Bob Dylan thread

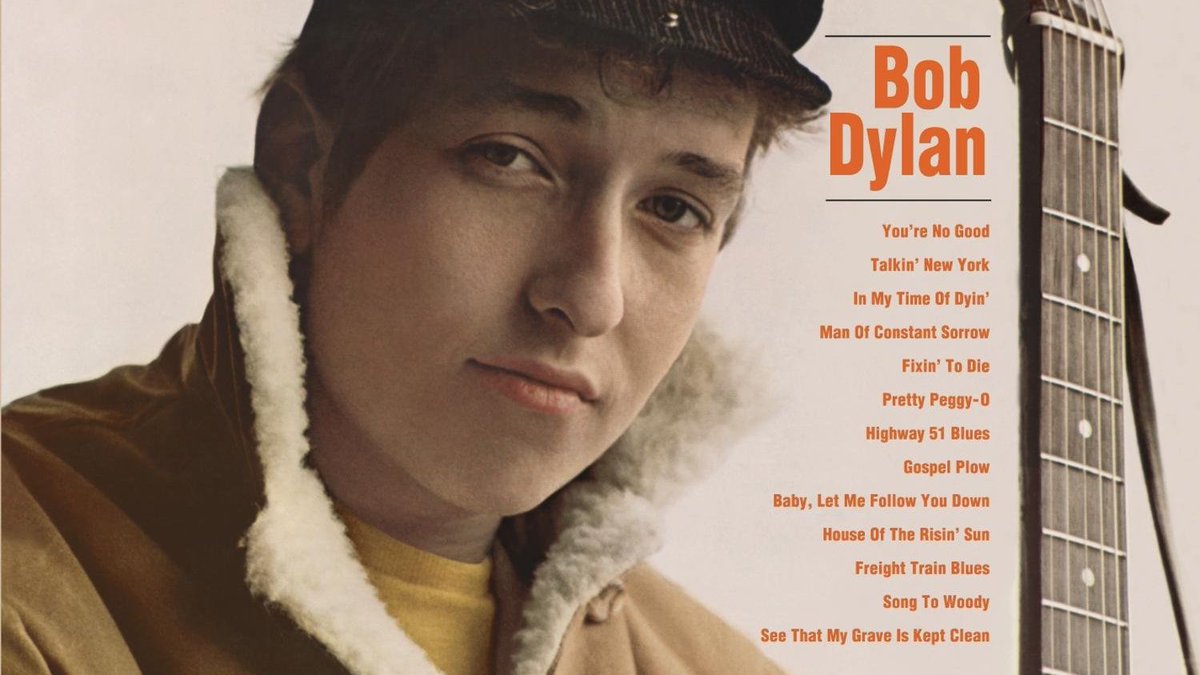

Bob Dylan: More serious Dylanites — a group that at this point includes most everyone who's ever listened to the man — have suggested to me that his debut album can safely be skipped, consisting as it mostly does of covers. But I'm afraid that's not how I do things around here.

This is clearly a product of what A Mighty Wind called "the great folk music scare of the early sixties." Six of its thirteen songs are credited as "traditional," and three to songwriters born in the 19th century — but this, just before the rock revival, seems to have been cool.

Not that the 21-year-old Minnesotan was doing it in quite the acceptedly cool manner. Perhaps the best known line on the album, from one of his originals, sums up his early reception in New York: "You sound like a hillbilly. We want folk singers here."

Unrepresentative though this one may be of Dylan in full, I do appreciate the obvious insouciance of its recording (during which Dylan refused, for example, to pay any song twice) and the coming journeys down darker, more winding backroads of Americana it seems to promise.

The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan: According to the accepted mythos, the Bob Dylan of his self-titled debut wasn't yet Bob Dylan, just a young folk singer with a fairly distinctive style. Only with this follow-up, brought out the following year, did Bob Dylan become Bob Dylan the icon.

What with my lack of familiarity with most of his oeuvre, I was actually surprised by how unmistakably he sounded like Bob Dylan on that first album. But even I can sense a sharp intensification of Dylan-ness here; to my ears, in fact, he already sounds maximally Dylan-esque.

Much of the change has to do with subject matter. As the Beatles and the Stones do on their own early-60s albums, Dylan starts out relatively heavy on the covers and then moves toward originals — showing, in so doing, that you don't necessarily have to write simple long songs.

Despite my long indifference to (but never distaste for) Dylan, over the years I couldn't help but notice how many of the musicians I've actually listened to — Van Morrison, Steely Dan — credit him with introducing them to the notion that they could write about anything at all.

The suite of topics Dylan takes on here ("this equality-freedom thing," as he unimprovably put it) date the album, to be sure, but in a manner that's been celebrated rather than derided. Still, I can't put it on without thinking of this Big Nate strip that cracked me up as a kid.

A few years thereafter — but still before I'd ever heard "Blowin' in the Wind" — the Simpsons made sure I knew the answer to the question of exactly how many roads a man must walk down before you call him a man:

The troubles impressionistically rendered on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan seem mostly to do with racial and nuclear conflict. This suggests I should file the album as an artifact of Cold War culture, as does its oscillation between earnestness and jokiness.

Though humorous cultural references have been my main source of Dylan familiarity so far, covers surely come second. This album has the original of "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right," Bryan Ferry's version of which I've been hearing for nearly 20 years:

The sole "folk" musician into whose work I've gone deep is Nick Drake. His Cambridge-pastoral act has something in common Dylan's of backwoods urbanity — as, with harmonica instead of strings, the English-inspired "Girl from the North Country" reminds me:

The Times They Are a-Changin': If any one thing put me off listening to Bob Dylan until now, it was my perception of a certain self-seriousness that I also suspected was unfounded. And indeed, much of what I've heard so far has been cut with humor. But this album certainly isn't.

Dylan fans seem to value him for an unchanging musical core, of whatever that may consist, but a major appeal to me of listening to an artist like him is how reliably his work reflects trends over a relatively long stretch of recent history. Here he goes from "folk" to "protest."

With its subjects like dispossessed miners, the assassination of Medgar Evers, and family annihilation by impoverished farmers, The Times They Are a-Changin' was considered a bummer even at the time — but fortuitously for Dylan, it happened to come out in a bummer of a time.

After the death of JFK but just before the stateside arrival of the Beatles, this album could well be said to have inadvertently captured the zeitgeist. And the unsubtle sentiment of the title cut was certainly well-placed to provide an anthem to the emerging youth culture.

Both the song and the album were known to be favorites of Steve Jobs, which suits his apparent humorlessness well enough — as well as the regret someone of his age and temperament would surely feel about just "missing out" on an era of great perceived potential for social change.

Despite having yet to dive into the vast corpus of Dylan-related writings, I get the sense just from the music that Dylan himself could run hot and cool on the political stuff. To my ear, the most impressive songs on this album are the non-political ones.

("Boots of Spanish Leather" at first sounded to me like a retread of "Girl from the North Country" off the last album, but both turn out to be based on "Scarborough Fair" — and thus relatively non-dated examples of Dylan's penchant for repurposing much older musical forms.)

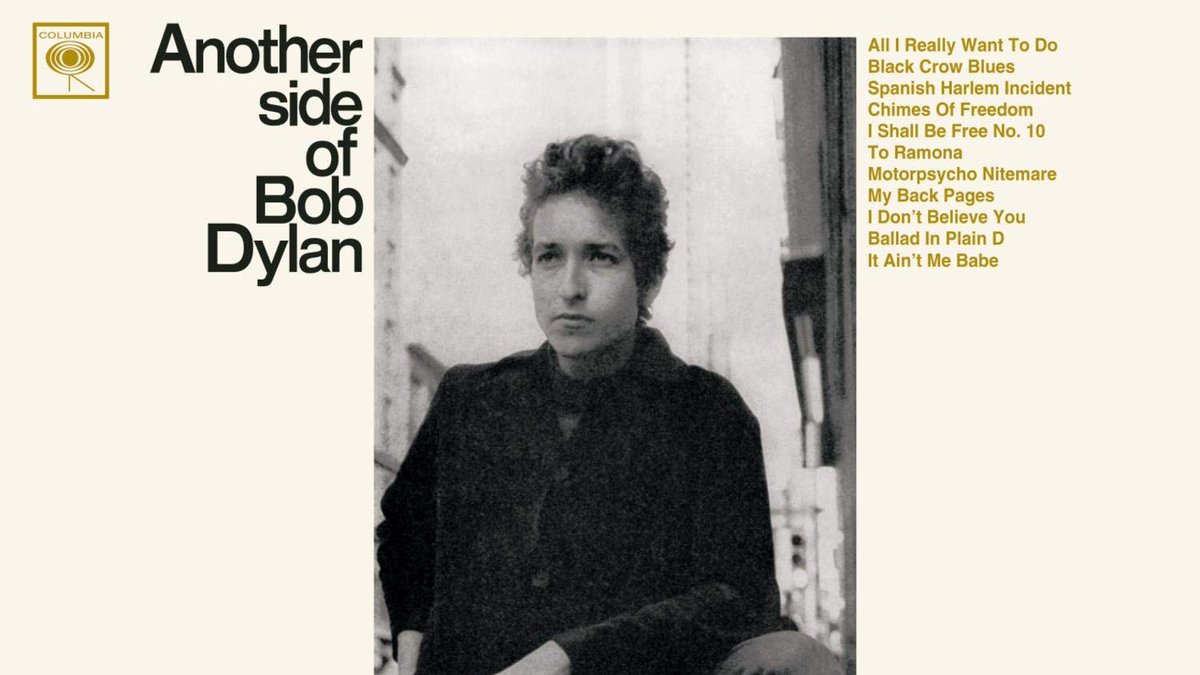

Another Side of Bob Dylan: This was quite a shocking album in its day, from what I've heard, expressing as it does a defiance of the expectations to which folk and protest singers were held. Bob Dylan still sounds like Bob Dylan, but now all the songs are about Bob Dylan as well.

One of my main motivations for listening to the entire discographies of much-written-about artists like Dylan is precisely so I can enjoy all the writing done about them. Take this piece by Nat Hentoff, who was present at Another Side's recording session: newyorker.com/magazine/1964/…

That's session, singular, with vocals, guitar, harmonica, and piano by Dylan alone with the microphone, though Hentoff does note that his more unhinged talking-blues numbers could crack up the guys in the booth (and Dylan himself breaks into the occasional chuckle on the record).

Another motivation, perhaps subsidiary to that first one, is a desire to more fully grasp the Dylan references still made so often in other parts of the culture. On this particular album, has any song been more often referenced than "My Back Pages"?

I remember first encountering his line about "the mongrel dogs who teach" as the epigraph of a favorite book decades ago. Or maybe it was an essay, or a web site — I can't recall, and the very popularity of the song renders the question un-Googleable. The rare vanished source.

Most of all, at least in listening to the music of this specific period, I've wanted to grasp the inter-artist competition to create ever more ambitious albums — hence first going through the Beatles and the Beach Boys. Lone-wolf pose notwithstanding, Dylan wasn't quite above it.

Dylan lore has him introducing the Beatles to cannabis soon after the release of this album — and having his mind blown by "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" some time before its recording. But then, Brian Wilson claims to have had the same experience — as, it seems, do all their peers.

Bring It All Back Home: I wasn't sure whether to acknowledge Bob Dylan's recent, much-remarked-upon 80th birthday here, but it would've been conspicuous not to. In any case, it gave me occasion to consider the parallel historical timelines this discography-listening puts me on.

In the timeline I actually live on, Dylan is an octogenarian cultural icon, already as established as they come (and also, from my childhood perspective, "old") even when I became aware of him. But in the timeline I'm listening on, he's a 23-year-old who just went electric.

Though I have yet to hear any Dylan album newer than this one, never in my life have I not been surrounded by Dylan references. I cited the line about mongrel dogs last time; this time I recognize "the pumps don't work 'cause the vandals took the handles."

I remember seeing that line, too, quoted in a piece of writing I liked growing up. But now I have no idea what piece it was, and indeed find it impossible to imagine a context in which it could be relevant. Yet the words stuck with me, despite my not having heard the song itself.

That very memorability, as I now see it, constitutes much of the appeal of Dylan's lyrics. One could complain that "the pumps don't work 'cause the vandals took the handles" means nothing, but that at least beats most popular music of the time, whose words mean exactly one thing.

The same semantic narrowness afflicts today's popular music, as well as popular music of every other era, and so it stands to reason that the veneration of Dylan on that level would continue over the past half-century — though that veneration also kept me from listening to him.

This album includes "Mr. Tambourine Man," perhaps the Dylan songs I've heard the most times over the years, always involuntarily. And though I don't dislike it, it would never cross my mind voluntarily to listen to it; it sets off no resonances within me.

I suspect I'm objectively wrong not to engage with "Mr. Tambourine Man" more than I do, since trusted sources (e.g. Tyler Cowen) name it among Dylan's finest songs. Yet in an 80th-birthday tribute list, only two other musicians name it as their favorite: stereogum.com/2147461/favori…

David Byrne, with whose work I'm more familiar, doesn't choose "Mr. Tambourine Man," but he does write about it in his contribution to the list (in which he selects a Dylan song released just last year), the kind of transmission-from-another-world cultural memory I savor hearing:

The song reached Byrne through the Byrds. I, too, first heard Dylan's work mostly through covers; I mentioned Bryan Ferry's "Don't Think Twice, It's Alright" before, which comes from an album that opens with a version of Bringing It All Back Home's closer:

Listening to Ferry's version of the song for nearly twenty years, I couldn't help but — despite always knowing of Dylan's authorship — internalizing it as the "real" one. Consequently, the original sounds to me like a simplified and mildly abrasive cover:

Highway 61 Revisited: Like Pet Sounds, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, or Exile on Main Street, this is an album almost too freighted with cultural baggage to approach. But it predates all of those, and in some quarters is even credited with having started "the Sixties."

Much of that weight is carried by the opener "Like a Rolling Stone," which you don't have to be deep into Dylanite circles to hear called the greatest song ever recorded — or at the very least, the most influential song recorded in its decade.

As Dylan's biggest hit single, "Like a Rolling Stone" has long been inescapable, though not quite to the punishing extent of its Beatles/Beach Boys/Rolling Stones counterparts. Unsurprisingly, it was also the only song on Highway 61 Revisited with which I myself was familiar.

Anyone can appreciate the anthemic quality of "Like a Rolling Stone," which up to this point hasn't been a major element of Dylan's music. But the question that interests me is less what I like about the song now than how it might once have torn down and rebuilt my worldview.

Many claim to have had their minds rearranged by this song or those of Dylan/the Beatles/the Beach Boys/the Stones more broadly. "I Want to Hold Your Hand," as I've mentioned, did it to Dylan himself; the impact of "Like a Rolling Stone" seems to have been narrower but deeper.

A longing for this sort of experience has done its part to motivate my own pilgrimages through the discographies of these artists. But part of me suspects I'm too late: too late in the sense that it isn't the mid-1960s, yes, but also too late in the sense that I'm in my mid-30s.

Yet the longer perspective of cultural history compensates somewhat. 56 years later, we see (or hear) more clearly what lyrically oblique six-minute song driven bitter resentment did to expand the field of possibility in the world of pop music, then dominated by bland love tunes.

I'm reminded of the renewed discussion of Citizen Kane brought about by the film's recent 80th anniversary. Welles' accomplishment is to be appreciated for its own qualities, but even more so for the way it ignored so many of the conventions of its medium, freeing cinema to come.

This album's influence is hardly difficult to come by. For my part, I can't hear "Queen Jane Approximately" without hearing Steely Dan's "Brooklyn Owes the Charmer Under Me" (on Can't Buy a Thrill, a title taken from another Highway 61 Revisited song):

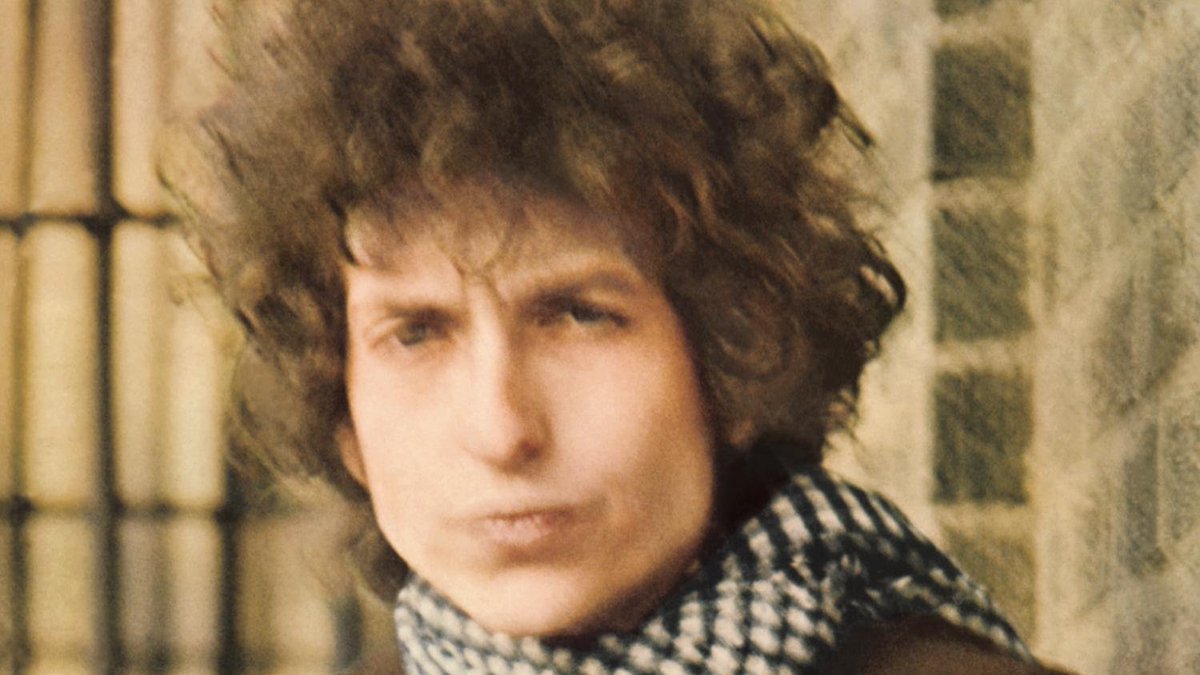

Blonde on Blonde: In the discographies I've been listening through, I've come to realize, the double album is an inevitability. The Beatles had the white album, the Stones had Exile on Main Street... but come to think of it, the Beach Boys never did record a proper studio double.

Still, the double-album compilation Endless Summer did bring the Beach Boys back to commercial life in the 70s, which says something about the format's relevance in that era. But as I understand it, Dylan's Blonde on Blonde is the double album that, in 1966, started it all.

This project still today receives critical respect commensurate with its length. Here we have the crowning achievement of the trilogy that begins with Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited — a masterpiece that happens to open with a gag song:

I had a vague sense of this album's place in the Dylan canon, though I didn't know it was the product of a deliberately engineered culture clash: this icon of New York City hipsterdom (in the early-60s sense) recorded it in Nashville, the red-hot center of American country music.

With certain of these classic double albums it can be tricky to find a "way in," but Blonde on Blonde presented me with an especially clear one: the line "Aww, mama, can this really be the end?" from "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again."

My early introduction to Sixties culture came much less through the work of any musician than it did through the writing of Hunter S. Thompson, an interest I picked up from my dad. Even casual Thompson readers know this line of Dylan's appears in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas:

Amusingly, Dylan sings the line exactly as I'd imagined he would while reading the book. In fact, throughout much of this album from "everybody must get stoned" onward, he sings like someone doing Bob Dylan — and in one case, like John Lennon doing him:

Listening through the Stones' discography, I paid special attention to songs Wes Anderson had used in his movies, or songs that sound like he could have used them in his movies. So far, I've heard from Dylan no more Andersonian a song than "I Want You":

And have I heard a more Andersonian song at all? Despite feeling sure that "I Want You" has never been in a Wes Anderson movie, I was still surprised to find that indeed it hasn't. Still, I've heard Anderson is now gearing up to shoot his next project; maybe the time has come.

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: I last revisited Dont Look Back after the death of D.A. Pennebaker a couple of years ago. I'm not sure why I'd seen it even before then, given that I had yet to listen to a Bob Dylan album — and the portrait painted by the film hardly encouraged me to do so.

The ostensible subject is Dylan's 1965 tour of England (the reverse, at a much smaller scale, of the Beatles going to America the year before), but the film is valued less for its concert footage than its behind-the-scenes material, in much of which Dylan comes off like a jerk.

This behavior hits a crescendo with his long, incoherent savaging of an interviewer. But the scene does remain compelling today due to the ambiguousness of what Dylan's intent. Was he doing a character? Expressing grievance against Time magazine? On drugs?

But it's less compelling than the negotiations in which Dylan's manager Albert Grossman engages to wring out the biggest possible fee for a TV appearance. Grossman is remembered for knowing full well how far his client would go — or at least projecting great confidence about it.

Looking back (as we've been told not to), all this plays like a study on the effects of sudden, massive adulation on a still rather young individual. "Did we actually once take this twirp as our folk god?" asked Roger Ebert in the 1990s. But the twirps shall inherit the Earth.

John Wesley Harding: A return to down-home Americana signaled by the titular opener, named (and slightly misspelled) for a supposedly honorable Old West outlaw — a category of figure that holds a much larger place in the imaginations of many Americans than it does in mine.

It's actually a tough call to say which 19th-century American character holds less inherent interest for me: the principled gunslinger who meets his grim fate in the territories of the West, or the urban scamp barely removed from the old country who makes good in the East.

Here Dylan turns away from the songs of himself that characterized his previous three albums, reviving his previously indulged sentiments of concern for his downtrodden countrymen. Three songs in a row: "Dear Landlord," "I Am a Lonesome Hobo" and "I Pity the Poor Immigrant."

Another of the ways in which John Wesley Harding breaks from Dylan's then-recent work, so I've read, is in his heavy consultation of the Bible in writing many of its songs, setting down the lyrics before the music. The apparent rhetorical and thematic effects are hard to un-hear.

Dylanologists may see in this Biblical songwriting a root of his later conversion to Christianity. I see in it his formidable ability to get down to and use the essential elements of American culture, which is much more obvious in the album's veneration of the permanent outsider.

Nashville Skyline: I'd heard Dylan uses a different voice on this album, part of its declaration of intent to go full-on country, but I was surprised to hear just how different that voice is. If I'd only heard the first cut, I doubt I'd have been able to identify him at all.

Or I doubt I'd have been able to before listening to Dylan's discography, since that opener is a country cover of his own "Girl from the North Country," a song I found notable on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. And for credibility, it features Johnny Cash:

Freewheelin' had come out six years and seven albums before. To this point, Dylan has gone through five distinct stylistic "periods" at the very least. This is one of the fascinations I'd vaguely expected of the Dylan canon: if you don't like one Dylan, another'll be along soon.

As he enters each new period, Dylan seems to insist that it reflects the music he meant to be playing all along. "I am certain Dylan is sincere," writes Robert Christgau of the country turn, "but I am also certain that he was sincere about protest music when he was into that."

Few would call Dylan a "rock star," not least due to his genre-hopping, but perhaps he stands as an even more deeply aspirational figure than that. We all want our caprices to be taken seriously — indeed to take them seriously ourselves — but could anyone but Dylan pull it off?

In the briefest song on this brief album, Dylan expresses his enthusiasm for country pie. I believe these sentiments are not just sincere but eternal. Here's an alternate take of the song, since the album version is (I assume) too good for Youtube:

Self Portrait: I'd been waiting for this one, having gathered not only that it was Dylan's worst, but that it belonged in the category of legendary unlistenability alongside, say, Metal Machine Music. And of course there's Greil Marcus' "What is this shit?" Rolling Stone review.

When I actually read Marcus' piece, it turned out to be characteristically thoughtful, "What is this shit?" just a provocative reflection of one of the reactions in the air (albeit a seemingly common one). As for the album itself, it turns out to be disappointingly listenable.

Self Portrait is a double album, and not one in which I can find any particular coherence. Many of its songs are covers (including, bafflingly, "Blue Moon"), and some are recordings of a live show on the Isle of White (such as a country-crooned version of "Like a Rolling Stone").

The best description I've heard comes from Dylan himself, speaking years later: what with all the bootlegs circulating, this was an attempt to make "my own bootleg record." Elsewhere he mentions wanting actively to put off the hippie fans who'd come to expect prophecy from him.

Having grown up listening to the Shaggs, I have a high (or rather low) standard for "bad" Sixties music. I'm unlikely to listen to Self Portrait ever again, due not to badness but its dullness. Yet as with most "bad" albums, I can hear it telling me something about its era.

The attacks on the album reflect hugely exaggerated expectations of Bob Dylan. "For the first time, the rock culture was faced with a Cinerama-sized example of creativity running out of road," wrote Clive James of this period. "A full-scale intellectual crisis rapidly developed."

And "since Dylan's stock of instinctive, unstudied spontaneity was almost incomparably more abundant than anybody else's, his limits lay a long way down the pike. But eventually he got to them." The tank of gas he started out with ran dry, as it does for every artist or band.

For all the acts of this generation whose discographies I've been listening through, this seems to have happened round about 1970. In the Beatles' case, of course, it broke them up — and then came the postscript of Let It Be, their own "bad" album:

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1250928566012801024

Let It Be and Self Portrait have a lot in common. "Ruined" in production with strings and other overdubs (bête noire of the Sixties connoisseur, it seems), they both met with acclaim in stripped-down versions decades later — neither of which figure into my own listening project.

In any case, before coming to any rash judgments, it's important to give every album the necessary five decades of listening:

https://twitter.com/MineralDisk/status/1395196714680782849

New Morning: A "return-to-form" album — and not, I suspect, the last one I'll encounter in Dylan's discography. Mostly recorded before the reviled Self Portrait was released, it seems nevertheless to have been received at the time as the work of an artist chastened by failure.

That's not to say that it met with a lukewarm reception: on the contrary, ecstatic contemporary reviews aren't hard to turn up. "WE'VE GOT DYLAN BACK AGAIN!" exclaimed the Rolling Stone headline, and what they had back were Dylan's original songs, as well as his original voice.

Half a century later, critical opinion about this album seems to have settled on "pretty good." And indeed, it strikes me as a well-produced showcase of Dylan's skills of this period, especially turning a clever phrase and performing credibly across a range of American musics.

Competent albums of this kind are difficult to consider retrospectively. You could say New Morning reflects the early-70s ascendance of country rock, but it can't say as much about the times, or about Dylan himself, as would a more daring project — especially a daring failure.

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: Bob Dylan recorded the music for as well as played a role in Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Peckinpah would later claim that Dylan had been foisted upon him, but even if that's true, it would have been the least of this production's problems.

The Western as a film genre had already gone into its long twilight by 1973. The old Hollywood studio system had also, from what I've read, seen much better days. In bitter conflict with MGM, the famously combative Peckinpah finally had the picture taken from him and bowdlerized.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid's studio cut seems to have been received as dreary and incoherent. But since then the film has been re-released in a version that aligns more closely with Peckinpah's vision. This cut has, in a Heaven's Gate-type reassessment, drawn great acclaim.

Much in the movie is extraneous to the relationship between the two title characters, the iconic outlaw and the former partner-in-crime bought by the civilizers of the Old West (themselves corrupt, of course) to bring him to justice. So is Dylan's taciturn knife-thrower, Alias.

One of Dylan's musical contributions (about which more later) to this powerful "revisionist Western," as it's now regarded, has become a cultural phenomenon in its own right. But whichever the cut, his acting has moved few to suggest he quit his day job.

Dylan's music reflects an abiding interest in American outlaws, and his participation is said to have been motivated by fascination with Billy the Kid. In that role is Kris Kristofferson, who's also somewhat distracting, less by being another musician than by being much too old.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: Dylan's soundtrack album to the aforementioned Sam Peckinpah film. But whether to count it as a full-fledged Dylan album remains unclear to me; as on long stretches of Self-Portrait, he seems for the most part just to be "dicking around" here.

Most of the ten tracks are countryfied instrumentals, which do more or less reflect certain moods of the film. There are only two proper Dylan songs, and one of them, the main theme "Billy" that even fans don't really like, appears in three versions with lyrics and one without.

At least one "Billy" suffers from conspicuous mic popping, which strikes me as unbecoming of a world-famous singer-songwriter recording for a major motion picture. But carelessness, whether accidental or deliberate, is a recurring and distinctive characteristic of Dylan's work.

No doubt that working off the cuff has allowed Dylan to create more than enough enduring work to balance out all the forgotten misfires. Take "Knockin' on Heaven's Door," the only widely valued song on this album — and one that has transcended its origins:

With the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Rolling Stones, even most of the flubs went through a pretty intensive studio process; with Dylan, even the standouts sound tossed off. This approach to creation necessitates an approach to listening that I admittedly have yet to master.

Dylan: The rare album by any artist — certainly the only one by Bob Dylan — to receive an "E" grade from Robert Christgau. But then, it's not properly a Bob Dylan album: after he left Columbia, they pieced this one together out of leftovers from Self Portrait and New Morning.

Whether for legal reasons or because there wasn't anything else, every track is a cover, either of a traditional song or an existing hit for another artist. It surprised me to hear "Can't Help Falling in Love," though I can see how it'd be in his purview.

Christgau is hard on the performances, but some of the songs themselves are also preachy, from "The Ballad of Ira Hayes" to "Big Yellow Taxi," which I sometimes misremember Tom Lehrer as having called "the most sanctimonious song ever written." (It was actually "Little Boxes.")

What all this lacks in musical appeal it perhaps makes up in interest as an artifact of the history of the industry. How long has it been, after all, since an artist stirred up a fuss by leaving his label — and the label stirred up more by issuing one last cash-in under his name?

Planet Waves: In 1974, albums by the likes of Wings, Chicago, Elton John, and the Carpenters had their time in Billboard's top spot. But so did this Planet Waves by Bob Dylan — his first such number-one — which didn't bend to the "smooth" production styles then in the ascendant.

Critics give Dylan credit for sticking to his roots-rock guns in the face of 70s musical fads that have aged less well. But you could say that roots rock itself was a 70s musical fad; the year before, even the Beach Boys had put out an album of the stuff.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1299198669506322432

In 1974, Steely Dan (to pick an admittedly extreme example, but one I know well) recorded Katy Lied, the album that market a big step toward their signature perfectionist studio process. Dylan, by contrast, recorded the entirety of Planet Waves in six mostly non-consecutive days.

He did so with The Band, in their final official collaboration. I haven't given much thought to The Band in my consideration of Dylan thus far, but the references I've heard to their debut album Music from Big Pink makes me imagine it as a "key" to swathes of music from this era.

Dylan's unwillingness to ride, as it were, the waves of popular music — or to do so in a manner parallel but distant enough to set himself apart — is admirable. But a bit more abject trendiness might have made his albums of this period more sharply distinguished from one another.

The Basement Tapes: All my adult life I've been using the phrase "basement tapes" to refer to a certain idea — of a voluminous quantity of poorly recorded, obscurely "personal" material of interest only to an artist's die-hard fans — only dimly aware of its origin with Bob Dylan.

Now, I've been listening to the entire discographies of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, and now Bob Dylan, but only according to a strict definition: studio albums (and non-holiday studio albums) only. No compilations, no live recordings, no bootlegs, etc.

Dylan has more edge cases that most. With Self Portrait, for example, he made a "bootleg" of his own; Dylan, the 1973 album, was assembled without his participation. These songs, recorded with The Band mostly in a literal basement, seem not even to have been intended for release.

They thus don't constitute the kind of material I would normally listen to on a discographical journey such as this. Or they wouldn't had Columbia not assembled 24 selected tracks into an official release, The Basement Tapes, eight years after the earliest of them were recorded.

Performed by Dylan and/or The Band, these songs are all pieces of lo-fi Americana, and in those circles acclaimed as highly influential. More notable to me is their stark aesthetic contrast with the biggest albums at the time, like Sgt. Pepper or Their Satanic Majesties Request.

In 1975, listeners would have received the unassuming domestic richness The Basement Tapes as a breath of fresh air. For my part, I admit I've by now had it up to here with all the Yazoo Street scandals and the Bessie Smiths and the Ruben Remuses and the crashes on the Levee.

And yet, the full set of basement tapes does exert a draw. Variously released over the past few decades, their most complete set runs over six and a half hours in total. If I listen to all those songs, it'll be for a specific purpose: soundtracking Greil Marcus' book about them.

Blood on the Tracks: A friend of mine describes this as the greatest "break-up album" of all time. As much as I think about albums, that particular category has never crossed my mind. Thus I'm not sure what to compare this to; Rumours, maybe, which is at least also from the 70s?

The songs on Blood on the Tracks are, in any case, commonly interpreted as being about Dylan's failing marriage. They do express a wide range of feelings toward an unspecified woman or women, but I admit I wonder whether I'd have been able to pick up on that theme independently.

I seldom listen closely to the lyrics of any song, trained as I've been by decades of unbidden pop music to expect inanity. A richer engagement with the work of Bob Dylan would, I suspect, require changing those habits (not to say that I've never heard an inane lyric from Dylan).

Some complain that Dylan's lyrics "don't make sense." That may be true, strictly speaking, but it's also clear that the words to his most acclaimed songs are just ambiguous enough to fire up the listener's imagination. Take this album's opener:

Back on Livejournal, there was one guy in my circle whom everyone most respected: of us all he had far and away the best writing skills and most interesting life. His "current music" field was usually occupied by a literate singer-songwriter like Robyn Hitchcock or Leonard Cohen.

But his favorite song, he wrote, was "Tangled Up in Blue." That more than anything else has made me believe that I stand to gain something from Dylan's work. By the same token, I've also entertained the idea of reading every book by Robertson Davies (yes, the guy was Canadian).

Desire: Up to this point, Dylan has been acclaimed as an interpreter of traditional songs, and even more so as a lone-genius poet, a solo visionary. But most of the material on this album he wrote in collaboration with a clinical psychologist/theater director called Jacques Levy.

Still, several of its most notable songs reflect what I've come do consider a thoroughly Dylanesque interest in the American outlaw. In the case of the opener "Hurricane," that interest expands to include the man caught on the wrong side of American law:

"Hurricane" tells the story of then-imprisoned boxer Rubin Carter, known to my generation (if at all) through the movie with Denzel Washington. In the manner of most biopics, it lionizes its protagonist and elides his complications; Dylan's song, safe to say, does much the same.

It also does so in an elaborately literal manner — gone are the oddities and ambiguities of Dylan's earlier lyrics — which may explain its eight-and-a-half minute length. Even longer and more labored is "Joey," a tribute to a mobster who was gunned down just a few years earlier.

The justice system does seem to have done poorly by Rubin Carter, but Joey Gallo makes for a rather less sympathetic subject. History has remembered him as little more than a violent thug, but "Joey" (which Dylan has since pinned on Levy) holds him up as a kind of low-born hero.

("Although the candid propaganda and wily musicality of 'Hurricane' delighted me for a long time," as Robert Christgau put it in his contemporary review, "the deceitful bathos of its companion piece, 'Joey,' tempts me to question the unsullied innocence of Rubin Carter himself.")

However objectionable, that song reflects with its backing vocals and violin accompaniment the evolution of Dylan's sound at the time. But more enduring, for my money — and far more evocative — is "One More Cup of Coffee," a duet with Emmylou Harris:

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: Renaldo and Clara is quasi-documentary, nearly four hours long, partially based on Marcel Carné's Les Enfants du Paradis, directed by and starring Bob Dylan, and prominently featuring both his soon-to-be-ex-wife and his onetime girlfriend Joan Baez.

All this is, of course, good. The film's other attractions include long stretches of Allan Ginsberg chanting, dancing, and holding court, as well as Dylan-associated singer-songwriter David Blue reminiscing about Greenwich Village while playing pinball at an indoor swimming pool.

Even more appealing to me is the fact that Renaldo and Clara is one of the legendarily "bad" movies. When it came out in 1978, even the Village Voice couldn't get a single unambiguously positive take out of the seven critics they'd rounded up to review it: villagevoice.com/2020/05/28/sev…

I understand that most of the material domestically decried as incoherent and self-indulgent is excised in a two-hour edit focusing on the concert footage of Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue — but it's the whole enchilada that was broadcast on TV in Germany, Finland, and the U.K.

This is indeed a "European" vision of America, with its desolate train-window landscapes, its fundamentalist harangues, its wrongly jailed blacks (even the "Hurricane" himself appears), and its disenfranchised natives. (The Germans were probably won over by Indianthusiasm alone.)

Dylan long ago pulled the film from circulation, with the consequence that nearly everyone has seen it only in an audiovisually degraded form. But on some level, this suits its lurid drabness and complicated aimlessness — a sensibility truly of the 1970s.

https://twitter.com/WillSloanEsq/status/1401164469607321600

"The people in this movie, who made such gripping music in the 60s, no longer exist as a cultural force," wrote the Voice's Richard Goldstein. But the 70s have come to fascinate me more, and to me (then not yet born), no film has ever felt more like the actual 70s than this one.

Street-Legal: Though this hasn't been remembered as one of Dylan's "important" works, there's a lot going on in it, not least sonically. Possibly inspired by the death of Elvis, Dylan put together an elaborate (by his standard) band including horn players and lady backup singers.

But from what I've read, this "fuller" sound was captured through characteristically rushed, slapdash production methods; the remastered version in circulation today isn't terribly sloppy, but then, it's supposed to mark a great improvement on the one originally issued on vinyl.

In this album's mix of the personal and the quasi-Bibilical, Dylanites see a harbinger of his coming Christian period. But its best-known songs like "Señor" (with its unpromising subtitle "Tales of Yankee Power") are of a piece with his then-recent work:

Street-Legal sounds surprisingly "normal" as a whole, and certain tracks could almost have come from any other pop craftsman playing to a listenership of grownups — or in Dylan's case, fellow thirtysomething divorcées, an abundant product of 1970s America.

Slow Train Coming: With this one Dylan's Christian period begins in earnest. It also has a striking slickness of production, obvious from bar one, that contrasts with pretty much everything he's recorded before. And I could be wrong, but he seems also to have acquired a "groove."

All of this comes through in the opener. I'd never heard the song before, but I had heard its core sentiment referenced — a sentiment I daresay resonates with me more than anything else I've heard Dylan sing, at least in its most general interpretation.

Though not religious (but also not allergic to such worldviews), I can see the value in accepting that, whoever you are, you're gonna have to serve somebody — or something, anyway. How many of us willfully and knowingly enslave ourselves to our own impulses and call it freedom?

Other song titles include "Do Right to Me Baby (Do Unto Others)" and "When He Returns," but the relatively ambiguous likes of "Precious Angel" and "I Believe in You" are more representative. Most of the material isn't as blunt as the Christian rock all Americans have encountered.

There's clearly something of the defensive zeal of the recent convert about this album, but there was something of the same zeal about Dylan's non-Christian albums as well. To re-quote Christgau: "I am also certain that he was sincere about protest music when he was into that."

Stories of Dylan's impulsive behavior in the studio are many, but at this point I've come to see them as evidence of an instinct for capturing the inspiration of the moment — and an awareness that no inspiration lasts. Perhaps he regarded the Light of the World in the same way.

Saved: Dylan's second Christian album is markedly less subtle than his first. He ups the religiosity, piling invocation of Jesus upon evocation of Jesus, and also changes his sound: though recording at Muscle Shoals again, he mostly trades its signature 1960s soul for gospel.

Though as far as I know Dylan himself wasn't converted by gospel music, there have surely been many brought to Christian faith by its emotions alone. By the same token, there are those who consider the protest song a convincing form of political argument. I'm not in these groups.

In fact, the more a piece of music refers to something extra-musical, the more resistant I feel to it. This may be the prime element of Dylan's work that has kept me away for so long: it too often seems to be not self-contained but "about" something social, political, moral, etc.

Still, there's something in Dylan's delivery of these messages, with this kind of church-music accompaniment, that appeals to my sense of incongruity. Listening from today's perspective there's even something comedic about it; maybe it felt that way to some listeners at the time.

Shot of Love: On the final album in what's now called Dylan's Christian trilogy, as on his albums of any period, the interest he's outwardly pursuing gets mixed with his love life. Hence the title track, which like all crossover Christian rock can be non-religiously interpreted.

"To those who care where Bob Dylan is at, they should listen to 'Shot of Love,'" Dylan told the NME at the time. "It's my most perfect song. It defines where I am spiritually, musically, romantically and whatever else." It's a memorable tune, in any case.

Later there are signs of Dylan's loosening commitment to religious inspiration. Take his strangely belated and generic tribute to Lenny Bruce — who does, however, enjoy a kind of martyr status, which may explain the churchiness of the song's production.

"Lenny Bruce" does, mind you, follow a track called "Property of Jesus." But it's the closer that seems to have drawn practically all of the critical praise, and to be the number from this album that has kept a place in the canon these past forty years:

Infidels: I understand this album is either a Return to Form or a mess. Either way, it's immediately pleasurable to listen to and therefore not easy to trust. Whatever impulse inspired Dylan to de-Christianize his music also seems to have inspired him to go fully mainstream.

This was a couple of years into the MTV era, and for "Sweetheart Like You" Dylan even put out his first genuine MTV video, which has no characteristics of note except for his scrubby beard:

The second video, for the opener "Jokerman," is much more interesting — but then so is the song itself, which I'd easily rank among his 60s stuff. And as the snapshot comparisons throughout reveal, Dylan seems to have aged somehow ambiguously since then:

He comes off even younger in his Letterman performance of "Jokerman," which Dylanites now seem to regard as a sacred event. In it he pushes the song almost unrecognizably into the aesthetic territory of new wave, even wearing a skinny tie for the occasion:

The trends of the 80s did seem to exert a stronger influence on big 60s acts than did the trends of the 70s, but I wouldn't be surprised if Dylan never fully got on board with any of them. Hence his not getting called a "chameleon" as often as, say, David Bowie.

Bowie, in fact, was among the candidates for producer of Infidels, though Dylan ultimately went with Mark Knopfler — who brings more the sound you want when you're recording, say, a cri de coeur about the weakening of unions through labor offshoring.

Empire Burlesque: Last week I wrote of my suspicions that Dylan wouldn't buy all the way in to the sounds of the 80s, but a Dylanite would surely expect this album to make me eat my words. And sure, I admit that anyone could place most of its tracks to the year upon first listen.

Though an "80s album" in every sense, it's not quite as much of one as, say, the Beach Boys' release also of 1985. But the latter brought on the producer from Culture Club, so it's fair to say they got the sound they paid for, whereas Dylan self-produced.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1314370285617901569

From what I've read, Dylan presented himself during the making of the album as a plain old singer-songwriter who knew nothing of pop music and its trends — who somehow ended up in a lead-single music video shot in Tokyo and directed by Paul Schrader.

Despite my ignorance of nearly all things Dylan before I started listening through his discography, I can't believe I hadn't already heard of that video long ago. It even features Baisho Mitsuko, whom if you're like me you know well indeed from Imamura Shōhei's Vengeance Is Mine.

The track most heavily saturated with 80s-style electronics, "When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky," comes quite late, but was also released as a video single. It's the drums — not so much their regularity as their tone — doing the heavy 80s lifting.

This dated sound, I gather, makes Empire Burlesque one of the most Dylanite-divisive albums. Personally, I always go in for clashes between the nature of the artist and the style of the production: see the aforementioned Beach Boys album, or even the Rolling Stones' Dirty Work.

Admittedly, Dylan was a figure flamboyantly unsuited to the 80s. A faint air of ridiculousness hangs around most of these songs, as it does around the man himself as he roams bubble-era Tokyo. In any case, expect further exploration of this topic when I do a Leonard Cohen thread.

Knocked Out Loaded: We're now in a widely acknowledged slump, though one far from the legendary "badness" of Self Portrait, which a contrarian Dylanite could well pick as his favorite album. But it would take a perverse Dylanite indeed to pick one as diffuse as this.

Still, like many a Dylan album remembered as not particularly consequential, it contains one song now regarded as its justification: in this case "Brownsville Girl," an eleven-minute piece of dusty women-and-lawmen Americana co-written with Sam Shepard:

More of an oddity is "They Killed Him," a song originally written by Kris Kristofferson about Gandhi, MLK, JFK, RFK, and Jesus. Unlike Kristofferson (but like Johnny Cash, who also recorded it), Dylan employs a children's chorus to sing of their martyrdom.

My favorite track ended up being "Driftin' Too Far from Shore," though I acknowledge that in most objective and semi-objective respects it's probably the worst of the bunch. What can I say? That box-of-bees synthesizer does it for me:

In my defense, that song is one of only two compositions on Knocked Out Loaded credited to Dylan alone. Other collaborators include Tom Petty and Carole Bayer Sager, not that they lend much coherence; ultimately, it all feels a bit like a Self Portrait-style "official bootleg."

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: In 1987, Bob Dylan appeared in Richard Marquand's Hearts of Fire as a has-been rocker named Billy Parker. The story puts him in a kind of rivalry with Rupert Everett's mulleted British pop star, whose hit is a version of "Tainted Love" much like Soft Cell's.

Insofar as the two men two fight, they do so over a woman: here rising teenage singer-songwriter Molly McGuire, played by rising non-teenage singer-songwriter Fiona Flanagan, billed mononymously as Fiona. Everett's character eventually beds her; Dylan's never seems interested.

Hearts of Fire is remembered, if at all, as a bad movie, and that assessment does indeed hit the mark. Its straight-to-video look and feel is one thing, but it also makes frequent bids for conventional impact that nearly all miss their mark; something about the editing is "off."

Of course, nobody's going to watch this for any other reason than Bob Dylan, who despite having been criticized as a sleepwalker in front of the camera ends up being the most compelling presence in the movie. As you'd expect, he appears to be taking hardly any of it seriously.

Whatever its flaws, Renaldo and Clara makes sense as Dylan's own (in its way an ambitious) project. But from today's perspective, why he signed on to a piece of 80s kitsch like Hearts of Fire is harder to understand but for his music's being at a low critical and commercial ebb.

Encounters between a man on the way down and a woman on the way up continue to be the stuff of drama (or more often melodrama) today. What's ironic in this case is that Fiona remains best known for having once acted opposite Dylan, who would make an acclaimed comeback in the 90s.

You could view Molly/Fiona as a creature purpose-built for the 80s, whereas Billy/Dylan exudes obvious discomfort with the nature of the times (right down to his own wardrobe). Billy is a Dylan who gave in and played the hits, then went into bitter retirement as a chicken farmer.

There's probably more for the Dylanite here than the Dylanite expects. You've got obvious visual references to his career (the marquee featuring Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, etc.), but also more indirect allusions to the kind of fame Dylan then enjoyed — if enjoyed be the word.

Notably, the film gives Dylan a line about not being one of those rock stars who wins Nobel Prizes, which now sounds ironically prophetic. Even more notably, it includes him punching like this:

https://twitter.com/i/status/1264582647575019521

Down in the Groove: After Self Portrait, this is most often called Dylan's worst album. Though it certainly hasn't done much to distinguish itself through the listens I've given it this past week, I doubt any given track heard in isolation would sound like "worst album" material.

Like Knocked Out Loaded, there are a lot of covers, a few collaborations, and a couple of originals. One of the originals Dylan performs with Full Force, of all groups, though it could be anybody; one of the collaborations he plays with the Grateful Dead:

Even beyond that, the roster is impressive: Eric Clapton, Nathan East, Mark Knopfler, Ronnie Wood (presumably fresh from his cameo in Hearts of Fire). But for critics their efforts seem to amount to precious little. Maybe the problem was too many sessions, over too long a period.

As we approach to the end of Dylan's last major slump, here's a general observation about 60s-forged acts in the 80s: those who survived intact toured with surprising vigor, but each tour required a fresh round of "product" to sell. Albums like Down in the Groove were the result.

Oh Mercy: I'd anticipated this one since reading that it marked yet another Return to Form after Dylan's mostly lackluster 1980s — and because it was produced by Daniel Lanois, whose close association with Brian Eno makes this the closest thing yet to an Eno-overseen Dylan album.

It hasn't disappointed me. Some of the strength of Oh Mercy owes to its having been recorded in a relatively short span of time, and in a single studio; some of it owes to Lanois having incorporated that studio's location, deep in residential New Orleans, into its overall sound.

Lanois has spoken about how he and Dylan did all their recording late at night, with an eye — or rather an ear — toward making songs that sound like they're coming in over the radio even later at night. "Man in the Long Black Coat" is a standout example:

That one incorporates actual recordings of the crickets that came out at night in the studio's neighborhood. But similarly shimmering insectoid sounds also underlie other tracks, constituting just one part of what I hesitate to call the album's soundscape.

Whatever my reservations about the term, a soundscape is what I've sensed lacking in many previous Dylan albums. The 80s in general and Lanois in particular have been subject to charges of overproduction, but would it be too much to call underproduction a weakness of Dylan's?

Under the Red Sky: Another case of an interesting, focused Dylan album followed by a less interesting, less focused one. That's more or less the critical consensus, although I did notice my own lack of eagerness to listen to this one each day relative to how it was with Oh Mercy.

Upon first listen, I didn't even sense the parade of high-profile cameos: Slash, Elton John, David Crosby, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Bruce Hornsby, George Harrison. (Speaking of Harrison, Dylan's busyness with the Traveling Wilburys is one factor blamed for the album's shortcomings.)

At this point in Dylan's oeuvre I find myself especially interested in the producers he works with. On this album it's Don Was, a big name (especially at the time) on whose sensibility I have yet to get a grip, though he did pretty well by the Stones.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1380363867369340928

I suspect I could get into the music of Was (Not Was), despite having heard almost none of it. Maybe it has to do with their heyday's having come in the late 80s and early 90s, a cultural period that fascinates me with its union of self-amusing irony and glossy blandness.

Under the Red Sky is unmistakably a product of that period, not just its highly professional yet lackadaisical attitude but occasionally in its subject matter as well. One of its songs is about the derangement caused by an excess of television news:

Good as I Been to You: After a relative disappointment shall come an album that goes Back to Basics. And Dylan goes quite far back indeed for this one, on which — aided only by his own guitar and harmonica — he sings and plays almost nothing traditional folk and blues numbers.

That strikes me as a pretty bold concept for 1992, especially when executed at a length of 55 minutes. (But then, that was probably the shortest many listeners would accept at the time, back when the dominance of the CD saw album runtimes pushing ever closer to 80 minutes.)

It appeals to my sense of incongruity to head Dylan sing "Blackjack Davey," a song narrated in part by a fifteen-year-old-girl who (after removing her shoes "all made of Spanish leather") leaves her husband and baby for the gypsy rogue of the title:

At this point Dylan has never sounded less like a fifteen-year-old girl. Contemporary reviewers were noticing the toll decades of singing (and everything else he'd been up to) had taken on the then-quinquagenarian Dylan's voice, well though it serves this particular material.

In fact, I could imagine Dylan's music only getting better the more ravaged he sounds. He may be one of those artists never really "meant" to be young — an anomaly in the realm of late 20th century popular music, but such anomalousness long seems to have been his stock-in-trade.

The longest song is the last and by far the silliest. "Froggie Went a Courtin'" did not appear on Peggy Seeger's Animal Folk Songs for Children, which I once asked for on inexplicable impulse when I was a kid in the early 90s myself, but it should have:

World Gone Wrong: This one is even more stripped-down and backward-looking than its predecessor, which is hardly what the cover design would lead one to expect. Though often unremarkable, Dylan's covers do occasionally exude the aesthetic of the age, in this case the year 1993.

The high-contrast, saturated-color photo of a top-hatted Dylan raises suspicions that he's put a foot in the "alternative" or even Goth realms. It seems to come from the shoot of the album's only video, which also keeps with the style of the day, visually:

Roaming the streets of London, signing a few autographs and accruing a listless group of followers, Dylan looks anachronistic in a different way than usual. It's not easy to imagine a video like this making a go of it on MTV, though perhaps it could've got traction on VH1.

Nor is it easy to imagine World Gone Wrong winning the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album in 1993 — not because it's bad, but because the very idea of a Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album in 1993 makes the mind reel. Who else could possibly have been contending, I wonder?

The major Dylans include Dylan the songwriter and Dylan the interpreter, and World Gone Wrong obviously belongs to the latter. But as this @YoZushi81 piece has it, in the eyes both of them and indeed all other Dylans, the world has always been going wrong: newhumanist.org.uk/articles/5111/…

Time Out of Mind: As I suspected, this album has nothing to do with the Steely Dan song of the same name. Yet it does strike me as one of the Dylan albums Steely Dan fans would most appreciate, not least because of its relatively painstaking production and many-layered sound.

That sound does not, however, sustain a Steely Dan-like pristine-ness all the way through, which Dylan fans will appreciate. Some songs are deliberately made to sound "bad," such as the second track with its basic riff taken straight from an old cassette:

I'd been looking forward to hearing the production, handled as it is by Daniel Lanois in his second collaboration with Dylan. The first was Oh Mercy, eight years before, and this album plays like a both more expansive and more ragged version of that one.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1451427519161257989

Compared to Oh Mercy, Time Out of Mind does lack a sense of place — that is, a place more specific than "Bob Dylan's America." The earlier album was recorded in New Orleans, and you could feel it; this one was recorded in Miami, but I can't sense that city coming through at all.

It's nevertheless been quite highly regarded by some, though charged with overproduction by others. It does exude a sense of all-around excess, in everything from the two separate bands used in the studio it to the 73-minute runtime that dates it to the 1990s peak-CD era.

In keeping with that sensibility, the album's "Desolation Row"-style closer is five minutes longer than "Desolation Row": the longest song, in fact, that Dylan had recorded to date. Inspired by Robert Burns, it also, weirdly, makes reference to Erica Jong:

Love and Theft: This album happened to come out on 9/11, which perhaps suits Dylan's instinct for inhabiting American history. So, in a more typical manner, does the material itself, which showcases his frequently-described-as-encyclopedic knowledge of old American musical forms.

The title Love and Theft comes from a historical study of blackface minstrelsy published a few years before. One thus expects a seriously antiquarian, maybe even arid listening experience, as if the arrival of the 21st century threw Dylan into full-on contrarian Alan Lomax mode.

Most of the music on the album does sound "old" in a stylistic sense, yet also as new as anything recorded over the past couple of decades in a technical one. Love and Theft could only have been recorded in the early 21st century — and only by an artist rooted in the early 20th.

The mélange on offer includes the blues, Western swing, Tin Pan Alley, and jazz — a welcome source, about 40 years into Dylan's recording career, of additional rhythmic and harmonic complexity. "Po' Boy" is a good example of how these currents converge:

Love and Theft is all-original, but one could pay it few higher compliments than saying its songs feel like covers. That is, they feel like they must have existed long before these recordings, as Dylan has described the genres that inspired them having existed long before he did.

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: Masked and Anonymous took a critical drubbing upon its release, but the negative reviews exuded enough middlebrow frustration to encourage my own suspicions, harbored over the past 18 years, that the movie was Actually Good — or at least actually something.

I'd gathered that Dylan plays a Dylan-like (but non-Dylan) singer who wanders around a war-torn dictatorship that may or may not be the United States, mumbling cryptic pronouncements. And so he does, although this also happens to be a Los Angeles movie, and thus in my wheelhouse.

A practically unaltered Skid Row, shot out the window of a moving car, does much of the heavy lifting to establish this blasted and desperate setting. I was reminded of near-identical images in Wim Wenders' relatively straight-ahead Land of Plenty, which came out two years later.

In sensibility, Masked and Anonymous strikes me as more similar to Wenders' earlier Los Angeles movie The Million Dollar Hotel. In fact the two seem almost to occupy proximate cinematic realities, alongside that of Richard Kelly's Southland Tales. vimeo.com/119834541

Like Southland Tales, Masked and Anonymous plays as if based on a larger body of too-drastically excised world-building, and if it does indeed have a political message to transmit, that message seems to have been garbed at conception by Bush Derangement Syndrome.

And though dismissed as a piece of incoherent art-house pretension, this movie also has much in common with Dylan's previous starring vehicle Hearts of Fire, which was dismissed (not wrongly) as an inconsequential 1980s pop-music-driven quasi-romance.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1448704868286283780

Both Hearts of Fire's Billy Parker and Masked and Anonymous' Jack Fate are once-famous singer-songwriters who haven't been heard from in years. Each is convinced to re-emerge and provide equanimous commentary the frantic doings around him. Each resorts, in the end, to violence.

Both insist that they don't have the answers to anyone's questions — nor do their songs, and nor, certainly, does any movie. This seems in keeping with Dylan's outlook as a songwriter, but many in the generation that most reveres his work couldn't handle its cinematic equivalent.

Modern Times: A local critical and commercial peak for "late Dylan." When it came out in 2006, even I knew about it, though my reaction was along the lines of, "Huh. So Bob Dylan is still putting out albums!" (I'd thought the same about the Stones' a Bigger Bang the year before.)

It actually hit number one on the Billboard charts, making Dylan the oldest living artist to have recorded such an album. That strikes me as a telling record, on the matters of both the nature of the Dylan phenomenon and the changes the music industry was undergoing even then.

The music itself is also laid-back, much more thoroughly so than I'd expect from the songs on a hit. On that level it reminds me of the Stones' Exile on Main St., another highly celebrated album on which I've found it difficult to quite get a grip.

https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1352434788452327424

Dylan's obsession with antiquarian Americana is still driving things, creating the context for such notable incongruities as a reference to Alicia Keys about 40 seconds into the opener (already more dated than his mention of Erica Jong a few albums ago):

In the middle comes another tribute to the working man, this one a follow-up to a Merle Haggard song harmonically based on Pachelbel's Canon — but what I somehow kept thinking of was "Union Sundown," a thematically similar throwaway track back on Infidels.

Dylan's lyrical appropriation of the words of Henry Timrod, "poet laureate of the Confederacy," has been well noted. What's less clear is whether Timrod counts as more or less likely a source than Junichi Saga, whose Confessions of a Yakuza was a notable source on Love and Theft.

Together Through Life: At this point Dylan's voice has roughened enough to resemble Tom Waits'. You wouldn't confuse one for the other, but both are equally suited to singing about an American not-quite-low life lived in less-than-clean diners and on pre-Interstate roads.

In these songs are American boulevards of broken cars, American wives from hell, American Houstons, American Saturday night specials, American nowhere cafés, American Billy Joe Shavers. The closing number alone has dirt, dust, lying politicians, cold-blooded killers and cop cars.

I'm drawn to such visions of America, as anyone who listens to Bob Dylan would be — or for that matter, any American living abroad, and in a time sufficiently far from those such visions recall. (It can't be incidental that the album's Bruce Davidson cover photo is from 1959.)

Dylanites seem to consider Together Through Life quite a departure from its immediate predecessors, though I admit that it pretty much sounds of a piece to me with both Love and Theft and Modern Times. It strikes me as like those laid-back, backward-looking albums, but more so.

This gets me wondering how far Dylan can go/went down this road. After all, I've got six more of his albums to go. I note that this one was up for a Best Americana Grammy (an award introduced that same year), but nothing he's done since has been. I thus sense changes a-comin'.

Christmas in the Heart: Normally I would skip over a Christmas album, but since it happens to be mid-December, this one could hardly have come at a more appropriate time. And besides, the very idea that Bob Dylan made a Christmas album at all appeals to my sense of incongruity.

Though regarded as a great oddity of 21st-century music, it makes a kind of sense. Dylan has always been an interpreter of American music, from the traditional to the pre-war, and though originally Jewish, he never did repudiate the Christianity to which he converted in the 70s.

And so it's not without credibility that he performs a Christmas song like this album's opener "Here Comes Santa Claus," complete with the lines about us all being God's children and peace on Earth being possible if we just "follow the light":

And he sings it — as well as all the other Christmas standards here — in a voice by now comically ragged. This grants a certain novelty value to these recordings, all of which are far better and more interestingly arranged than the average Christmas album (a low bar, but still).

Most of Dylan's selections come from the mid-1930s to the early 60s, a golden age of Christmas songs coeval with the golden age of radio. Here and there he reaches further back for the likes of "Hark the Herald Angels Sing" and "O Come, All Ye Faithful" in both English and Latin.

Among the newer and less familiar songs is "Must Be Santa," which has its roots in the German beer-hall song and in this version includes the phrase "Carter, Reagan, Bush, and Clinton." When asked what America is like, I'll just pull up its music video:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh