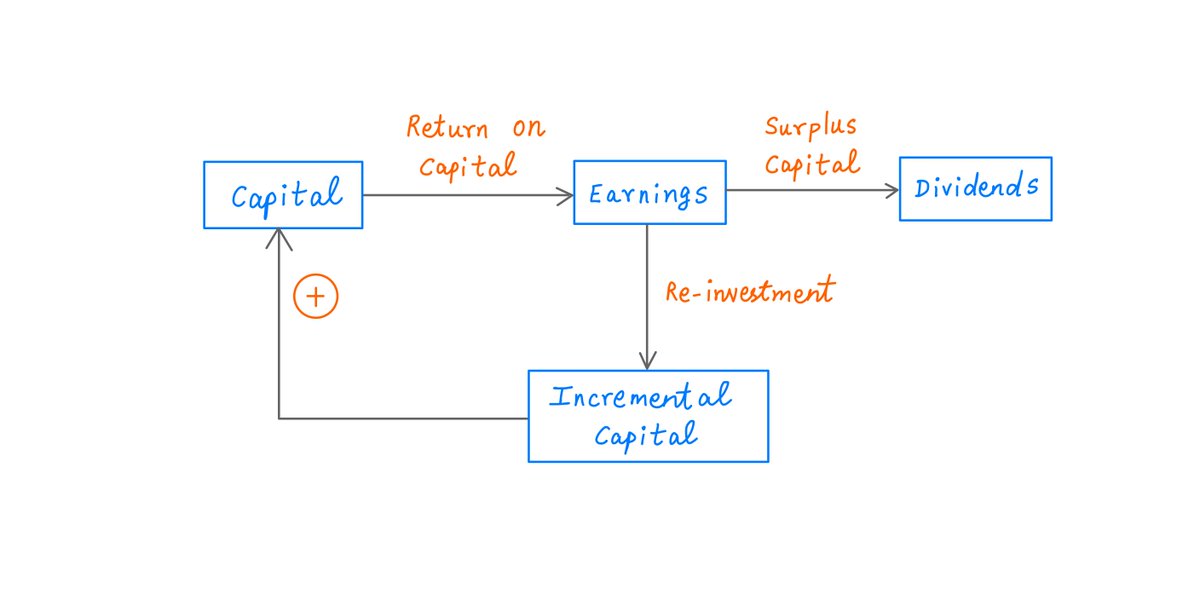

In the same way, businesses that retain part of their earnings (instead of distributing it all to owners as dividends) keep adding to their base of capital.

And all this additional capital naturally produces additional earnings.

In the same way, businesses that retain part of their earnings (instead of distributing it all to owners as dividends) keep adding to their base of capital.

And all this additional capital naturally produces additional earnings.

7/

So, the key question is: *how much* additional capital is needed to produce $1 of additional earnings?

For example, suppose our Slow Growth business (S) returns 90% of its earnings as dividends each year. It retains the other 10%, which produces 6% earnings growth.

So, the key question is: *how much* additional capital is needed to produce $1 of additional earnings?

For example, suppose our Slow Growth business (S) returns 90% of its earnings as dividends each year. It retains the other 10%, which produces 6% earnings growth.

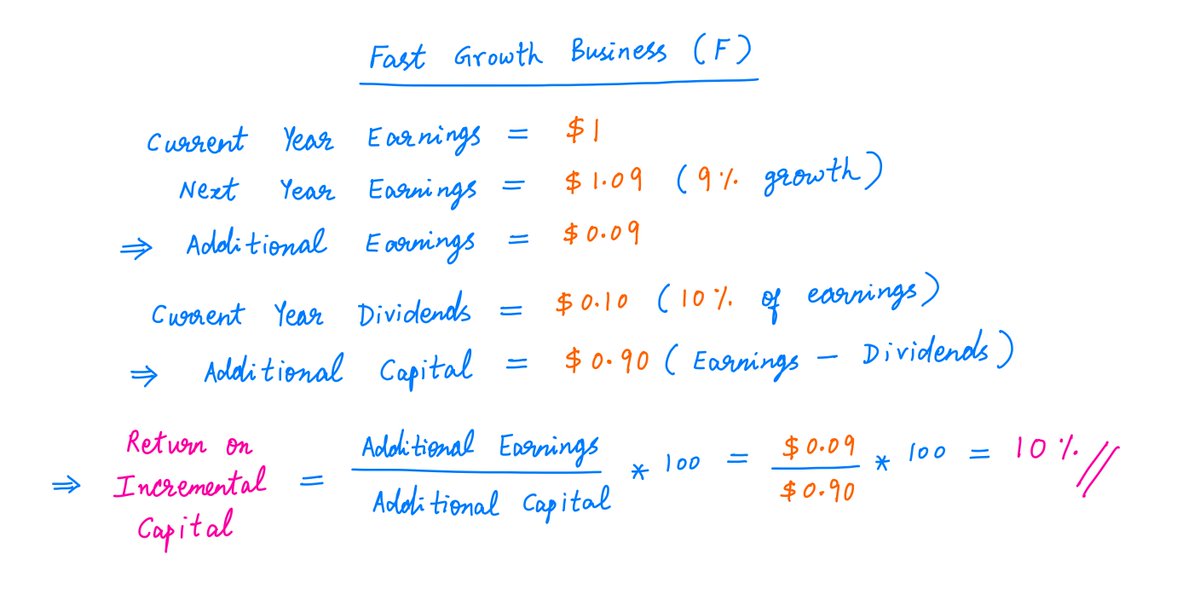

9/

By contrast, suppose our Fast Growth business (F) retains 90% of its earnings each year, and dividends out only the other 10%.

This is just a 10% return on incremental capital -- much worse than S's 60%.

By contrast, suppose our Fast Growth business (F) retains 90% of its earnings each year, and dividends out only the other 10%.

This is just a 10% return on incremental capital -- much worse than S's 60%.

10/

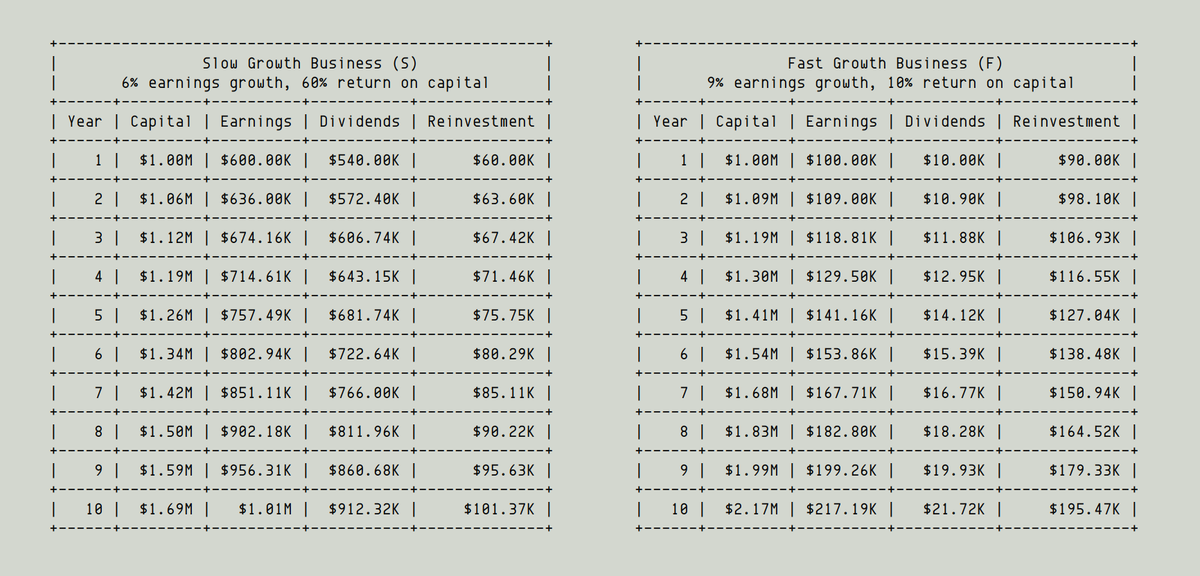

Here's a side-by-side 10-year simulation of both S and F.

We start them both off with $1M in capital.

For every $1 of earnings, S pays out $0.90 as dividends (vs $0.10 for F).

But F's dividends *grow* at 9% per year (vs 6% for S).

Here's a side-by-side 10-year simulation of both S and F.

We start them both off with $1M in capital.

For every $1 of earnings, S pays out $0.90 as dividends (vs $0.10 for F).

But F's dividends *grow* at 9% per year (vs 6% for S).

11/

Let's think about these businesses from the standpoint of Andy -- a "buy and hold forever" shareholder.

Andy's cash *outflow* is the 15x earnings he pays to buy these businesses.

In return, Andy gets a stream of cash *inflows* -- dividends that grow steadily each year.

Let's think about these businesses from the standpoint of Andy -- a "buy and hold forever" shareholder.

Andy's cash *outflow* is the 15x earnings he pays to buy these businesses.

In return, Andy gets a stream of cash *inflows* -- dividends that grow steadily each year.

12/

Andy's annualized return is simply the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of this stream of cash flows.

For more on IRR, please see:

Andy's annualized return is simply the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of this stream of cash flows.

For more on IRR, please see:

https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1284536987861446657

13/

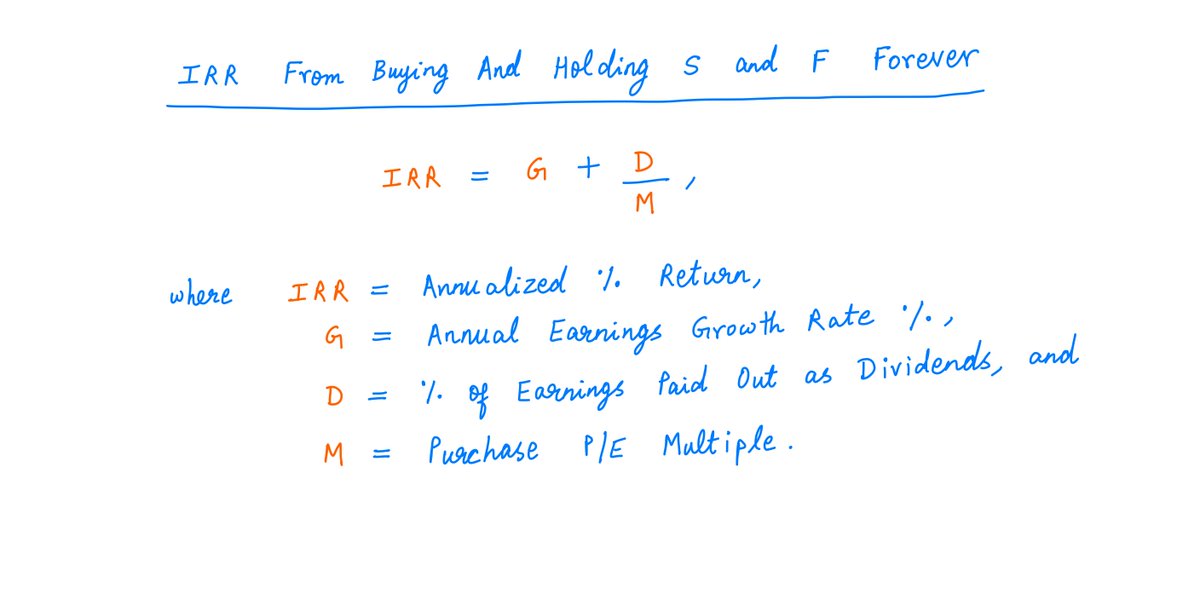

For these particular cash flows, it turns out there's a simple formula for this IRR.

Growth (G) is part of this formula. But so is Dividend Yield (D/M). And if one of these comes at the expense of the other, that can hurt returns.

For these particular cash flows, it turns out there's a simple formula for this IRR.

Growth (G) is part of this formula. But so is Dividend Yield (D/M). And if one of these comes at the expense of the other, that can hurt returns.

14/

Applying the formula, we see that Andy will get a 12% annualized return from buying and holding S (vs ~9.67% for F).

So, in this case, the Slow Growth business actually turns out to be the better long-term investment!

Applying the formula, we see that Andy will get a 12% annualized return from buying and holding S (vs ~9.67% for F).

So, in this case, the Slow Growth business actually turns out to be the better long-term investment!

15/

Key lesson: A business with faster earnings growth isn't necessarily a better investment than a business with slower earnings growth -- even when both trade at the same multiple.

Earnings Growth, Return on Capital, and Dividend/Free Cash Flow Yield -- all play a role.

Key lesson: A business with faster earnings growth isn't necessarily a better investment than a business with slower earnings growth -- even when both trade at the same multiple.

Earnings Growth, Return on Capital, and Dividend/Free Cash Flow Yield -- all play a role.

16/

Thus, when we invest in a business, we need to be confident that it will earn an adequate return on *all* capital.

This includes the capital currently in the business, *plus* all future earnings that will be withheld from us -- and retained in the business.

Thus, when we invest in a business, we need to be confident that it will earn an adequate return on *all* capital.

This includes the capital currently in the business, *plus* all future earnings that will be withheld from us -- and retained in the business.

17/

When thinking about returns earned by a business on retained earnings, we should take into account 2 key factors:

1) Opportunity costs, and

2) Taxes.

When thinking about returns earned by a business on retained earnings, we should take into account 2 key factors:

1) Opportunity costs, and

2) Taxes.

18/

Opportunity costs.

Suppose we know of opportunities that will allow us to earn a 15% return on our money.

Then, we'd likely be better off if our company distributed 100% of its earnings to us, than if it retained a portion and re-invested it at say, only an 8% return.

Opportunity costs.

Suppose we know of opportunities that will allow us to earn a 15% return on our money.

Then, we'd likely be better off if our company distributed 100% of its earnings to us, than if it retained a portion and re-invested it at say, only an 8% return.

19/

Taxes.

Sometimes, our *after-tax* results may be better if the company retains and re-invests earnings for us -- instead of giving us a dividend and forcing us to pay taxes on it before we're allowed to invest the rest.

Taxes.

Sometimes, our *after-tax* results may be better if the company retains and re-invests earnings for us -- instead of giving us a dividend and forcing us to pay taxes on it before we're allowed to invest the rest.

20/

It's also a good idea to be aware of the company's management's compensation structure and incentives that may shape their capital allocation priorities.

For example, managers may be compensated based on "earnings per share" rather than "return on invested capital".

It's also a good idea to be aware of the company's management's compensation structure and incentives that may shape their capital allocation priorities.

For example, managers may be compensated based on "earnings per share" rather than "return on invested capital".

21/

This may create incentives for management to retain and re-invest a big portion of earnings in somewhat low-return projects.

The resulting growth in earnings may boost compensation for managers.

But shareholders may have been better off with a dividend instead.

This may create incentives for management to retain and re-invest a big portion of earnings in somewhat low-return projects.

The resulting growth in earnings may boost compensation for managers.

But shareholders may have been better off with a dividend instead.

22/

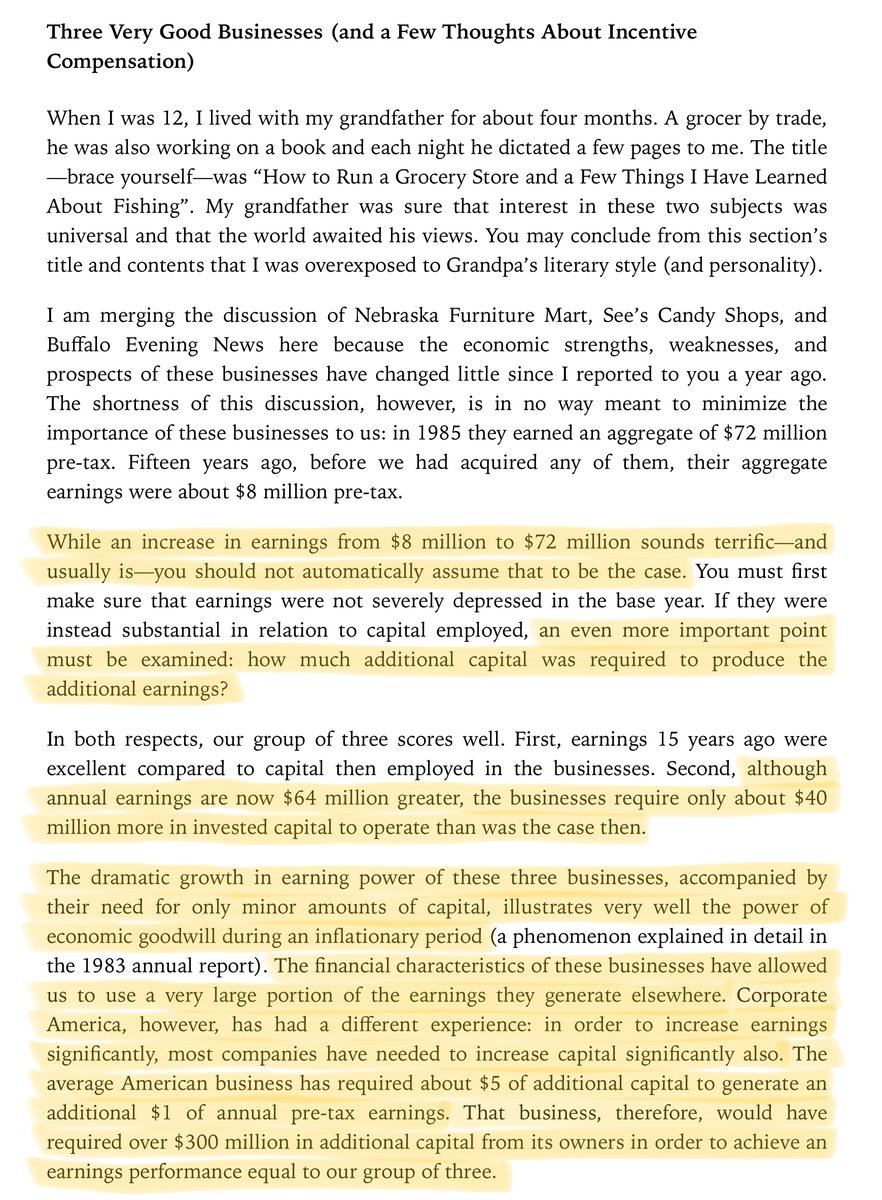

For more on earnings growth, return on capital and incentive compensation, I recommend reading Buffett's 1985 letter: berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1985.h…

For more on earnings growth, return on capital and incentive compensation, I recommend reading Buffett's 1985 letter: berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1985.h…

23/

I also very much like this memo by @HowardMarksBook: You Can't Eat IRR.

Key takeaway: Sometimes, the ability to invest *large* amounts of capital at *decent* returns is more valuable than the ability to invest only *small* amounts of capital, but at *wonderful* returns.

I also very much like this memo by @HowardMarksBook: You Can't Eat IRR.

Key takeaway: Sometimes, the ability to invest *large* amounts of capital at *decent* returns is more valuable than the ability to invest only *small* amounts of capital, but at *wonderful* returns.

24/

@HowardMarksBook was talking about fund managers investing client money.

But I think the idea applies equally well to companies re-investing shareholder capital.

Moderate ROIIC + High re-investment may be better than the other way round.

oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-s…

@HowardMarksBook was talking about fund managers investing client money.

But I think the idea applies equally well to companies re-investing shareholder capital.

Moderate ROIIC + High re-investment may be better than the other way round.

oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-s…

25/

Finally, I recommend watching this very nice ~30 min episode of Focused Compounding.

The "Growth + Free Cash Flow Yield" metric that Andrew and Geoff describe is very similar to the IRR formula I shared above.

(h/t @FocusedCompound)

Finally, I recommend watching this very nice ~30 min episode of Focused Compounding.

The "Growth + Free Cash Flow Yield" metric that Andrew and Geoff describe is very similar to the IRR formula I shared above.

(h/t @FocusedCompound)

26/

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

I hope this thread not only helped you grow your knowledge, but also yielded a decent knowledge return on the time/effort that you spent going through it.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

I hope this thread not only helped you grow your knowledge, but also yielded a decent knowledge return on the time/effort that you spent going through it.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh