'Bodily Dirt' as a source of deadly germs: Hygiene practices in Sahibs’ Bungalows

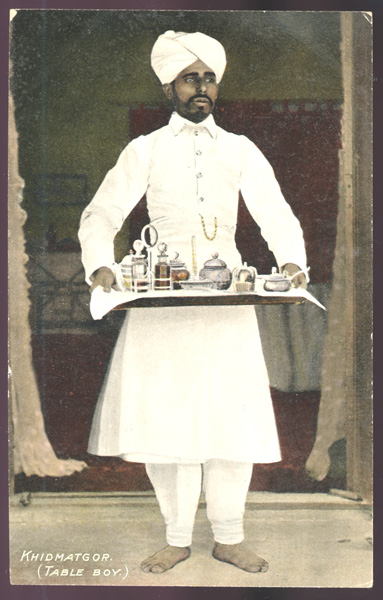

Anxiety about Indian dirt, in general, was particularized onto individual servants as potential careers of deadly germs into the household on their bodies. [1/6]

Anxiety about Indian dirt, in general, was particularized onto individual servants as potential careers of deadly germs into the household on their bodies. [1/6]

Andrew Balfour, writing in 1921, advised that ‘wherever possible it is a wise precaution to have native servants medically examined before engaging with them’. The hands of servants were regarded with particular distaste. [2/6]

During a Cholera scare in the 1930s, Margery Hall made her ayah scrub her hands with Dettol before she started her work, while she personally disinfected the dishes before and after meals and used disinfectant liberally throughout the compound. [3/6]

Sweepers were regarded with particular suspicion, and while in the bathroom he was not supposed to touch the basins or the bath. They were allowed to enter bungalows of Sahibs and one Mrs. Taylor recalls in her diaries that ‘she never allowed them to touch anything. [4/6]

As Mary Douglas argues, these practices were not simply a response to the presence of pathogens but as attempts to maintain the order of things. More than a manifestation of worries about health, it was an attempt to impose a European system of order onto alien surroundings.[5/6]

A haughty manner was often employed which, as Dane Kennedy suggests, ‘served as a psychological substitute for the physical separation of the races, an attempt at emotional disengagement from the indigenous peoples encountered in daily life'. [6/6]

Sources:

(i) Vigarello, Concepts of Cleanliness

(ii) Balfour, ‘Personal Hygiene’

(iii) Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger

(iv) Dane Kennedy, Islands of Whites

(i) Vigarello, Concepts of Cleanliness

(ii) Balfour, ‘Personal Hygiene’

(iii) Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger

(iv) Dane Kennedy, Islands of Whites

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh