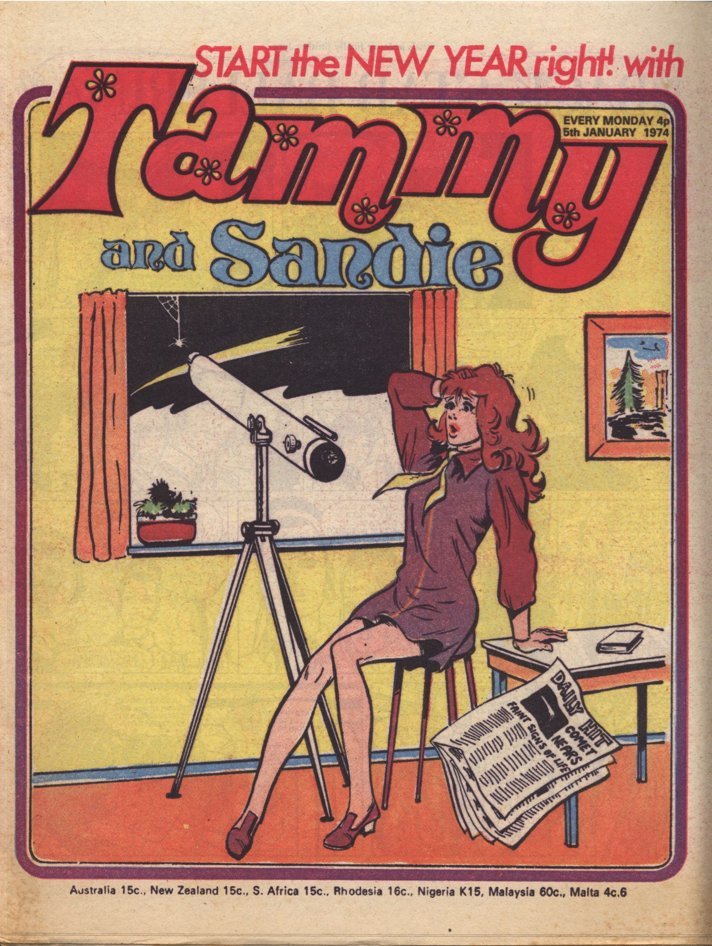

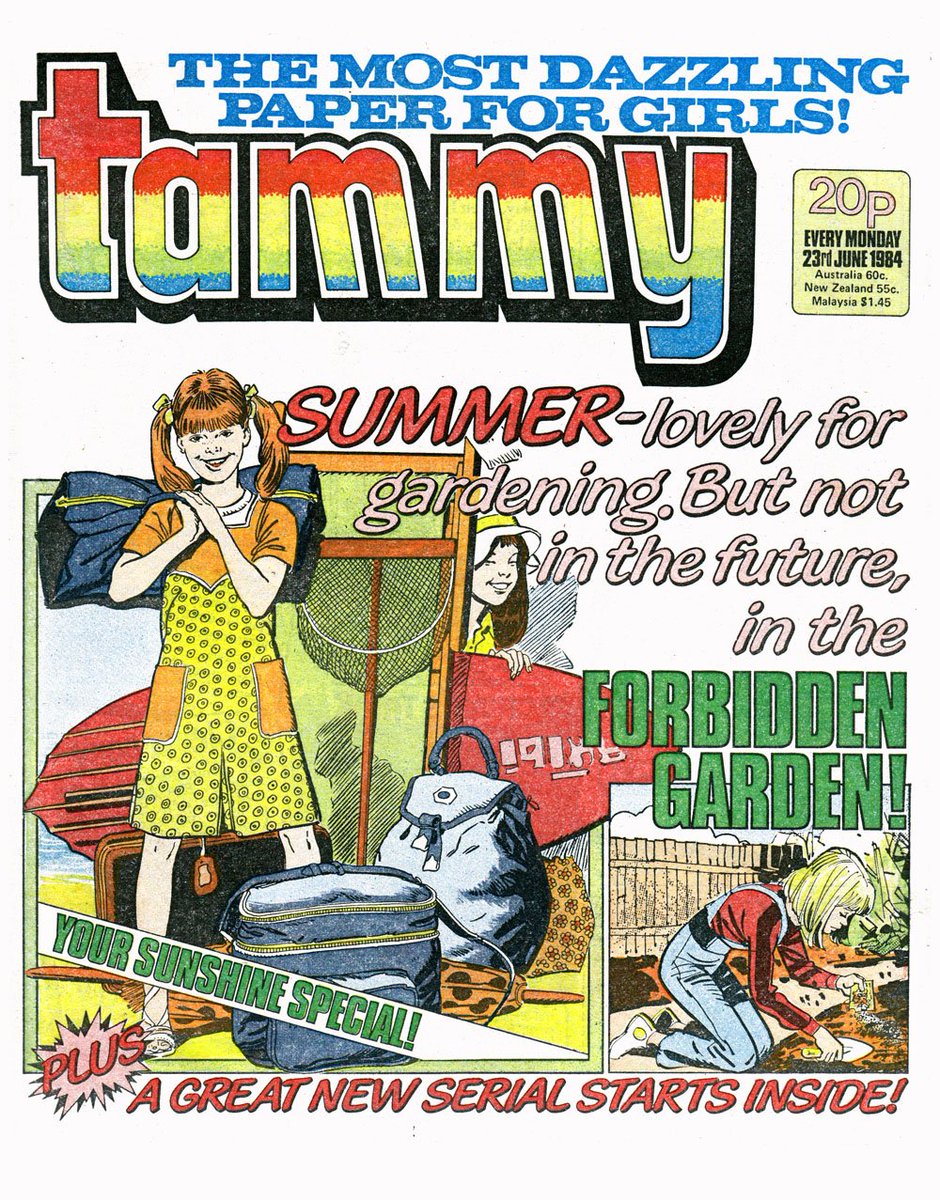

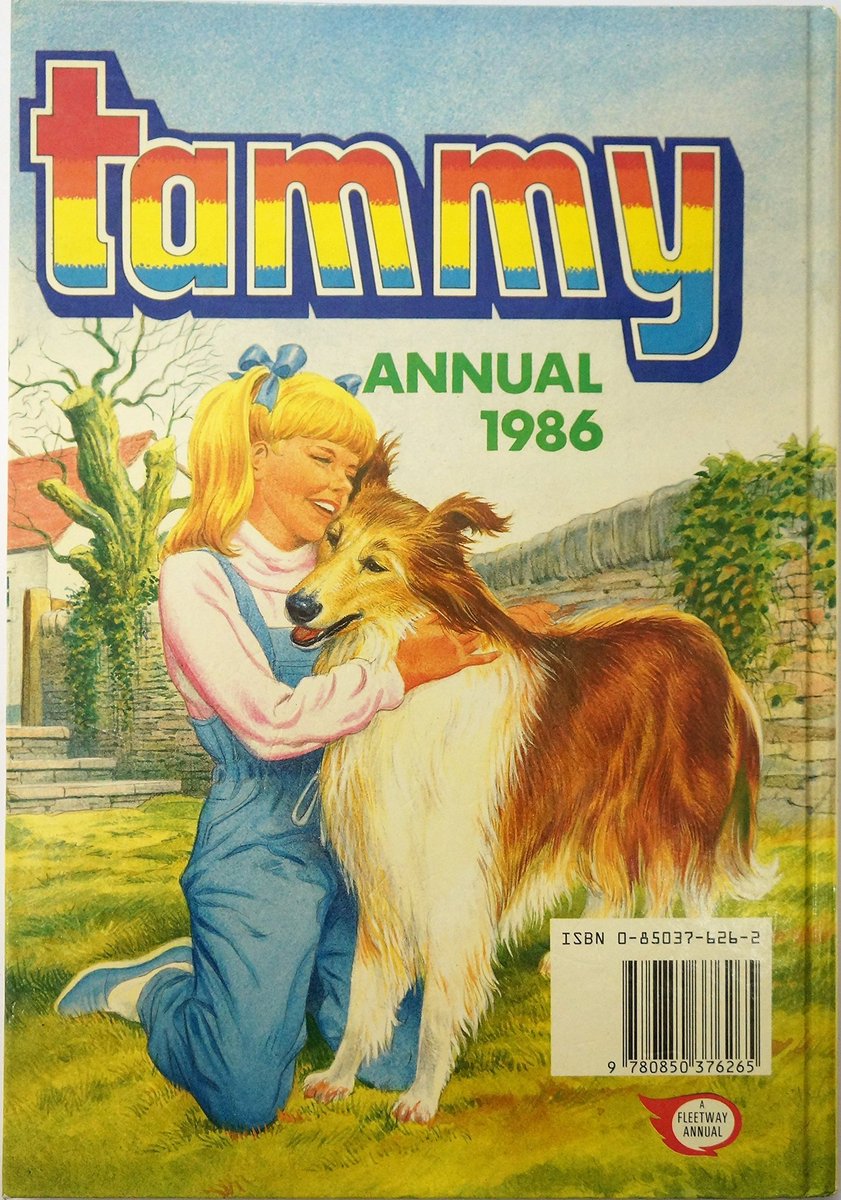

Monday 23 June 1984 seemed like a normal day. The latest issue of Tammy was out, with the latest instalment of The Forbidden Garden and the new Secret Sisters strip. Little did we know it would be the last issue ever!

Today in pulp I ask: whatever happened to Tammy?

Today in pulp I ask: whatever happened to Tammy?

British girls' comics have a long history, starting out as story papers in the 1920s and 30s. Public schools, caddish sorts and lots of healthy outdoor activity were the main staples of the genre...

Postwar the girls' comic template was firmly set in 1951 by Girl, the sister paper to The Eagle. Adventure, duty and jolly hockey sticks were the order of the day.

IPC acquired Girl in 1963, so you can guess what happened next...

IPC acquired Girl in 1963, so you can guess what happened next...

...it was merged with Princess the following year. IPC had a reputation for merging successful comics, often on a whim, to keep the market fresh. Princess herself merged with Tina in 1967 to create Princess Tina.

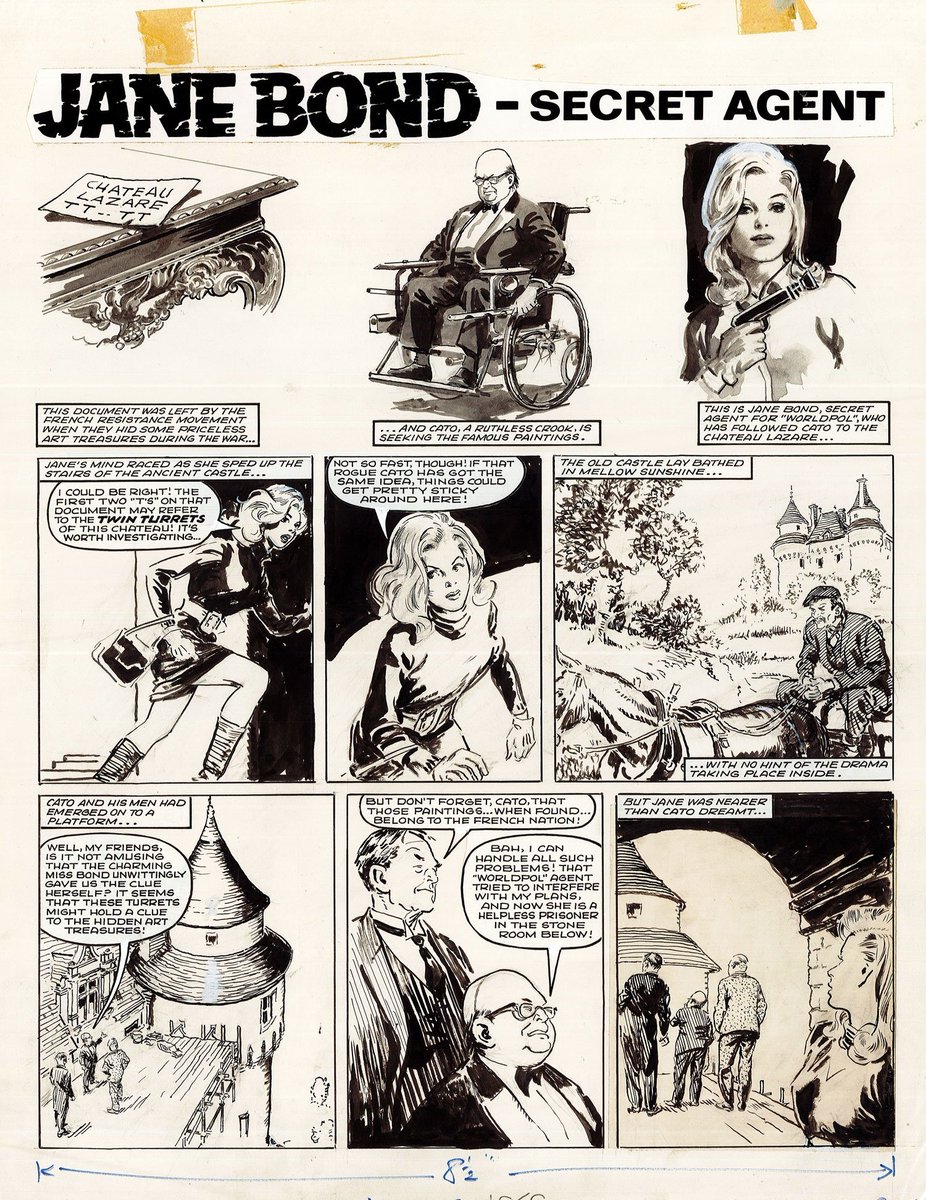

By the late 1960s girls' comic strips were starting to change in Britain, influenced by Emma Peel and other strong female characters on TV. Excitement and adventure were in, school tuck shops were out!

But not in Bunty: D.C. Thomson's best selling title for girls remained an oasis of sensible teens, puppies, ballet dancing and dressing up.

However IPC were about to launch something that would kickstart a comics revolution...

However IPC were about to launch something that would kickstart a comics revolution...

Tammy launched on 6 February 1971, and looked like a traditional comic for girls: free gift, flowery masthead, smiling faces.

The content however was anything but traditional!

The content however was anything but traditional!

"Slaves of War Orphan Farm", "Castaways on Voodoo Island" - Tammy was bringing a grittier type of story to its readers and would continue to do so for the next 13 years.

In essence Tammy was bringing the girls' comic genre down to earth: plucky working class girls fighting the odds; mysterious stories of adventure and horror; drama, tragedy and cruel fate. It was a huge success and influenced many other titles, not just its IPC stablemates.

And as the years went by Tammy started to eat up its rivals.

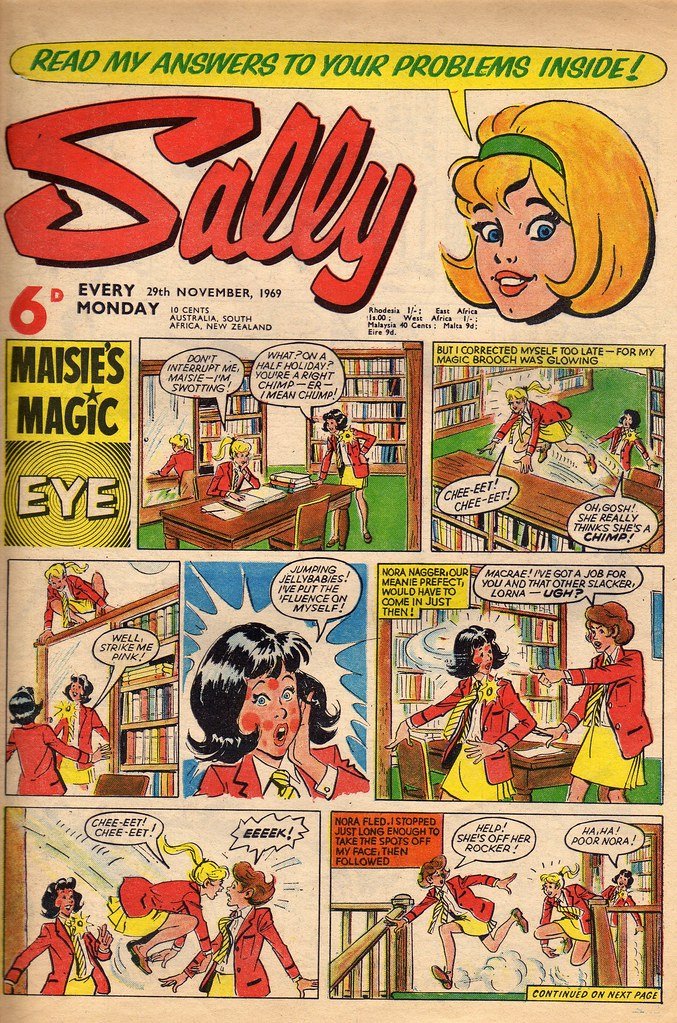

First to go was Sally, a more traditional comic gobbled up in 1971.

First to go was Sally, a more traditional comic gobbled up in 1971.

Then in 1974 Tammy swallowed June - one of the bestselling comics of the 60s which had already devoured Poppet, Schoolfriend and Pixie!

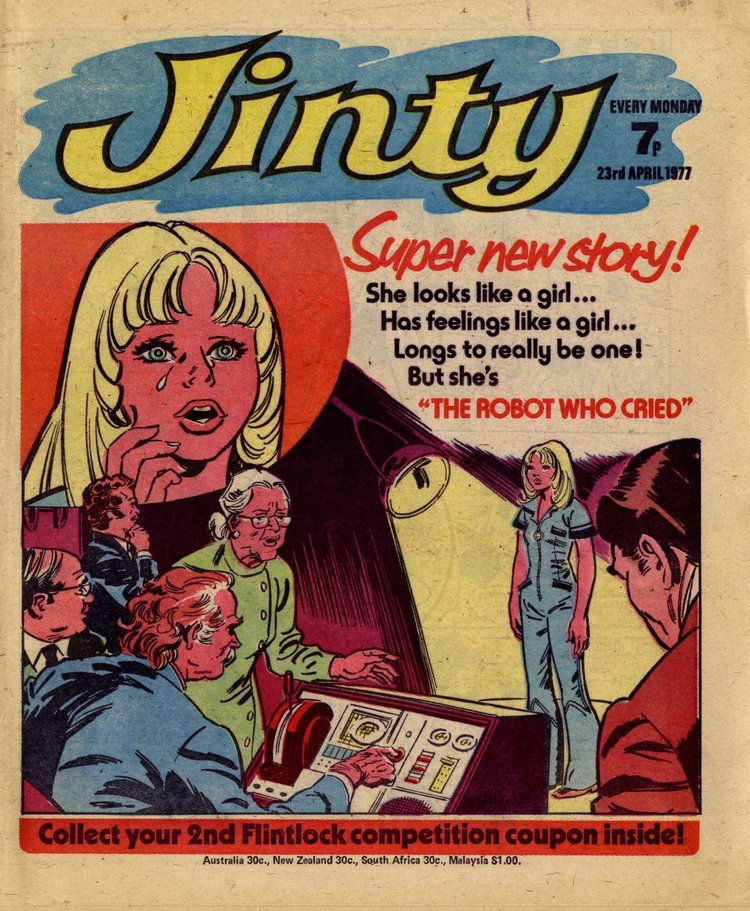

By the mid-1970s Tammy had reshaped the girls' comic scene, and not just through mergers: it proved there was an appetite for tougher stories out there. Both Jinty (launched 1974) and Misty (launched 1978) rode this new wave of mystery and terror.

Then the inevitable happened...

Then the inevitable happened...

It was a terrible day, 19 January 1980, when Misty - the finest supernatural comic ever written - was laid low with the dread phrase "important news for all readers"...

Tammy had taken it over!

Tammy had taken it over!

What IPC hoped to achieve by this hideous crime is unknown. All we can say is that Misty herself vanished into the world of Christmas Annuals and childhood memory.

More was to come...

More was to come...

Jinty was a powerhouse of girls' science fiction and fantasy. There really was nothing else like it: sales were good and the stories were solidly written imaginative works.

But by the end of 1981 Tammy had merged with it, and Jinty was no more. Could anything stop this juggernaut?

Certainly not the revamped version of Princess IPC launched in 1983. By 1984 Tammy had taken that over too. In short it seemed that nothing could stop the title.

So why did it mysteriously vanish in June '84? What happened?

So why did it mysteriously vanish in June '84? What happened?

Well it seems plans were already afoot to merge Tammy into Girl magazine in late 1984. However industrial action at IPC meant the final pre-merger Tammy editions could not be produced. Instead IPC just didn't resume publication of Tammy after the strike ended.

Like many former IPC titles Tammy continued as a stand-alone Christmas Annual for a few years, but without completing any of the stories that had ended mid-run when the original comic closed.

But the story doesn't quite end there...

But the story doesn't quite end there...

Because in 2019 Rebellion Comics brought out a new Tammy and Jinty special, including all new Bella At The Bar!

There are many excellent blog sites detailing the history of British girls' comics:

- Jinty and Tammy: jintycomic.wordpress.com

- Misty: mistycomic.co.uk

- Bunty: girlscomicsofyesterday.com

- Lew Stringer's blog: lewstringer.blogspot.com/?m=1

More girls' comics another time...

- Jinty and Tammy: jintycomic.wordpress.com

- Misty: mistycomic.co.uk

- Bunty: girlscomicsofyesterday.com

- Lew Stringer's blog: lewstringer.blogspot.com/?m=1

More girls' comics another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh